eISSN: 2576-4497

Research Article Volume 6 Issue 3

Epidemiology Department, Faculty of Public Health, Institute of health, Jimma University, Ethiopia

Correspondence: Mohammed Jihad, Department of Epidemiology, Faculty of Public Health, Institute of health, Jimma University, Ethiopia

Received: December 05, 2023 | Published: December 18, 2023

Citation: Jihad M, Woldemichael K, Gezehagn Y. Determinants of late initiation for Antenatal Care follow-up among pregnant mothers attending public health centers at Jimma Town, South West Ethiopia, 2021: unmatched case-control study. Hos Pal Med Int Jnl. 2023;6(3):86-93. DOI: 10.15406/hpmij.2023.06.00223

Background: The World Health Organization recommends that a woman without complications should have at least four antenatal care visits, the first of which should take place during the first trimester (not > 16 weeks). But a high proportion of pregnant women in most developing countries attended the first antenatal care at a late time. In Ethiopia, the magnitude of late antenatal care follow-up initiation is 64%, and in the study area, it is 68.7%. However, the determinants of the problem were not identified, particularly in the study area.

Objective: To identify determinants of late antenatal care initiation among pregnant women attending antenatal care in public health centers in Jimma Town, South West Ethiopia, 2021.

Methods: A facility-based unmatched case control study was conducted from May 1–30. The cases (n = 177) were mothers who attended their first antenatal care visit at >= 16 weeks of gestational age, and the controls (n = 177) were mothers who attended their first antenatal care visit at <16 weeks of gestational age during the data collection period. Data was collected through face-to-face interviews using a pre-tested, structured questionnaire. Descriptive and summary statistics were done. Bivariate and multivariable logistic regression analysis was done using SPSS version 21.0 to identify candidate variables at P-value <0.25 and determinants of late antenatal care initiation at P-value <0.05, respectively.

Results: The current study identified that age > 25 years (AOR = 2.623, 95% CI 1.059–6.496), poor knowledge about antenatal care (AOR = 3.856, 95% CI 1.266–11.750), lack of history of abortion (AOR = 3.326, 95% CI 1.082–10.224), place of previous delivery (AOR = 3.926, 95% CI 1.023–15.063), recognizing pregnancy through missed periods (AOR = 3.631, 95% CI 1.520–8.674), pregnancy-related pain (AOR = 3.499, 95% CI 1.423–8.603), and lack of family support (AOR = 2.647, 95% CI 1.092–6.415) were determinants of late antenatal care initiation.

Conclusion: Age > 25 years, poor knowledge about antenatal care, lack of history of abortion, place of previous delivery, recognizing pregnancy through missed period, pregnancy related pain, and lack of family support during antenatal care booking were determinants of late antenatal care initiation. Health facilities and respective health care providers should provide health education at the facility level regularly, with due attention to late antenatal care initiation.

Keywords: late antenatal care, determinant, jimma town

Late antenatal care initiation is the first antenatal care visit at >= 16 weeks of gestational age for the current pregnancy. Under normal conditions, the World Health Organization recommends that a woman without complications should have at least four antenatal care visits, the first of which should take place during the first trimester (not > 16 weeks).1 There are several risk factors associated with late antenatal booking and these may have an impact on maternal and fetal wellbeing, resulting in increased mortality and morbidity.1–4

Worldwide, there is a big discrepancy in the prevalence of late antenatal care follow-up among pregnant mothers, ranging from 27.5 to 88% in developed and developing countries respectively. Delayed initiation of antenatal follow-up is the predominant problem throughout Sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries failing to accomplish the World Health Organization recommendation.5,6

