eISSN: 2576-4497

Research Article Volume 1 Issue 4

Department of Intensive Care, Institute of Oncology and Radiobiology, Cuba

Correspondence: Frank Daniel Martos Benitez, Department of Intensive Care, Institute of Oncology and Radiobiology, Fuentes street No. 367A, Guanabacoa, Havana, Cuba , Tel +53 53925706

Received: August 28, 2017 | Published: September 26, 2017

Citation: Benítez FDM, García AS, Noyola AG, et al. Disability and quality of life after surgery for cancer. Hos Pal Med Int Jnl. 2017;1(4):76–82. DOI: 10.15406/hpmij.2017.01.00020

Purpose: We aimed to assess the prevalence of disability and health-related quality of life (HRQoL), as well as associated risk factors among patients operated for gastrointestinal or thoracic cancer.

Methods: A retrospective study was performed on 97 survivor patients underwent curative surgery for gastrointestinal or thoracic cancer. Subjects were contacted by phone call between 6-12 months after surgery. Completely dependent patients in any item of modified Katz index were defined as disabled. Severe impairment in HRQoL was defined as ≤50 points in the EuroQoL-5D-3L-visual analogue scale.

Results: The median age of 63.0 years (IQR 56.0-71.0years). Gastrointestinal and thoracic surgery was performed in 67(69.1%) and 30 patients(30.9%), respectively. Thirty-eight(39.2%) participants develop a postoperative major complication. The disability and severe impairment in HRQoL prevalence was 17.5% and 19.5%, respectively. Advanced cancer (52.9% vs. 25.0%; p= 0.046), ASA class≥3 (52.9% vs. 22.5%; p=0.030) and postoperative major complications (58.8% vs. 23.8%; p=0.010), while advanced cancer (52.6% vs. 24.4%; p=0.033), postoperative major complications (63.2% vs. 25.6%; p=0.004) and disability (73.7% vs. 24.4%; p=0.0001) were the risk factor for severe impairment in HRQoL.

Conclusions: Disability and severe impairment in HRQoL are uncommon in patients operated for thoracic or gastrointestinal cancer. However, some risk factors such as advanced cancer, ASA class≥3 and postoperative major complications could aid in establishing a directed rehabilitation program for preventing disability and improve HRQoL in this population.

Keywords: cancer, surgery, quality of life, activities of daily living, disability, postoperative complications

HRQoL: Health Related Quality of Life; ADL: Activities of Daily Living; QoL: Quality of Life; IOR: Institute of Oncology and Radiobiology; ACCI: Adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index; ASA: American Society of Anaesthesiology; APCHE: Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; VAS: Visual Analogue Scale; IQR: Interquartile Range; PS: Performance Status

Cancer is one of first cause of death around the world and Cuba.1 Surgery is one of most important therapeutic tool for its control, either for curative or palliative purpose. Although surgical intervention can be a life-saviour strategy for these patients, several complications could be present in postoperative period,2 as well as limitations for activities of daily living (ADL) and derangement in quality of life (QoL).3 Postoperative recovery is a dynamic process where biological, physiological, functional and psychological components play a pivotal role. A rise in physical independence and gradual return to ADL are global indicator of functional recovery after surgery. For most patients, the evaluation of ADL is only performed during their hospital stay. Traditionally, patients should probe their capacity to walking, eating, bathing and dressing without help.1

Elderly patients are a special increasing subgroup.5 Because of the ageing-related characteristics, this population has a decreased functional capacity even before hospital admission.6 According to literature reports, more than 10% of elderly patients develop a severe postoperative disability. 7Postoperative evaluations of functional capacity and health-related QoL (HRQoL) have been become as an important component of long-term surgical outcomes, particularly in the elderly population.8-11

The problem is more serious in the case of cancer patients because a higher prevalence of malignancies among the elderly subgroup.12,13 Frequently, surgical indication for elderly patients with comorbidities is based on subjective judgement according to the personal experience of surgeon. In addition, a negative attitude regarding elderly patients can be see among some physicians, which lead to patients with acceptable functional status could be not surgically treated as usually is indicated for younger patients. Furthermore, radical surgical interventions are neither performed in elderly population. This is significant because currently the primary tumour and regional lymphatic node can only be removed by radical intervention with surgical margin, which guarantees a higher probability of cure.14,15 This study was aimed to assess the prevalence of disability and health-related quality of life, as well as related risk factors among patients operated for gastrointestinal or thoracic cancer.

