Advances in

eISSN: 2378-3168

Review Article Volume 2 Issue 6

1Loyola University Chicago, USA

2Department of Dietetics Education Programs, Loyola University Chicago, USA

Correspondence: Elizabeth Sommer H, Registered Dietitian, Loyola University Chicago, 2828 N Pine Grove Avenue APT 417, Chicago, IL, 60657, USA, Tel 2484105650

Received: April 16, 2015 | Published: July 31, 2015

Citation: Sommer E, Kouba J. Impact of food justice education on health behavior change in youth. Adv Obes Weight Manag Control. 2015;2(6):129-139. DOI: 10.15406/aowmc.2015.02.00038

When it comes to the etiology of obesity among overweight and obese youth, an increasing amount of evidence-based research has shown that barriers to health behavior change may stem from social and environmental injustice rather than individual eating habits and food preferences. Engaging youth in obesity prevention advocacy efforts through skill development, education and behavior and attitude changes with the purpose of persuading others to take action holds promise as a way to increase the demand for policy changes to improve nutrition and physical activity. The food justice movement aims to challenge and restructure the food system, reduce disparities among those most vulnerable and establish a strong advocacy network within those communities. In this comprehensive literature review, we summarize published research that illustrates how the current obesogenic environment can be attributed to imbalance in the food system, which has lead to unequal access, availability and affordability of healthy food; we provide a systematic review of the prevalence of obesity among higher-income, non-Hispanic white children and adolescents compared to the dietary intakes of lower-income populations (specifically African American and Hispanic populations) to demonstrate that dietary intake disparities, in relation to income and race, have not improved over time; we discuss current public health research that indicates that preventing obesity in youth requires a comprehensive, societal, school-based approach through interventions that involve the individuals, families and communities in need and we outline a guide for the use of food justice education as a promising strategy to empower youth as obesity prevention advocates while also inciting health behavior change in themselves and their peers.

Keywords: childhood obesity, prevention, food justice education, community nutrition, youth advocacy

DHHS, department of health and human services; NHANES, national health and nutrition examination survey; CINAHL, cumulative index of nursing and allied health; HFCS, high fructose corn syrup; ADM, archer daniels midland; CDC, centers for disease control and prevention; PedNSS, pediatric nutrition surveillance system; MMWR, morbidity and mortality weekly report; HEROES, healthy, energetic, ready, outstanding, enthusiastic, schools; CSH, coordinated school health approach; CRM, community readiness model; CLOCC, consortium to lower obesity in Chicago children

In the year 2000, the United States Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) released and monitored a list of health objectives, known as the Healthy People 2010 goals to guide the nation’s health promotion and disease prevention efforts. One of several targets for better nutrition and more-active lifestyles was the goal of reducing the percentage of children and adolescents who are obese to 5%-- the level observed in the early 1970s.1 Despite the launch of numerous policy-and community-level initiatives as a result of setting this goal, it became clear that a 5% target was too ambitious, which is why in November 2010, the Healthy People 2020 objectives were released including the more modest objective of “reducing the prevalence of obesity by 10% from 2005-2008 levels among youth aged 2-19years-to bring overall prevalence down to 14.6% by 2020”.1 A groundbreaking report by Ogden et al.,2 used data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2009-2010 to show that the prevalence of childhood obesity increased in the 1980s and 1990s but there were no significant changes in prevalence between 1999-2000 and 2007-2008 in the United States.2 Furthermore, in 2009-2010, the prevalence of obesity in children and adolescents was 16.9% indicating trends have remained stable when compared to 2007-2008.2

Despite the encouraging nature of evidence for recent stabilization, there is now a tremendous amount of pressure to identify the most effective intervention and prevention strategy for reversing this nationwide epidemic, particularly for those non-Hispanic black and Hispanic children and adolescents for whom the prevalence of obesity continues to be the highest.2 On the heels of these efforts, the food justice education movement has emerged as a promising approach to improve the health of future generations by harnessing the power and enthusiasm of youth to advocate for food justice, or, the right of all communities to grow, sell and eat healthy food-regardless of socioeconomic status or race. The idea of using food justice as a curriculum to engage youth in obesity prevention advocacy efforts that aim to improve health by targeting environment and policy change is a more recent innovation. The food justice movement has been growing in theory and support over the past decade.3

