eISSN: 2469-2794

Review Article Volume 12 Issue 3

1University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky, USA

2Be the Change, LLC, USA

Correspondence: Jennifer Middleton, PhD, MSW, LCSW, Associate Professor & director, Co-Principal Investigator, Louisville Trauma Resilient Communities (TRC), Kent School of Social Work and Family Science, 2301 S 3rd St, University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky 40202, USA

Received: August 20, 2024 | Published: September 4, 2024

Citation: Middleton J, Vides B. Mitigating the impact of secondary traumatic stress and compassion fatigue among forensic interviewing professionals: utilization of the four quadrants of self-preservation to promote post-traumatic growth. Forensic Res Criminol Int J. 2024;12(3):223-226. DOI: 10.15406/frcij.2024.12.00423

Forensic interviewing professionals, who regularly engage with children and youth reporting traumatic experiences, are particularly susceptible to secondary traumatic stress (STS) and compassion fatigue (CF). This conceptual article delves into the occupational hazards associated with forensic interviewing, emphasizing the inevitability of STS and CF due to frequent exposure to harrowing accounts of abuse. The article underscores the importance of recognizing these phenomena and differentiating them from burnout—a critical distinction that guides appropriate interventions. Utilizing the "Four Quadrants of Self-Preservation," a trauma- informed framework, the article offers practical strategies for forensic interviewers to mitigate the impacts of STS and CF. This approach promotes resilience through intentional self-care practices across four stages of secondary trauma exposure: before, during, immediately after, and ongoing post-exposure to traumatic material. The article advocates for organizational support in implementing these strategies, emphasizing the ethical imperative to safeguard the well-being of forensic interviewers. The findings suggest that addressing STS and CF not only enhances the personal resilience of professionals but also improves client outcomes, by reducing the likelihood of turnover and professional errors. This article contributes to the growing body of literature calling for trauma-informed practices in forensic settings, highlighting the need for continued research and organizational commitment to support these professionals.

Keywords: forensic interviewer, traumatic stress, self-preservation, human trafficking

Forensic interviewers working with children who have experienced trauma face profound professional challenges. The nature of their work, which involves engaging with sensitive topics such as sexual and physical abuse, human trafficking, and exposure to violence, renders them vulnerable to secondary traumatic stress and compassion fatigue. These occupational hazards are inherent in roles requiring frequent exposure to traumatic material, particularly as forensic interviewers must maintain neutrality while collecting legally defensible evidence. This conceptual article examines the implications of secondary traumatic stress and compassion fatigue in forensic interviewing and explores strategies that promote resilience and post- traumatic growth, contributing to better outcomes for both professionals and their clients. While there has been an increase in the number of empirically supported publications pertaining to the process and procedures of forensic interviewing, few studies address the training, support, and consequences related to forensic interviewers.1

Occupational stress in helping professionals is well-documented across various fields, with terms like compassion fatigue, secondary traumatic stress, burnout, and vicarious traumatization frequently discussed. Figley2 describes compassion fatigue as encompassing both burnout and secondary trauma, which together reduce a caregiver's capacity to empathize with clients. Burnout, as identified by Maslach3 involves chronic workplace stress leading to exhaustion, cynicism, and a diminished sense of efficacy. Secondary traumatic stress, closely resembling PTSD symptoms, arises from indirect exposure to trauma through professional work with affected populations.4 Vicarious trauma involves profound and sometimes permanent changes to professionals’ cognitive schemas and core beliefs about themselves, others, and the world, that occur as a result of exposure to graphic and/or traumatic material relating to their clients’ experiences.5,6 Conceptually, burnout plus secondary trauma equals compassion fatigue. While burnout typically stems from institutional stressors, secondary trauma directly results from the traumatic content they encounter; and when unmitigated, secondary trauma can lead to vicarious trauma.7,8 This dynamic is depicted in Figure 1. Differentiating between these phenomena is crucial for implementing targeted interventions that effectively mitigate the impact of compassion fatigue on the forensic interviewing professional.

Recent literature has continued to explore the prevalence and impact of secondary traumatic stress and compassion fatigue among professionals who work with traumatized populations. Research by Bride et al.9 highlights the occupational health risks associated with these phenomena, noting that secondary traumatic stress and compassion fatigue are prevalent across various sectors, including social work, healthcare, and law enforcement. Specifically, the prevalence of secondary traumatic stress in forensic interviewing professionals, while underexplored, is likely to mirror that in similar high-stress occupations, given the comparable levels of trauma exposure.1 Understanding this prevalence is also critical to developing informed strategies for intervention.

