eISSN: 2575-906X

Research Article Volume 2 Issue 6

1Department of Economic Studies, The MwalimuNyerere Memorial Academy (MNMA)-Zanzibar, Tanzania

2Faculty of Science, Technology and Environmental Studies, Open University of Tanzania, Tanzania

Correspondence: Adili Y Zella, Department of Economic Studies, The MwalimuNyerere Memorial Academy (MNMA)-Zanzibar, PO Box 9193, Dar ess Salaam, Tanzania, Tel +255 222820041, +255 787 260448

Received: October 15, 2018 | Published: November 12, 2018

Citation: Zella AV, Saria J, Lawi Y. Consequences of climate change and variability in managing selous-niassa transfrontier conservation area. Biodiversity Int J. 2018;2(6):500-516. DOI: 10.15406/bij.2018.02.00105

Climate is changing and that the changes are largely due to increased levels of carbon emissions into the atmosphere caused by changes of land uses as a result of anthropogenic activities. Considering the impacts of climate change insisted the need for new conservation areas to fill connectivity gap between protected areas (PAs) or transfrontier conservation areas (TFCAs) through habitat corridors so as to enable species migration with their climatic niche. The study aimed at examining the consequences of climate change and variability in managing TFCAs using Selous-Niassa TFCA as a case study. Specifically, the study intended to; examine access to land and land tenure, socio-economic activities resulted from climate change and variability, and property damage and human life caused by wild animals in the study area. Data were collected using questionnaire survey, key informants interviews, focus group discussions, direct observation and secondary materials. Collected data were contently and statistically analysed. Results shows that 86.7% of respondents claimed that land allocated for settlement, agriculture and livestock keeping is not enough as result of human-wildlife conflict. However, shifting cultivation; encroachment for fuelwood, logging, and mining; settlements in migratory routes; and wildfires are some of socio-economic activities resulted from climate change and variability. The encroaching activities are accelerated by socio-economic factors which are positively statistically significant includes sex (b=0.153, p<0.05), years spent in a village (b=0.161, p<0.05), and size of land owned (b=0.484, p<0.05). Furthermore, compensations from property damage and human life caused by wild animals are realistically immensurable. The study concludes that, the management of the study area is unsustainable and the need for inclusion of the area into connected PAs ecosystem of the Selous-Niassa TFCA or formulation of sustainable participatory management strategies of the area.

Keywords: climate change and variability, transfrontier conservation areas (TFCAS), wildlife/biodiversity corridors

Background to the study

Transfrontier Conservation Areas (TFCA) can be defined as fairly large areas, on both sides of frontiers between two or more countries and cover large-scale natural systems encompassing one or more protected areas.1‒4 TFCAs involve a unique level of international co-operation between the participating countries, particularly issues related to the opening of international boundaries and within each region. The history of transfrontier conservation areas (TFCAs) can be traced back to 1932 with the first one established between Canada and the USA.3,5 Since then a steady trickle of these collaborative conservation initiatives has emerged in almost all continents, but Africa TFCAs starts in 1990s.6 Africa has its own perspectives on TFCAs, seeing them in most cases not just as good vehicles for biodiversity conservation, but also as drivers for socio-economic upliftment.7‒9 Few continents can rival Africa in wildlife-based tourism, but these tourism opportunities often remain underutilized. Africa has recognized TFCAs as worthy ventures with multiple potential benefits, but it will take political will to make this potential become reality.10,11 Many TFCAs in Africa are connected by wildlife corridors which extended in various ranges depending on conserved species.12‒15

Wildlife corridors have been widely advocated in conservation planning as a way to help reduce effects of habitat disintegration.10,12,16‒26 Habitat fragmentation can be natural (such as the distribution of alpine habitat) or human-induced, and may occur on many scales.27‒29 The major effects of habitat fragmentation may be additional to those that occur from habitat loss, including increased external influences (such as invasion or predation), altered microclimate (e.g. associated with evapo-transpiration, wind and hydrological cycles) and increased isolation from other areas of similar habitat.4,25,30,31 Longrun destruction, reduction or fragmentation of the sizes of corridors around the protected areas threatens the persistence and viability of many protected species due to reduction in mobility.12,15,32 Besides, damages or fragmentation and blockage of migratory corridors expose the large bodied migratory species such as elephants, which require large home range to extinction. Thus, appropriate management of wildlife corridors provides various ecological benefits to the wildlife. The benefits include returning the landscape to its natural connected state, allow species to migrate between core areas of biological significance, increase gene flow and reduce rates of inbreeding. All these benefits improve species fitness and survival.7,15,33,34 Corridors in particular despite allowing greater mobility,7,11,35 are potential for species to escape predation and respond to stochastic events such as fire. Additionally, corridors allow species to respond more easily to long term climatic changes.7,36,37

It is widely recognized that the decisions for allocation of land to protected areas (PAs) are based on three categories of reasons: pragmatic, ecological and socioeconomic. The Practical reasons for the establishment of PAs are based on factors such as low productivity and availability. The ecological reasons are based on naturalness, uniqueness, ecosystem diversity, integrity, and size while the socioeconomic reasons are based on social and economical principles.4,12,38 The establishment of many PAs including wildlife corridors in Eastern and Southern Africa followed practical and economical criteria.4,12,37,39 Responding to the ecological and socioeconomic benefits of connected ecosystems, a wide range of TFCAs projects have been proposed or are currently being implemented. Selous-Niassa TFCA is among SADC TFCAs projects.

SADC TFCAs established based on instruments such as the Declaration and Treaty of the Southern African Development Community (1992); the SADC Regional Indicative Strategic Development Plan – RISDP (2004); the SADC Wildlife Policy and Development Strategy (1997); the SADC Forestry Strategy (2010); the Biodiversity Strategy (2007) and the SADC Policy and Strategy for Environment and Sustainable Development (1996). Additionally, there are agreements through which the Member States commit themselves to collaborate in attaining regional integration and sustainable social and economic development such as the Protocol on the Development of Tourism (1998); the revised Protocol on Shared Water Courses (2000); and the Protocol on Forestry (2002). In the Protocol on Wildlife Conservation and Law Enforcement (1999) the Member States have made a commitment “to promote the conservation of shared wildlife resources through the establishment of Transfrontier Conservation Areas (TFCAs)”.

At the international level TFCAs complement the goals and objectives of a number of conservation conventions to which many SADC Member States are signatory or party such as the African Convention on Nature and Natural Resources (1968); UNESCO’s Man and Biosphere Programme (1971); the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands Conservation (1971); World Heritage Convention (1972); Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Flora and Fauna (1973); Convention on Migratory Species (1979); Convention on Biological Diversity (1992); the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (1992); and the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (1994). These Conventions urge the signatories and the parties to collaborate in the sustainable utilization of shared natural resources and encourage them to actively involve local communities in the management of the natural environment and in the equitable sharing of benefits derived from the resources therein.

Improving landscape connectivity of Selous – Niassa TFCA claimed to be high on Tanzania and Mozambique political agenda, evidenced by signed of the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on May, 2015 for protection of the TFCA with governments’ instigation. However, establishment of co-management of the TFCA, General Management Plan (GMP) and a strategy to restore and manage ecological connectivity of the TFCA is still silence. The situation accelerates deterioration of the TFCA ecosystem. Furthermore, Selous –Niassa TFCA is connected with corridor on which corridor dwellers resides and practices various socio-economic activities which hamper biodiversity and ecosystem services and contribute to climate change and variability on one way and restrict wildlife adaptation to climate change on the other way.

