eISSN: 2576-4462

Research Article Volume 5 Issue 5

1Technology Consultancy Centre, College of Engineering, KNUST, Kumasi, Ghana

2Faculty of Natural Resources, College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, KNUST, Kumasi

3Department of Mathematics, College of Science, KNUST, Kumasi, Ghana

4Forest Research Institute of Ghana, Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, Kumasi, Ghana

Correspondence: MK Adjaloo, Technology Consultancy Centre, College of Engineering, KNUST, Kumasi, Ghana, Tel +233 243 136 701

Received: February 17, 2021 | Published: December 9, 2021

Citation: Adjaloo MK, Oduro WS, Ansah OE, et al. A comparative study of the reproductive success of Theobroma cacao L (malvaceae) under natural and manual pollination. Horticult Int J. 2021;5(5):192-200. DOI: 10.15406/hij.2021.05.00229

The reproductive successes under natural and manual pollination were assessed. Two cocoa farms around Bobiri Forest Reserve, in the Ejisu-Juabeng District Ghana were purposively selected. Fifteen percent of open flowers from five selected cocoa trees were subjected to manual-pollination and total exclusion. Ninety pods under natural pollination were compared with ninety pods under manually pollination. Proximate analysis was carried out to evaluate the macronutrients of cocoa pod and seeds produced under the two pollination modes. Results show that pollinator exclusion significantly decreased fruit set (df=2, X2 =12.5, P=0.00) and flower set (df= 2, F=25.2, P=0.00) (P=0.00). Pod weights and seed numbers significantly differed (V=0.049, F (4.49)=0.986, p<0.01, eta squared=0.049) irrespective of pod size and mode of pollination, however, there were individual differences. Weights of small pods did not differ (p>0.05) under the two pollination regimes, however, weights of medium size pods (p < 0.05) and that of the large pods (<0.05) produced under the two regimes of pollination differed. Number of beans and the size of pods did not differ under the two modes of pollination. Linear relationship existed between weight (y) and seed number (x) of individual pods: Y=18.56 + 0.016x; R2=0.45. Macronutrients of pods and seeds did not differ (paired t test= 4.08, 29 d. f.; P=0.12) under the two pollination mode. The study concluded that natural pollination contributed to cocoa production.

Keywords: cocoa pods, forcipomyia spp, midges, natural/manual-pollination, theobroma cacao

Cocoa (Theobroma cacao L. 1759), is a major economic resource to several tropical countries.1,2 An estimated seventy percent of the world’s cocoa is produced in West Africa which is described as the hub of cocoa cultivation.3 Cocoa accounted for about 40% of the total exports of Ghana in the year 2004,4 and contributed as the largest export for the country.5 It has therefore been classified as a commodity crop.

Even though the economic importance of cocoa is globally acknowledged, very little is known about the factors that determine its yield.6 Some authors believe that cocoa is among crops whose production largely depends on insect pollinators,7,8 yet the natural pollination of cocoa is poorly studied and has been largely ignored. This is so because the determinants of cocoa yield are often attributed to other factors such as payment of remunerative producer prices, quality of planting materials,9 use of pesticides and fertilizers(Winder J.A. unpublished).Since pollination is viewed as a “fundamental process in almost all productive terrestrial ecosystems” (Klein et al. 2008), further studies of the natural pollination of cocoa could contribute substantially to the understanding of cocoa production10 and help in the management of its pollination system (Kevan,1977).

Theobroma cacaoL. is a cauliflorous tree and produces, like many other tropical plants, a surplus of flowers. Cocoa bears hermaphrodite, homogamous flowers.11 The anthers are covered by elongated petals arranged in a concave form. The ovary is surrounded by infertile staminodes. Such complex flower structure requires the participation of insects for pollination.12 The arrangement represents an adaptation of T.cacao to the activity of its main pollinator agent, Forcipomyia species.13 It is believed that the coloured flower parts, especially the petal guidelines and the staminodes attract the midges.14 Cocoa’s reproductive biology is characterized by very low fruit-set, with no more than 5% of flowers developing into mature fruits.6,12 Some authors15,16 have observed that natural pollination can be increased up to 10 fold by manual pollen supplementation, but this needs to be established.