In the book, Food Justice, written about the emerging movement, co-authors Gottlieb & Joshi4 defined food justice as related to three key areas for action: the food system, health disparities and community partnerships. All involve stakeholders on the individual, community and policy-making levels. The food system, or the way food gets from the farm to one’s plate, includes the production, distribution, marketing, preparation, consumption and disposal of food. The challenges surrounding the food system occur when the power-players or major food corporations, exert their power and influence over the policies that control the food system thereby influencing one’s access to and availability of healthy food. Healthy food can be defined as food that is affordable, has nutritional value, is safe to eat and often times is locally-grown in a manner that considers the well-being of the land, workers and animals.5

In the following sections, we summarize published research that illustrates how the current obesogenic environment can be attributed to imbalance in the food system, which has lead to unequal access, availability and affordability of healthy food; we provide a systematic review of the prevalence of obesity among higher-income, non-Hispanic white children and adolescents compared to the dietary intakes of lower-income populations (specifically African American and Hispanic populations) to demonstrate that dietary intake disparities, in relation to income and race, have not improved over time; we discuss current public health research that indicates that preventing obesity in youth requires a comprehensive, societal, school-based approach through interventions that involve the individuals, families and communities in need and we outline a guide for the use of food justice education as a promising strategy to empower youth as obesity prevention advocates while also inciting health behavior change in themselves and their peers.

The objective of this review was, initially to answer the following question: in low-income communities, do multi-component, school-based programs, which raise awareness about the circumstances that contribute to a lack of access to healthy, fresh foods, have a positive contribution to students’ overall knowledge, attitude and behaviors towards improving their health? To do this, we started by separating the research into three groups:

Study |

Design |

Sample/Setting |

Intervention |

Outcome Measures |

Summary of Results |

Community case study |

Sample: 22 students from Omaha South Magnet High school were chosen to be in the cohort of youth advocates for obesity prevention. Setting: underserved Latino community in Omaha, Nebraska |

Phase 1: train a cohort of youth to provide them with advocacy skills and awareness of obesity prevention. Phase 2: the youth cohort created and launched the Latino health movement, SaludableOmaha |

At baseline, the community readiness model was used to assess the community’s readiness to change by interviewing parents and community leaders and scoring their readiness to address childhood obesity. |

South Omaha community is at a low stage of readiness to address childhood obesity. Using a youth-driven approach to advocacy, the SaludableOmaha project generated community-relevant sustainable solutions. |

|

Funders’ collaborative results report featuring an external evaluation and an internal review of the Regenerations: Healthy Communities project, provided to the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. |

Sample: 12 youth organizing groups. Setting: at-risk communities throughout the United States. |

Funders’ Collaborative on Youth Organizing selected 12 youth organizing groups and supported them with technical assistance and funding as they advocated for access to healthy, affordable food in their schools and communities. |

Imoyase Community Support Services of Los Angeles was contracted by the Funder’s collaborative for a project evaluation. Data on grantee characteristics, political education efforts, leadership development, and outreach and recruitment strategies was collected and analyzed to provide a summary of key findings. The data covered five time periods that ranged from three to five months each in 2011 and 2012. |

Seven of the 12 grantee organizations achieved specific policy victories. Three of the 12 groups achieved important policy benchmarks. Two of the 12 groups increased their visibility as stakeholders in their communities’ efforts to fight the obesity epidemic. |

Table 1 Food justice education research

The U.S. food market provides ~3900 calories per capita each day, or twice the average person’s caloric requirement. Between 1970 and 2000, the average per person consumption of added fats increased by 38%, whereas that of sugars increased by 20%. The consumption of high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS) alone increased more than 1000% between 1970 and 1990 and today accounts for more than 40% of caloric sweeteners added to food and beverages. This excessive intake of fats and sugars is worsened by the availability of extremely cheap calorie options.6

Research has indicated a clear relationship between obesity and the consumption of cheap commodities, namely added fats, sugars and refined grains. In addition, it is well known that the three leading causes of death in the United States-heart disease, cancer and stroke-are all associated with poor diet and being overweight.6 Government-issued agricultural subsidies are worsening obesity trends in America: excluding the poorest of the poor, obesity is associated with poverty.6. It cannot be denied that the current agricultural policies in the United States have a direct contribution on the overall poor health of Americans. Government-issued subsidies that have skewed agriculture markets away from agro-ecological development and steered them towards the overproduction of commodities that are the basic ingredients of highly-processed, low-nutritional value, energy-dense foods.6 As the main federal mechanism for influencing American agriculture, the 2013 Farm Bill was of great importance to consumers who need to understand the implications of policies that will shape the nutritional environment for the next five years.

