eISSN: 2469-2794

Review Article Volume 7 Issue 4

Nottingham Trent University United Kingdom, UK

Correspondence: Andrew O’Hagan, Senior Lecturer in Forensic Science, College of Science and Technology, Erasmus Darwin, Room 230, Nottingham Trent University, Clifton Lane, Nottingham, NG11 8NS, UK, Tel 07850875563

Received: July 16, 2019 | Published: July 23, 2019

Citation: O’Hagan A, McCormack S. To what extent has the United Kingdom law on psychoactive substances been successful? Forensic Res Criminol Int J.2019;7(4):176-183. DOI: 10.15406/frcij.2019.07.00284

This review examines the law in relation to psychoactive substances and investigating how dangerous they really are and how much the law is required, together with how its enforcement is really impacting on the number of arrests and convictions and its prevalence in prisons. The law that was enforced on the 26th May 2016 across the United Kingdom has been the subject of some criticism, due to questionable gaps within this law, making it difficult to secure convictions. The ‘blanket ban’ approach has too been questioned, due to its lack of success with other legislations. Whilst this is not the first time a law like this has been enforced, the UK’s approach to the global problem, may not be the answer, or if it is following/making the same mistakes other countries have made. The United Kingdom policing system is already under an immense amount of pressure, and whilst the problem on psychoactive substances is clear, the law is not. So, while UK police are enforcing this law, their conviction rates are ceasing to be parallel with the number of arrests. Drugs, classified under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971, are prominent in society, even almost fifty year after the legislation came into force. A new approach was adopted to overcome the problem with psychoactive substances, it will not be a surprise if they are too, just as prominent in later years to come.

Keywords: psychoactive substances, drugs, law, legal highs

The law on psychoactive substances came into force on the 26th May 2016, across the United Kingdom. Previous to this law, it was legal to produce, supply and possess psychoactive substances, also known as “legal highs”. Legal highs were made in an attempt to mimic the real effects of illegal drugs controlled under the Misuse of Drugs act 1971. However, due to alterations in their chemical structures, they by-passed the law on illegal drugs, thus making them “legal highs”. Before this act, psychoactive substances were able to be brought readily from ‘Head Shops’ from prices as low as £10 a gram, making them easily accessible to the younger generation and the poor. The term ‘psychoactive’ is very broad and covers a wide range of substances, however, it is not particularly easy to prove whether a substance is psychoactive or not. Additionally, many of these ‘psychoactive substances’ have never been tested before, and have the potential to be very dangerous, with the different combination of chemicals that are contained within them. Over the years, the number of risks associated with psychoactive substances has increased, alongside the number of deaths associated with them, and whilst the UK recognises it is a growing problem, the question is whether this ‘blanket ban’ is really the answer. The new law is a ‘blanket ban’ approach; which is a complete ban that is aimed at covering all areas of an intended substance. The approach is aimed at reducing the availability and thus the use of the drug.

However, the UK will not criminalise people for personal use, its aim is to reduce how readily available it is by closing down ‘headshops’ and making importing, exporting and street sales illegal. In most cases, when a new law is enforced, you expect to see results within a certain amount of time, and it is from these results, that we can conclude how effective the law actually is. However, almost 2years on, the law is still by no means perfect. Therefore, throughout this report, there will be an exploration into the flaws of this law and why these flaws have not been reviewed and addressed. With the new powers of the police, and the number of arrests/offences increasing, you would expect to see similar results for the number of convictions. Yet, there are still discrepancies in what we expect to see, and what the reality is. Psychoactive substances are dominating prisoners’ choice of drugs and have been for quite some time now. But psychoactive substances are already banned in custodial institutions, so it is unclear as to how this act will make any difference on the number of prisoners using and dying from them. Psychoactive substances are a global issue, and the UK is not the first country to make an attempt at eradicating the problem. A diverse range of approaches have been attempted by Ireland, Poland, Portugal and the Czech Republic; however, it is unclear which approach to the law is best to deal with the problem if any. Whilst there is no definitive answer on the matter in question, further analysis of this law should raise awareness of the flaws within the law, thus allowing individuals to draw more informed conclusions regarding this issue.