Natural pollination is often overlooked but at a large cost factor in crop production. There are recorded instances of pollination deficit reducing agricultural productivity.17 In case of poor pollination, costly techniques, such as manual (manual or artificial) pollination, is applied to enforce fruit set and often with poor results.18 Fortunately, there is a global concern for pollinator decline and this has resulted in more global studies, in recent times.19-23 To date, however, most of the studies on natural pollination were done between 1950’s - 1970’s, consequently, contemporary information on the subject is very scanty. There is therefore the need for more studies to update information on cocoa pollination and its practical relevance for the benefit of the cocoa farmers who are the actual producers of the country’s cocoa. To ensure the availability of desired cocoa seeds for farmers each year during the cocoa planting season, the Cocoa Research Institute of Ghana (CRIG) through its Seed Production Units (SPUs) in all the cocoa growing areas of Ghana, have adopted artificial (or supplementary manual) pollination, but there has not been any proper assessment of this mode of the crop’s reproduction.

Against this background a study was carried out to compare there productive success of cocoa under the natural pollination with that of the manual pollination using the number of seeds per pod and weight of pod as measures of reproductive success.24 Various authors have shown that pollination effectiveness is manifested in the number of seeds as well as the weight of crops.25-29 This study attempts to answer the question whether the reproductive success of cocoa under the natural pollination is different from that under the manual pollination by responding to the following specific questions:

The study, however, commenced with a pollination exclusion experiment to confirm if pollination as a limiting factor in cocoa production and concluded with proximate analysis of the cocoa pods produced. The result is vital for overall production of the crop, and is expected to rekindle some interest in cocoa pollination and ultimately, encourage its integration into agricultural extension protocols.

The study area

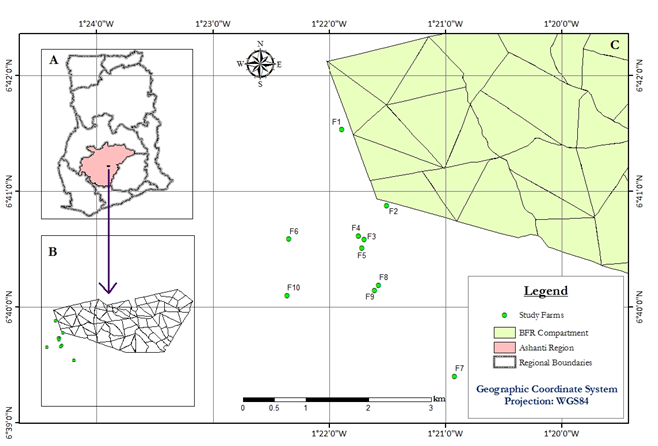

The study was carried out in two small holder cocoa farms (Figure 1; Table 1) around the Bobiri Forest Reserve, situated in the Ejisu-Juabeng District, in the Ashanti Region of Ghana. The Forest Reserve covers about 54.6 km2and belongs to the Triplochiton-Celtis Association of the Tropical Moist Semi-Deciduous Formation, the South East Subtype.30 The area lies between 67. Latitudes 60 44’ and 6040’ North and longitudes 1015’ and 1022’ West (source: Gold Coast Survey Field Sheet No.129), and is about 180 to 240m above sea level. The annual average temperature is 26.5 (± 1.44) OC, which combines with relative humidity of 86.1 (± 3.55) % and a mean monthly rainfall ranging between 19.1-235.1mm to produce a congenial atmosphere for the ecosystem. There are two rainy seasons: the major season (April to July) and the minor season (August to October) with the peak of rainfall in the month of June. This has resulted in clear seasonal fluctuations of wet and dry seasons, but there may be short, dry periods when rain does not fall. The climate is marked by high incidence of solar radiation.