Statement of research problem

Transfrontier conservation areas (TFCAs) are still a relatively new phenomenon in Africa.3,6,37 The fragmentation of habitat into small patches is a major threat for terrestrial biodiversity in TFCAs.5,39‒41 Fragmentation can inhibit dispersal, reduces gene flow, decrease food availability, and increase the amount of edge habitat where predation and edge effects are more likely. As the climate varies and changes, many species move to new habitats in the landscape and fragmentation impedes range shifts in those that have trouble crossing gaps between patches within an ecosystem.42

Selous – Niassa TFCA is one among SADC TFCAs which link the two protected areas (PAs) by a corridor (URT, 2005). Aim of the corridor is to connect fragmented patches of habitat within TFCA ecosystem to support species dispersal, persistence, and adapt to climate change.11,14,29,37,43 Selous – Niassa wildlife corridor consists of three land tenure structure; state (Game Reserves, Forest Reserves and Wetlands), communal (Wildlife Management areas and Village Forests) and individual ownership (land owned legally or public land (always forested areas) used for various socio-economic activities).4,44,45 These socio-economic activities degrade corridor habitats and contribute to climate change and variability. Some of these activities include uncontrolled wildfires; agricultural expansion due to high human population growth; mining and logging; and increased human – wildlife conflicts due to blockage of corridor resulted from ribbon strip developments along the major roads within the corridor.4,37,46 There is scanty information concerned consequences of climate change and variability in managing Selous –Niassa TFCA. However, encroachments of the TFCA disturb the wildlife movements and lead to a dramatic reduction of wildlife populations and local extinction of some species. Baldus & Hann46 and Baldus et al.47,48 reported poaching to be extensive in Selous-Niassa TFCA.

Therefore, this study was intended to examine consequences of climate change and variability in managing TFCAs by using Selous – Niassa TFCA as a case study.

Research objectives

General objective

The main objective of this study was to analyse consequences of climate change and variability in managing Selous – Niassa transfrontier conservation areas (TFCAs)

Specific objectives

Specifically the study intended to examine:

Research methodology

Description of the study area

The study was carried out in eastern Selous-Niassa TFCA with an area of 1, 462, 560hectares extends across southern Tanzania into northern Mozambique between 10ºS to 11º40’S with north-south length of 160 to 180km (Figure 1). SNWC comprises of two parts, western part (administratively passes in Namtumbo and Tunduru Districts of Ruvuma regions in southern Tanzania) and eastern part (administratively passes in Liwale, Nachingwea, Masasi, and Nanyumbu Districts). This study concentrated in eastern part. In eastern SNWC, migration of elephants, buffalos and zebras has been observed.49,50

Two migratory routes have been identified as follows:

These routes forms SNWC called Selous-Masasi corridor includes the Msanjesi (2,125ha) and the Lukwika-Lumesule (44,420ha) GRs in Masasi and Nanyumbu Districts respectively and areas of Liwale, Nachingwea, Masasi and Tunduru Districts.

The study area comprise wildlife management areas (WMAs) bordering Selous, Msanjesi and Lukwika-Lumesule game reserves (MAGINGO WMA, NDONDA and MCHIMALU proposed WMAs respectively) which are within Liwale, Nachingwea/Masasi and Nanyumbu Districts respectively. In this study three villages namely Mpigamiti, Kilimarondo and Mpombe within MAGINGO WMA and NDONDA and MCHIMALU proposed WMA were purposely selected for ground of the study.

Research design

A cross sectional research design was employed.

Sampling procedure and sample size determination

Sampling procedure

Mpigamiti, Kilimarondo and Mpombe villages in Liwale, Nachingwea and Nanyumbu districts were purposively selected as those found within eastern wildlife corridor of Selous-Niassa TFCA. The study villages selected based on the conditionas that (i) both are within the corridor, (ii) both are members of wildlife management areas (WMAs) (Mpigamiti – MAGINGO WMA, Kilimarondo – NDONDA proposed WMA and Mpombe-MCHIMALU proposed WMA) and (iii) Mpigamiti is within the start of the corridor, Kilimarondo at the middle of the corridor while Mpombe is within the destination of the corridor in Tanzania.

A list of all households from the updated village register book in the study villages was the sampling frame. Sampling unit for this study was a household. Household was defined as a group of people living together and identifying the authority of one person the household head, who is the decision maker for the household.51 Simple random sampling, was used to identify the sample units. In this method every household has an equal chance of being selected. Where a candidate happened to come from the same household, one was dropped.52‒55

Sample size determination

The sample size for each study village comprises of 30households whereby 10households were drawn from each income group (low, medium and high) as described in village’s fact sheet. Sample size in socio-economic studies was decided by the researcher depending on the nature of study but should be at least 30 units as supported by many scholars.55‒59 Judgmental/purposive sampling technique was used to obtain 17 key informants. The distributions of sample size are shown in Table 1.

Category of respondent |

District |

Villages |

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Mpigamiti |

Kilimarondo |

Mpombe |

Total |

||

Households |

|

30 |

30 |

30 |

90 |

Village Executive officers (VEOs) |

|

1 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

Village Natural Resources Officers (VNROs) |

|

1 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

Project Manager of LLM (PLLM) |

1 |

|

|

|

1 |

District Game officers (DGOs) |

3 |

|

|

|

3 |

Sector warden of SGR (SWS) |

1 |

|

|

|

1 |

Village Development Officers (VDOs) |

|

1 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

WMA Chairpersons (WCs) |

3 |

|

|

|

3 |

Total |

8 |

33 |

33 |

33 |

107 |

Table 1 Respondent sample composition

Pilot study

Prior to actual data collection, pilot study was conducted so as to provide a general scenario of the study area and testing the questionnaire in order to verify if the questions could be understood by the respondents. Questionnaire pilot-testing was done in Majonanga village which is within Selous-Niassa TFCA in Ndonda proposed WMA in Nachingwea District and is adjacent to Msanjesi GR aimed to test questionnaire wording, sequencing and layout; and to estimate response rates and time.

Data collection methods

In order to attain the overall aim and objectives of this study, a combination of methods and techniques were employed. Different scholars stress the need to use a combination of methods and develop a more “rigorous methodology” as they are useful to corroborate and ensure validity, not providing proof but improving consistency across methods in a process of triangulation.55 This study consisted two phases of data collection whereby primary and secondary data were collected.

Secondary data

Secondary data was collected using literature surveys. Both quantitative and qualitative data were acquired.

Primary data

Primary data for this study were collected using survey (household questionnaire survey and key informants interview); participatory rural appraisal (focus group discussion and direct observation). Both quantitative and qualitative data were acquired.

Data analysis

Quantitative data from questionnaire was analysed statistically. Qualitative data from focus group discussions (FGDs) and key informants were analysed through content analysis. Content analysis is useful in analyzing details of the components of verbal discussions held with key informants and FGDs.

Statistical analysis

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 20 and Microsoft Excel Version 2007 were employed. The obtained data were statistically analysed using descriptive and inferential tests.

Descriptive statistical analysis

Analysis of quantitative data by descriptive statistics was involved frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations of variables such as age, marital status, sex, education level, household size and income. Also examining relationship between two variables by the use of cross tabulation method was employed.