Design and setting

This retrospective study was conducted in the oncological ICU (OICU) of the Institute of Oncology and Radiobiology (IOR). This is a 220-bed, university-affiliated, tertiary care referral centre for cancer patients in Havana, Cuba. The OICU has 12 beds and provides care for about 400 surgical cancer patients per year. The current study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and it was approved by the Scientific Council and the Ethics Committee for Scientific Research of the IOR (September 2014).

Participants

Using the prospective database of the OICU, patients underwent thoracic (lung, mediastinum) or gastrointestinal (oesophagus, stomach, small intestine, pancreas, liver, biliary, colon or rectum) curative surgery for cancer were selected from July 2013 to July 2014. Of these patients, those operated six to 12 month before, discharged alive from the hospital, and with residence in Havana were included (Figure 1).

Telephone numbers were searched in hospital records and all included subjects were called (November 2014-February 2015). The following patients were excluded:

Data collection and outcomes

The following variables on OICU admission were extracted from the medical records: age, sex, Age-Adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index (ACCI), cancer stage, surgical location, emergency surgery, American Society of Anaesthesiology (ASA) class, intraoperative complication, surgical time, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score, postoperative major complications (unplanned re-intervention and/or organ dysfunction),16 and length of OICU and hospital stay.

A modified Katz index scale was applied to measure the ADL in our study, which included the following six items: dressing, feeding, transferring (getting in/out of bed), walking (walking around inside), bathing, and toileting. Each item had three response choices: “completely independent”, “needing some help”, and “completely dependent”. If any answer was “completely dependent”, participants were defined as disabled; otherwise the participants were categorized as nondisabled.17

HRQoL were assessed using the EuroQoL-5D-3L, which is a brief self-reported generic measure of current health that consists of five dimensions (Mobility, Self-Care, Usual Activities, Pain/Discomfort, and Anxiety/Depression), each with three levels of functioning (no problems, some problems, and unable to/extreme problems). In addition, the EuroQoL-5D-3L includes a visual analogue scale (VAS) where own health ‘‘today’’ is rated on a scale from 0 (worst imaginable health) to 100 (best imaginable health). Severe impairment in HRQoL was defined as ≤50 points in VAS. Both the modified Katz index3,17-21 and EuroQoL-5D-3L22-30 has been widely used in different clinical setting, including surgical cancer patients.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are shown as count with percentage, whereas continuous variables are represented as median with 25th-75th interquartile range (IQR). Between-group comparisons were performed using the chi-square (χ2) test or Fisher’s exact test based on which test was more suitable for qualitative variables. Because of lack of normality, the Mann-Whitney U test was used for numerical variables. Statistical test with a two tailed p-value ≤0.05 was considered as significant. Data were analysed using IBMâ SPSSâ Statistics 23.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA).

Characteristics of study population

Ninety-seven patients were analysed with a median age of 63.0 years (IQR 56.0-71.0years). Comorbidities were measured by the ACCI score (median 3.0 points (IQR 2.0-5.0 points); a score ≥2 points was observed in 86.6% of subjects. Gastrointestinal and thoracic surgery was performed in 67(69.1%) and 30 patients (30.9%), respectively. The most common gastrointestinal surgery was colorectal (55.2%), whereas pulmonary resection (73.3%) was the predominant thoracic surgery. The emergency surgery was carried out in 8.2% of patients. Intraoperative complications were observed in 5.2% (Table 1). The median APACHE II score was 10.0 points (IQR 8.0-12.0 points) with 11.1% (RIQ 8.1-14.6%) as median estimated probability of death. The median time of OICU stay after surgery and overall time of hospitalization was 3.0 days (IQR 2.0-5.0 days) and 8.0 days (IQR 7.0-11.0 days), respectively. Because of the curative intention of the surgery, all patients received oncological therapy after surgery such as chemotherapy (52,6%), radiotherapy (30,9%) or both (16,5%).