Figure 1 Map of Ghana (A) showing Study Area (B) and location of of farms in relation to the Bobiri Forest Reserve (C).

|

Farm Plot (400m2) |

Distance from the Forest (m) |

Size of Farm (ha) |

Percentage of Cocoa Variety |

|

|

|

Amazon Hybrid |

|||

|

1 |

1,730 |

0.9 |

75 25 |

|

|

2 |

670 |

0.6 |

60 40 |

|

Table 1 Profile of the Study Farms

The two farms selected for the study were of sizes 0.6 and 0.9 ha, located at different distances from the Forest Reserve. Both farms had mixtures of hybrid and Upper Amazon cocoa varieties; and the Amazon cocoa was dominant in numbers. The study trees aged between 20 and 25 years were sampled within a standard plot of 400m2 (20m x 20m) of each farm (Table 1).

Pollinator-exclusion study:

A pollinator-exclusion experiment spanning over six consecutive weeks was carried out in the rainy season (May-June) in 2011 and repeated in 2012. The purpose was to confirm whether pollination is a limiting factor for cocoa production, and thereby determine the potential for autonomous self-pollination. Though pollination exclusion experiment had been conducted in South American countries (there is no record such study carried out in Ghana and Africa. Five cocoa trees bearing mature floral buds about to undergo anthesis in 24 hours were purposively sampled. Two treatment regimes were carried out: manual pollination; and total exclusion of pollinators.

Due to their cauliflory cocoa trees produce flowers both on the trunks and on secondary branches, therefore in this study flowers that were within hand- height (1.5-2 m) were subjected to the two treatments, as flowers above 2 m were out of reach. The hand-height is the protocol of the Cocoa Research Institute of Ghana.31 Each week fifteen percent of mature floral buds per tree were randomly selected, allowed to flower and subjected to treatment. Fresh, open flowers of three different non-experimental trees were collected as pollen donors. An open anther from each of these flowers was rubbed against the stigma of the flower to be pollinated. Pollination was done once per flower, ensuring that pollen grains were deposited, hence enhancing the likelihood of fruit set.32 Flowers thus pollinated were marked using clear plastic strips indicating the pollination date, attached to the bark by a pin, while the remaining unpollinated open flowers were removed. Total exclusion of pollinators was done using pollinator-exclusion tubes. These tubes had fine (1 mm) nylon mesh covering the anterior, while the posterior was stuck in a gummy material applied around the flowers, on the stem of the cocoa. The procedure was repeated every week. Pollination success was measured by two pre-maturity parameters of yield: Flower set (indicating successful pollination) and fruit set (evidenced by cherelle formation). The flower set was characterized by slight increase in purple coloration in the petals and sepals after 24 hours coupled with drying of the sepals which completed within 36 hours. The number of flowers that were pollinated could be censored. Cherelle formation was counted every 48h.

Natural pollination (NP) versus the artificial pollination (AP)

Cocoa pods (fruits) produced under natural pollination were compared with those of manual pollination conditions. The purpose was to determine whether there was any significant difference in the reproductive success using the weight of and number of seeds in the pods (fruits). The cocoa trees for the study were also selected by simple random sampling. Trees on each plot were first counted and numbered. The numbers were recorded on paper slips and placed in a bowl. The slips were drawn randomly without replacement, avoiding any bias, and the number on it indicated the tree to be tagged for the study. Thus, a total of sixty (60) flower-bearing cocoa trees were selected through systematic sampling from Farm plots 1 and 2. These trees were marked for identification. Thirty (30) of them were manually pollinated as described above in the month of May 2012, while the other thirty was left for natural pollination. A total of ninety (90) mature fruits made up of small fruits (5-10 cm), medium (11-60 cm), and large (>60 cm) fruits produced under natural pollination were randomly selected and harvested from the cocoa trees. The cocoa trees usually produce different sizes of pods, so these categorized (longitudinally measured) sizes of cocoa pods were common under the two pollination regimes. All were weighed with the help of manual balance in grams/kilograms, and the seeds counted. Similarly, 90 mature fruits produced through the manual pollination were randomly selected. The entire experiment was repeated within the same months in the year 2013 to validate the results.

Proximate analysis

Randomly selected seeds and pods under the two modes of pollination were subjected to proximate analysis using the Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC, 2010) method was carried out at the Department of Biochemistry, of Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology to determine whether there is any difference in the different macronutrients in the cocoa pod and seeds produced under the two pollination regimes. The analysis covered determination of moisture content, crude fat, crude fibre, ash, protein, and total carbohydrate:

Determination of moisture content

Five (5) grams of sample was transferred to previously dried and weighed dish and placed in an oven thermostatically controlled at 105oC for 5hr.It was then removed and placed in a desiccator to cool to room temperature and weighed. This was repeated till a constant weight was achieved.

