eISSN: 2576-4497

Review Article Volume 3 Issue 4

1Pedro Ernesto University Hospital, State University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

2National Cancer Institute, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Correspondence: Daiane Spitz de Souza, Nutritionist, Pedro Ernesto University Hospital, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Received: July 10, 2019 | Published: July 29, 2019

Citation: Lopes JR, Castanho IA, Carvalho CS, et al. Applicability of patient-generated subjective global assessment in palliative care. Hos Pal Med Int Jnl.2019;3(4):138-145. DOI: 10.15406/hpmij.2019.03.00167

Context and objective: Palliative care aims at promoting quality of life, symptoms management and alleviating suffering. Nutrition plays an important role in the early identification of these symptoms by the use of tools such as Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA). The objective of the study is to describe the nutritional status and the prevalence of symptoms using PG-SGA on palliative care patients. We also correlate PG-SGA with clinical characteristics and functional status.

Method: A cross-sectional study was conducted in patients followed at the palliative care outpatient clinic from May 2009 through May 2015. On admission, the PG-SGA was filled out and the Karnofsky Performance Scale (KPS) was obtained. Correlation between PG-SGA and KPS was performed by statistical inference and analysis of variance.

Results: 104 patients were included in the analysis. Most of the patients were classified as moderately or severely malnourished and had a score greater than or equal to 9. Tumor sites with the highest frequency of severe malnutrition were pulmonary and colorectal. The most prevalent nutritional symptoms were hyporexia, constipation, nausea, pain, and early satiety. The KPS had a statistically significant association with the PG-SGA. Most patients with KPS≤40% were classified as PG-SGA-C (p=0.002) and patients with KPS³70% were PG-SGA A or B (90%). Patients with a numerical score greater than or equal to 9 had a lower KPS mean (p <0.001).

Conclusion: PG-SGA should be used to evaluate the nutritional status of patients in palliative care. We could strongly correlate the PG-SGA with KPS. Such information helps to guide the best intervention on symptom management, considering that the primary goal of palliative care is to promote quality of life.

Keywords: nutritional status, malnutrition, nutritional assessment, palliative care, cancer

The incidence of cancer is increasing worldwide,1 and many advances are still needed in cancer care. In Brazil, many types of cancer, especially lung and cervical cancer, are often detected in advanced stages.2 These patients are often referred to palliative care soon after the initial diagnosis. Palliative care improves the quality of life of patients and support families facing life-threatening illness. The cornerstone of the palliative treatment is prevention and relief of suffering through early symptoms identification, pain management and also psychosocial and spiritual support.3

Nutrition plays an important role in the palliative care by alleviating symptoms, promoting comfort, and improving the quality of life of advanced cancer patients.4 These patients often have nutritional impact symptoms that directly interfere with food ingestion of such as pain, xerostomia, anorexia, diarrhea, constipation, vomiting, nausea, chewing and swallowing impairment, dysgeusia, early satiety and dysosmia. Previous studies indicate that nausea, vomiting, early satiety, dysgeusia and dysphagia are directly related to cachexia.5,6

Cachexia is a multifactorial syndrome that occurs in different diseases causing loss of muscle mass, asthenia, apathy, immunodeficiency and loss of health-related quality of life.7 It can be classified according to its severity as pre-cachexia, cachexia and refractory cachexia, according to the intensity of weight loss, Body Mass Index (BMI), presence of hyporexia or anorexia, metabolic and inflammatory markers changes, sarcopenia, functionality and overall survival.8 Moreover, cachexia is considered a cause of mortality in 40% of cancer patients.

Ottery et al. demonstrated the treatment and prevention of cachexia using appropriate interventions guided by standardized nutritional assessment tools. They were able to achieve maintenance or weight gain in 50% of patients who underwent oncologic treatment by their methods.9 Based in these finds, available instruments for symptoms evaluation, such as visual, numerical, facial, colored and visual scales questionnaire must be used in order to identify patients at nutritional risk in which intervention can be applied.10

Among the instruments used in symptoms identification and nutritional status classification, the Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA) stands out. It is a nutritional screening tool originally applied to evaluate surgical patients, and later its use was extended to other populations.11 PG-SGA is now considered a useful tool for nutritional evaluation by the Oncology Nutrition Dietetic Practice Group of the American Dietetic Association.11,12

In addition to nutritional status deterioration, loss of functional capacity is often observed in patients with advanced cancer. For classification of the functional status, simple tools such as the Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) have been widely used. The KPS is a scale of easy application and interpretation that stratifies patients according with the ability to perform daily tasks and work, it also considers the need for care.13 Due to its relation with the prognosis, it can be used as a guide in treatment plan and overall survival prediction.14

Symptoms, impairment of functional capacity, antineoplasic treatment, and comorbidities may interfere with appetite, eating and food digestion.15 Patients with advanced cancer are at risk of nutritional deficiency, as well as loss of appetite, weight loss and fatigue.10 These symptoms may cause deterioration of functional capacity and, consequently, decrease quality of life.16 However, nutrition impact symptoms may be overlooked in some cases because pain management is often the first concern in palliative care settings.