According to the systematic review and meta-analysis conducted on delayed initiation of antenatal care and associated factors in Ethiopia, the pooled estimate of the magnitude of delayed initiation of antenatal care in Ethiopia was 64%.7 A high proportion of pregnant women (60.5%) initiated antenatal care after four months of gestation.8–10 Mini EDHS 2014 revealed that only 18% of pregnant women initiated early for first antenatal care services.11 EDHS 2016 also showed that 42% of first antenatal care attendants were initiated later.12 A study conducted in Jimma Town, Ethiopia showed that 68.7% of participants initiated their first antenatal care lately.13 Late antenatal care registration and inadequate antenatal care attendance predispose pregnant women to an increased risk of maternal morbidity and mortality and poor pregnancy outcomes. Women who book late for antenatal care lose the opportunity to benefit from early detection and effective treatment of some disease conditions that may impair their health and that of their babies.14 Low birth weight, low Apgar scores as well as the incidence of maternal anemia and pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH) were found to be related to late antenatal care booking.15

Adverse pregnancy outcomes can be minimized or avoided altogether if antenatal care is received early in the pregnancy and continued through delivery. But every day in 2017, about 808 women died due to complications of pregnancy and childbirth. MMR in the world’s least developed countries (LDCs) is high, estimated at 415 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births, which is more than 40 times higher than MMR in Europe, and almost 60 times higher than in Australia and New Zealand. Almost all of these deaths occurred in low-resource settings, and most could have been prevented. The primary causes of death are hemorrhage, hypertension, infections, and indirect causes, mostly due to the interaction between pre-existing medical conditions and pregnancy.16,17 Many studies reported that late initiation of antenatal care was highly significant among less educated mothers, unplanned pregnancies, ages>26 years of mothers, unemployed women, husband’s education, women’s autonomy, knowledge of antenatal care, partner involvement, past pregnancy complication history, parity, anxiety of being pregnant, monthly income, place of residence, revealing pregnancy, means of checking pregnancy, late recognition of pregnancy, distance of health facility, place of previous delivery and not having experience of antenatal care.7,8,18–22

In Ethiopia, many studies indicated that antenatal care utilization during the first trimester is low and most pregnant women who attend antenatal care come too late for their first antenatal care visit ranging from 40 to 60%. Due to this reason, only four in 10 women (43%) had four or more antenatal care visits for their most recent live births. According to the Ethiopian EDHS report; the antenatal care service coverage was 41%, among those 23% of them initiated late for antenatal care.3,11 Despite having made considerable progress on an international level in terms of increasing the accessibility and use of antenatal care, the first consultation usually occurs at a late stage of pregnancy.23 The annual report of Jimma Town 2019/20 from DHIS2 also showed that a high proportion 64% of first antenatal care attendants were initiated lately.

In various parts of Ethiopia, numerous studies have been undertaken and written. However, the majority of them were designed to be cross-sectional, making it impossible to determine a causal association between the outcome and exposure variables. In addition, the determinants of late initiation for antenatal care are not the same across different cultures, socioeconomic status and access to institutions within a society. As a result, this research aims to find potential determinants of late antenatal care initiation among pregnant women attending antenatal care in public health centers in Jimma Town, southwest Ethiopia, in the year 2021.

Study area, design, and period

This study was conducted in Oromia Regional State, Jimma Town, which is 346 km from Addis Ababa to the southwest part of the country. Based on the 2007 national census, the estimated population of Jimma Town in 2020/21 is 220,609. Of these, 112,511 (51%) are females and 7655 Pregnant mothers. The town has 17 kebeles; 4 rural and 13 urban kebeles. There are 4 health centers, 2 public Hospitals and 3 private Hospitals in Jimma Town. The data collection period was May 1-30, 2021. Facility-based unmatched case-control study design was used.

Population

The source population was all pregnant women attending antenatal care in Jimma Town public health centers during the study period. The study population for cases was all eligible pregnant women who came for first antenatal care services at >=16 weeks of gestational age and the study population for controls was all eligible pregnant women who came for first antenatal care services at <16 weeks of gestational age in Jimma Town public health centers during the study period.