Characteristic |

N= 97 |

Age, Years (IQR) |

63 (56-71) |

≥ 60 years, n (%) |

61 (62.9) |

≥ 80 years, n (%) |

4 (4.1) |

Gender, n (%) |

|

Male |

40 (41.2) |

Female |

57 (58.8) |

Age-Adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index, Points (IQR) |

3 (2-5) |

Advanced cancer (stage IIIb-IV), n (%) |

28 (28,9) |

ASA class ≥3, n (%) |

39 (40.2) |

Surgical Location, n (%) |

|

Gastrointestinal surgery |

67 (69.1) |

Oesophagus |

20 (29.9) |

Stomach |

4 (13.3) |

Colorectal |

37 (55.2) |

Hepato-bilily-pancreatic |

3 (4.5) |

Others |

7 (10.4) |

Thoracic surgery |

30 (30.9) |

Pulmonary resection |

22 (73.3) |

Mediastinum |

4 (13.3) |

Emergency Surgery, n (%) |

8 (8.2) |

Intraoperative Complications, n (%) |

5 (5.2) |

Surgical Time, Minutes (IQR) |

234 (196-305) |

APACHE II Score, Points (IQR) |

10 (8-12) |

Length of OICU Stay, Days (IQR) |

3.0 (2.0-5.0) |

Length of Hospital Stay, Days (IQR) |

8.0 (7.0-11.0) |

Table 1 General characteristics of participants

APACHE: Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; ASA: American Society of Anaesthesiology; IQR: Interquartile Ranges

Postoperative complications

At least one postoperative major complication occurred across 38 participants (39.2%). Medical and surgical postoperative complications were found in 31(32.0%) and 15(15.5%) patients, respectively. Eight subjects (8.2%) developed both medical and surgical complications. A total of 45 complications were diagnosed. Of these, the most common complications were delirium (22.2%) and pneumonia (22.2%), followed by atelectasis (13.3%) and anastomotic leak (13.3%). Other postoperative complications were surgical wound infection, postoperative haemorrhage, acute heart failure, intestinal perforation/ obstruction, persistent air-pulmonary leak and broncopleural fistula (Figure 2). Infectious complications were found in 20 patients (44.4%) and four (8.9%) develop septic shock.

Medical postoperative complications were significantly more frequent than surgical postoperative complications (68.9% vs. 31.1%; p< 0.0001). Compared with patients underwent thoracic surgery, those experienced gastrointestinal surgery had a higher complications rate (56.7% vs. 31.3%; p= 0.033). The overall median length of OICU and hospital stay was 3.0 days (IQR 2.0-5.0 days) and 9.0 days (IQR 7.0- 14.0 days), respectively. Thoracic and gastrointestinal surgical patients had a median length of hospital stay of 8.0 days (IQR 6.8-12.3 days) and 10.0 days (IQR 8.0-15.0 days), respectively. Furthermore, a significant statistically difference was not observed between groups (p=0,214).

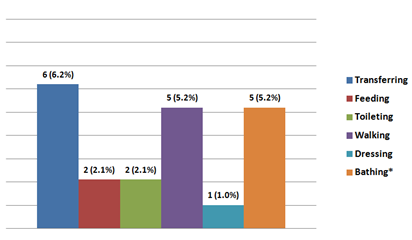

Assessment of disability

The overall disability prevalence was 17.5%. The prevalence of disability was highest for “transferring” (6.2%), followed by “walking” (5.2%) and “bathing” (5.2%) (Figure 3). There was no difference between patients underwent gastrointestinal surgery and those experienced thoracic surgery regarding disability prevalence (68.8% vs. 70.6%; p=1.000). Advanced cancer (52.9% vs. 25.0%; p= 0.046), ASA class ≥3 (52.9% vs. 22.5%; p=0.030) and postoperative major complications (58.8% vs. 23.8%; p=0.010) rates were significantly higher in patients with disability than those observed in patients without disability (Table 2).

Figure 3 Activities of daily living according to modified Katz index.

*: A same patient could have more than one limitation.