Our study aims to describe, through the PG-SGA, the nutritional profile and prevalence of nutritional impact symptoms in cancer patients and correlate them with clinical characteristics and KPS.A cross-sectional quantitative analysis was carried out at the palliative care outpatient clinic of a tertiary hospital. Data collection was performed in the medical record of patients accessed by PG-SGA between May 2009 and May 2015. Patient demographics, histopathological diagnosis, clinical and pathological stages, KPS, BMI, comorbidities, use of opioids and laxatives were extracted from our prospectively maintained nutritional database.

PG-SGA was applied by the nutrition team at the first patient visit. The first part of this tool, which includes data on the history of weight loss, altered food intake, presence of nutritional impact symptoms and functional activity, was answered by the patient or by family member. The second part, which includes questions related to diagnosis, metabolic needs and physical examination, was answered by the nutrition professional.

After completing all the data, the nutritionist performed the sum of the points of each component generating a score, ranging from 0 to 9. According to the numerical score, PG-SGA presents different types of nutritional interventions, where: 0 to 1 point no nutritional intervention is required; between 2 and 3 points, nutritional education of the patient or family is suggested; between 4 and 8 points nutritional intervention by nutritionist is required; and≥9 points indicates a critical need for symptom control and/or nutritional intervention. In addition to quantitative classification, a classification by groups was performed, in which the patient was classified as: well-nourished or anabolic (SGA-A); moderately malnourished or suspected of malnutrition (SGA-B); or severely malnourished (SGA-C).

The KPS of the first visit was used for analysis and classification of functional status. The health professional classified the patient's KPS between 100 and 0%, in which each percentage reflects a level of functionality, being classified as 100% the patient with normal activity without signs of disease up to 0% corresponding to death.

All patients older than 18 years that was evaluated by the nutrition team after completing the PG-SGA evaluation was included in our analysis. We excluded patients with no physical, psychological or cognitive ability to respond to the PG-SGA questionnaire, as well as all patients without complete data in the medical records.

Data were expressed as mean, standard deviation (±SD) or median, with minimum and maximum values for the numerical variables, according to the normality of the variables and proportion for the categorical variables. Multiple comparisons of numerical variables between three or more groups were performed using the ANOVA test. Parametric correlations were tested using the Pearson correlation coefficient. The associations between the categorical variables were evaluated with the Chi-square test. All analyzes were performed in the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 17.0. For all statistical tests the significance level of 5% was adopted.

The research was carried out with the approval of the Ethics Committee. Informed consent was not necessary since it is a revision of records with guarantee of confidentiality, whose data were analyzed and exposed anonymously, and the results presented in aggregate form and no intervention was performed.

104 patients were included in the analysis. Mean age was 64.9±13.0 years, 59.6% were men. Among comorbidities, the most frequent was cardiovascular disease and diabetes in 46.1% patients. Other comorbidities such as rheumatoid arthritis, epilepsy and hepatitis were reported in 10.6% of the studied population. On the first visit at the palliative care clinic, the use of opioids was reported by 40.2% patients and use of laxatives by 3.8%. Regarding functional status, the median KPS was 58.6±17.3%, and 47.3% of the evaluated individuals presented KPS between 40 and 70%.

Regarding tumor site, lung and head and neck were the most prevalent, with 18.3% for both, followed by urological and colon and rectal tumors with 15.4% each. All patients were in stage IV of the disease, 64.4% had distant disease in which 38.8% bone, 26.9% lung and 25.4% liver metastasis (Table 1).