Inferential Statistical Analysis

Inferential statistical analysis was involved application of multiple regression model used to determine socio-economic factors influencing encroachment of wildlife corridor. Multivariate regression analysis was run to assess the influence of independent variables on dependent variable. The model was expressed as follows:

Where:

Yi=encroachment of TFCA (presence of socio-economic activities that have adverse effect on ecosystem)

ß’s=coefficients to be estimated

B0=constant coefficient (intercept of the equation)

Xi=independent variables

i=1,2, 3……j

ei=error term

The hypotheses tested were:

Ho: βi =0 that is regression coefficients are equal to zero implying that socio-economic factors (independent variables) have no significant influence on encroaching Selous – Niassa TFCA (p<0.05)

Ha: βi≠0 that is regression coefficients are not equal to zero meaning that socio-economic factors have significant influence on encroaching Selous – Niassa TFCA (p<0.05)

From the above, the variables included in the regression model were:

X1=Age

It was hypothesized that age of respondents influence encroachment of Selous – Niassa TFCA. Young respondents (≤ 35 years), middle-aged (36–45 years) and respondents over 60 years old (commensurate with Tanzania’s mandatory retirement age of60) differed in the level of encroachment in the TFCA. Young people depended more on natural resources extraction for their survival compared to older people who were more likely to have income from wages, salaries or pensions, and less income from natural resources. Therefore, age has negative regression coefficient (-).

X2=Sex

This could have positive coefficient (+) in the sense that sex influence encroachment in Selous – Niassa TFCA as male are more destructive compared to women as almost most poachers arrested in the TFCA are male.

X3=Education level

This could have a negative coefficient (-). It was hypothesized that respondents with higher education has low influence on encroachment of Selous – Niassa TFCA compared to respondents with low education. The reason behind is that, respondents with higher education can be employed in various private and government sectors operating in Districts where Selous – Niassa TFCA lies.

X4=House hold size

The regression coefficient for household size was expected to be positive (+). The reason behind is that large household size have many mouths to feed resulting in increasing food production and other necessities. This scenario accelerates encroachment of Selous – Niassa TFCA as ethnicity of the area encourages polygamy.

X5=Household income

Household income could have positive coefficient (+) as higher income families mostly employed or business oriented respondents compared to low income families who engage in illegal extracting natural resources to supplement necessities. Furthermore low income families are easier to corrode with outsiders of Selous – Niassa TFCA to encroach valuable natural resources

General information of respondents in the study villages of selous-niassa TFCA

The selected three study villages for ground Truthing and acquiring new study information were Mpigamiti, Kilimarondo, and Mpombe villages in Liwale, Nachingwea and Nanyumbu districts respectively. The study population comprised of males and females with different ages, family size and education background (Table 2). Of the household heads interviewed, 83.3% were at least 25years old. This was important to the management of Selous-Niassa TFCA because they understand the historical trend of their areas as well as existing indigenous technical knowledge (ITK).

Information |

Study villages |

Pearson’s chi-square |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mpigamiti |

Mpombe |

Kilimarondo |

Overall |

Exact Significance: |

|

(2-sided) |

(1-sided) |

|||||

Age class: |

||||||

18-24 Years |

6(20.0)1 |

5(16.7) |

4(13.3) |

15(16.7) |

|

|

25-35 Years |

8(26.7) |

11(36.7) |

10(36.7) |

29(32.2) |

0.420 |

0.225 |

36-44 Years |

9(30.0) |

8(26.7) |

8(26.7) |

25(27.8) |

|

|

45-65 Years |

5(16.7) |

3(10.0) |

5(16.7) |

13(14.4) |

|

|

> 65 Years |

2(6.7) |

3(10.0) |

3(10.0) |

8(8.9) |

|

|

Sex: |

||||||

Male |

16(53.3) |

13(43.3) |

15(50.0) |

44(48.9) |

|

|

Female |

14(46.7) |

17(56.7) |

15(50.0) |

46(51.1) |

0.606 |

0.303 |

Education background: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Informal education |

6(20.0) |

11(36.7) |

8(26.7) |

25(27.8) |

|

|

Basic adult education |

6(20.3) |

5(16.7) |

4(13.3) |

15(16.7) |

|

|

Primary |

12(40.0) |

11(36.7) |

12(40.0) |

35(38.9) |

0.491 |

0.068 |

Secondary |

4(13.3) |

3(10.0) |

4(13.3) |

11(12.2) |

|

|

> secondary |

2(6.7) |

0(0.0) |

2(6.7) |

4(4.4) |

|

|

Household size: |

||||||

1-5Persons |

14(46.7) |

18(60.0) |

14(46.7) |

46(51.1) |

|

|

6-10Persons |

13(43.3) |

9(30.0) |

12(40.0) |

34(37.8) |

0.572 |

0.368 |

11-15Persons |

3(10.0) |

2(6.7) |

4(13.3) |

9(10.0) |

|

|

> 15Persons |

0(0.0) |

1(3.3) |

0(0.0) |

1(1.1) |

|

|

Income per month: |

||||||

Below TZS 30 000 |

3(10.0) |

4(13.3) |

5(16.7) |

12(13.3) |

|

|

TZS 30 000-59 000 |

11(36.7) |

9(30.0) |

9(30.0) |

29(32.2) |

|

|

TZS 60 000-89 000 |

6(20.0) |

8(26.7) |

9(30.0) |

23(25.6) |

1.000 |

0.206 |

TZS 90 000-119 000 |

4(13.3) |

3(10.0) |

3(10.0) |

10(11.1) |

|

|

TZS 120 000-149 000 |

2(6.7) |

3(10.0) |

3(10.0) |

8(8.9) |

|

|

TZS 150 000-179 000 |

3(10.0) |

1(3.3) |

1(3.3) |

5(5.6) |

|

|

TZS 180 000-209 000 |

1(3.3) |

1(3.3) |

0(0.0) |

2(2.2) |

|

|

>TZS209000 |

0(0.0) |

1(3.3) |

0(0.0) |

1(1.1) |

|

|

Table 2 Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents

1Figures outside and inside the parentheses are frequencies and percentages respectively.

The study villages were found to have large household sizes. Results show that 53.3% have 1-5 persons per household and 46.7% have more than 5 persons. This is due to the culture of marrying many wives (polygamy) which results into a lot of dependents to feed and take care of. Education background of the surveyed population was at most primary education (85.0%), very few had at least secondary education (3.3%). This is due to shortages of schools especially primary schools resulting into children walking long distances to school. There was no nearby secondary school in Mpigamiti or Mpombe villages. This implies that, low education level provides low payment employment opportunities to tourism industry within Selous-Niassa TFCA.

The study villages found to have low income per month resulted mostly from small-scale farming compared to standard living cost needed in the study area. Results show that 71.1% have income less than TZS 90,000, and 28.9% above TZS 90,000, whereas 45.6% below TZS 60,000 which means below TZS 2,000per day (Table 2). This shows that those employed villagers have high income compared to non-employed (Table 3) which shows that 54.6% of employed villagers have income of above TZS 150,000per month compared to unemployed villagers 82.3% have an income of below TZS 90,000per month. Moreover, the chi-square test indicated statistical insignificance on all socio-demographic characteristics of respondents in study villages.