Psychoactive substance

“A psychoactive substance is defined as any substance which:

Psychoactive substances are generally sold in foil packets and can be purchased on the web for £3-4 and sold at a street value of around £10-15. In prisons, it can retail at approximately 3x the street value.4 It is for this reason that psychoactive substances are becoming more popular and preferential than the original drugs they were intending to imitate, as they are a lot cheaper to buy in comparison (Figure 1).

The packing of these psychoactive substances usually comes with a warning stating that they are not fit for human consumption. However, this statement is contradicted by another warning, which states the toxic symptoms, which are a result of human consumption. The symptoms can include vomiting, nausea, diarrhoea, sweating, panic, headaches and restlessness. Additionally, the substances, which are intended as a plant food substitute, are sold in flavours such as ‘bubblegum’, and ‘cherry bomb’, which could be deemed illogical as such flavours are unnecessary for plants.5 Therefore, highlights its intentions to encourage and entice human consumption. NPS’s are typically synthetic drugs, although they also can be semi-synthetic. They usually come in forms of generations. A first-generation drug is the first one to show the desired activity of the original substance. Once the first-generation drugs are discovered and made illegal, later generations are produced, which are a successive line of derivatives of these original drugs. However, their change in chemical structure allows them to bypass the laws that made them illegal (Figure 2).6,7

MDMA has been illegal since the 1970’s, the mere addition of an oxygen group to the MDMA formed Methylone; but this was not banned until 2010.8 Psychoactive substances require its own act, as the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 only covers “controlled” drugs. As there are serval generations of psychoactive substances, they cannot be controlled under the misuse of drug act, due to their rapid re-generation allowing them to evade the current laws. If the psychoactive substance act was not created, it would result in the amendment of the Misuse of Drugs act 1971 every time a new generation is discovered. (Graph 2).9

Graph 2 displays the overall increase in deaths caused by NPS’s, which highlights the necessity for this act. Since the act was enforced, a decrease in the number of deaths for 2016 was expected; however, it has increased by approximately 7% from 2015. Dr. Owen Bowden-Jones, royal college of Psychiatrists stated that in 2014, “1 person a week [was] dying in the UK from novel psychoactive substances”.8 NPS’s can be perceived as safe by users, as they were once legal. However, not all of the chemicals used to make NPS’s have been consumed by humans before; and whilst the short-term effects of these chemicals are known, the long terms affect remain unknown.10 ‘NPS’s are highly addictive with no known withdrawal substitute or overdose antidote at this time’.10 Not only does it have an effect on health in relation to drug use, but it can also have a damaging effect on weight loss, with one male user claiming he dropped to a weight of just 7 stone due to constantly sleeping and not eating.11 Another user states “he doesn’t even smoke the substance any more to get high, but to stop the stomach pains from the withdrawal”.5 Although they are designed to mimic the effects of known drugs, it appears that the psychoactive versions of the drugs seem to be stronger, therefore psychoactive substances can be perceived as far more dangerous. An example of this is with ‘spice’, which is ‘up to 800 times more potent than cannabis’12 resulting in people who smoke ‘spice’ being 30x more likely to go to A and E than cannabis users.4

In 2013/2014 the Home Office purchased and tested some psychoactive substances of which 19% were found to contain illegal substances controlled under the Misuse of Drugs act 1971;13 thus, emphasising a dangerous reality that it is not always known what an NPS is comprised of. Additionally, the packaging of the NPS’s is meant to contain an ingredient list, however, a lot are sold with missing ingredients or without listing any ingredients.14 An example of this was seen by drug testing expert from Cambridge, who tested three psychoactive substances, all of which contained class B drugs. However, due to the absence of the illegal drugs on the ingredients, they are deemed ‘UK legal’.5 In recent years a play on the word ‘legal high’ has been adopted with their new nickname being ‘lethal highs’. This name would appear to be more appropriate due to the highly damaging effects of legal highs. The BBC spoke to users Kev and Snowy who had abused psychoactive substances for years, they stated it has destroyed a lot of people mentally, including themselves, adding that it makes people more violent. One recounted an experience where ‘[they were] stabbed 3 weeks ago with a screw driver because [they] wouldn’t give somebody some spice’. They also claimed that users knew that they would still be able to get the drugs even though the new law was being enforced later that week.5 The new law does not appear to have placed much fear about accessing the drug for the current users.