Determination of crude fat and crude fibre

250ml round bottom flask was weighed after drying in an air oven at 100oC. Five (5) grams of sample was transferred to 22x 80mm paper thimble and a ball of cotton wool was placed into the thimble to prevent loss of the sample. About 150ml of petroleum spirit B.P. 60-80oC was added to the round bottom flask. Extraction was then carried out in a Soxhlet after which the thimble was removed to recover the solvent by distillation. The flask and the fat (oil) were heated for 30min in an oven at103oC. These were cooled to room temperature in a desiccator. The weight of the fat collected was determined after weighing the flask. Crude fibre was reported as loss in weight on ignition of dry residue remaining after digesting the sample with 1.25% H2SO4 and 1.25% NAOH.

Determination of ash

Two grams of sample was placed into a crucible which had been previously ignited and cooled, and then weighed. The crucible (and its content) was ignited in a muffle furnace (pre-heated to 600oC) for 2hr. It was then removed, cooled in a desiccator and weighed.

Determination of protein

The protein content was determined by the Kjeldahl method. Five gram sample was heated in sulphuric acid in the presence of selenium-based catalyst tablets and a few anti-bumping agents. This was digested till carbon and hydrogen are oxidised, as the protein nitrogen was reduced and transformed into ammonium sulphate. Sodium hydroxide was added and the digest heated to drive off the liberated ammonia into a volume of standard acid solution. The unreacted acid was determined and by calculation the percentage nitrogen in the organic sample was determined. A conversion factor of 6.25 (equivalent of 16% Nitrogen per gram of protein) was used.

Determination of total carbohydrate

The total carbohydrate was determined as the difference between 100 and the sum values of the moisture, crude protein, and crude fat, crude fibre and ash contents in sample.

Data analysis

Pollinator exclusion experiment

The pollen limitation was calculated using Larson-Barrettindex (Larson and Barrett, 2000) as follows: [L=1-(Po/Ps)], where:

Pois the percentage of fruit set taken from open-pollinated controls;

Psis the percent fruit set by plants that were artificially pollinated;

L=0 indicates no pollen limitation in the population under study.

Per cent fruit set was used as the measure of fertility as pollen limitation has been reported most often in terms of fruit set.33

Reproductive success under natural pollination and artificial pollination

To investigate whether there were differences in the reproductive success, measured by the weight and number of beans of cocoa pod, depend on the nature of pollination method, a one-way multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted to determine whether each of the two mode of pollination (manual and natural) influenced simultaneously, the weight and number of beans of cocoa pods. Prior to the data analysis, MANOVA assumptions i.e. independence, multivariate normality, homogeneity of variance-covariance matrices were thoroughly examined. Since some of the MANOVA assumptions (particularly homogeneity of variance-covariance) were violated the Pillai-Bartlett’s Trace omnibus test was used.

A Pearson’s chi-square test of independence was conducted to determine whether the sizes of pods affected the number of seeds in the pods irrespective of the pollination regime. The Pearson’s chi-square test of independence was used to determine the significant difference or relationship between two variables. The frequency of one variable was compared with different values of the second variable. The null and alternate hypotheses were stated below:

H0: There is no significant difference between two variables

H1: There is significant difference between two variables

All analysis were done using R. Studio version (3.2.4), 2016 programme and were considered at an overall significance level of P= 0.05.

Proximate analysis

The moisture content was obtained by measuring the loss of weight after drying the samples,. and expressed as percentage moisture given by:%moisture =

Fat content was expressed as a percentage by weight:% FAT= ; where:

A = amount of fat in the sample,

M= mass of the sample

Crude Fibre was given by: % Crude Fibre = ;

The protein is calculated as percentage given by: % Protein = F x % N;where:

F = a conversion factor of 6.25 (equivalent of 16% nitrogen per gram of protein)

%N = percentage nitrogen obtained from sample.