Income per month: |

Employed |

Unemployed |

Overall |

Below TZS 30 000 |

0(0.0)1 |

13(16.5) |

13(14.5) |

TZS 30 000-59,000 |

0(0.0) |

27(34.2) |

27(30.0) |

TZS 60 000-89 000 |

0(0.0) |

25(31.6) |

25(27.8) |

TZS 90 000-119,000 |

0(0.0) |

9(11.4) |

9(10.0) |

TZS 120 000-149,000 |

5(45.6) |

5(6.3) |

10(11.1) |

TZS 150 000-179,000 |

3(27.2) |

0(0.0) |

3(3.3) |

TZS180 000-209,000 |

2(18.1) |

0(0.0) |

2(2.2) |

>TZS 209 000 |

1(9.1) |

0(0.0) |

1(1.1) |

Table 3 Income level of respondent per month

c2=45.445, P<0.001(Statistically significant at 0.001 level of significance)

1Figures outside and inside the parentheses are frequencies and percentages respectively.

Also the results show that the study population has 12.2% of employed villagers while 87.8% are unemployed. Mostly those villagers who are employed work in Tourism industry and those who are not employed are likely to engage themselves in other socio-economic activities including encroachment of wildlife and forest resources. Those unemployed people are the one who are poor compared to employed villagers.

The study villages observed to have large household size with low income of her people as a result concentrates on utilizing protected wildlife and forest resources. Alternatively, those employments in tourism industry has its consequences, for instance foreigners are paid much compared to locals and this is common in many tourism companies includes Tanganyika Wildlife Safaris (TAWISA), Bushman Hunting Safaris and Tanganyika Wildlife company Ltd (TAWICO) which have invested in Selous-Niassa TFCA. Furthermore, the chi-square test indicated statistical significance (P<0.001, i.e c2=45.445) on monthly income of employed and unemployed households (Table 3). This implies that, affirmative action policies may need to be adopted to improve payments of the excluded and to enhance equitable access to job opportunities.

Access to land and land tenure in the study area

The land tenure system in the study area is given in Table 4. The dominant land ownership system is individual land obtained through inheritance (83.3%). This is followed by rent land (16.7%) where the majorities are females who were either divorced or widowed because the traditional rules for accessing land did not favor them. The minimum farm size owned by an individual farmer was one hectare, while the maximum farm land was 15hectares. Average farm land per farmer was 1.2 ha. Regarding land area, 80% of the respondents have land parcels between 1-3hectares and 20% had more than three hectares. However, 86.7% of the respondents claimed that land was not enough.

Information |

Villages |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mpigamiti |

Kilimarondo |

Mpombe |

Overall |

(a)Land ownership: |

||||

Individual |

27(90.0)1 |

25(83.3) |

23(76.9) |

75(83.3) |

Rent |

3(10.0) |

5(16.7) |

7(23.3) |

15(16.7) |

(b) Size of land owned hectares: |

||||

1 - 3 ha |

24(80.0) |

21(70.0) |

27(90.0) |

72(80.0) |

4 – 6 ha |

4(13.4) |

5(16.7) |

2(6.7) |

11(12.3) |

7 - 10 ha |

1(3.3) |

2(6.7) |

1(3.3) |

4(4.4) |

11-15 ha |

1(3.3) |

1(3.3) |

0(0.0) |

2(2.2) |

> 15 ha |

0(0.0) |

1(3.3) |

0(0.0) |

1(1.1) |

(c) Land available: |

|

|

|

|

Enough |

2(6.7) |

4(13.4) |

6(20.0) |

12(13.3) |

Not enough |

28(93.3) |

26(86.6) |

24(80.0) |

78(86.7) |

(d) Possibility to get more land: |

||||

Yes |

23(76.7) |

25(83.3) |

28(93.3) |

76(84.4) |

No |

6(23.3) |

5(16.7) |

2(6.7%) |

14(15.6) |

(e)Location of owned land: |

||||

Within migratory routes |

2(6.7) |

2(6.7) |

1(3.3) |

5(5.5) |

Five km from core PA |

2(6.7) |

2(6.7) |

1(3.3) |

5(5.5) |

Within the WMA |

0(0.0) |

5(16.7) |

10(33.3) |

15(16.7) |

In the planned area |

23(76.7) |

20(76.7) |

18(60.0) |

61(67.9) |

In wetland area |

3(10.0) |

1(10.0) |

0(0.0) |

4(4.4) |

Table 4 Land ownership in study villages

1Figures outside and inside the parentheses are frequencies and percentages respectively.

For possibilities to get more land for cultivation, 78.3% claimed that it was possible either through formal application to the village government (81.7%), buying from those with big farms (10.0%) and renting on temporary basis (8.3%) (Table 4). Even though, the majority of respondents (85%) indicated the possibility of getting additional piece of land (Table 5). During the focus group discussions it was found that there is a problem of fertile land for rice farming in Mpigamiti village resulted to land use conflicts. The conflict arose in 2010 after MAGINGO WMA getting user right for the area while immigrants invaded the area and cultivated protected land and uses water from the source of Liwale River (Mpigamiti spring) without prior consultation and permission from the village, MAGINGO leaders and District authority as the river is only source of water to Liwale District. This is due to divisions of former village of Mpigamiti into three villages (Mpigamiti, Namakololo and Mitawa) while during formation of the WMA it was one village. Thereof, distribution of income from WMA goes to only one village (Mpigamiti) and other two remaining villages get nothing contrary to sharing their land to WMA.

|

|

|

|

95% CI of the Difference: |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

T |

Df |

Sig. (2-tailed) |

Mean Difference |

Lower |

Upper |

-1.07E+03 |

59 |

0 |

-58.767 |

-58.88 |

-58.66 |

Table 5 T-test for possibility to get more land for cultivation by households in study villages

CI, confidence interval

T-test in Table 5 indicated statistical significance (p=0.05) on possibility to get more land for cultivation by households in study villages through various means includes application to the village government, buying or rent.

Findings from the analysis of variance (ANOVA) in Table 6 shows that there was a significant variation (p<0.05) of means to acquire land for cultivation by households in study villages.

Source of variations |

Sum of Squares |

Df |

Mean Square |

F |

Sig. Level |

Between villages |

1.067 |

1 |

1.067 |

2.994 |

< 0.05 |

Within villages (error) |

20.667 |

88 |

0.356 |

|

|

Total |

21.733 |

89 |

|

|

|

Table 6 One-Way ANOVA for means to acquire land for cultivation by households in study villages

*Statistically significant at 0.05 level of significance

Furthermore, information obtained from MAGINGO and MCHIMALU WMAs offices and DLOs shows that, study villages bordering Selous, Msanjesi and Lukwika-Lumesule GRs have land use plans made by Tanzania Land Use Plan Commission (TLUPC) in collaboration with Ministry of Land, Housing and Settlement (MLHS); and Liwale, Nachingwea and Namyumbu District Councils (LDC and NDC) in 2008, 2010 and 2012 respectively. The planning process was funded by WWF however excluded SGR, MGR and LGR which in one way or another is among of the cause of border conflict between adjacent villages and PAs. It was explored that, study villages land use plans maps don’t have “buffer zones” as suggested by Wildlife Conservation Act No. 12 of 1974 and its successor No.5 of 2009.

Therefore, this shows that, all professionals were only listening to villagers without considering other laws and policies like Wildlife, Environmental, Forest and others. For instance, during 2015 boundary conflict resolution between MAGINGO WMA and SGR done by the committee made by then Minister of MNRT which involved professionals from TLUPC, LDC, MLHS, MNRT and SGR also Village elders of nine villages forming WMA includes Mpigamiti, Ndapata, Barikiwa, Chimbuko, Kikulyungu, Kimambi, Mirui and Naujombo (MWMA and SGR office reports, 2016). At the end of resolution, all villages except Kikulyungu agreed with the Government Notice No. 275 of 1974 which declares the boundaries of SGR. The zoned land area for WMA in Kikulyungu village is no more favourable for wildlife conservation as it was converted to agriculture activities.