In the year of 2010, the United States saw record levels of hunger throughout the nation. Unfortunate as this is, it was the catalyst for a great transformation of the food movement which caused the spotlight to shine on hunger and food access in the United States, driving up local food production and improved policies from the federal to the local level.7 Since then, our economy has struggled to make these initial changes permanent due to the global food and financial crises of 2007-2010 and the difficulty associated with protecting against the concentration of agrifood monopolies like Monsanto, ADM, Cargill and Walmart. The movement to improve access to healthy food in low-income urban communities has received a high level of support from the White House and the USDA. But according to a report from the Institute of Food and Development Policy, “no amount of fresh produce will fix urban America’s food and health gap unless it is accompanied by changes in the structures of ownership and a reversal of the diminished political and economic power of low-income, people of color”.7 This statement reinforces the need for progressive programs that approach the food crisis in a way that creates a generation of food sovereignty advocates who believe that every citizen has the right to food that is sustainably produced, locally sourced and agro-ecologically developed. While the causes of nutritional disparities among undeserved communities go beyond the location of grocery stores, the effort to improve access and availability of healthy foods at the local level should not be ignored by any means. Agricultural policy dictates which crops the government will financially support the growth of and in turn, which crops U.S. farmers will grow thus determining the prices of those crops. Public advocacy for policies that support the subsidization of those crops that translate into healthy food production and availability could be the most widespread preventive measure to combat the obesity epidemic.6

Moving health-promoting policies forward proves to be a challenge when many argue that the current state of American agricultural policy is backwards. For example, when national target farm prices drop below a given market threshold, government subsidies are awarded to producers based on their farm’s historical yield thus providing strong incentives for overproduction in a climate of low market prices.6 Furthermore, the government has traditionally failed to offer incentives or support for fruit and vegetable production and, even worse, farmers are typically penalized for growing specialty crops if they have received federal subsidies to grow commodity crops. According to the U.S. General Accounting Office, “in 2001, large farms, which constitute 7% of the total, received 45% or federal subsidies, whereas small farms, constituting 76% of the total, received 14% of total payments”.6 The disproportionate allocation of subsidies to large farms has resulted in fewer farms and diminished agricultural diversity, which has made it difficult for small, bio-diverse farms to thrive.6 This has led to a significant debate among experts over whether or not agricultural subsidies have an impact on the prevalence of obesity.6 While this is a highly complex, multi-factorial issue, one argument stands out: those who argue for government-funded subsidization have remarked that because the share of commodity ingredients in the retail price of the foods that contain them is relatively small, cheap commodities cannot meaningfully contribute to the typically lower-cost retail prices of those foods. Furthermore, data examining food market trends has indicated that food consumption patterns do not usually change significantly in response to small price changes.6 In response to this argument, those against the government subsidization of unhealthy commodities responded that although the share of commodities in the retail price of food may be small, it is problematic to focus solely on consumer behavior in response to price change.6

Real votes in agricultural policy are required to incite real change in the American food system. Because this opportunity only presents itself every 5-7years when a new farm bill is drafted, it is crucial that youth become involved in advocacy efforts for those policies which support sustainable agriculture that yields bio-diverse, quality foods that are produced in ways that optimize the use of nonrenewable resources. With the long-awaited passage of the 2013 farm bill, those in poverty can expect their situation to worsen in the coming decade due to the $8billion cuts in food stamps while farmers can breathe a sigh of relief with crop insurance for farmers being expanded by $7billion.8 While the bill’s inclusion of a pilot program to encourage recipients of food stamps to buy more fruits and vegetables is a step in the right direction, it is clear that advocacy over the next decade is needed for policies that support the local food system as well as those research and development initiatives that support public health goals rather than goals driven by economic profit.6

The Social justice perspective

When examining the etiology of the obesity epidemic, it is important to acknowledge how clinicians’ have treated the overweight and obese populations in the past. Until recently, the medical model was thought to be the best approach to treating overweight and obese patients. The medical model, a standard in western medicine, emphasizes a focus on the individual patient as the best way to target and treat specific health behaviors. While this approach has been successful in some cases, it clearly has a limited impact when it comes to health behavior change in youth. According to Adler & Stewart,9 “the medical model views individuals as responsible agents, capable of acting in their own behalf. The main purpose of interventions regarding overweight and obesity, along with other behavioral risk factors, is providing information so that people can make more informed behavioral choices”.9

