eISSN: 2373-6372

Research Article Volume 10 Issue 6

Department of Internal Medicine/Gastroenterology, Wayne State University School of Medicine, USA

Correspondence: Paul H Naylor, PhD, 6938 Hudson Bldg, Harper University Hospital, 3990 John R, Detroit, MI 48201, USA

Received: November 18, 2019 | Published: December 26, 2019

Citation: Abu-Heija A, Mohamad B, Tama M, et al. Using the endoscopy suite of an urban medical center for efficient identification of patients with HCV and linkage to care. Gastroenterol Hepatol Open Access. 2019;10(6):319-322 DOI: 10.15406/ghoa.2019.10.00403

Introduction: Since cancer screening by colonoscopy is recommended for patients in a similar age cohort as recommended for HCV screening, we tested the hypothesis that determining the HCV status of colonoscopy patients in an open access primarily African American (AA) endoscopy suite, could yield an increase in the number of patients identified with HCV infection and subsequently linked to care.

Methods: Colonoscopy patients in the HCV age cohort seen in 2014 (n=444) and 2017 (n=544) ) were evaluated determine if patients were tested for HCV and the result of the test.

Results: The patients were 75% AA and the percentage with an antibody test was 32% in 2014 and 43% in 2017. If tested, the HCV antibody positive rate was high (43% and 32% respectively). AA patients in 2014 were more likely to be positive than non-AA individuals (49% vs 24%) as compared to 2017 (32% vs 30%). Only half of the HCV positive patients were treated or were pending treatment (2014=59%; 2017=52%).

Conclusions: This study confirmed that testing for HCV in colonoscopy patients in a high AA population center can identify significant number of patients who have not been tested and/or treated for HCV.

Keywords: HCV screening, colonoscopy, hepatocellular carcinoma, chronic hepatitis C, primary care physicians

Abbreviations: HCV, hepatitis C virus; AA, African Americans; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; PCPs, primary care physicians, EMR, electronic medical records; GI, gastroenterology; UPG, University Physician Group; ID, infectious diseases

Three million Americans are estimated to be infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV), with twice the seroprevalence in African Americans (AA) as compared to Caucasians.1–4 Chronic hepatitis C can lead to cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and death with AA having higher HCC and mortality rates than Caucasians. With cure rates using direct acting anti-virals approaching 100%, optimizing strategies to identify patients with HCV and link them to care would be expected to pay high dividends with respect to public health.

Since 60-75% of HCV infected adults were born between 1946 and 1965 (current age of 72 to 52), the Preventative Services Task Force recommends one-time screening of all individuals in this birth cohort, regardless of risk factors.5–10 This mandate for screening falls mainly on primary care providers for this baby boomer cohort but has been less effective than desired (13.8% had been tested by 2015) and subsequent linkage to care has been underwhelming.5,8 This less than effective screening and likeage to care may be due to the complexity of referring patients to gastroenterologists in high volume HCV treatment settings and ensuring that the patient is seen. In light of the modest increase in cohort screening, it remains to be determined whether additional screening settings outside of primary care physicians (PCPs) might be useful.

Patients attaining the age of 50 should have periodic screening colonoscopies. It is possible that identifying HCV patients who have not been treated in a setting rich in such patients is an underappreciated option for identification and linkage to care.11 The objective of this study was to assess the rate of HCV positive patients who would be identified if screening for HCV were done in an open access colonoscopy suite with predominately AA patients. We also used the HCV patients identified in this retrospective study, to track lineage to care in this predominately AA population.

The Detroit Medical Center endoscopy electronic medical records (EMR) were used to identify patients born between 1945-1958 undergoing screening colonoscopy in 2014 or 2017. The two dates were selected to compare patients seen in an era where cohort screening was just beginning (2014) and a time when cohort screening should have been aggressively pursued (2017). The EMR was also used to determine whether HCV antibody testing had been performed at any time prior to the colonoscopy procedure by the DMC medical laboratories. AS expected for screening colonoscopies, there was no overlap of patients between the two time periods. If patients were positive, the Wayne State University Physician Group (UPG) EMR was used to determine whether the patients were seen either before or after the procedure through 2018. These patients were then used to assessment of linkage to care with gastroenterology (GI) or infectious diseases (ID) and to define treatment and response to treatment for HCV. Positive linkage to care was defined based on HCV positive patients who had at least one visit to a university-based physician following testing. Since this is an open access suite and patients were referred by physicians who were not in the University Physician Group and may not use the DMC laboratories, the study could not determine screening rates or results for patients who did not have their laboratory testing at DMC. Chart review and data collection was performed according to a Wayne State Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved protocol. The Wayne State University Institutional Review Board operates under United States Department of Human Services Federal Wide Assurance. Data analysis was performed using the JMP statistical program with student’s t-test for continuous variables and Pearson chi-square for character variables. Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05