Total ash is determined by: % Ash = ;

Carbohydrate was analysed as stated above.

The results of samples from the two regimes were compared using paired t test.

Pollinator exclusion experiment

The exclusion of pollinators caused a significant decrease in fruit set (d.f. = 2, X2 =12.5, P = 0.00), flower set (d.f.= 2, F=25.2, P=0.00) compared to trees that experienced under the manual pollination. All the flowers that were covered and thus un-pollinated dropped in batches between the second and third days. The calculated value of pollen limitation index [L=1-(Po/Ps)] was L= 0.593.

Reproductive success under natural pollination and artificial pollination

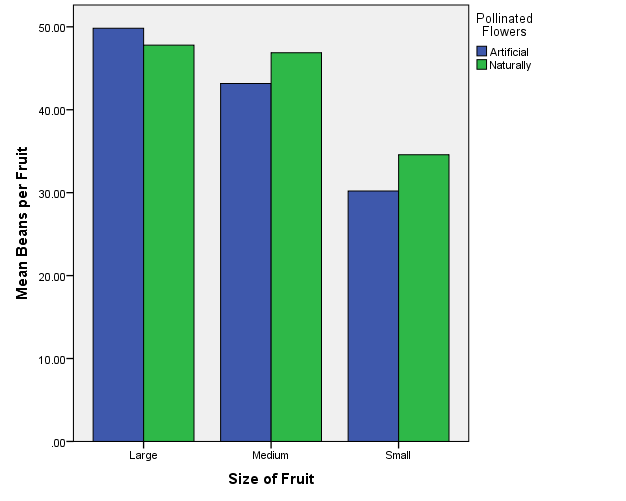

A summary of the omnibus Pillai’s trace multivariate test of the effect of mode of pollination and fruit size and their interaction on yield is given in Table 2. The omnibus Pillai’s trace values (V=0.049, F (4.49) = 0.986, p < 0.01, eta squared = 0.049) indicated that the pod weight and number of seeds significantly varied simultaneously across the two main effects (mode of pollination and size of cocoa pods), and their interaction (i.e. reproductive success in mode of pollination) was significantly influenced by the pod size. This indicates that the combined dependent variables differed, on average, between natural and manual pollination, between pod size (small, medium, and large), and also their interactions. The partial eta squared values suggest a stronger pod size effect than both mode of pollination and interaction (Table 2). However, the mean weights of pods appeared to be marginally higher in medium and large sizes under the natural pollination(Figure 2). The mean number of beans of pods also appeared to be marginally higher in medium and small sizes under natural pollination (Figure 3).

|

Effect |

Value |

Hypothesis |

Error |

F |

P |

Partial Eta |

|

Pollination Mode |

0.049 |

2 |

173 |

4.491 |

0.013 |

0.049 |

|

Fruit Size |

0.863 |

4 |

348 |

66.008 |

0 |

0.431 |

|

Interaction |

0.104 |

4 |

348 |

4.769 |

0.001 |

0.052 |

|

2 |

670 |

0.6 |

60 |

40 |

Table 2 Pillai’s trace multivariate test of the effect of mode of pollination, fruit size and their interaction on yields

Figure 3 A cluster bar plot of mean number of beans against pod sizes for the two modes of pollination.

After the establishment of the differences in natural and manual pollination separate ANOVAs were conducted on each of the dependent variables to establish the actual differences. The weight of small pods under natural pollination was compared with that of manual pollination. The same was done for medium and large pods. There was no significant difference (p > 0.05) between the weights of small pods produced under the two pollination regimes. However, there were significant differences between the weights of medium size pods (p < 0.05) and that of the large pods (<0.05) produced under the two regimes pollination (Table 3).

|

Pod Sizes |

Natural Pollination |

Manual Pollination |

P-value |

|

Small |

409.3±9.14SE |

387.3 ±8.36SE |

0.28 |

|

Medium |

730.7±11.92 S.E. |

659.3±8.85S.E. |

0.03 |

|

Large |

1003±12.52SE |

893±10.02S.E |

0 |

Table 3 Weight (g) of pods under the Two Pollination regimes

The number of seeds in small pods under natural pollination and manual pollination conditions differed significantly (p<0.05), and this applied to the medium sized pods p< 0.05; however, there was no significant difference in the number of seeds of large pod sizes under the two modes of pollination (p > 0.05) (Table 4).