In contrast, the public health model not only places its strongest emphasis on prevention but also takes into consideration a range of factors that could potentially contribute to the problem. Arguably one of the most important factors is the obesogenic environment, to which the public health model assigns responsibility for the obesity epidemic in comparison to the medical model which tends to assign blame to the individual whose caloric intake is greater than caloric expenditure.9 Aspects of both models can be used to create a more effective, proactive solution to this issue: the social justice perspective facilitates a synthesis of both models and highlights the idea that while it is the individual’s responsibility to maintain a healthy lifestyle, they can only be held accountable for changing their behavior if they have access to the resources which will allow them to do so.9

The complement to social justice is environmental justice, defined by Bullard & Johnson10 as “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income with respect to the development, implementation and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations and policies”.10 Evidence has revealed that grass-roots activism among people of color and low-income persons has proven to produce groups of organized, educated and empowered individuals who seek to improve the way health and environmental policies are administered.10 Even more compelling is the argument for engaging youth in grassroots activism to prevent obesity by promoting health and wellness. This is based on two facts:

A progressive movement towards health behavior change and a more equal distribution of power in the food system is on the horizon. Using the principles of the social-justice perspective combined with evidence gathered from a history of environmental injustice among low-income communities of color, it is possible to motivate youth to become engaged and active advocates for a healthier community. In order to identify a foundation for education on the social and environmental injustices within system, the factors that contribute to the obesogenic environment must be identified.

Factors that contribute to the obesogenic environment

The environmental and socio-economic factors that contribute to the obesogenic environment are numerous and complex. Based on the current available literature, the following key environmental and socio-economic factors were identified as significant contributors to food injustice in low-income communities: nationwide health disparities, inequalities among communities’ access to and availability of healthy food and advertisement trends among adolescents. It should be noted that a wide variety of childhood obesity intervention targets have been investigated including physical activity and access to healthcare. While a discussion of these additional factors will be included, they are not the primary focus of this study.

Disparities among obese children based on income and race/ethnicity: With the majority of the food system being influenced by a minority of agrifood corporations-the role of the environment in the pathogenesis of the obesity epidemic has become a research trend in the field of public health.4 Under great scrutiny is the existence of nationwide health disparities based on ethnicity and income, specifically among children and adolescents. While an objective of this review is examining disparities among youth, it is also important to mention the dietary intake patterns of adult Americans who set an example for younger generations. One note-worthy study conducted by Kirkpatrick et al.,11 examined dietary intake data taken from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), conducted from 1971-2002. When identifying the predominant dietary intake pattern among adults, it is important to point out that the highest rate of adherence to food group recommendations was among those in the highest income group with a significant gap between percentage of adherence in the middle and low-income groups.11

This disparity can be seen when looking at the percentage of adults aged≥19years whose usual intakes of total vegetables were equal to or above the minimum recommended amounts: 15.5% of the highest income group population (poverty ratio≥1.86) had adequate total vegetable intake, while only 7.7% of those in the lowest income group (poverty income ratio≤1.30) met the recommended minimum amounts. It is curious that among children, the findings were more erratic with smaller proportions of children in the highest income group compared with other income groups meeting the recommendations for certain food groups.11 In regards to ethnicity, the greatest disparities can be seen in the analysis of dietary intake patterns of specific populations-particularly non-Hispanic black children-when compared to non-Hispanic white children. Overall, smaller proportions of non-Hispanic black children met the minimum recommendations for whole fruit, orange and other vegetables, total grains and milk when compared with non-Hispanic white children, regardless of income level.11 In the context of the obesity epidemic, while childhood obesity prevalence may have stabilized, evidence has shown that dietary intake disparities, in relation to income and race, have not improved over time.11

Ethnicity and income have been recognized as environmental factors that contribute to the childhood obesity epidemic, yet while these two factors have an intertwined relationship with obesity prevalence; their individual contributions to the problem remain under investigation. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s Pediatric Nutrition Surveillance System (PedNSS) data, “the prevalence of obesity was 14.4% among children aged 2 through 4years living in low-income families in 2010”.12 Even more startling is data from NHANES, which indicates that in 2009-2010, 12.1% of the US children aged 2 through 5years, were obese.12 To understand and analyze the incidence and reverse of obesity among low-income children, the PedNSS was used to examine these trends in 2010-2011.

The startling results indicated that the incidence of obesity was 11.0% among children aged 0 to 23months at baseline living in low-income families; among this low-income population, disparities between subgroups exist based on race/ethnicity. For non-Hispanic white children aged 0 to 23months, the incidence of obesity was 9.3%; in comparison, those children aged 0 to 23months from the Hispanic subgroup had a 13.1% incidence of obesity.11 Overall, the risk of becoming obese was higher and the proportion of obesity reversal was lowest between Hispanic and American Indians/Alaskan native children than among children in other racial/ethnic groups.12 Based on this data, childhood obesity prevention strategies should focus on interventions that: increase adherence to recommended dietary intakes of certain food groups (fruits, vegetables and whole grains) in non-Hispanic African American children, reduce the incidence of obesity among Hispanic children and advocate for policies that make healthy food more affordable to reduce the health disparities between income groups.