|

|

n (%) |

Age |

<60 years |

36 (34.5) |

≥60 years |

68 (65.4) |

|

Sex |

Female |

42 (40.4) |

Male |

62 (59.6) |

|

Education |

Illiteracy |

03 (02.9) |

Incomplete primary education |

37 (35.6) |

|

Complete primary education |

29 (27.9) |

|

Incomplete high school |

04 (03.8) |

|

Complete high school |

23 (22.1) |

|

Incomplete higher education |

02 (01.9) |

|

Complete higher education |

06 (05.8) |

|

Comorbidities |

Diabetes and/or Hypertension |

48 (46.1) |

Others |

11 (10.6) |

|

Without comorbidities |

45 (43.3) |

|

Use of Medications |

Laxatives |

04 (03.8) |

Opioids |

41 (40.2) |

|

KPS |

≤ 40% |

28 (30.8) |

40 - 70% |

43 (47.3) |

|

> 70% |

20 (22.0) |

|

Diagnosis |

Head and neck |

19 (18.3) |

Colon and Rectum |

16 (15.4) |

|

Urological |

16 (15.4) |

|

Gynecological |

04 (03.8) |

|

Hematological |

01 (01.0) |

|

Breast |

06 (05.8) |

|

Lung |

19 (18.3) |

|

Upper GI |

13 (12.5) |

|

Others |

10 (09.6) |

|

Metastases |

Liver |

17 (25.4) |

Bone |

26 (38.8) |

|

Lung |

18 (26.9) |

|

|

No metastasis |

37 (35.6) |

Table 1 Patients demographics, social and clinical characteristics

KPS, karnofsky performance status; GI, gastrointestinal

Analyzing the PG-SGA nutritional status, 24.0% of patients were classified as well-nourished (SGA-A), 41.3% moderately malnourished (SGA-B), and 34.6% as severely malnourished (SGA-C). The average PG-SGA score was 14.0±7.4 points (1-31), 76.0% had a score greater than or equal to 9. Regarding BMI, most patients (54.8%) were classified as underweight (Table 2).

Parameter |

Ranking |

n (%) |

PG-SGA groups |

A |

25 (24.0) |

B |

43 (41.3) |

|

C |

36 (34.6) |

|

PG-SGA score |

Jan-00 |

03 (02.9) |

3-Feb |

10 (09.6) |

|

8-Apr |

12 (11.5) |

|

≥9 |

79 (76.0) |

|

BMI |

Underweight |

34 (54.8) |

Normal weight |

16 (25.8) |

|

|

Overweight |

12 (19.4) |

Table 2 Patient-generated subjective global assessment nutritional status (n=104) and the body mass index (n=62)

PG-SGA, patient-generated subjective global assessment; A, well nourished; B, moderately malnourished; C, severely malnourished; BMI, body mass indexAnalyzing the PG-SGA nutritional status, 24.0% of patients were classified as well-nourished (SGA-A), 41.3% moderately malnourished (SGA-B), and 34.6% as severely malnourished (SGA-C). The average PG-SGA score was 14.0±7.4 points (1-31), 76.0% had a score greater than or equal to 9. Regarding BMI, most patients (54.8%) were classified as underweight (Table 2).

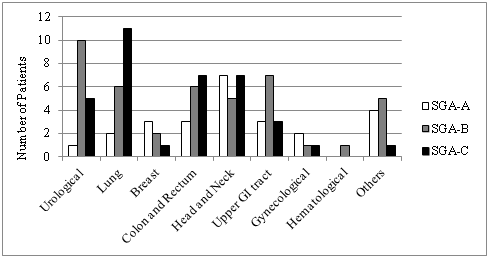

Tumor sites presenting poor nutritional status according to the PG-SGA were lung and colorectal, 57.9% and 43.7% were SGA-C, respectively. Regarding numerical score, genitourinary (93.8%) and colorectal (87.5%) had higher frequency score≥9 (Figure 1 and 2).

Figure 1 Diagnosis by patient-generated subjective global assessment groups.

*GI, Gastrointestinal; SGA-A, well nourished; SGA-B, moderately malnourished; SGA-C, severely malnourishedMetastatic patients presented higher nutritional impairment when compared to locally advanced disease, 46.9% and 34.4%, respectively (p=0.056).

When food intake and nutritional status was evaluated by PG-SGA, it was found that 26.9% patients reported severe weight loss (greater than 5% in one month or more than 10% in the last six months). The majority (56.7%) reported reduction in food intake; 23.1% reported consuming solid food in smaller quantities and 11.5% consume very little of nothing. Gastrointestinal symptoms in the last two weeks was reported by 76.0% and loss of appetite by 49.0%, followed by constipation (36.5%), nausea (32.7%), pain (31.7%) and early satiety (30.8%) (Table 3).

|

n (%) |

Loss of appetite |

51 (49.0) |

Nausea |

34 (32.7) |

Vomiting |

08 (07.7) |

Constipation |

38 (36.5) |

Diarrhea |

07 (06.7) |

Mouth sores |

08 (07.7) |

Xerostomia |

30 (28.8) |

Dysgeusia |

22 (21.2) |

Dysosmia |

09 (08.7) |

Dysphagia |

20 (19.2) |

Early satiety |

32 (30.8) |

Pain |

33 (31.7) |

Others |

14 (13.5) |

Table 3 Nutrition Impact Symptoms

Note: Patients may report more than one symptom.According to the tumor site, head and neck (52.6%) and lung cancer (36.8%) patients more often reported dysphagia (p=0.009). It is noteworthy that 47.1% head and neck cancer patients were already referred to our clinics with enteral feeding such as nasogastric tube or gastrostomy. Upper gastrointestinal tract cancer patients had the greatest association (76.9%) with inappetence (p=0.009). Meanwhile, breast cancer patients had the highest prevalence (83.3%) of decreased food intake (p=0.012).