Law

The law makes it an offence to:

The purpose of this new law is to define a drug by its effects as opposed to its composition. This is due to the chemical structure constantly changing to avoid legislative control, whilst it still causes the same or similar detrimental effects as the original structure. As a result, when a new drug or a new generation of a known drug hits the market, the police should be able to enforce the new law, preventing further production sale and use. The penalties that can be enforced for these offences can be found in Table 1.15

|

Offences |

Section 4 (production), 5 (supply and offering to supply), 7 (possession with intent), 8 (importation/ exportation) |

Section 9 (possession of a psychoactive substance in a custodial institution) |

|

Maximum penalty on summary conviction in England and Wales. |

Six months' imprisonment, an unlimited fine, or both. |

Six months' imprisonment, an unlimited fine, or both. |

|

Maximum penalty on summary conviction in Scotland |

12months' imprisonment, a fine not exceeding the statutory maximum, or both. |

12months' imprisonment, a fine not exceeding the statutory maximum, or both. |

|

Maximum penalty on summary conviction in Northern Ireland |

Six months' imprisonment, a fine not exceeding the statutory maximum, or both. |

Six months' imprisonment, a fine not exceeding the statutory maximum, or both |

|

Maximum penalty on conviction on indictment |

Seven years' imprisonment, an unlimited fine, or both |

Two years' imprisonment, an unlimited fine, or both |

Table 1 Penalties.

The new law states that to define a substance as psychoactive you must prove that it is capable of producing a psychoactive effect. However, the act does not determine a method used to prove this effect occurs, and without evidence that is able to prove a substance is psychoactive, cases will be disregarded. The crown prosecution service addressed the matter in question stating that in order to a prove a substance is psychoactive a forensic service provider would have to provide evidence that contains the following:

These places a large amount of pressure on the UK’s forensic services to ensure testing is carried out properly, thus minimising delays in proceedings although in-vitro testing can be done for some substances, it is not suitable for all substances, in such circumstances, expert witness may rely on existing literature or research.16 Alternatively, human clinical trials may be carried out if necessary, however, this is a very dangerous and lengthy process and would result in a very big back log of cases waiting on the results.4 At one point, there was a discussion into the possible amendment of the NPS act. This occurred after a judge and the governments’ expert witness stated that ‘laughing gas’ was an exempt substance due to the legislation allowing it to be categorised as a medical product.17 This problem has resulted in the collapsing of 2 trials, which has intern prompted for a full review of the legislation by the crown prosecution service. However, when questioned on whether the legislation was going to be reviewed in the House Of Lords on 6th of September 2017, the Minister of State, Home department replied “the outcomes from the two recent cases involving nitrous oxide are not legally binding, and the Government have no plans to conduct a formal review of the Psychoactive Substances Act 2016 following the two recent cases. We are working closely with the Crown Prosecution Service and the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency on our approach to future prosecutions involving this substance.”18 It would appear that once again, another sizeable problem with this legislation is being ignored.