Characteristic |

Disabled N = 17 |

Nondisabled N = 80 |

p |

Age, years (IQR) |

63.4 (54.2-72,6) |

61.6 (52.0-71.2) |

0.407 |

Gender (male), n (%) |

8 (47.1) |

35 (43.8) |

0.985 |

Advanced Cancer (stage IIIb-IV), n (%) |

9 (52.9) |

20 (25.0) |

0.046 |

ASA class ≥3, n (%) |

9 (52.9) |

18 (22.5) |

0.03 |

Surgical Location, n (%) |

|

|

0.855 |

Gastrointestinal Surgery |

10 (58.8) |

48 (60.0) |

|

Thoracic Surgery |

7 (41.2) |

32 (40.0) |

|

Emergency Surgery, n (%) |

2 (11.8) |

5 (6.3) |

0.71 |

Intraoperative Complications, n (%) |

5 (29.4) |

16 (20.0) |

0.576 |

Surgical Time, Minutes (IQR) |

229 (191-299) |

225 (189-297) |

0.681 |

APACHE II Score, Points (IQR) |

11 (8-13) |

10 (8-12) |

1 |

Postoperative Major Complication, n(%) |

10 (58.8) |

19 (23.8) |

0.01 |

Table 2 Factors associated with limitations for activities of daily living

ADL: activities of daily living; IQR: Interquartile Ranges

Health-related quality of life

The most affected dimension in the EuroQoL-5D-3L was “mobility” (51.5% with some or extreme problems), followed by “pain/ discomfort” (45.4% with some or extreme problems) and “anxiety/ depression” (39.2% with some or extreme problems). However, dimension “usual activities” showed the highest rate of extreme problems. The lowest affected dimension was “self-care” because 72.2% of patients had not problems (Table 3). The median VAS was 73 points (IQR 58.0-81.0 points). A VAS less than or equal to 50 and 25 points was found in 19.6% and 10.3% of patients, respectively. There was no statistical difference regarding VAS between gastrointestinal surgical patients and those underwent thoracic surgery (median 73.5 points [IQR 63.3-78.8 points] vs. median 73.0 points [IQR 56.0-81.0 points]; p=0.913). Factors associated with severe impairment in health-related quality of life were advanced cancer (52.6% vs. 24.4%; p=0.033), postoperative major complications (63.2% vs. 25.6%; p=0.004) and disability (73.7% vs. 24.4%; p=0.0001) (Table 4).

Dimension |

Level |

||

No Problems |

Some Problems |

Extreme Problems |

|

Mobility |

47(48.5) |

39(40.2) |

11(11.3) |

Self-care |

70(72.2) |

17(17.5) |

10(10.3) |

Usual Activities |

57(58.8) |

21(21.6) |

19(19.6) |

Pain/Discomfort |

53(54.6) |

34(35.1) |

10(10.3) |

Anxiety/Depression |

59(60.8) |

26(26.8) |

12(12.4) |

Table 3 Health-related quality of life according to the EuroQoL-5D-3L

Characteristic |

Severe Impairment |

No Severe Impairment |

p |

Age, years (IQR) |

64.2(55.2-73.5) |

62.3(52.5-70.1) |

0.53 |

Gender (male), n (%) |

9(47.4) |

34(43.6) |

0.968 |

Advanced Cancer |

10(52.6) |

19(24.4) |

0.033 |

ASA class ≥3, n (%) |

9(47.4) |

19(24.4) |

0.09 |

Surgical Location, n (%) |

|

|

0.808 |

Gastrointestinal Surgery |

11(57.9) |

45(57.7) |

|

Thoracic Surgery |

8(42.1) |

33(42.3) |

|

Emergency Surgery, n (%) |

3(15.8) |

5(6.4) |

0.373 |

Intraoperative |

9(47.4) |

18(23.1) |

0.067 |

Surgical Time, |

233(190-301) |

226(190-299) |

0.467 |

APACHE II Score, |

12(9-14) |

11(8-13) |

0.054 |

Postoperative Major |

12(63.2) |

20(25.6) |

0.004 |

Disability, n(%) |

14(73.7) |

19(24.4) |

0.0001 |

Table 4 Factors associated with impairment in health-related quality of life

IQR, interquartile ranges; QoL, quality of life

The health status before surgery, as well as postoperative complications can affect the well-being of patients undergoing surgical intervention for cancer at short, medium and long term. Thus medical, social, and functional points of view are important to anticipate the expected postoperative functional status and care needs prior to surgery, and to inform patients and their families.

Disability is a frequently observed condition at hospital discharge with a prevalence of almost 30%.31 Additionally, changes in the functional status of the cancer patients are common, which could affect the prognosis; consequently, applying the assessment tools is important to assist clinical oncologist. Thus disability has been assessed in several studies of cancer patients.3,8 Recently, Khoei et al.32 proved that the Katz index is a reliable instrument for oncologic patients using the Physical Function subscale of SF 36 as criterion of validity (Cronbach’s alpha 0.923).32

Elderly patients were the most frequent population in our study. This is not surprising because the elderly population is at higher risk of cancer.33 It is well established that declines in physical function are an inevitable part of the aging process and are markers of disability risk.6 Once the elderly become disabled, their physical health declines along with their mental health, their quality of life deteriorates rapidly and they require long-term care.34 A multicentre prospective study of 639 institutionalized elderly patients with and without cancer showed a disability prevalence of 33%.35 This study showed that 17.5% of patients experienced disability after abdominal or thoracic surgery for cancer. Furthermore, advanced cancer, ASA class ≥3 and postoperative major complications were the risk factors associated with disability.