Socio-economic activities resulted from climate change and variability in the study area

Agriculture

Agriculture is a major economic activity and source of income in Selous-Niassa TFCA. Many villagers in Liwale, Nachingwea and Nanyumbu Districts practice shifting cultivation associated with destroying Miombo forests which are also habitat for wild animals thereafter causing human-wildlife or wildlife-crops interactions/conflicts as the animals moving in their ecological trails and searching their climatic niche. Specifically, this behavior depends on population of the Districts; for instance 2012 census show Liwale District to have a population of 91 380 people with average of one person per 6.7hectares suitable for agriculture and outside protected areas; Nachingwea District have 178 464 people with average of one person per 2.9hectares; while Nanyumbu District have 150 857 people with average of one person per 2.3hectares. This shows that, Nachingwea and Nanyumbu Districts will extend to protected land for agriculture activities if shifting cultivation is not reversed (Table 7).

Information |

Area (in hectares) |

||

|

Liwale District |

Nachingwea District |

Nanyumbu District |

|---|---|---|---|

(a) Food crops: |

|||

Cassava |

12 809 |

8 247 |

27 558 |

Maize |

14 464 |

6 211 |

16 450 |

Rice |

5 998 |

11 99 |

2 154 |

Sorghum |

11 741 |

48 04 |

10 280 |

Total |

33 492 |

20 461 |

56 442 |

(b) Cash crops: |

|||

Cashew nuts |

13943 |

11 397 |

105 820 |

Sesame |

6 800 |

3 445 |

5400 |

Cowpea |

1 400 |

- |

3500 |

Pigeon |

1 220 |

3 341 |

14 000 |

Gram |

4 340 |

- |

9 811 |

Groundnuts |

870 |

3 206 |

15 120 |

Total |

28 573 |

11 389 |

153 651 |

Table 7 Food and cash crops areas

Source: Liwale, Nachingwea and Nanyumbu District Councils Reports, 2017

Cultivated crops in the study area can be categorized into three main groups namely annual, semi perennial and perennial crops. Major annual cultivated crops include maize (Zea mays); rice (Oryza sativa) and sorghum (Sorghum vulgare). Semi perennial cultivated plant species are cassava (Manihot esculenta), sugar cane (Saccharum officinarum), simsim (Sesamum sp), and banana (Musa esente, Musa cavendishii, and Musa sp). Perennial cultivated plant species are cashewnut (Anacardium ocidentale) and coconut (Cocos nucifera). Other minor cultivated plant species are groundnuts (Arachis hypogea), melon (Cucurbita mero) and Pigeon beans (Cajanus cajan). Fruits plant species cultivated in study area include mango (Mangifera indica), orange (Citrus sp) and pawpaw (Carica papaya). However, perennial and semi perennial crops are grown on small scale level but all crops are grown for subsistence and trade, but cashew nuts remains the principal cash crop and sesame emerged as short term cash crop involve highly forests destructions. Production trend varies in different years depending on input and equipments supplied. The following figures (Figure 2) show some of the existing production for Liwale, Nachingwea and Nanyumbu Districts in years:

During in-depth interview with Districts agriculture officers, it was seems that the productions trend are not actual due to the presence of illegal buyers (Chomachoma) where quantity bought are unknown and increase loss of Districts income. Therefore, out of other factors, production variation in years depends on strength of District security on exit routes of that particular year.

The emerged of highly production of simsim (Sesamum sp) seems to overtake cashewnut and becomes the leading source of Districts revenues and households’ income. For instance, simsim production in Liwale District for the year 2015/16 was 7 925 157kg compared to 7 483 874kg of cashewnut amounted TZS15 850 314 000 and TZS 8 980 648 800 respectively. This shows that, simsim production in terms of revenues accrued almost double cashewnut production. However, most of cashewnut are at least fifty years of age and are owned through inheritance, thus accelerates conservation efforts compared to simsim production which is environmental destructive but short time income rewarding activity. There is no actual figure for the land size used for simsim production as most of producers invade and clear public Miombo forests for establishment of farms. This statement evidenced by a large number of “Makonde” from Newala, Tandahimba and Mahuta claimed during focus group discussions to invade the study area.

Also these food and cash crops attract wild animals which are the source of conflict of interests between conservation and agriculture. The study villages show that 88.6% of respondents suffered from wildlife related problems while only 11.4% had not experienced the problem (Table 8).

Information: |

Villages |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mpigamiti |

Kilimarondo |

Mpombe |

Overall |

(a)Availability of problem animals: |

||||

Yes |

28(93.3.7)1 |

24(80.0) |

26(86.7) |

78(86.7) |

No |

2(6.7) |

6(20.0) |

4(13.3) |

12(13.3) |

(b)Common problem animals: |

||||

Elephant (Loxodonta africana) |

26(86.7) |

4(13.3) |

4(13.3) |

30(50.0) |

Bushpig (Potamochoerus porcus) |

20(66.7) |

11(36.7) |

11(36.7) |

31(51.7) |

Vervet monkeys (Chlorocebus aethiops) |

9(30.0) |

17(56.7) |

15(50.0) |

41(45.6) |

Hippos (Hippopotamus amphibius) |

6(20.0) |

5(16.7) |

3(10.0) |

14(15.6) |

Olive baboon (Papio anubis anubis) |

15(50.0) |

8(26.7) |

12(40.0) |

35(38.8) |

Table 8 Problem animals destroying crops and human life

For (b) Multiple responses answers were obtained

1Figures outside and inside the parentheses are frequencies and percentages respectively.

The study found the animals that damage crops in the field are shown in (Table 8). Elephants seem to damage mostly in Mpigamiti village (86.7%) compared to Kilimarondo and Mpombe were vervet monkey take chances by 56.7% and 50% respectively. This indicates that elephant poaching is at alarming rate in Kilimarondo and Mpombe villages compared to Mpigamiti village within the Selous-Niassa TFCA.

Furthermore, rats were reported by many respondents that they cause great damage on stored cereal crops at home compared to fields’ crops. During field observation and focus group discussions it was found that, damage to crops varied from one village to another and from one plot to another within the study area. The most preferred crops by animals were maize, cassava, sugarcane, melon and cashew nuts.

During focus group discussions, community categorized the wild animals that damage crops into three main groups:

Elephants, bush pigs and baboons are animals that cause greater damage to maize farm plots both in wet and dry season. Baboons start to destroy maize seedling immediately after germination. They jab germinated maize seedlings and continue to damage crops in the growing season until they are harvested. Elephant start to feed on maize seedlings between 3-4weeks after germination and continue to damage the crops until they are harvested. The relative ranking of damage caused by elephant varies in the study area. Elephants were found to enter crops most in both wet and dry season depending on the location of the field from the feeding or migratory routes to or from core protected areas. Bushpigs were reported to use stems of maize and sorghum at early stage.