In December 2016, shortly after the NPS act was implemented, the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 was amended to include synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonists (SCRAs), usually found in ‘spice’. They became classified as Class B drugs and illegal to possess, to ensure that ‘spice’ could not fall victim to the ambiguity of terms that define the NPS act 2016.12

Before the bill was passed in 2016, the advisory council on the Misuse of Drugs wrote a letter to the Home Secretary in July 2015. It stated that the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD) were unable to provide clarification on the term ‘Novel psychoactive substances’ and ‘psychoactive substances’ as they do not have a ‘universally agreed definition’.19 It also stated that ‘psychoactivity cannot be definitively established in many cases in a way that would definitely stand up in a court of law where a high threshold of evidence is required’.19 It also states that psychoactivity cannot be defined through biochemical tests and the only way to do so would be by means of human experience. It is for this reason, that there is a high level of ambiguity in the law. Before publication in 2016, there were no definitive answers regarding so many parts of the law, yet no improvements were made to overcome the highlighted problems. Based on the number of grey areas within the law, acknowledged by ADMD itself, it is astounding that the law was permitted to be published. Poppers managed to evade the law on NPS’s with the ACMD stating that ‘that a psychoactive substance has a direct action on the brain and that substances having peripheral effects, such as those caused by alkyl nitrites, do not directly stimulate or depress the central nervous system.’ Therefore, poppers do not fall under the definition of a psychoactive substance.20

Policing

The law only makes it ‘an offence to produce supply, offer to supply, possess with intent to supply and import or export psychoactive substances’;21 however, there is no offence of personal possession. The act provides the Police with the powers to stop and search, seize and destroy, search vehicles and premises, and enter premises by means of a warrant (Graph 3).22

From (Graph 3) it can be seen that the number of possession of drug offences has decreased over the years, although its use is still prevalent. In 2016/2017, an estimated 147,000 people aged 16-59years used new psychoactive substances.9 This, in combination with other additional drug offences, would appear to increase strain on police resources with the addition of 147,000 NPS offences on top of the existing 83462 other drug offences. By the end of 2016, 620 psychoactive substances were being monitored by the European monitoring centre for drugs and drug addiction.9 When compared to the Misuse of drugs act 1971, there is an excess of 125 substances to monitor under the NPS act, inclusive of the existing 495 drugs under this act.23 Graph 4 shows a drastic decrease by almost half after enforcing the law, followed by a general decrease which would indicate that the law has been successful in reducing the number of incidents. (Graph 4).9

The police have also been successful in stopping 332 shops from selling NPS’s and have closed down 31 ‘headshops’.24 On the contrary, there has been a 25% increase from 163 deaths registered in 2015 to 204 deaths registered in 2016, displaying a significant increase in NPS related deaths.24 Since the new law has passed, a street level gram can now range from 0.5g -0.8g in contrast to the previous 1.5g that formerly cost £10, it will now cost users £40 for the same amount.25 One user claims “street dealers catering for beggars, people are selling it in smaller quantities, targeting the homeless community and people who can’t afford to buy it in bigger amounts.”.26 There is still a very large market for psychoactive substances on the web, with substances being able to arrive at your door step in just 10 days (Table 2).27

Between March and June 2016, the UK saw a reduction from 14 websites selling MDMB-CHMICA in March, to just 2 in June shortly after the act was enforced, displaying one of the positive outcomes of the act has been effective.27 Although it is results like this that we should also be expecting to see on the number of deaths related.

|

Country of origin |

Number of websites identified |

|||

|

March |

% |

Junes |

% |

|

|

USA |

20 |

42.6 |

7 |

18.4 |

|

China |

0 |

0 |

7 |

18.4 |

|

Canada |

0 |

0 |

1 |

2.6 |

|

Europe |

27 |

57.4 |

17 |

44.7 |

|

· Czech Republic |

1 |

2.1 |

0 |

0 |

|

· Europe (country not specified) |

8 |

17 |

10 |

26.3 |

|

· Germany |

1 |

2.1 |

2 |

5.3 |

|

· The Netherlands |

1 |

2.1 |

2 |

5.3 |

|

· Poland |

1 |

2.1 |

1 |

2.6 |

|

· UK |

14 |

29.8 |

2 |

5.3 |

|

· Ukraine |

1 |

2.1 |

0 |

0 |

|

Unknown |

0 |

0 |

6 |

15.8 |

|

Total |

47 |

38 |

||

Table 2 Country of origin for websites selling MDMN-CHMICA in March and June 2016.