Although the functional status such as ADL and QoL are important for outcomes assessment in postoperative cancer patients, there have been only a limited number of reports on the natural course of recovery of functional independence. In patients operated for gastric or colorectal cancer, Amemiya et al.3 observed a disability rate of 24%. The surgical risk predictive scales such as POSSUM and E-PASS were the associated risk factors.3 We observed a disability rate of 17%. These differences with our results appear to derive from differences in the composition of the studied participants. For example, in our study only postoperative patients were included.

In patients receiving lobectomy for non-small cell lung cancer, Kawaguchi et al. observed an incidence of 18.2% for the decline in postoperative performance status (PS), assessed by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group PS. Risk factors for decreasing PS after surgery were history of cardiac ischemia (p=0.001) and squamous cell carcinoma (p=0.015). Authors also found a higher overall 5-year survival rate for patients with postoperative PS < preoperative PS than those for patients with postoperative PS=reoperative PS.36

Saraiva et al.37 found that a better functional status, based on METs, was associated with reduced odds of postoperative complications in multivariate analysis (odds ratio 0.11; 95% CI 0.02-0.85; p= 0.034).37 Conversely, we observed that postoperative major complications were a risk factor for limitations in ADL. Thus the relationship between postoperative complications and physical performance is a dynamic process with two-way effects. Hence, impairment in physical performance and limitations for basic ADL are important risk factors for subsequent disability and erosion of independent living, institutionalization, compromised quality of life and death, especially in older people operated for cancer. The need to develop practical and accessible approaches for the prevention of decline in functional performance can be considered a key public health priority.

Almost 20% of patients experienced a severe impairment in HRQoL in our study. Additionally, advanced cancer, postoperative major complications and disability were the associated risk factors. Regarding HRQoL, in patients operated for gastric cancer, Lim et al.11 observed that postoperative nutritional status has a negative effect on HRQoL, especially regarding global health, physical functions, fatigue, pain, appetite, reflux and anxiety. Consequently, a nutritional intervention for patients undergoing upper gastrointestinal tract surgery for cancer is mandatory, particularly for malnourished patients or at risk.

Brown et al. studied the effects of postoperative complications on HRQoL of 614 patients underwent colorectal surgery for cancer. The postoperative complication rate was 35%. The most common dimensions affected in HRQoL were mobility, self-care and pain/discomfort.8 These results coincide with our find; thus postoperative complications should be taken into account to assess the HRQoL after surgery. Postoperative complications are associated with an ADL declined.3 We found that disability was related with impairment in HRQoL. Consequently, postoperative complications, through the limitations for ADL, could explain its negative effect on HRQoL.

Physical activity interventions and the incorporation of physical activity into a healthy lifestyle represent at least one behavioural modality for possibly attenuating the effects of the surgical damage on functional limitations and disability and the attendant declines in quality of life.38 One potential way to understand the relationship between physical activity, functional limitations and QoL may be through the pathways of self-efficacy and physical function performance. That is, more active individuals are likely to be more efficacious, which should lead to better physical functional performance, fewer limitations and better well-being.

Several systematic reviews on surgical cancer patient have demonstrated the effectiveness of preoperative exercise training on HRQoL.39-41 Two recent systematic reviews in people with cancer undergoing adjuvant or neoadjuvant cancer treatment and surgery demonstrated that exercise training is safe and feasible and improves the physical fitness and HRQoL.42,43 Strengths of this study include that the evaluation of disability and HRQoL were performed by previously used methods for postoperative cancer patients such as modified Katz index and EuroQoL-5D-3L, respectively.3,8 The present study has several shortcomings. First, ADL and HRQoL were not compared before and after surgery. Second, although data were extracted from a prospective database, given its retrospective nature, selection bias may have influenced our findings. Finally, the sample size could be another limitation.

A little limitation for ADL is observed among patients undergoing thoracic or gastrointestinal surgery for cancer; however, advanced cancer, ASA class ≥3 and postoperative major complications are risk factors associated with disability. With regard to HRQoL, mobility, pain/ discomfort and anxiety/ depression are the most common affected dimensions. Advanced cancer, postoperative major complications and disability are risk factors associated with severe impairment in HRQoL. Recognizing these risk factors could aid in establishing a directed rehabilitation program for preventing disability and improve HRQoL in this population. Other studies confirming our results are required.

Nil.

None.

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

©2017 Benítez, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.