Sample size and sampling procedure

Sample size was calculated by Epi Info Version 7.0.8.3 using the double population proportion formula by considering that the proportion of mothers who had unplanned pregnancy among controls was 8.2% (the main predictor variable with AOR = 2.73 and a P-value <0.000) from a similar study conducted in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.24 In addition, 95% CI, 80% power, and 1:1 control to case ratio. Accordingly, by adding 10% of the non-response rate, the final sample size was 177 cases and 177 controls. There are four public health centers in Jimma Town, and the total sample size was proportionately allocated across all health centers according to their average three-month case load (Figure 1).

Selection of cases: For a woman who came for First antenatal care, the gestational age of the pregnancy was determined using LMP. Pregnant women with a gestational age of >=16 weeks (cases) were identified and selected using a systematic random sampling technique. The random start of the case selection was 4, and the interval was 2.

The interval was determined by the average of three months' cases flow divided by the sample size allocated to each facility, which is equal to two. The first mother was identified using simple random sampling, and the rest were selected at every interval until the allocated sample size was reached.

Selection of controls: Control selection was based on case selection; for each case selected, the immediate pregnant woman with a gestational age < 16 weeks (control) was identified and selected as a control.

Socio-economic status: measured based on five multiple-choice questions; for a correct response, 1 score was given; for an incorrect or don’t know the answer, 0 was given. The cumulative score ranges from 0 to 5. Finally, by using a modified Bloom’s cutoff point, categorization was made as 80–100% good knowledge, 50–79% moderate, and <50% poor knowledge.

Knowledge: was measured based on five multiple-choice questions; for a correct response, 1 score was given; for an incorrect or don’t know the answer, 0 was given. The cumulative score ranges from 0 to 5. Finally, by using a modified Bloom’s cutoff point, categorization was made as 80–100% good knowledge, 50–79% moderate, and <50% poor knowledge.

Service quality: was measured using Likert’s scale based on the satisfaction level of the mothers with health service delivery. Four questions were rated by mothers, and a score was given starting from 5-1; the cumulative score ranges from 4-20; then, using modified Bloom’s cutoff point, 80-100% was considered good quality, 50-79% moderate quality, and <50% indicates poor quality.

Data collection tools and procedures

A structured questionnaire with different sections was developed based on various literature sources. The questionnaire was initially prepared in English, translated into Afan Oromo, and then back-translated into English to maintain language consistency. Data collectors included eight diploma midwives and one BSc midwife supervisor who were involved in day-to-day activities. Two days of training were provided on the study objectives, subject identification, and questionnaire contents for data collectors, supervisors, and data clerks. Data was collected through face-to-face interviews in the waiting area following antenatal care consultations at the antenatal care unit. Respondents were informed about the study's purpose, privacy, confidentiality, and assured that the information provided would be kept in a secure box without recording names. The supervisor checked the data at the end of each day during the collection period to ensure completeness and consistency of the questionnaires. Following data collection, the questionnaires were sorted into two groups and numbered as 1 and 2 for controls and cases, respectively.

Data analysis procedure

Data was entered into EPI-data version 4.6 and then exported to SPSS version 21.0 for analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the data according to variable type. Bivariate and multivariable logistic regressions were conducted. Any variable with the outcome of interest at p < 0.25 in the bivariate analysis was considered for multivariable analysis. Multi-collinearity was assessed for all candidate variables using VIF (Variance Inflator Factor) with a cutoff point of 10, and model goodness of fit was evaluated using the Hosmer & Lemeshow test with a p value > 0.05. In the multivariable analysis, P < 0.05 was declared statistically significant. The AOR along with its respective 95% CI was computed to assess the association between independent variables and a dependent variable.

Ethical consideration

Ethical clearance was obtained from the ethical review board (IRB) of Jimma University. Based on the ethical clearance, an official letter was obtained from the Institute of Health, Faculty of Public Health, Department of Epidemiology. An official letter was submitted to the Jimma Town health office and health centers. After explaining the purpose of the study, permission was obtained from the head of the Jimma Town health office and the managers of health centers. Respondents were informed about the purpose of the study, the importance of their participation, and their right to withdraw at any time if they wanted. They were also informed about the privacy and confidentiality of the information given by each respondent, which was kept properly, and that names were not recorded. Written consent was obtained from each respondent.