Convictions

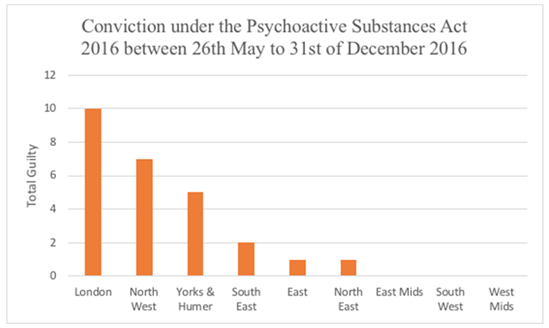

Graph 5 shows the number of convictions under the NPS act 2016 between the 26th May 2016 and 31st December 2017 and Table 2 shows the number of arrests made under the NPS act 2016 between the same dates. With reference to Graph 5, London has secured 10 convictions, in contrast to its 178 arrests seen in Table 3. From (Table 3 & Graph 5) it was calculated that between these dates only 5.6% of the arrests under the NPS 2016 amounted to a conviction in London.

Graph 5 Convictions under the psychoactive substance act 2016 between 26th may to 31st of December 2016.

|

Offence titles |

Number of detainees |

|

Offer to supply a psychoactive substance |

12 |

|

Possess a psychoactive substance in a custodial institution |

2 |

|

Possess a psychoactive substance with intent to supply |

131 |

|

Supply a psychoactive substance |

33 |

|

Total |

178 |

Table 3 Number of offences under the psychoactive substances act 2016 for Metropolitan Police between 26/05/2016 – 30/11/2016.

Furthermore, out of a total 26 UK convictions, a mere total of 4 were imprisoned, which amounts to only a trivial 15%.28 Whilst not all of the suspects were worthy of a prison sentence, it must be acknowledged that many of these convictions which avoid sentencing, can stem from the fact that NPS’s for personal use is not an offence.29 Therefore, all of their offences would be related to some sort of dealing. In October 2016, the conviction for a street dealer was a 12-month community order, 40 hours of unpaid work, and rehabilitation course.4 For a street dealer of cannabis, the recommended sentence is 16 months’ custody by Sentencing Council.30 This is a very big contrast for the conviction of a street dealer of NPS. Even when a conviction is upheld, the sentencing does not seem to be harsh in comparison to drug offences under the misuse of drugs act, even though NPS’s like ‘spice’ are thought to be more harmful than cannabis itself. In 2016 there were 19 arrests and 4 charges and in 2017 there was 16 arrests and 0 charges by West Yorkshire police.31 It would seem that even though the law is being enforced by the police, it is not following through with conviction in court due to a large amount of ambiguity within the law allowing lawyers to by-pass a conviction.

Prisons

NPS’s were commonly used in prison as they were unable to be detected in drug testing as they were not classified as illegal substances. Additionally, substances like spice, largely mimic the effects of cannabis, but without the distinctive smell, making it easier for prisoners to smoke it without being detected.32 Additionally, NPS have a variety of effects and are easy to administer, making them accustomed to most people. They are also very potent but are deceivingly perceived as being ‘safe’.33 Prison seizures of ‘spice’ have increased from 15 in 2010 to around 430 reported in 2014 (Graph 6). A large part of the purpose for the act, is to help take control of the large amount of psychoactive substances within custodial institutions. However, it is unclear how the act will have any effect on the numbers seen in Graph 6, as psychoactive substances were already banned in custodial institutions before the act was passed. So, unless any other measures are put in place, to better detect, or prevent the smuggling of drugs, it is unlikely this act will have any effect on its prevalence within custodial institutions (Graph 6 & Graph 7).33,34