Countertransference is a significant risk factor for forensic interviewers working with children who have experienced trauma. This phenomenon, which occurs when a professional's personal history with trauma or adversity influences their reactions to clients, is especially relevant in forensic settings. Countertransference can exacerbate the effects of secondary traumatic stress and compassion fatigue, leading to impaired judgment and reduced effectiveness in interviews.10 Furthermore, forensic interviewers with unresolved personal trauma or those with prolonged exposure to traumatic narratives are at heightened risk of experiencing compassion fatigue.11 Awareness and proactive management of these risk factors are essential for sustaining professional effectiveness and well-being. In addition, younger professionals and those with less experience are particularly vulnerable to secondary traumatic stress.12 Those with a personal history of trauma are also more likely to experience higher secondary traumatic stress levels. The unpredictability and intensity of forensic work, compounded by system failures and resource limitations, further amplify the risk factors associated with this profession.13 Addressing these risk factors through intentional self-care and organizational support is imperative for mitigating their impact.

Impact on turnover and client outcomes

The effects of secondary trauma and compassion fatigue extend beyond the individual professional, influencing both staff turnover rates and client outcomes. High levels of secondary traumatic stress and compassion fatigue contribute to increased turnover among helping professionals, as these conditions erode job satisfaction and professional efficacy.14 This turnover not only disrupts the continuity of care but also affects the quality of service provided to clients. Professionals experiencing compassion fatigue are at greater risk of making poor decisions, such as misdiagnoses or inadequate treatment planning, which can have serious consequences for client outcomes.15 Given these risks, addressing secondary traumatic stress and compassion fatigue is an ethical imperative. Agencies must prioritize the well-being of their staff to ensure that they are capable of providing high-quality care. This includes offering support systems that encourage early identification and intervention, as well as promoting a culture of self-care among forensic interviewing professionals.

Trauma recovery and resilience

Trauma recovery, or post-traumatic growth, involves processing traumatic experiences in a way that fosters healing and resilience. For forensic interviewers, understanding both the psychological and physiological responses to trauma is essential. The role of the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) is particularly important in this context, as it governs the body’s involuntary responses to stress and trauma. The Polyvagal Theory16 highlights how the ANS operates through various states, including the ventral vagal state, which is optimal for health and well-being, and the sympathetic and dorsal vagal states, which are activated in response to perceived threats. For professionals exposed to trauma, developing an awareness of these autonomic responses is key to managing stress and preventing the escalation of secondary traumatic stress and compassion fatigue. By understanding how the ANS influences their reactions, forensic interviewers can employ strategies to regulate their nervous system, promoting resilience and reducing the impact of trauma on their professional and personal lives.

The four quadrants of self-preservation

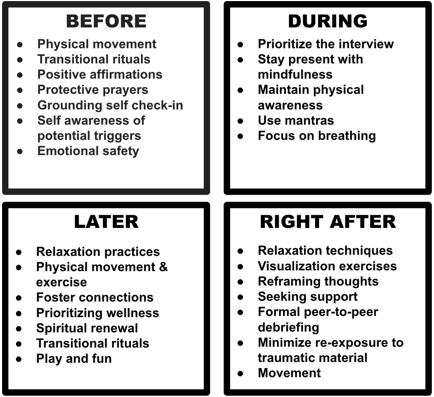

The Four Quadrants of Self-Preservation framework provides a practical approach to building resilience among forensic interviewers. This trauma-informed tool, originally developed and tested with helping professionals who work with trauma-impacted war veterans,17 has practical applications for the mitigation of secondary trauma and compassion fatigue among forensic interviewers as well. The tool emphasizes the importance of engaging in self- care activities across four distinct phases: before, during, and immediately after exposure to trauma, as well as later or ongoing strategies.17 By incorporating strategies tailored to each phase, forensic interviewing professionals can better manage the stress and trauma associated with their work, ultimately fostering resilience and enhancing their capacity to continue serving traumatized populations effectively. Figure 2 depicts the four quadrants of self‐ preservation, which includes Before, During, Right After, and Later/Ongoing strategies. At baseline, when administered to forensic interviewing professionals, the most commonly practiced quadrant is the Later/Ongoing quadrant. Initially, the other three quadrants are often neglected (e.g., rarely practiced without intentional intervention), which can lead to an “unbalanced” self-care plan.

(Adapted from the original Four Quadrants of Self Care published in by Middleton, 2015)

Figure 2 The four quadrants of self‐preservation.