Regarding tumor extension, the majority of patients with distant metastasis reported reduced food intake (65.6%; p=0.012). When correlating changes in dietary patterns to the presence of distant metastasis, 37.5% of these patients were using enteral nutrition (p=0.035), six had head and neck cancer and two esophageal cancer, of which seven had gastrostomies.

Considering physical exam, head and neck and lung cancer patients had higher prevalence of moderate or severe deficit (68.4% for both; p=0.002). When analyzing functional status by PG-SGA, 51.0% of these patients reported low activity or spend most of time in bed. Functional status was also assessed by KPS. We found statistically significant association between KPS groups and PG-SGA score. Most patients with KPS ≤ 40% was classified as SGA-C (60.7%; p=0.002), while patients with KPS >70%, were classified as SGA-A or SGA-B. Patients with numerical score≥9 had lower mean KPS (55.8%; p<0.001) (Table 4).

|

|

KPS (%±SD) |

P-value |

PG-SGA groups |

A |

70.5±16.4 |

0.002 |

B |

60.5±15.4 |

||

C |

49.4±15.0 |

||

PG-SGA score |

1-0 |

85.0±07.1 |

< 0.001 |

2-3 |

65.0 ±21.4 |

||

4-8 |

66.4±16.3 |

||

|

≥9 |

55.8±17.3 |

|

Table 4 Association between patient-generated subjective global assessment and karnofsky performance status

PG-SGA, patient-generated subjective global assessment; A, well nourished; B, moderately malnourished; C, severely malnourished; SD standard deviation; KPS, karnofsky performance statusMost patients in palliative care have advanced disease and often present weight loss and cachexia. Cancer cachexia is characterized by an increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines (such as tumor-α necrosis factor, interferon-γ, interleukin-1 and -6). It also changes signaling pathways neuropeptides and induce proteolysis and lipid-mobilizing factor.7 All these changes contribute to weight loss. Thus, the evaluation of weight loss is fundamental in determining nutritional risk, since a significant or severe loss may have negative outcomes for the patient.5

Severe weight loss was evidenced in most patients in our study. Regarding BMI nutritional status, more than half was underweight. However, anthropometry can be difficult to perform in patients with advanced disease due to physical impairment. In this setting, PG-SGA is a reliable tool with greater applicability in this group of patients. Moreover, depletion of nutritional status negatively influences the quality of life, the immune system, functional status and survival.16,17 This said, PG-SGA can be an important tool in planning the nutritional intervention in patients in palliative care.18

In the current study, we observe that when assessed by PG-SGA, most patients presented some degree of moderate (41.3%) or severe malnutrition (34.6%). In a study conducted in China, half of the patients in palliative care were classified by PG-SGA as moderately malnourished (50.0%), and only 19.0% as severely malnourished.5 In a study conducted in Brazil, the authors found that half of the population were moderate malnutrition (50.3%) and a prevalence of severe malnutrition were close to those observed in our study.16

Another study carried out in Brazil analyzing elderly cancer patients with different disease stages,19 found that 43.8% of the patients had some degree of malnutrition (moderate or severe) and 47.9% needed critical nutritional intervention (score≥9). In our study, 76.0% of the patients had a score ≥9. Souza Cunha et al. also found a high prevalence of patients with a score of ≥9 (70.7%) and suggested that a score ≥ 19 predicted death within 90 days.20

According to the qualitative PG-SGA classification, patients with lung and colorectal cancer had the highest frequency of severe malnutrition. These two groups tend to have a considerable reduction in weight, occurring in about 60% of lung cancer and 80% of cancers in the gastrointestinal tract, according to a Brazilian multicenter epidemiological study.11,21 Patients with lung cancer have increased energy expenditure which is influenced by the increase of inflammatory cytokines, deterioration of lung function, tumor growth, and smoking, which may also decrease appetite.22 In colorectal cancer, the occurrence of intestinal obstruction and related symptoms may compromise nutritional status.23