In (Graph 7) it can be seen that in 2014/2015, 83% of the drugs seized being brought into prison were NPS’s which highlights how prevalent their use within prisons in comparison to other drugs really are NPS’s were found to be a cause for concern at 37% of adult male prisons inspected by HM chief inspector of prisons for England and Wales in 2013/2014.35 However, there are further questions as to whether the new law has had an impact on these figures. In a documentary filmed by the BBC, a prisoner stated that people will perform or take part in ‘forfeits’ in exchange for the synthetic drug ‘spice’. Simeon (a former prisoner) served a 2-year sentence, during his time inside he became hooked on ‘spice’ and took part in a dare to smoke half a gram of ‘spice’. Simeon suffered a heart attack and was at one point pronounced dead but managed to make a full recovery. The next day he returned to his cell and smoked another ‘joint’.36 The increased accessibility of NPS in prisons was found to be a source of debt and linking with threats to health and bullying by HM Chief Inspector of Prisons for England and Wales.35 Another documentary was filmed inside HM Prison Bullingdon, where two prisoners recorded a protest video, in which one prisoner stated, ‘the staff are being squeezed to death’.

Another prisoner claims that only two officers would be assigned to one wing which could hold up to 60 people.36 This raises the question of whether this law can be effectively policed when cuts to police funding are resulting in two officers being assigned to a wing of 60 prisoners. Additionally, both of these documentaries were filmed after the act was passed, but their use within the prison remains highly prevalent. As ‘Spice’ can come in a liquid form, this is one of the most common ways of smuggling it into custodial institutions. It is sent into prisons, sprayed onto letters or drawings, via normal post where it is undetected due to the lack of monitoring methods, and the absence of any form of scent. Once the paper is received by the prisoner, they smoke it by breaking off pieces of the paper, rolling it up and putting it in with their tobacco. Each sheet of paper with ‘spice’ on, is worth £50.36 Whilst it is clear that these are unthinkable forms of smuggling drugs into a custodial institution, since the discovery of liquid ‘spice’ paper, there do not seem to be any measures in place in order to detect ‘spice’ via this smuggling method. On September 23rd 2016, the prison & probation ombudsman representative Nigel Newcomen said, “My office has now identified 58 deaths in prison that occurred between June 2013 and January 2016, where the prisoner was known, or strongly suspected, to have been using NPS before their death.”.37

A report published by prison & probation ombudsman later in November 2016 states 79 deaths within prison establishments had been associated with the use of NPS’s between June 2013 and September 2016.9 This means that from January to June an additional 21 deaths related to NPS’s had been recorded, and although the law only came into force in May, such a high number over a 6 month period was unexpected. These figures give the impression that the new law has not had much impact on its use within prisons. When a user, John-Paul, was asked how he was first introduced the use of psychoactive substances, he said prison was where he first discovered the drug. Explaining that he used it as an out for heroin and methadone use5 several users have a distorted perception of the level of impact of psychoactive substances. These individuals stated that they did not think psychoactive substances were as harmful as heroin, due to the fact that psychoactive substances had been legal for so long. One user stated “I’ve tried to get help, but the support services aren’t fit for purpose. They know what to do if you’re on heroin, or crack, but when it comes to legals they’re clueless.”26 This was also reiterated by a Drug worker who argued it is easier to deal with someone who has a heroin addiction, than someone with a ‘spice’ addiction.5 In an attempt to tackle the problem, public health England published a toolkit for prison staff. The aim of the tool kits is to support staff from custodial, healthcare and substance misuse institutions by informing and educating staff about the wide use of psychoactive substances, and the various form that they are available in.33

The Law in other countries

The law was introduced in Ireland in August 2010 and Poland in October 2010, 6years before the UK. Nevertheless, the law has not proved to be fully effective, as Ireland only secured 4 prosecutions between 2010 and 2015.11 One user stated that “when the law changed, and the shops were closed down, people started selling it on every street, it was even easier to get it as there was someone going to get it for you”. In Ireland, the number of consumptions in 15-24year olds increased from 16% to 22% between 2011 and 2014,38 once again highlighting elements of ineffectiveness associated with the law. Poland adopted a slightly different approach to the law, by also making it an offence to be in possession of NPS’s for personal use, with Sentencing of up to 3 years imprisonment. The new law saw a large reduction in the number of reported NPS related poisonings dropping from 258 to 60 in the first month, but it raises the question of whether there were fewer people being poisoned, or if there were fewer people reporting the fact that they had been, due to fear of prosecution under the new law.39 Portugal adopted a conflicting approach to deal with the problem of psychoactive substances.