|

Pod Sizes |

Natural Pollination |

Manual Pollination |

P-value |

|

Small |

36.47 ± 11.22 SE |

28.20 ± 7.94 SE |

0 |

|

Medium |

43.97 ± 4.67 SE |

39.60 ± 6.69 SE |

0 |

|

Large |

46.47 ±5.56 SE |

44.97± 5.27 SE |

0.22 |

Table 4 Number of seeds pods under the Two Pollination regimes

From the Pearson’s chi-square test of independence there was no significant difference between the number of seeds and the size of pods irrespective of the mode of pollination (Table 5). A regression analysis showed a significant linear relationship between weight (y) and seed number (x) of individual pods: Y =18.56 + 0.016x; R2 =0.45.The number of seeds per cocoa pod was related to the weight of the pods, with the aim of estimating cocoa beans from the pod. The number of beans per pod fairly increased with increasing pod weight (Figure 4).

|

Pod sizes interactions |

Natural |

P-value |

Manual |

P-value |

|

Small-medium |

X-squared = 318.08, df = 304 |

0.28 |

X-squared = 266.67, df = 255 |

0.2952 |

|

Small-Large |

X-squared = 290, df = 285 |

0.41 |

X-squared = 243.33, df = 225, |

0.1913 |

|

Large-Medium |

X-squared = 231.08, df = 240 |

0.65 |

X-squared = 260.83, df = 255 |

0.3875 |

Table 5 Effect of pod sizes on the number of seeds under the two mode of Pollination

The relationship could be represented by the Michaelis-Menten expression (cf. Jorgensen and Faith, 2011) as:

Bn = (66.26 x Pw) x (375.4 +Pw)-1 (R2 = 0.4532; rmse = 7.337; n = 360)

Where;

Bn: Number of beans per pod

Pw: Weight of the pod (g)

66.26: The extent of increase in the number of beans per weight of cocoa pod (Standard error of estimate (SE) is ±2.67)

375: A measure of maximum number of seeds in a pod (SE = ±41.67)

rmse: Root mean square error.

The significance of the model is that at smaller pod weight, the number of beans in a pod is proportional to the weight of the pod. However, as the weight of the pod continues to increase the number of beans that a pod could contain approaches a maximum and constant value.

Proximate analysis

A proximate analysis method revealed that the food constituents were common in pods produced under the two pollination regimes (Table 4). Pod by pod the moisture and fat content of the naturally pollinated pod was lower than the manually pollinated, but the protein, fiber, ash and carbohydrate of the naturally pollinated pods were higher. On the other manual, apart from the moisture content of the naturally pollinated seeds which was of higher value all other constituents were lower than the artificially pollinated pods. On the whole, there was no significant difference (paired t test= 4.08, 29 d. f.; P = 0.12) between the macronutrients of pods under the natural pollination and those under the manual.

|

Parameter |

Natural pollination |

Artificial pollination |

Method |

||

|

% |

Pod |

Seed |

Pod |

Seed |

|

|

Moisture |

73.3 |

49.17 |

79.62 |

40.65 |

AOAC* |

|

Fat |

0.08 |

5.12 |

0.11 |

3.94 |

AOAC |

|

Protein |

1.86 |

9.8 |

1.32 |

8.32 |

AOAC |

|

Fibre |

0.21 |

22.64 |

6.48 |

17.61 |

AOAC |

|

Ash |

1.6 |

1.5 |

1.25 |

19.17 |

AOAC |

|

Carbohydrate |

15.95 |

19.01 |

11.22 |

18.17 |

AOAC |

Table 6 Proximate Analysis of Cocoa Pods and Seeds of Natural and Artificial Pollination