Affordability of healthy food: An individual’s access to affordable, nutritious foods is often influenced by factors that affect cost. According to Azetsop & Joy,13 affordability refers not only to income, but also the price of healthy foods in relation to unhealthy foods, the price of services that influence the price of healthy foods (such as transportation) and external factors (taxes, subsidies).13 The capitalist mentality that food should be commoditized has created a food environment that focuses on marketability instead of nutrition. Like health care, food should be equally accessible and affordable for all human beings-regardless of socioeconomic status or race. Research has shown that manipulation of cost can lead to increased healthy food consumption.13 Recently, policy proposals have focused on the implementation of sales taxes for unhealthy foods and subsidies for healthy food consumption as a means to promote healthy eating with the overall goal of reducing health-care costs associated with the treatment of nutrition-related chronic illnesses.13 While this seems like a simple solution to a nation-wide problem, the discrepancies involved are numerous: i.e. how does one classify a food as unhealthy, particularly when those low-income individuals who rely on federal food assistance live in food deserts, otherwise known as a geographic area where affordable and healthy food is difficult to obtain. In addition, consumer preference also has a major impact on the sale of certain unhealthy items. Many of these calorie-dense items are low-cost and while they may taste good, most of the time this is because these items are high in fat, sugar and salt. One study14 reported 50% fewer convenience stores near (within 0.5miles) schools in high-income census tracts than in low-income census tracts.15

While racially mixed census tracts contained 19% more convenience stores near (within 0.5 miles) schools than predominantly white census tracts.15 This is a classic example of food injustice: based on the aforementioned data, it can be assumed that students in the high-income census tracts are faced with less temptation to consume high-calorie, low-nutrition foods due to the lack of convenience stores near their school. This is where the food systems component of food justice education comes into play. If adolescents from low-income communities could be educated on the benefits of healthy eating along with the injustice of the disproportionate availability of fast food and junk food items that are also marketed towards their demographic; perhaps their consumer sensibility and food preferences may differ. Regardless of consumer food preference, the conundrum occurs when convenience stores like 7-Elevenâ sell fresh apples for 99 cents each while more popular items like ‘mini tacos’ are sold four for $1.00. For children and adolescents who have $1.00 to spend on an after school snack, it is unlikely that they will choose one item when they could purchase four items for the price of one.

Access to healthy food: In a review by Larson et al.,14 the relationship between neighborhood access to healthy foods and dietary intake and the relationship between neighborhood access to foods and weight status was examined.14 Using a snowball strategy to identify relevant research studies, 54 articles were completed in the United States and published between 1985 to April 2008 that met the inclusion criteria relevant to the review objectives. The articles included provided accurate evidence-based research regarding

The findings of Larson et al.,14 were significant and in general, suggested that neighborhood residents who have better access to supermarkets and limited access to convenience stores tend to have healthier diets and lower levels of obesity.14 Furthermore, residents who have better access to full-service restaurants and greater cost barriers to fast-food consumption have healthier diets and lower levels of obesity.14 Despite various limitations that included the validity and reliability of measures, completed studies examined in this review indicate a need for policy action and other intervention strategies to ensure equitable access to healthy foods across the United States.14

Adolescent exposure to televised food advertisements: After careful analysis of trends in exposure to televised food advertisements among children and adolescents in the United States, the Institute of Medicine concluded that there is strong evidence for children aged 2-11years that television advertising influences short-term food consumption and increased television watching promotes sedentary behaviors that can continue into adulthood.16 A study by Powell et al.,16 examined the trends in children and adolescents’ exposure to food advertising in 2003, 2005 and 2007, including separate analyses by race. Their results indicated that in correlation with the upward trend in total energy intake derived from fast food outlets, adolescents were exposed to fewer food advertisements compared with younger children, with fast food instead of cereal as the most prevalent ads.16 Further analysis of this data revealed that in 2007, all teens aged 12-17, saw an average of 4.1 fast-food advertisements per day, white teens in the same age category saw an average of 3.8 fast-food advertisements per day while black teens saw an average of 5.5.16 While this data is not an accurate indication of advertising trends today, it reveals how disparities in marketing may have contributed to the current health disparities based on race/ethnicity.