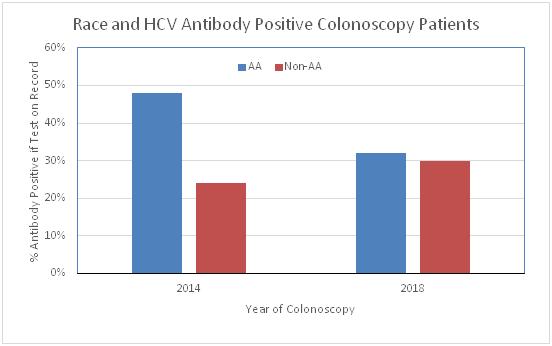

For the 2014 analysis, 444 age sequential cohort eligible patients beginning at age 74 were identified. The Medical Center Laboratory EMR was used to determine demographics; whether the patient was tested for HCV antibody and to calculate the HCV antibody positive rate for colonoscopy patients in the cohort age group (Table 1). The overall number of patients undergoing a colonoscopy who were tested for HCV was low (140/444= 32%) but if a patient was tested, the antibody positive rate was high (43%). As a comparison to more recent patients, the last 6 months of 2017 colonoscopies was searched to identify 544 colonoscopy patients who were HCV screening cohort eligible. When compared to 2014, only slightly more had been tested and if tested the positive rate was 32% (Table 1). When compared, the percent of patients tested was greater in 2017 as compared to 2014 (43% vs 32% p<0.005). When racial disparity was assessed with respect to antibody positivity, AA patients were more likely to be positive in the 2014 set of patients as compared to Non-AA (52/107=48.6% vs 8/33=24.2%, c2 p=0.013 Table 2, Figure 1). In contrast the distribution was similar in 2017 (54/169=32.0% vs 15/50=30.0%, c2 p=0.794). If HCV infection was verified by PCR testing, 95-96% was positive. Although there was no difference in the average age of patients in the two groups, there was a difference with respect to the relationship between the age of the individual and whether they were tested for HCV. In the earlier group of colonoscopy patient (2014) the older individuals were more likely to have been tested for HCV (p<0.005 Logistic fit) while in the more recent group of colonoscopy patients were the opposite was true (ie older patients were less likely to have been tested (logistic fit p<0.007)).

Figure 1 Rate of HCV antibody positivity in colonoscopy patients who were tested was compared for AA vs Non-AA in 2014 and 2017. Patients were all in the age cohort recommended for screening. The rate was higher in AA compared to Non-AA patients in 2014 (52/107=49% vs 8/33=24%, 2 p=0.013) but not in 2017 (54/169=32% vs 15/50=30%, 2 p=0.794). The % positive is on the y-axis and year on the x-axis. Significance was evaluated by Pearson Chi Square.

Year |

2014 (n= 444) |

2017 (n=544) |

p value |

Race (AA) |

317/444=712% |

430/544=79% |

p<0.006 |

Gender (Female) |

237/444=53% |

296/544=54% |

NS |

Age(years) (±SD)[Range] |

69.1(±2.2) [74-66] |

64.9(±3.6) 74-60] |

p<0.0001 |

% of Patients Tested for HCV |

140/444=32% |

219/544=43% |

P <0.005 |

Antibody Positive if Tested |

60/140=43% |

69/219=32% |

p<0.002 |

PCR Positive if Tested after Positive Antibody |

58/60= 95% |

55/57=967% |

NS |

Treated/Pending/On Treatment if HCV Positive |

34/58=59% |

35/67=52% |

NS |

Table 1 Comparison between Two Year Colonoacopy Cohorts: Demographics, HCV Testing Results and Linkage to Care

Year |

2014 (n= 444) |

p value |

2017 (n=544) |

p value |

||

Race |

AA (n=317 ) |

Non-AA (n= 127) |

AA (n=430 ) |

Non-AA (n=114 ) |

||

Gender (Female) |

181/317=57% |

56/127=44% |

p< 0.02 |

240/430=56% |

56/114=49% |

NS |

Age (±SD) |

69.6 (±2.1) |

69.8 (±2.4) |

NS |

65.5 (±3.6) |

65.4 (±3.4) |

NS |

% of Patients Tested for HCV |

107/317=34% |

33/127=26% |

NS |

168/429=40% |

50/114=44% |

NS |

Positive if Tested |

52/107=49% |

8/33=24% |

p<0.02 |

54/169=32% |

15/50=30% |

NS |

PCR Positive if Antibody positive |

49/52=94% |

8/8=100% |

43/44=98% |

12/13=92% |

NS |

|

Table 2 Racial Differences in the Two Year Cohorts: Demographics and HCV Testing Results and Linkage to Care

Since many of the HCV positive patients had their care delivered through the University Physician Group Practice (UPG), it was possible to assess linkage to care for patients who had a positive diagnosis in the UPG (Table 3). Based on the EMR, 59% (34/58) of the patients in 2014 and 52% (35/67) of the patients in 2017 were treated, on treatment or pending treatment as of December 31, 2018. If a patient completed treatment, the viral clearance (SVR) was 100%. In 2014, 75% of patients had at least one visit to GI or ID, in contrast to 2017 when only 60% of the positive patients had at least one visit to GI or ID to assess their status. With respect to the patients who did not have a visit of record, it is not known whether they were seen and treated outside the University Physician Practice Group (UPG) plan. With respect to patients who had only one visit, they were advised to return for treatment discussions based on further tests but failed to return for a 2nd visit.