Sociodemographic characteristics

In the current study, 177 cases and 177 controls participated, with a response rate of 100%. About 151 (85.3%) of cases and 162 (91.5%) controls were urban residents. The distribution of religion types among cases and controls was nearly the same. Regarding the age of the mothers, 96 (54.2%) and 43 (24.3%) of cases and controls were >25 years old, respectively. Almost all cases 168 (94.9%), and controls 167 (94.4%) were married. One hundred twenty-eight cases (72.3%) and 111 (62.7%) controls were unemployed. Regarding husband occupation, 110 (64%) of cases and 134 (76.6%) of controls were employed. Concerning socioeconomic status, 63 (35.6%) of cases and 55 (31.1%) of controls were in the category of poorest socio-economic status. While 57 (32.2%) of cases and 61 (34.5%) of controls were wealthiest (Table 1).

|

Variables |

Case n= 177 |

Control n =177 |

P-Value |

COR(95% CI) |

|

Residence |

|

|

|

|

|

Urban |

151(85.3%) |

162(91.5%) |

1 |

|

|

Rural |

26(14.7%) |

15(8.5%) |

.271 |

0.538(0.274-1.054) |

|

Religion |

|

|

|

|

|

Muslim |

126(71.2%) |

128(72.3%) |

1 |

|

|

Orthodox |

38(21.5%) |

37(20.9%) |

.872 |

0.958(0.573-1.604) |

|

Protestant |

11(6.2%) |

12(6.8%) |

.870 |

1.074(0.457-2.523) |

|

Other |

2(1.1%) |

0(0%) |

.999 |

.000 |

|

Age of mother |

|

|

|

|

|

>25 |

96(54.2%) |

43(24.3%) |

.000 |

3.693(2.347-5.811) |

|

<=25 |

81(45.8%) |

134(75.7%) |

1 |

|

|

Family size |

|

|

|

|

|

>3 |

76(42.9%) |

39(22%) |

.000 |

0.376(0.236-.597) |

|

<=3 |

101(57.1%) |

138(78%) |

1 |

|

|

Marital status |

|

|

|

|

|

Single |

7(4.0%) |

7(4.0%) |

.991 |

1.006(0.345-2.931) |

|

Divorced/widowed |

2(1.1%) |

3(1.7%) |

.655 |

1.509(0.249-9.147) |

|

Married |

168(94.9%) |

167(94.4%) |

1 |

|

|

Occupational status of mother |

|

|

|

|

|

Unemployed |

128(72.3%) |

111(62.7%) |

.054 |

1.553(0.99-2.432) |

|

Employed |

49(27.7%) |

66(37.3%) |

1 |

|

|

Occupational status of husband |

|

|

|

|

|

Unemployed |

62(36%) |

41(23.4%) |

.011 |

1.842(1.153-2.942) |

|

Employed |

110(64%) |

134(76.6%) |

1 |

|

|

Educational status of mother |

|

|

|

|

|

Can't read and write |

44(24.9%) |

16(9%) |

.000 |

4.583(2.284-9.197) |

|

primary (1-8) |

94(53.1%) |

96(54.2%) |

.002 |

2.809(1.482-5.321) |

|

Secondary (9-12) and above |

39(22%) |

65(36.7%) |

1 |

|

|

Educational status of husband |

|

|

|

|

|

Can't read and write |

26(15.1%) |

15(8.6%) |

.002 |

3.026(1.485-6.164) |

|

primary (1-8) |

87(50.6%) |

57(32.6%) |

.728 |

1.136(0.554-2.328) |

|

secondary (9-12) and above |

59(34.3%) |

103(58.9%) |

1 |

|

|

Socio economic status |

|

|

|

|

|

Poorest |

56(31.6%) |

68(38.4%) |

.322 |

1.495(0.898-2.486) |

|

Moderate |

57(32.2%) |

57(32.2%) |

.432 |

1.231(0.733-2.067) |

|

Wealthiest |

64(36.2%) |

52(29.4%) |

1 |

|

Table 1 Socio demographic characteristics of mothers for the research conducted on determinants of late ANC initiation, in Jimma Town, South West Ethiopia, 2021