When examining trends in overall exposure to food advertisements, a number of positive changes have occurred. For example, from 2003-2007, the number of food ads daily fell by 13.7% and 3.7% respectively among children aged 2-5 and 6-11years.16 However, continued monitoring of children’s exposure to food advertising through the ever expanding internet and other modern media markets is crucial to understanding the extent to which individual will-power can translate into a reduction in the promotion in unhealthy food products.16 In addition, the use of adolescents voices for regulatory calls requiring “good-for-you” advertising for healthy products only could lead companies to compete among each other to make their products healthier and more affordable using the effective persuasion techniques typically used to market unhealthy food for children.16 The need for adolescent advocates to promote and educate younger children on the dangers of succumbing to food advertising could prove to be a potential, promising strategy for change.

Comprehensive intervention for preventing obesity in children

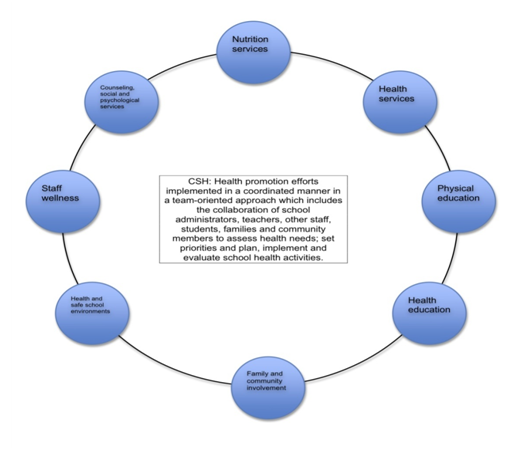

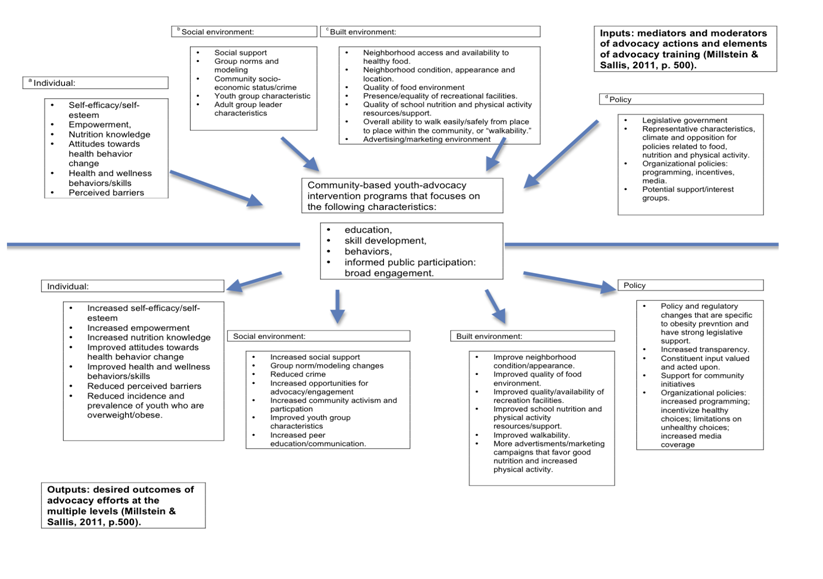

Together, the public health approach and social-justice perspective provide a strong basis for the continued research of obesity prevention programs that target the health, education and community care systems to achieve long-term sustainable impacts.17 The following review will provide an overview of the evidence-based research currently available that supports the use of multi-component, school-based and community-focused interventions to promote health behavior change in youth. In order to determine the most effective theoretical model that could possibly be used as a foundation for food justice education, the role of the conceptual framework used in each study will also be considered. Seen at the end of this report, Figures 1,2 & 3 correspond with the models that will be discussed in further detail and provide supplemental information and a visual representation of the coordinated school health approach (CSH) the community readiness model (CRM) and the youth advocacy model.

School-based interventions: In 2013, the Cochrane review of childhood obesity prevention research was updated to include an additional 36 studies (a total of 55 studies), which target obesity prevention efforts in children ages 6-12years old.17 The studies included in this review examined interventions that aimed to reduce adiposity and improve physical-activity related behaviors or diet-related behaviors. Overall, the authors of this study found strong evidence to support advantageous effects of childhood obesity prevention programs on BMI in school age children. Promising policies and strategies were those that improved healthy food access, availability and affordability in schools by promoting an environment that supports health and wellness but does not distract from the core curriculum.17 More specifically, Waters et al.,17 indicated the following to be the most promising policies and strategies for prevention and reversal of the childhood obesity epidemic:

This research shows that while there has been no shortage of effective interventions identified, there is a need for how further research, which shows how those interventions, can be entrenched within the health and education systems.