* |

N (60) |

% Total |

N (69) |

% Total |

|

Pending Treatment |

GI |

10 |

17% |

8 |

12% |

ID |

2 |

3% |

3 |

4% |

|

Treated (100% cure) |

GI |

19 |

32% |

14 |

20% |

ID |

3 |

5% |

10 |

14% |

|

PCR Negative (ie not infected) |

2 |

3% |

2 |

3% |

|

No UPG GI or ID Visit |

GI/ID |

15 |

25% |

27 |

39% |

One UPG GI or ID Visit |

GI/ID |

9 |

15% |

5 |

7% |

Total for % Treated |

|

34/58 |

59% |

35/67 |

52% |

Data through 2018; treating specialty GI- Gastroenterology; ID= Infectious Disease Physicians |

|||||

Table 3 Linkage To Care for HCV Antibody Positive Patients*

This study provides retrospective data that endoscopy suite HCV age cohort screening is a viable site for HCV screening. Not only is the colon cancer screening population is in the age cohort but the number of HCV positive patients is large. Also, unlike emergency rooms there are few repeat visits with respect to colon cancer screening patients. We also evaluated the linkage to care for HCV positive patients undergoing colon cancer screening colonoscopies to determine whether identifying patients and linking them to a gastroenterologist for care would provide another avenue for increasing treatment of known positive individuals. There was a low number of colon cancer screening patients who had been tested for HCV (30-40 %), but if they were tested the number of positive patients was high (32-42%). Based on these numbers, point of care testing of the untested patients could yield significant numbers of positive patients, especially if the endoscopy center like ours was in an urban setting with an AA dominant patient population.

There are only a few published manuscripts documenting the evaluation of HCV incidence in cancer screening colonoscopy patients. This may be due to the assumption that numbers will be small since patients may have already been tested by the primary care provider, the population being screened is health conscious and thus previously tested or negative, and that the busy nature of most endoscopy suite precludes screening protocols.12–15

Three relevant studies have offered anti-HCV testing to the birth cohort either at the time of screening colonoscopy or in GI clinics.2–4 While significant numbers of patients agreed to testing, in the sites (Canada, Texas, 5 East Coast US centers), few were positive, suggesting a low yield from the significant effort required to obtain patient consent and subsequent testing. 2–4 Of notable relevance to our studies, is that these studies were not performed totally in inner city settings with high AA populations where prevalence of HCV might be higher.

Our patient population allowed us to address the issue of screening results in AA vs Non-AA patients being seen in a cancer screening colonoscopy population. The data suggests a decline in the number of positive AA patients that would have been identified between 2014 and 2017, although there was no significant change in the percent of positive Non-AA patients. This decline is in a setting where the percent of patients being tested had increased and may reflect an increase in cohort-based screening post 2014 which would of course result in fewer positive patients than risk-based screening.16–18

There are two important limitations to this study. The open access nature of the colonoscopy suite meant that patients were being referred by physicians who may not use the DMC laboratory for their HCV testing and thus the percent screened for the whole population receiving colonoscopies may be higher than suggested by this study. The second limitation of the study is that the percentage of positive patients when tested may be high due to the use of risk-based screening by primary care physicians rather than age-based cohort screening. Regardless of these limitations, even if the entire group was tested and no additional positive patients were identified, the rate would still be 13% (129/988)

Linkage to care and subsequent treatment of patients who were identified as HCV infected due to testing either in the IM clinics or during hospitalization, was good (52-59%) but there is room for improvement. Identifying positive colonoscopy patients based solely on a test in the EMR would have provided an opportunity to refer significant numbers of patients to an HCV treatment evaluation visit. If point of care testing with a rapid antibody testing kit were also utilized to screen patients who did not know if they were previously screened, significant numbers of HCV positive individuals who have not been treated may also be identified. Furthermore, since the GI physicians who were performing the colon cancer screening for these positive patients are also experienced in HCV treatment, scheduling the patients at the time of colonoscopy could results in an improved in linkage to care and treatment rates.

Our data support using open access colonoscopy suites with significant AA populations to identify patients who are HCV positive but not yet treated. EMR screening should be coupled with point of care tests to identify significant numbers of untreated patients undergoing a colonoscopy. Thus, based on our data from this predominately AA population seen in an urban setting, cost justified screening programs can be recommended in this and similar settings.

None.

There are no conflicts of interest for any authors with respect to this project.

None.

©2019 Abu-Heija, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.