Knowledge status of respondents about antenatal care

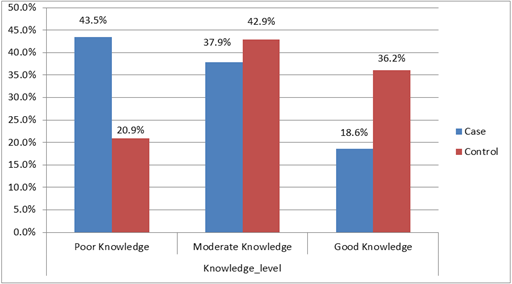

Seventy-seven (43.5%) of cases and 37 (20.9%) controls have poor knowledge about antenatal care. The proportion of moderate knowledge among cases and controls was 67 (37.9%) and 76 (42.9%), respectively. Thirty-three (18.6%) of cases and 64 (36.2%) of controls have good knowledge about antenatal care (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Knowledge status of mothers among case and control groups, Jimma Town, South West Ethiopia, 2021.

Maternal and obstetric characteristics of respondents

The proportion of multigravida among cases and controls was 112 (63.3%) and 81 (45.8%), respectively. Sixty-five (36.7%) of cases and 96 (54.2%) controls were primi-gravida. Mothers were asked if they had a history of abortion, and 18 (16.1%) of cases and 28 (34.6%) of controls reported a history of abortion. Concerning place of delivery for the last previous pregnancy, 25 (23.6%) of cases and 7 (10%) of controls gave birth at their home. One hundred thirty-three (75.1%) of cases and 68 (38.5%) of controls recognized their pregnancy through missed period. Regarding revealing being pregnant to others, 137 (77.4%) of cases and 169 (95.5%) of controls revealed their pregnancy (Table 2).