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s18 Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), published in September 2011 made significant updates to the previous guidelines for school health to promote healthy eating and physical activity. These guidelines were based on an in-depth review of the research and were developed in collaboration with a variety of health experts on the federal, state and local levels to present the paramount practices for healthy eating and physical activity in the public school system. Collectively, the nine guidelines emphasize that the best approach to prevent childhood obesity in schools is to make sustainable, environment-based changes that promote healthy eating and physical activity by encouraging community involvement and hiring individuals that will lead by example.18 While the actual term “food justice education” was not used anywhere in the MMWR, the report did mention the need to “advocate on behalf of students to create a healthy, safe and supportive school environment that allows students to make healthy dietary and physical activity choices both in and out of school”.18 Of particular importance is the indication that it is crucial that schools hire professionals who will fight to prevent childhood obesity and serve as advocates for schools to improve their policies and practices to reflect a mission of healthy eating and increased physical activity. As previously mentioned, the term “food justice education” was not used in the MMWR article; however, the current evidence implies if these adult advocates used food justice education as a method to teach their students how to be advocates within their schools and outside in their communities, their continued involvement could prove to be a more sustainable strategy for childhood obesity prevention in schools.

Despite the evidence-based research behind the CDC guidelines made easily available to the general public, there have been few intervention studies that explicitly use and evaluate these strategies. The HEROES (Healthy, Energetic, Ready, Outstanding, Enthusiastic, Schools) Initiative is a school-based coordinated childhood obesity prevention intervention that was developed to reduce the burden of childhood obesity in several states in the Midwest.19 This program aimed to reduce the burden of childhood obesity by using the strategies and guidelines developed by the CDC to evaluate and examine the impact of a coordinated school health (CSH) approach (Figure 1) on student-level outcomes. There were a total of 17 schools throughout Southern Indiana, Northwestern Kentucky and South Eastern Illinois who participated in this study (including elementary, middle, high schools; both public and private schools; and schools in rural and urban areas).19 The HEROES intervention aimed to facilitate health behavior change by changing the overall infrastructure of the school by providing substantial funding and implementing strategies tailored to each school’s individual needs and identity.19 Student level outcomes were based on physiological measurements (weight) and self-reported behavioral data (dietary intake data and amount of physical activity and screen time in a 24hour period).19 Most notable from this outcome data is the small but significant increase of .9% (p<.001) observed in the proportion of those students who were normal weight after the 18-month intervention; however no significant changes were observed in the proportion of students who were obese.19 This study demonstrates the efficacy of the coordinated school health approach as a promising strategy to prevent childhood obesity that would greatly benefit from the inclusion of youth justice education to improve the sustainability of interventions over time.

Community-focused interventions: In response to the many observational studies whose findings demonstrate an association between neighborhood attributes such as poverty and racial segregation and increased risks of obesity and diabetes (even after adjustment for observed individual and family-related factors), the United States Surgeon General has called for efforts to “create neighborhood communities that are focused on healthy nutrition and regular physical activity, where the healthiest choices are accessible for all citizens”.20 The built environment, or “the neighborhood characteristics and broader contexts of organizations, communities, states, countries”,3 is an important pathway through which changes (like the addition of grocery stores or recreational fitness facilities) might affect health-related behaviors and outcomes such as childhood obesity.20 A randomized social experiment by Ludwig et al. examined the association of randomly assigned variations in neighborhood conditions with obesity and diabetes to determine associations between neighborhood poverty level and indicators of chronic disease. The findings were significant and showed that the opportunity to move from a neighborhood with a high level of poverty to one with a lower level of poverty was associated with modest but potentially important reductions in the prevalence of extreme obesity and diabetes.20 This research emphasizes the possibility that advocacy for clinical or public health interventions that ameliorate the effects of neighborhood environment on obesity and obesity-related illness could generate substantial social benefits, particularly among youth and adolescents.20

The community readiness model’s stages of change (Figure 2) can be a useful tool for obesity prevention research because it provides a method for matching intervention efforts to the community’s readiness to change. In contrast to the transtheoretical model (focus on the individual readiness to change), the community readiness model emphasizes assessment of a community’s readiness to change, particularly in those communities that are under-served and under-represented.21

Stage 1: no awareness |

Issue is not generally recognized by the community or leaders a s problem (or it may not be an issue) |