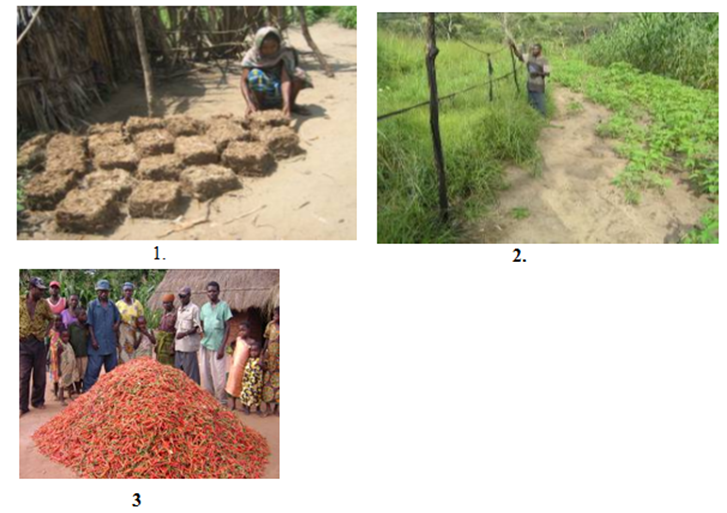

The measures taken by farmers to control include non lethal deterrents applied by farmers include oil chilled ropes and chilled elephant dung blocks. The farmers who applied oil chilled ropes and chilled dungs around their farm plots in the study area had less crops loss or raided by animals especially elephants. These measures experienced in Mpigamiti village were peasants who applied the deterrents of elephants in their farm plots yielded much and had large farms plots compared to those who do not apply (Figure 3). Therefore, as suggested by Kagaruki (2004) crop production in the study villages would be increased if more efforts toward preventing crop damage will be focused on the control of weeds, crop diseases, and smaller species such as bush pigs, baboons, rodents or birds because elephants in many areas within the corridor are deteriorating.

Figure 3 1. Chill-elephant dung bricks. 2. Oil chilled ropes around farm plot. 3. Harvested chilies used in HWC

However, wildlife not only represent problems for people living around them but there is also an overall great deal of respect, affection and positive culture associate with the populations of wild animals. Wild animals are part of people’s lives, their identity and attachment to the land. There might be a considerable faith in the manager’s capability to alleviate problems around communities while protecting natural resources. Nevertheless, major threat hinder sustainable conservation of wildlife is a limited range of opportunities and alternatives in a situation characterized by wide spread poverty and increased population pressure within the wildlife corridors. Therefore, the need to facilitate community mobilization seems to be the pre-requisite for sustainable wildlife management.60

Population growth of people and ghastly land uses in study villages brings pressure on resources available as results of habitat destruction and environmental degradation. During field observation, it was seen that, many farms are within the wildlife corridor and out of planned areas which implies that, people are not only interested with growing crops only but their eyes are on wild animals.

The existence of conflicts within the corridor is based on the differing term-utilization attached to the available resources. The objectives behind the conservation scheme is to conserve natural resources for long-term benefits, while the concern of the inhabitants of the corridor is the need to have a means of livelihood for survival. The different functional interpretations given to the corridor have generated the varying degrees of conflicts experienced.

Encroachment for fuelwood, logging and mining

Encroachment for fuel wood, logging and mining is increasing daily in the study area as alternative source of income for their livelihoods. During direct field observation and focus groups discussions in study area, mining tunnels observed and most of mining practiced within rivers (Liwale, Lumesule, Mbwemkuru, Lukwika and Ruvuma rivers) inside wildlife and forest protected areas found in Selous-Niassa TFCA. Focus groups discussants claimed that, minerals found in the study area are such as white sapphire, green sapphire, blue sapphire, green tourmaline and gold. During in-depth interview with DGOs and passing through District revenues collections records for five years 2011 to 2016, the quantity of mines and revenues accrued by Districts authorities are still a myth.

Illegal logging increased in study area especially in forest reserves, WMAs, and SGR, LLM GRs as these are the only areas in Liwale, Nachingwea and Nanyumbu districts concentrated with valuable trees for logging and timbering. For year 2011 to 2016, LLM arrested 1953 timbers from TFCA in Nachingwea and Nanyumbu Districts while SGR arrested 2217 in Liwale District (LLM and SGR annual reports of 2011 to 2016). Encroachments of forests for valuable trees increased due to emerged application of chainsaws in illegal and legal harvesting contrary to Forest Act of 2002. For instance, the year 2014, twenty six (26) people and more than 4000 timbers which were illegally harvested were arrested inside MAGINGO WMA, Nyera/Kipele forest reserve and open areas by Tanzania forest service (TFS) in collaboration with SGR. The growing number of people, farms and wildlife in the study area are leading to increased conflict between the needs of conservation and development as explained much by World Bank (2008), Nelson (2009 and 2010) and Wilfred (2010).

Tree planting help to reduce shortage of fuelwood and logging which are important for households’ consumption. The study villages found to have high concentration of people who do not adopt trees planting strategy contrary to the national agenda (Liwale DGO, 2017). Most households in study villages depend on natural regeneration of trees to tackle fuelwood shortage and few infrequent practiced private tree planting, agro-forest and communal tree planting (personal observation). This scenario implies more encroachment in Selous – Niassa TFCA.

Settlements in migratory routes

Settlements are amongst the wildlife-human interaction which causes stress on natural resources in Selous-Niassa TFCA ecosystem. In the study villages (Table 9), the respondents don’t see these as great sources of stress on wildlife resources because their effects are seen in a long term basis, instead they rank interaction of wildlife and human/livestock is Very high (56.7%). The villages forgetting that, when make settlement or agriculture in migratory routes automatically interaction with wildlife will be great and the ecosystem will be disturbed as a result affect wildlife range area, genes distribution and migration of wild animals. Whatsoever, agriculture ranked High (65%) and Settlement ranked Medium (63.3%). Furthermore, statistical tests shows that, settlement has a significant mean as a source of stress in Selous-Niassa TFCA compared to other sources as indicated in Table 9. This shows that the wildlife population is at risk. Therefore, unless strategies to alleviate the situation are in place, environmental degradation including loss of wildlife habitat will not continue. This negative interaction between human and wildlife is also caused by other sources of stresses on natural resources in PAs as stipulated much by Hackel (1999); URT (2002); Johansen (2002) and Kideghesho (2005).61

Sources of stress |

Strength of stress |

Mean±Sd |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Very high |

High |

Medium |

Low |

Overall |

|

(a)Poverty/Low income |

34(56.7)1 |

26(43.3) |

0(0.0) |

0(0.0) |

60(100) |

1.65±1.02 |

(b)Ignorance |

2(3.3) |

35(58.3) |

12(20.0) |

11(18.3) |

60(100) |

2.75±0.88 |

(c)Income generation from natural products |

12(20.0) |

34(56.7) |

14(23.3) |

0(0.0) |

60(100) |

1.55±1.00 |

(d)Population increase |

1(1.7) |

37(61.7) |

21(35.0) |

1(1.7) |

60(100) |

1.50±0.91 |

(e)Sabotage |

0(0.0) |

10(16.7) |

21(35.0) |

29(48.3) |

60(100) |

2.58±1.20 |

(f)Uncontrolled burning |

3(5.0) |

23(38.3) |

20(33.3) |

14(23.3) |

60(100) |

1.25±0.82 |

(g)Interaction between wildlife and human/ livestock |

34(56.7) |

22(36.6) |

3(5.0) |

1(1.7) |

60(100) |

2.52±1.31 |

(h)Drought/Floods |

5(8.3) |

35(58.3) |

13(21.7) |

7(11.7) |

60(100) |

1.58±1.94 |

(i)Agriculture |

18(30.0) |

39(65.0) |

3(5.0) |

0(0.0) |

60(100) |

1.58±1.00 |

(j)Settlements |

6(10.0) |

13(21.7) |

38(63.3) |

3(5.0) |

60(100) |

3.03±1.21 |

(k)Banditry |

0(0.0) |

37(61.7) |

11(18.3) |

12(20.0) |

60(100) |

2.13±0.85 |

(l)Lack of land use plans |

2(3.3) |

0(0.0) |

18(30.0) |

40(66.7) |

60(100) |

2.97±1.25 |

Table 9 Sources of stress on natural resources in Selous-Niassa TFCA

1Figures outside and inside the parentheses are frequencies and percentages respectively.