Results quoted on wet basis

Pollinator exclusion experiment

The study suggested that the exclusion of pollinators resulted in pollen limitation (index [L=1-(Po/Ps)] was 0.583), which manifested in reduced pod set as well as flower set. Data therefore demonstrated that pollination was a limiting factor in cocoa production. Larson and Barrett (2000) had noted that self-incompatible angiosperms generally have higher pollen limitation index (L= 0.59) and this indicates their dependence on cross-pollination by pollinators. Conversely, self-compatibility and autogamy are associated with reduced pollen limitation, as their capacity for self-fertilization decreases their reliance on cross-pollination by pollinators. The Amazon cocoa studied was self-incompatible and therefore needed an external agency for the sustenance of its reproductive system, and lacks the potential for autonomous self-pollination. The results therefore corroborates an earlier assertion that cocoa is strictly entomophilous,7,8 and necessarily requires insect pollinators.24,34,35 According to Efron36 cocoa production involves several different stages starting with flowering, followed by pollination, cherelle and pod development and ending with mature ripe pods. Pod set is the stage of flower-to-pod survivorship at which plants match the number of pollinated flowers with resources available for pod maturation.37 Therefore pollination success is largely determined by the initial levels of pod-set.38 Adjaloo et al (2012) observed that the higher the levels of successful pollination indicated by flower set, the greater the pod set (cherelle), indicating a positive relationship between the two prematurity parameters of yield.

Pollination in cocoa has been evaluated to be a higher order limiting factor in cocoa reproductive success.8 Ashman33 attributed pollen limitation in plants to floral phenotype, presence of co-flowering plant species, decreases in plant population size/density and pollinator decline. Plants pollinated by biotic pollinators are usually considered to be more specialized than those pollinated by abiotic vectors.24 Such specialization may provide more reliable pollination, resulting in lower levels of pollen limitation. The result therefore is instructive as it underscores the need to ensure the presence of adequate pollinators of cocoa.

Natural verses artificial pollination

Generally, the number of seeds produced under natural pollination was more than those of the artificially pollinated as demonstrated by the results. This might be explained in terms of unrestrained access of pollinators to the cocoa flowers under the natural conditions. Data also suggested that both small and medium sized pods differed under the two modes of pollination, however, number of seeds of large pods were not (Table 4). The flowers of the cocoa trees studied might have received unlimited number of pollinating insects under the natural pollination, thus resulting in pollinator effectiveness.27 This could result in pollination intensity25 i.e. the number of conspecific pollen grains deposited onto the stigma during the pollination process. It could determine the number and size of pollen load deposited per stigma, and hence, the seed number per pod. Some authors26,28 investigating the reproduction in angiosperms have linked the number of pollen grains per stigma to the production of fruits and seeds. It could be that as the number of compatible microgametophytes (both the pollen grains and tubes) increases, seed set also increases26 thus, the genetic composition of pollen load could determine the number and size of seeds produced per fruit. The data obtained in the study confirmed this. Alternatively, the results may be due to adequate deposition of pollen by the individual pollinators during a visit. Even though the rate of visiting same flower by one or more pollinators has not been assessed, it is possible that the high number of cocoa flowers produced at a time might limit multiple visits. Should that hold then the midges which have evolved with the flower is able to probably deposit adequate pollen on a single visit as suggested.39 Earlier studies8,16,27 have demonstrated that there is a positive relationship between pollination intensity(i.e. the number of pollen grains deposited onto the stigma during the pollination process)and the number of seeds per pod. Reproduction studies in angiosperms also indicate a link between the number of pollen grains per stigma and the production of pods and seeds.31,40 The number of compatible microgametophytes (the pollen grains and tubes) increases with seed set.31 Therefore, the genetic composition of pollen load could determine the number of seeds produced per pod. The results obtained in this study agree with this observation.

While the the mean weight of small pods did not differ irrespective of the mode of pollination, weights of the medium and large pods were different under the two regimes. Again weights of pods under the naturally pollinated fruits were higher than the manually pollinated. Fruit weight has been found to increase with increasing pollen load in crops such as cashew26,29,41 and coffee42,43 due to an increase in growth rate. The results seem to agree with the proposition that there is some relationship between the number of seed produced and weight of crops.44,45 Other authors.8,46 have also indicated that the weight of individual cocoa pod might be determined by the number of pods per tree at a time, because the available nutrients regulate the pods production. High number of flowers increases the probability of obtaining more pods, however, the number of pods harvested depends on post-flowering events (pollination, cherelle wilt and pod/pod losses), and the underlying factor is the availability of nutrients. During the period of study it was observed that 80% of pods were small sized. While this could be attributed to characteristics of the Amazon cocoa variety found in the study area, it underscores the fact that weight of pods is limited by the availability of nutrients.