|

Variables |

Case (n=177) |

Control(n=177) |

P-Value |

COR(95% CI) |

|

Gravidity |

|

|

|

|

|

Multigravida |

112(63.3%) |

81(45.8%) |

.001 |

.490(0.320-0.749) |

|

Primigravida |

65(36.7%) |

96(54.2%) |

1 |

|

|

History of abortion |

|

|

|

|

|

No |

94(83.9%) |

53(65.4%) |

.003 |

2.759(1.396-5.452) |

|

Yes |

18(16.1%) |

28(34.6%) |

1 |

|

|

ANC history |

|

|

|

|

|

No |

20(17.9%) |

10(12.3%) |

.299 |

1.543(0.680-3.504) |

|

Yes |

92(82.1%) |

71(87.7%) |

1 |

|

|

Parity |

|

|

|

|

|

>=1 |

106(59.9%) |

70(39.5%) |

.197 |

1.492(0.813-2.739) |

|

Parity 0 |

71(40.1%) |

107(60.5%) |

1 |

|

|

Place of delivery for the last previous pregnancy |

|

|

|

|

|

Home |

25(23.6%) |

7(10%) |

.026 |

2.778(1.129-6.835) |

|

Health facility |

81(76.4%) |

63(90%) |

1 |

|

|

Pregnancy status (planned/unplanned) |

|

|

|

|

|

No |

66(37.3%) |

17(9.6%) |

.000 |

5.596(3.116-10.050) |

|

Yes |

111(62.7%) |

160(90.4%) |

1 |

|

|

Revealing being pregnancy to others |

|

|

|

|

|

No |

40(22.6%) |

8(4.5%) |

.000 |

6.168(2.794-13.615) |

|

Yes |

137(77.4%) |

169(95.5%) |

1 |

|

|

Pregnancy recognition means |

|

|

|

|

|

By missed period |

133(75.1%) |

68(38.4%) |

.000 |

4.845(3.071-7.644) |

|

By Urine test |

44(24.9%) |

109(61.6) |

1 |

|

|

Current pregnancy related pain before initiation |

|

|

|

|

|

Yes |

87(49.2%) |

48(27.1%) |

.000 |

2.598(1.667-4.048) |

|

No |

90(50.8%) |

129(72.9%) |

1 |

|

|

GA of pregnancy recognition |

|

|

|

|

|

>=8 weeks |

150(84.7%) |

132(74.6%) |

.018 |

1.894(1.113-3.222) |

|

<8 weeks |

27(15.3%) |

45(25.4%) |

1 |

|

|

History of CS delivery |

|

|

|

|

|

No |

98(92.5%) |

58(82.9%) |

.026 |

2.778(1.129-6.835) |

|

Yes |

8(7.5%) |

12(17.1%) |

1 |

|

Table 2 Bivariate Analysis of Maternal and Obstetric Factors Associated with Late Antenatal Care Initiation in Jimma Town, South-West Ethiopia, 2021

Health service related factors

Regarding service quality, 82 (46.3%) of cases and 84 (47.5%) of controls rated service quality as moderate. Fifty-two (29.4%) and 29 (16.4%) cases and controls rated service quality as poor, respectively. Concerning distance from a health facility, 118 (66.7%) cases and 130 (73.4%) controls were near a health facility (Table 3).

|

Variables |

Case (n= 177) |

Control (n= 177) |

P-Value |

COR (95%CI) |

|

Service quality |

|

|

|

|

|

Poor |

52(29.4%) |

29(16.4%) |

.001 |

2.669(1.470-4.845) |

|

Moderate |

82(46.3%) |

84(47.5%) |

.029 |

1.837(1.063-3.173) |

|

Good |

43(24.3%) |

64(36.2%) |

1 |

|

|

Distance from health facility |

|

|

|

|

|

Far |

59(33.3%) |

47(26.6%) |

.164 |

1.383(0.876-2.184) |

|

Near |

118(66.7%) |

130(73.4%) |

1 |

|

Table 3 Bivariate Analysis of Health Service-Related Factors Associated with Late Antenatal Care Initiation in Jimma Town, South West Ethiopia, 2021

Sociocultural characteristics

One hundred twenty-six (71.2%) of cases and 158 (89.3%) controls made decisions to book for antenatal care follow-up in consultation with their husbands. Regarding family support, 118 (66.7%) cases and 55 (31.1%) controls came to the health facility alone during antenatal care initiation (Table 4).

|

Variables |

Case (n= 177) |

Control (n= 177) |

P-Value |

COR (95%CI) |

|

Decision making to book for antenatal care |

|

|

|

|

|

My Self |

45(25.4%) |

16(9%) |

.000 |

3.527(1.904-6.534) |

|

with Other relative |

6(3.4%) |

3(1.7%) |

.656 |

1.406(0.314-6.294) |

|

with my husband |

126(71.2%) |

158(89.3%) |

1 |

|

|

Family support |

|

|

|

|

|

Alone |

118(66.7%) |

55(31.1%) |

.000 |

5.185(3.259-8.248) |

|

with Other relative |

11(6.2%) |

6(3.4%) |

.768 |

1.170(0.412-3.327) |

|

with my husband |

48(27.1%) |

116(65.5%) |

1 |

|

Table 4 Socio-cultural characteristics of respondents, Jimma Town, South West Ethiopia 2021

Determinants of late initiation of antenatal care follow-up

Mothers aged >25 years were 2.623 times more likely to initiate antenatal care follow-up late as compared to their counterparts (AOR = 2.623, 95% CI 1.059–6.496). Pregnant mothers who have poor knowledge about antenatal care were 3.856 times more likely to book late for antenatal care as compared to those who have had good knowledge (AOR = 3.856, 95% CI 1.266–11.750). Mothers who hadn't had a history of abortion were 3.326 times more likely to book late for antenatal care follow-up as compared to those who had an abortion history (AOR = 3.326, 95% CI 1.082–10.224). Mothers who gave birth at their home during the last previous delivery were 3.926 times more likely to book late for antenatal care as compared to mothers who gave birth at a health facility (AOR = 3.926, 95%CI 1.023–15.063).