Wildfires

Control of wildfires is one among the strategies for conservation of biodiversity and other wildlife. During focus group discussion in study villages, it was found to have very few people adopt strategies/practices to control loss of wildlife resources. The area is the migratory route for migrating elephants and other animals. Wildfires occur frequently in the area. The major causes of these fires are honey mongering, charcoal production, clearance for cultivation and local beliefs. Wildfires have overwhelming effects on the biodiversity and ecology of the Selous-Niassa TFCA ecosystem thereof calls for efficiency and effective management especially when occurred at the wrong season.

In Nanyumbu and Liwale districts more than eight wildfires reported each year in different villages within Selous-Niassa TFCA. Figure 4 shows reported incidences of wildfires from 2010-2015. The extent of damage to Selous-Niassa TFCA is immeasurable but core PAs of Selous GR, Msanjesi GR, Lukwika-Lumsule GR, and some of forest reserves have natural firebreaks which are rivers(Matandu, Liwale, Mbwemkulu, Lumesule, Lukwika, Ruvuma etc) and man-made breaks includes roads. Availability of by-laws for preventing wildfires were aware to many villagers but traditional ways of starting the fire is unavoidable as mostly done at night hours.

Socio-economic factors influencing people encroaching Selous-Niassa TFCA

In this study, socio-economic factors influencing people encroaching of Selous-Niassa TFCA were strived to reveal their significance statistically. Towards revealing the statistically significance of socio-economic factors influencing encroachment of Selous-Niassa TFCA, a multiple regression model was employed. The socio-economic factors revealed in the study area were entered sequentially in the multiple regression model, checked and the insignificant factors were removed from the prediction model. The explanatory variables that were accommodated in multiple linear regression model were; age, sex, education level, household size, household income, years lived in a village and land size owned by a household. The model was purposely employed to assess the significant socio-economic factors influencing encroachment of natural resources in the study area.

Results of the multiple regression model

The multiple regression models were used to determine the effects of explanatory variables on encroachment of natural resources in the study area. The model summary in Table 10 shows that the independent variables fit well in the regression model in that R square was 0.537.This means that the fit explains 53.7% of the total socio-economic factors influencing people encroaching wildlife corridor were explained by the tested factors. The R and adjusted R2 of 0.773 and 0.475 respectively show that there is correlation between encroachment and explanatory variables.

Model |

R |

R Square |

Adjusted R2 |

SE |

|

0.773 |

0.537 |

0.475 |

0.226 |

Table 10 Model summary for socio-economic factors influencing encroachment of Selous-Niassa TFCA

The model reveled ANOVA results as follows, with F value of 8.621 estimated at 11 and 78 degrees of freedom and a standard error of 0.226, gave a p value of 0.000 (Table 11). This implies that at a significance level of 5% the explanatory variables are statistically significant in explaining the involvement in encroachment of TFCA.

Model |

Sum of Squares |

Df |

Mean Square |

F |

Sig. |

Regression |

3.08 |

11 |

0.44 |

8.621 |

0 |

Residual |

2.654 |

78 |

0.051 |

|

|

Total |

5.733 |

89 |

|

|

|

Table 11 ANOVA for socio-economic factors influencing encroachment of Selous-Niassa TFCA

Table 12 summaries the socio-economic factors influencing encroachment of Selous-Niassa TFCA. The result shows that, some explanatory variables influences encroachment of the Selous-Niassa TFCA significantly. Of the seven independent variables used in the model only three variables are significant at 5% significance level (α).

Model |

B |

Std. Error |

Beta |

T |

Sig |

(Constant) |

0.827 |

0.254 |

|

3.251 |

0.002 |

Age |

-0.01 |

0.028 |

-0.038 |

-0.359 |

.721NS |

Sex |

0.153 |

0.068 |

0.247 |

2.25 |

.029* |

Education level |

-0.026 |

0.031 |

-0.095 |

-0.863 |

.392NS |

Household size |

0.061 |

0.043 |

0.14 |

1.409 |

.165NS |

Household income |

0 |

0.021 |

0.002 |

0.017 |

.986NS |

Years lived in a village |

0.161 |

0.059 |

0.275 |

2.719 |

.009* |

Size of land owned |

0.484 |

0.07 |

0.706 |

6.894 |

.000* |

Table 12 Multiple regression results for socio-economic factors influencing encroachment of Selous-Niassa TFCA

*Statistically significant at α=0.05; NS, statistically not significant at α=0.05

Sex

The results in Table 12 suggest that sex of household head influence encroachment of Selous-Niassa TFCA positively and significantly (b=0.153, p<0.05). This implies that males are exponentially engaged with encroachment activities like commercial poaching, logging, mining, charcoal making, extensive crop faming, livestock keeping and others compared to females who concentrates with subsistence farming, fuelwood collection. The results concur with Ntongan et al.50 and Noe.60

Years lived in a village

Respondents’ years lived in a study village influence encroachment of Selous-Niassa TFCA positively and significantly (b=0.161, p<0.05) (Table 12). This implies that, those respondents’ stays longer in a village equipped with indigenous technical knowledge and experience in wildlife migrations seasons, routes used, species involved and different valued Miombo trees species location and concentrations. The situations accelerates sabotage of the respondents with poachers and businessmen comes outside the district for illegal harvesting of natural resources within Selous-Niassa TFCA as explained much by Pimbert & Pretty,63 Mbwambo,59 and Pesambili.49

Size of land owned

Findings also revealed that size of land owned by a household influence encroachment of Selous-Niassa TFCA positively and significantly (b=0.484, p<0.05) (Table 12). This implies that as household size increases also size of land owned by a household need to be increased so as to supplement the need of increased members as a result of encroaching Selous-Niassa TFCA. An explanation behind the observed relationship is that the encroaching land within Selous-Niassa TFCA for livelihood is violating village land use plan and extended area for food production, building materials, settlement area and other socio-economic activities which hamper biodiversity conservation and ecosystem services of fauna and flora as supported much by Pinter-Wollman.60

Property damage and human life caused by wild animals

Protected areas in Tanzania are not fenced thus wildlife freedom of movement is almost boundless. However, climate change and variability accelerate the movements due to animals’ searching for their climatic niche. District Councils have a duty to combat dangerous animals and assist farmers in crop protection. Many Districts are understaffed and not adequately equipped to perform this duty.64 People who share the immediate boundaries with protected areas incur costs inflicted by wildlife conservation. Such costs include; loss of access to legitimate and traditional rights, damage to crops and other properties, livestock depredation, and risk posed to people’s lives through disease transmission and attacks by wild animals.

Out of the strategy used to minimize property damage and loss of life is the use of game scouts. Liwale District has seventy six (76) villages; Nachingwea District has 127 villages and Nanyumbu District have 93 villages. Over 50% of these villages experience human wildlife conflict (HWC). This is due to the fact that there are few game scouts distributed whereby only seven game scouts are in Liwale and distributed in seven villages include Lilombe, Mkutano, Liwale Mjini, Mirui, Mpigamiti, Nangano and Mlembwe (Liwale District Council report, 2017) while Nanyumbu have only one game scout (Nanyumbu District Council reports, 2017).