In 2000 Portugal legalised personal possession of all psychoactive substances under law no 30, which also provided social and health protection for users.40 The government set up the Portuguese Drugs and Drug Addiction Institute (IPDT) which “aimed to contribute for an adequate and effective international strategy, to ensure preventive policies, to reduce primarily drug use among youth people, to guarantee access to treatment and social reintegration, to protect public health promoting safety and enhancing suppression of illicit drug trafficking and money laundering”.40 The UK law has similarities to the Portuguese Law, with there being no criminalisation for personal possession, but the UK law does not focus on helping fix the problem, but merely reducing the availability of substances. Dr. João Goulão, architect of Portugal’s decriminalisation policy states “the biggest effect has been to allow the stigma of drug addiction to fall, to let people speak clearly and to pursue professional help without fear”.41 From (Figure 3),42 it is evident that the approach has been very successful for Portugal.

The Czech Republic initially adopted a very similar approach to the UK with regards to drug laws. In 2010, they tightened drug laws in order to tackle their problem with HIV/AID’s, they recognised that this only made the situation worse. This realisation instigated the adoption of a different approach and in 2011 they followed in Portugal’s footsteps by legalising possession of all psychoactive substances.43 Even though levels of drug use in Portugal appear to be relatively low, reported levels of cannabis use in the Czech Republic are among the highest in Europe.44 Whilst all of these countries show both strengths and weaknesses in their approach to the problem, it can be concluded that each country requires further improvements. However, it must be acknowledged that a perfect solution may never be completely achievable.

Over the years, the use of psychoactive substances has increased, along with the numbers of deaths as a result, highlighting the upmost necessity for the implementation of New Psychoactive Substances Act 2010. However, in the urgency to pass it, it would appear too many mistakes were made. Instead of making adaptations based on the poor success rate of the legislation in Ireland, the UK hastily implemented a similar law. Based on the poor success rate in Ireland, it is difficult to foresee a different success outcome for the UK. Whilst the act has had some success in closing head shops and decreasing the number of UK websites selling MDMB-CHMICA, it has been unsuccessful in more ways than one; with its death toll still increasing and the number of convictions still ceasing to be parallel with the number of offences. In addition to this, sales have been driven underground, and the prices have drastically increased. All of which, have led to the conclusion that level of effectiveness of the psychoactive substances act 2010 is relatively low. Most of these results were predicted by MP Paul Flynn as seen in Figure 4.45

It has been just under 2 years since the act was passed, and already most of what MP Paul Flynn has said, has been verified through research statistics. On the contrary, although MP Paul Flynn has demonstrated a good understanding of the problem at hand to be able to make accurate predictions, he has not provided an alternative method to overcome this issue. Countries other than the UK have also attempted to resolve the problem on psychoactive substance, but it would seem that they too have not found the perfect solution yet. The idea of a ‘blanket ban’ may seem like a logical way to deal with the problem, as the UK, Poland, and Ireland have done. However, from the statistics, it would seem that ‘blanket ban’ may just mask the problem rather than dealing with it completely. If there is a lack of demand, there will be less interest for dealers to supply it.46,47

Therefore, the focus, like Portugal and the Czech Republic, should be on helping provide care and help for users, as If more time was spent helping people with these addictions, fewer people would be buying psychoactive substances, making the interest in selling the substances for dealers decrease. In the future, there could be a chance for the countries to combine their approaches, by focusing on reducing the availability of the substances, as well as providing the necessary help to affected individuals. Drugs are likely to remain an issue within society regardless of what laws are enforced.48,49 Therefore, it is key for the UK to do its best to protect and help individuals in need. It may be a case of combining factors of all the different approaches, or it may be that there is no definitive solution. One harsh reality is that the presence of psychoactive substances remains high with the uncertainty of when, if ever, they can be completely eradicated from society.

None.

None.

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

©2019 O’Hagan, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.