Pregnant mothers who recognized their pregnancy by missed period were 3.631 times more likely to book late for antenatal care follow-up as compared to those recognized by urine test (AOR = 3.631, 95% CI 1.520–8.674). Mothers who wait until they feel ill from pregnancy were 3.499 times more likely to book late for antenatal care follow-up as compared to those who initiated without feeling pain from pregnancy (AOR = 3.499, 95% CI 1.423–8.603). Mothers who came to health facilities alone during antenatal care booking were 2.647 times more likely to initiate late for antenatal care follow-up as compared to those who came with their husbands (AOR = 2.647, 95% CI 1.092–6.415) (Table 5).

|

Variables |

Case(n=177) |

Control(n=177) |

COR (95% CI) |

AOR (95% CI) |

|

Age of mother |

|

|

|

|

|

>25 |

96(54.2%) |

43(24.3%) |

3.693 (2.347-5.811)* |

2.623(1.059-6.496)** |

|

<=25 |

81(45.8%) |

134(75.7%) |

1 |

|

|

Knowledge about ANC |

|

|

|

|

|

Poor Knowledge |

77(43.5%) |

37(20.9%) |

4.036(2.272-7.170)* |

3.856(1.266-11.750)** |

|

Moderate Knowledge |

67(37.9%) |

76(42.9%) |

2.361(1.415-3.937)* |

1.98(0.424-3.381) |

|

Good Knowledge |

33(18.6%) |

64(36.2%) |

1 |

|

|

History of abortion |

|

|

|

|

|

No |

94(83.9%) |

53(65.4%) |

2.759 (1.396-5.452)* |

3.326(1.082-10.224)** |

|

Yes |

18(16.1%) |

28(34.6%) |

1 |

|

|

Place of delivery for the last previous pregnancy |

|

|

|

|

|

Home |

25(23.6%) |

7(10%) |

2.778 (1.129-6.835)* |

3.926(1.023-15.063)** |

|

Health facility |

81(76.4%) |

63(90%) |

1 |

|

|

Pregnancy recognition Means |

|

|

|

|

|

By missed period |

133(75.1%) |

68(38.4%) |

4.845 (3.071-7.664)* |

3.631(1.520-8.674)** |

|

By Urine test |

44(24.9%) |

109(61.6) |

1 |

|

|

Current pregnancy related pain before initiation |

|

|

|

|

|

Yes |

87(49.2%) |

48(27.1%) |

2.598 (1.667-4.048)* |

3.499(1.423-8.603)** |

|

No |

90(50.8%) |

129(72.9%) |

1 |

|

|

Family support |

|

|

|

|

|

Alone |

118(66.7%) |

55(31.1%) |

5.185(3.259-8.248) * |

2.647 (1.092-6.415)** |

|

with Other relative |

11(6.2%) |

6(3.4%) |

1.170(0.412-3.327) |

1.323(0.133-13.139) |

|

with my husband |

48(27.1%) |

116(65.5%) |

1 |

|

|

*Significant variables in bivariable analysis, **Significant variables in Multivariable analysis |

||||

Table 5 Independent predictors of late antenatal care initiation, Jimma Town, South West Ethiopia, 2021

The current study showed that age > 25 years old, poor knowledge about antenatal care, lack of history of abortion, previous home delivery, recognizing pregnancy through missed period, current pregnancy related pain before initiation, and lack of family support during antenatal care booking were determinants of late antenatal care initiation.

Pregnant mothers aged >25 were 2.6 times more likely to book late antenatal care follow-up as compared to their counterparts. This result is consistent with the studies done in Debremarkos, Kembata, and East Wellega, Ethiopia.5,25,26 The reason might be that young women have more health-seeking behavior and information about the importance of early antenatal care booking than older women.