During interview with Liwale DGO; it was found that, low knowledge of district game scouts on non-lethal deterrents needed to be used for controlling problematic animals accelerate shooting of animals. These game scouts undergo short courses in wildlife management before they resume their duties. However these courses are inadequate. For years 2008 - 2015, eastern Selous-Niassa TFCA experienced fourteen (14) problem animals killed and other one hundred thirty four (134) injured. Most of the injured died and increase the mortality of wild animals (Table 13). Also, sixty seven (67) people were injured and forty two (42) people killed and mostly by elephant and crocodile; a total of 322.5 acres of different crops were destroyed as shown in Table 14‒16, respectively. Furthermore, a total of 63 livestock killed by wild animals in Selous-Niassa TFCA from 2011 – 2014 (Table 17).

S/N |

Type of animal |

Killed |

Injured |

1 |

Elephant (Loxodonta Africana) |

12 |

129 |

2 |

Hippo (Hippopotamus amphibius) |

2 |

5 |

Total |

|

14 |

134 |

Table 13 Problem animals killed or injured by game scouts in Eastern Selous –Niassa TFCA 2008 – 2015

Source: LDC office (2017)

Year |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

Total |

Number of injured people |

2 |

14 |

29 |

11 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

67 |

Table 14 People injured by dangerous animals in Eastern Selous –Niassa TFCA 2008-2015

Source: LDC & LLM office (2017)

Year |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

Total |

Number of killed people |

2 |

9 |

14 |

7 |

3 |

1 |

4 |

2 |

42 |

Table 15 People killed by dangerous animals in Eastern Selous –Niassa TFCA2008-2015

Source: LDC, NDC & LLM offices (2017)

S/N |

Type of Crop |

Type of Animal |

Acreage |

1 |

Cashewnuts (Anacardium ocidentale) |

Elephant |

48 |

2 |

Maize (Zea mays) |

Elephant |

75.5 |

3 |

Sorghum (Sorghum vulgare) |

Elephant |

70 |

4 |

Rice (Oryza sativa) |

Elephant and Hippo |

34 |

5 |

Cassava (Manihot esculenta) |

Elephant |

49 |

6 |

Sesame |

Elephant |

18 |

7 |

Banana (Musa sp) |

Elephant |

20 |

8 |

Sugarcane |

Elephant |

2 |

9 |

Sweet potatoes |

Elephant |

5 |

Total |

|

|

322.5 |

Table 16 Extent of crops damaged by wild animals in Eastern Selous –Niassa TFCA 2008-2015

Source: LDC & NDC offices (2017)

S/N |

Type of Livestock |

Quantity |

Type of animal |

1 |

Cattle |

1 |

Lion |

2 |

Goat |

53 |

Lion and Hyena |

3 |

Pig |

9 |

Lion |

Total |

|

63 |

|

Table 17 Livestock killed by wild animals in Selous-Niassa TFCA 2011-2014

Source: LDC and NDC offices (2017)

The wildlife policy of 2007 statement unlike the previous one (of 1998) has failed even to give short-term and long-term strategies to address the human-wildlife conflict and instead the government is now trying to assign the responsibility to CBC institutions.55 Tanzanian government has introduced a compensation scheme for crop damage not exceeding five acres and consolation for human injured/killed by wildlife whereby the consolation does not exceed one million Tanzania shillings. The Government will devolve progressively the responsibility for Problem Animal Control (PAC) to operating Community Based Conservation (CBC) programmes and continue to give assistance where village communities have not developed this capacity (WPT, 2007).

The government shifts wildlife management from Decentralisation (according to WPT, 1998) to Recentralisation (according to WPT, 2007). Liwale, Nachingwea and Nanyumbu Districts are not distinguished from this scenario as it has eight (8) villages out of seventy six (76); nine (9) out of one hundred and twenty seven (127) and nine (9) out of ninety three (93) in Liwale, Nachingwea and Nanyumbu Districts respectively forming CBC (WMAs). Thereof this approach is likely to exacerbate the problem for two reasons. First, there are few CBCs in areas where humans live with wildlife countrywide and where these institutions exist they are still in futile and/or ineffective. Second, the institutions lack both human and finance capacity to deal with this sensitive and long-standing problem (ibid).

Furthermore, Sections 71 of Wildlife Conservation Act No. 5 of 2009 gives power to the Minister of MNRT make regulations specifying the amount of money to be paid as consolation to a person or groups of persons who have suffered loss of life, livestock, crops or injury caused by dangerous animals as stipulated much in Wildlife Conservation of Tanzania (Dangerous Animals Damage Consolation) Regulations (2011). Likewise, the Act considered only dangerous animals such as lion, buffalo, elephant and other animals categorized in fourth schedule for consolation of life, crops or injury while problems animals are not considered for this while contribute to crops destruction, injury or loss of life (URT, 2009).

Conclusion

The study demonstrated consequences of climate change and variability that affect management of Selous-Niassa TFCA, includes; access to land in study area which is possible and unreserved land is fairly not enough compared to population available. However, gender inequality experienced especially to women who are continued to be discriminated and denied direct access to land and insecure. Though, the land in the study villages undergo land use plan, thereof land accessed by the community is mainly the one that planned for agriculture. Shifting cultivation is still practiced in the study area and need to be reversed so as communities adopt best agriculture practices that will use small farm plots which will be well mechanized in terms of pesticides, insecticides and fertilizers application.

The study area suffered from wild animals that destroy crops but adoption of application of non-lethal deterrents has become the best control measure. Also, conservation agriculture which is the new phenomenon in the study area needs to be emphasised to be adopted quickly so as to protect biodiversity and land degradation resulting from deforestation. This will also lower pressure to wildlife destruction. Poaching, encroachment for fuel wood and wildfires cause wildlife habitat destruction and decrease of wildlife population as a result those direct and indirect benefits of wildlife resources in the ecosystem will be destroyed. Therefore, integrative participatory approach of local people and other stakeholders in relation to wildlife resources management and environment as a whole is vital in order to come up with collaborative sustainable wildlife management network in the TFCA ecosystem.

Generally, benefit-based approaches is a fundamentally inconsistent due to the fact that, their design and implementation can hardly enhance the value of the wildlife to local people but cannot ensure equity access and cannot guarantee sustainability of the benefits to local communities. Therefore, the current benefits are less effective in inspiring sustainable conservation behaviors. This, however, does not mean that the PAs in Selous-Niassa TFCA should abandon the benefit-based approaches and return to the ‘fences and fines’ approach. More comprehensive and integrated study that will offer more innovative and effective options in view of making the initiatives more conceivable is vital. The options should seek to increase more opportunities that will divert the communities from heavy reliance on wildlife species and habitats for survival.65‒78

Recommendations

The government in collaboration with other stakeholders should:

I am heartily thankful to my employer (The Mwalimu Nyerere Memorial Academy) for giving me permission to undertake this research; my co-authors who also are my research supervisors, Dr. Josephat Saria and Yohana Lawi from Faculty of Science, Technology and Environmental Studies of the Open University of Tanzania whose encouragement, guidance and support from the initial to the final level enabled me to develop an understanding of the research subject into practice. Their sage advice, insightful criticisms, and patient encouragement aided the writing of this research in innumerable ways. Lastly, I offer my regards and blessings to all of those who supported me in any respect during the completion of my research.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

©2018 Zella, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.