When stratified by tumor site, our analysis shows that urological and colorectal tumors had highest frequency of score ≥9, which may be related to the greater number of symptoms reported as inappetence, constipation and early satiety. Previous study shows that the PG-SGA score is adversely affected by the presence of symptoms of nutritional impact and that this method allows us to prioritize patients who need urgent treatment and, thus, facilitate the use of resources with greater effectiveness and earlier intervention.12

In our analysis we observed that the presence of gastrointestinal symptoms in the last two weeks was reported by 76% of the patients. In a previous study, the most reported nutritional impact symptoms were pain, xerostomia, hyporexia, and constipation.5 In the present study, the most reported symptoms were very similar, with higher frequency for hyporexia, constipation, nausea and pain.

Regarding the prevalence of symptoms by tumor site, gastrointestinal tumors had the greater association with hyporexia and inappetence. Previous publication analyzing patients with advanced gastrointestinal cancer found that 80.7% had reduced food intake.24 We should consider that the portion of the digestive tract affected will influence the worsening of nutritional status. In distal segments of the digestive tube, such as colorectal cancer, there is less impairment of digestion and absorption of nutrients. However, esophageal cancer impairs swallowing. Meanwhile, gastric cancer alters digestion and, indirectly, nutrients absorption as well as reducing food intake and weight loss.25

Head and neck and lung cancer patients were the ones that most reported dysphagia, in which 47.1% of patients with head and neck cancer had enteral feeding tubes. These two groups also had the highest prevalence of moderate or severe deficit assessed by physical exam. For head and neck patients, dysphagia usually accompanies the more advanced stages, and many patients were diagnosed in stages III and IV of the disease.26 These patients are at risk since the toxicity of the oncological treatments increases the risk of malnutrition. In addition, smoking, alcohol consumption and low socioeconomic status are frequent in this population, increasing the nutritional risk. For this reason, patients with advanced head and neck cancer often require nutritional support.27

Regarding lung cancer patients, it has been previously reported that sarcopenia may be one of the causes of dysphagia, where there is loss of musculature impairing in the swallowing process.28 In addition, larger lung tumors can compress the esophagus and cause dysphagia.

In addition to tumor site, the presence of nutritional impact symptoms may also be related to oncological treatments. Xerostomia, for example, may be the result of surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or drugs side effects.10

In a study evaluating palliative care patients,5 the authors found that 67.0% received opioid. Here, 40.2% of our patients populations reported using opioids at the time of admission to palliative care. The frequent use of opioids can worsen gastrointestinal symptoms and about 70-90% report intestinal constipation related to its use.29 Intestinal constipation was the second most reported symptom in the present study. In this group, only a small proportion of patients reported laxative use, probably because the data were collected on the first visit or perhaps because of poor adherence of patients to the use of laxatives. In another study in palliative care, 73.0% of the patients used laxatives, being more frequent in patients been treated with opioids.30

Cancer cachexia, the toxicity of cancer treatments, the side effects of medications, the tumor location, and the nutritional impact symptoms will lead to hyporexia, to protein catabolism, and to muscle depletion. These factors together intensify at more advanced stages of the disease and will result in loss of functionality.31 When we investigate the PG-SGA functionality, more than half of the participants reported little activity or spent most of their time in bed. Functional status, as measured by KPS, was inversely related to the PG-SGA score.

The combined use of PG-SGA with KPS allows the complete evaluation of different nutritional aspects and functional status. Since the deterioration of nutritional and functional status are common in advanced cancer patient, application of non-invasive nutritional assessment methods is highly indicated. In palliative care, weight monitoring alone is not significant. We should consider that the family and also the patient often associate weight loss with progressive deterioration of health status and that this can generate anxiety and frustration for both parts.11

Due to the above-mentioned reasons, it is extremely important to use the PG-SGA seeing that it does not require great physical strength and mobility of the patient. Regarding all that aspects evaluated by this tool, nutrition impact symptoms is one of the most important because early diagnosis and treatment of these symptoms can delay the cancer cachexia process and improve quality of life.15,16 We suggest that PG-SGA should be used during all course of the palliative care. Future studies regarding the impact of specific nutritional interventions on symptoms, on nutritional status, on functional capacity and in quality of life are awaited to corroborate our findings.

PG-SGA should be used to evaluate the nutritional status of patients in palliative care. This tool allows the detection of nutrition impact symptoms and indicates patients that are at nutritional risk. Moreover, we could strongly correlate the PG-SGA with KPS. Such information helps to guide the best intervention on symptom management, considering that the primary goal of palliative care is to promote quality of life.

None.

None.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

©2019 Lopes, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.