The fact that there was no difference between the number of seeds and pod sizes irrespective of the mode of pollination may be explained in terms of variations during the pollination of the cocoa flowers.27 This study, however, did not cover this process and is recommended for further investigation in the case of cocoa. The data also suggested that there was no correlation between the weight of the cocoa pods and the sizes of pods. It implies that perhaps the weight of cocoa pod could be dependent on other factors. Though the precise relationship between the pod weight and the pod sizes of cocoa may not be known, given the fact that there is some relationship between the weight of fruits of crops and the number of seeds in the pod, and in view of the fact that the number of seeds per pod affects the rate of fruit growth, it could be inferred that some relationship could exist as in other crops.28,44

The linear relationship between the weight of pod and the number of seeds of individual pods found in the small pods as demonstrated by the model might be due to the fact that higher seed numbers could increase the rate of fruit growth at the early stage of its development.44,47 However, the number of seeds reaches a maximum and constant value as it might be limited by the number of pollen grains deposited at a time (Figure 4). Brew31 indicated that the cocoa pollinators deposit up to 60 pollen grains per stigma. If so the cocoa pod may contain up to this number of seeds notwithstanding the weight.

As expected the proximate analysis (Table 5) suggests that the food nutrients in fruits produced under the two pollination regimes are the same. The results therefore suggest that both manual and natural pollination of cocoa contribute to the productivity and therefore the overall production of cocoa. This study is of global essence. Manual pollination may be undertaken by plant breeders in research organizations primarily to develop new varieties of crop. In such cases manual pollination has the advantage over natural pollination in that the growers can choose the parent plant stock and decide whether to pollinate the plant with its own pollen (selfing) or with pollen of a different plant of the same species (cross pollination) even with another species (hybridizing). Farmers do not have the manual pollination technology, and, with the poverty level they would not be able to cope with the cost implications. Moreover, employing manual pollination in larger farms could be tedious and near impossible. The results therefore suggest that natural pollination should be encouraged in the cocoa cultivation and be part of the protocols of extension workers.

The study has demonstrated that natural pollination contributes to the productivity and therefore the overall production of cocoa. To enhance this mode of pollination there is the need to create the suitable environment for the pollinators. The flowering pattern of the cocoa tree suggests the need to encourage natural pollination. Studies have been done demonstrating that plantain/banana substrate or a mixture with cocoa pod husks could provide the right environment for the pollinators. Natural pollination is cheap. Manual pollination is limiting as it is done within a range of the hand height leaving most of the flowers on the canopy unattended to. On the otherhand. manual pollination has some advantage over natural pollination as it may be employed to develop new varieties of crop. Since farmers do not have the artificial pollination technique, and cannot cope with the cost implications natural pollination should be encouraged in the cocoa cultivation. The knowledge from this study therefore can constitute the basis for the promotion of farm practices that enhance the conservation of cocoa pollinators in order to promote crop yield.

The study concluded that natural pollination could result in increased seed production and weight of cocoa pods and therefore it could contribute to the productivity and therefore the overall production of cocoa. Also the food nutrients in fruits produced under the two pollination regimes are the same. The study recognizes that the rate of visiting same flower by one or more pollinators has not been assessed. It is therefore recommended that future study of natural pollination should include the frequency of pollinator visitation and fruit set. It is also recommended that the effect of higher seed numbers on the rate of fruit growth at the early stage of cocoa’s development should be studied.

This study was carried out through the assistance of the Ghana Government and by World Bank Funding through the TALIF Project. The authors are very grateful to Mr Ato Harry Brew, a retired Cocoa Entomologist of the Cocoa Research Institute of Ghana, whose guidance made the study possible. Dr Moses Mochiaa and Dr Michael Achiaw of Entomology Section of the Crops Research Institute, Council for Scientific and industrial Research read through the manuscript.

©2021 Adjaloo, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.