Pregnant mothers who have had poor knowledge about antenatal care were 3.38 times more likely to book late for antenatal care follow-up as compared to those who have had good knowledge. This finding is in line with the study conducted in Tigray, Ethiopia. Kahasse G,24 his could be explained by the fact that mothers with poor knowledge might not have awareness about the correct time for antenatal care booking, the frequency of antenatal care visits, and the importance of antenatal care follow-up both for the mother and the fetus. In the current study, pregnant mothers who had no history of abortion were 3.3 times more likely to book late for antenatal care follow-up as compared to their counterparts. The study finding is supported by the study done in the United Arab Emirates and Ethiopia.20–28 It could be explained by the fact that mothers who have a history of abortion were more likely to initiate early antenatal care follow-up due to fear of recurrence of the event, as well as the fact that they might have gotten information about antenatal care follow-up during the previous event.

The finding showed that mothers who gave birth at home during the last previous delivery were 3.9 times more likely to book late for antenatal care follow-up as compared to those who gave birth at a health institution during the previous delivery. This finding is in line with the study conducted in Ethiopia.21 It might be due to the fact that mothers who gave birth at the health facility during previous deliveries benefitted and got information about antenatal care follow-up and appropriate booking time. Mothers who recognized their pregnancy through missed period were 3.6 times more likely to book antenatal care late as compared to mothers who recognized their pregnancy by urine test. A similar finding was also reported in studies conducted in North Ethiopia5,29,30 Mothers who recognize their pregnancy through a urine test might be more likely to seek health care and accept modern medical care follow-up than those who recognize it via a missed period. On the other hand, mothers who recognized pregnancy by missed period were most probably after missing one or two cycles, and thereafter, they might be reluctant to start antenatal care soon.29

Pregnant mothers who wait until they feel ill from pregnancy to start antenatal care follow-up were about 3.5 times more likely to book antenatal care follow-up late as compared to their counterparts. This finding is consistent with the study conducted in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.31 The possible explanation could be due to the wrong perception of antenatal care follow-up as curative rather than preventive and waiting for pregnancy related medical problems to book antenatal care. Pregnant mothers who came alone to health facilities during antenatal care booking were 2.64 times more likely to initiate antenatal care follow-up lately as compared to those accompanied by their husbands. This finding is supported by the studies done in Tanzania and Ethiopia.9,19,32 This could be due to a lack of encouragement from husbands, which may deter women from obtaining early antenatal care.

The current study showed that family size, parity, pregnancy status, and revealing being pregnant to others were not significantly associated with late antenatal care booking. Family size has no statistically significant relationship with late antenatal care booking. The result is different from the study conducted in sub-Saharan Africa and Cameroon.33,34 It might be due to the difference in sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants in the two study areas.

Contrary to a study conducted in Cameroon and Boke Woreda, Ethiopia,18,36 parity was not shown to be linked with late antenatal care initiation. It might be due to the distribution of multipara and nulliparous among cases and controls was nearly similar, and hidden the impacts of parity on late antenatal care follow-up initiation. Pregnancy status was another insignificant variable in the current study. In contrast, the finding is different from studies conducted in Kembata and Gonder, Ethiopia.25,27 In the current study, the majority of respondents were married, and the probability of an unplanned pregnancy is low. So, fewer unplanned pregnancies among participants was the reason.

Misclassification bias might be introduced since gestational age was determined using LMP based on the woman’s memory. In addition, the current study focused solely on public health centers in Jimma Town, with no mention of public hospitals, private clinics, or private hospitals.

The study identified that age > 25 years, poor knowledge about antenatal care, previous home delivery, recognizing pregnancy through missed period, current pregnancy related pain before initiation, and lack of family support during antenatal care booking were determinants of late antenatal care initiation in the current study. Health care providers should provide health education at the facility level regularly, with due attention to the late initiation of antenatal care and the eligibility of all pregnant mothers regardless of feeling pregnancy related medical problems. While providing health education, special consideration should be given to mothers aged > 25 years.

We would like to express our heartfelt appreciation to all participants of the study, Jimma University, and Jimma Town Health Office for their unwavering support and dedication.

The author declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

©2023 Jihad, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.