The “before” quadrant

Seasoned forensic interviewing professionals may already engage in certain "before" self- preservation activities as they prepare for interactions with children and families that may be emotionally charged or involve exposure to clients’ traumatic narratives. However, these professionals might not always be consciously aware of their use of these strategies, even though such awareness is critical for effective trauma integration. Furthermore, research strongly suggests that physical self-care—such as adequate sleep, healthy eating, and hydration—is essential before undertaking challenging workdays or client interactions.17 Despite this knowledge, practitioners often neglect these activities, leading to feelings of fatigue, exhaustion, or headaches during the day. Thus, it is crucial to emphasize the importance of physical self-care as a fundamental practice for maintaining professional resilience. Furthermore, transition rituals, such as the transition to and from work and to and from trauma exposure, are another critical component of self-preservation. These transitions can include simple activities like putting on a name badge, reviewing the day's schedule while commuting, or donning a "uniform." Visualization practices can also aid these transitions. For example, a forensic interviewer could utilize a visualization technique involving mentally “shelving” each of their cases at the end of the day, allowing them to leave work-related stress behind.17 Such practices help professionals mentally prepare for the demands of their work.

Conducting a self-check-in before transitioning to work or a traumatic exposure event is also beneficial. This can be modeled after the "Community Meeting," a transition ritual from the Sanctuary Model® that promotes feelings identification, future orientation, and community connection.18 Professionals can adapt this ritual by asking themselves: 1) How am I feeling today? 2) What is my goal for today or this interview? and 3) Who can I ask for help if needed? Regular use of this ritual enhances self-awareness, focus, and a sense of support, all of which are crucial for handling the emotional demands of forensic interviewing.17,19

The “during” quadrant

Self-preservation strategies employed during interviewers’ exposure to trauma are perhaps the most vital for successful trauma integration. Professionals often describe this state as being "on." In these moments, it is essential to focus on the interview, stay present with mindfulness practices, and maintain awareness of physical responses such as breathing and posture. Techniques such as intentionally taking a deep breath, relaxing limbs, and opening hands can signal safety to the brain, helping to interrupt the body's stress response.16 The use of mantras, such as "I can help and understand those I serve without having to live their pain," can also facilitate top-down (e.g., prefrontal cortex) control over trauma responses. Additionally, simply acknowledging one's reactions and planning for later intervention can help compartmentalize the trauma, allowing professionals to leave it behind when the interaction ends.17

The “right after” quadrant

Immediately following exposure to traumatic material, it is important for interviewers to engage in intentional self-care to process the forensic interview experience. Effective strategies include body awareness exercises, relaxation techniques, movement (e.g., a walk), breathing exercises, visualization (e.g., letting go of distressing images), and reframing thoughts. Even basic actions like drinking water can help mitigate the physiological impact of the body's stress response.17 Support from colleagues is also crucial during the post-exposure phase. This can take the form of supervision, collaborative supervision, informal debriefing, learning circles, and case reviews. The key to successful recovery from secondary traumatic stress is qualitative listening—setting aside all distractions and offering undivided attention to the colleague in need. As such, formal peer-to-peer debriefing sessions are a common practice following particularly traumatic interactions. To ensure these sessions are constructive, they should be transformed from informal venting sessions into structured, intentional debriefings. Key rules include seeking permission to debrief, avoiding overwhelming the listener, focusing on personal reactions rather than the traumatic material itself, and using a self-reflection framework to guide the discussion. This approach can help integrate traumatic memories and prevent the burnout of support systems.17

The “Later/Ongoing” Quadrant

Longer-term self-care strategies that can be implemented outside of work are also essential. These include relaxation practices, physical movement and exercise, prioritizing wellness, fostering social connections, engaging in spiritual renewal, and even planning for intentional playful, fun activities outside work to engage creativity and resilience. Additionally, forensic interviewing professionals should focus on the positive impacts of their work by creating transformational meaning and identifying vicarious resilience.17,21–23

The inevitability of secondary trauma and compassion fatigue in forensic interviewing necessitates a proactive approach to managing these occupational hazards. Agencies must take the lead in providing education, support, and resources to help professionals navigate the challenges of their work.1,20 At the same time, forensic interviewers must be vigilant in implementing self- care strategies that promote resilience and post-traumatic growth. By doing so, the field can ensure that those who work with traumatized children are equipped to provide the best possible care while safeguarding their own well-being. Future research should focus on empirically validating the effectiveness of interventions like the Four Quadrants of Self-Preservation in reducing secondary traumatic stress and compassion fatigue among forensic interviewers. Additionally, exploring the long-term impact of these strategies on professional retention and client outcomes would provide valuable insights for practitioners and policymakers alike.

None.

The author declares there is no conflict of interest.

©2024 Middleton, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.