Stage 2: denial/resistance |

At least some community members recognize that the issue is a concern, but there is little recognition that it might be occurring locally. |

Stage 3: vague awareness |

Most feel that there is a local concern, but there is no immediate motivation to do anything about it. |

Stage 4: preplanning |

There is a clear recognition that something must be done, and there may be a group addressing the issue. However, efforts are not focused or detailed. |

Stage 5: preparation |

Active leaders begin planning in earnest. Community offers modest support of efforts. |

Stage 6: initiation |

Enough information is available to justify efforts. Activities are under way. |

Stage 7: stabilization |

Activities are supported by administrators or community decision makers. Staff are trained and experienced. |

Stage 8: confirmation/expansion |

Efforts are in place. Community members feel comfortable using services, and they support expansions. Local data are regularly obtained. |

Stage 9: high level of community ownership |

Detailed and sophisticated knowledge exists about prevalence, causes, and consequences. Effective evaluation guides new directions. Model is applied to other issues. |

Figure 2 The community readiness model stages of change, based on the table found in Frerichs et al. 21

Note.The Community Readiness Model: a multifaceted tool used to identify gaps in community readiness and capacity; a theoretical framework and method for measuring a community’s readiness to address obesity prevention21

Results: synthesis of recent food justice education research

It is evident that there is a strong foundation of research supporting the potential impact of food justice education on health behavior change in youth, yet because of the relative novelty of this curriculum, the research that demonstrates the effectiveness of food justice curriculum as a singular intervention is scarce. The following section will discuss two relevant studies (Table 1) that examine the effect of obesity prevention interventions specific to food justice education and their impact on health behavior outcomes in youth.

For the purpose of reviewing the most current available literature, food justice education was defined as any community-based intervention that aims to teach youth one or more of the following objectives:

When it comes to the obesity epidemic, it often feels like the issue is a treadmill that health care professionals cannot get off: while trying to treat the myriad of co-morbidities associated with obesity in adults, it is difficult to move forward with prevention efforts focused on youth. Currently, efforts to increase healthy food intake among overweight and obese youth solely through nutrition education and food distribution has not been enough to reverse the obesity epidemic in this country. Research into the development and implementation of policies that focus on improvement of health disparities, food environment, consumer choice and marketing tactics is worthy of investigation. According to Holt-Giménez,7 the challenge for the food justice movement is to “address the immediate problems of hunger, malnutrition, food insecurity and environmental degradation, while working steadily towards the structural changes needed to turn sustainable, equitable, democratic food systems into the norm rather than a collection of projects”.7

Implications for professional practice

For registered dietitians, the spectrum of professional practice is immense due to the need for food and nutrition experts in the community, hospitals, schools and so much more. But no matter what career path an RD chooses to pursue, obesity is an issue that must be dealt with by all. For emerging health professionals in the field of food and nutrition, the debate on the true pathogenesis of obesity still exists with one side stating that genetics are to blame and that behind the high prevalence of obesity among racial-ethnic groups, there is a molecular component which pre-disposes these individuals to a lifelong struggle with weight.23 Public health research suggests that environmental factors are to blame. Research has shown that the few genes responsible for factors such as skin color cannot be linked to genetically complex diseases like diabetes mellitus.23 Therefore, the genetic characteristics of those populations with a high prevalence of obesity (African Americans, Hispanics, American Indians, Alaska Natives) does not offer an explanation about the significant health disparities between these groups and the European American, non-Hispanic population in the United States.23 While the more recent research supports those who argue an environmental pathogenesis, it is believed that these disparities are due to the complex interactions among genetic variations, environmental factors and individual health behaviors.23 The role of dietetics professionals is to lessen health disparities among these populations, whether their cause biological or environmental.

According to a survey done by Harris-Davis & Haughton,24 50.4 percent of the registered dietitians surveyed provided services to individuals who were from a different cultural background than themselves or from other racial and/or ethnic groups.24 This demonstrates the importance of cultural competence and awareness among dietetics professionals in order to make a significant impact on minorities’ health and life. While registered dietitians have the nutritional expertise to provide medical nutrition therapy to those with chronic diseases related to diet and lifestyle, the awareness and skills necessary to work with low-income and different racial/ethnic populations is a more difficult skill set to acquire. The principles of food justice education are based on the theory that the physical and social environments, policies and interventions regarding the food system must be changed in order to prevent the continuation of the obesity epidemic. In order to effectively implement food justice education as part of the school health curriculum, the registered dietitian must immerse himself or herself in a culture that often times is foreign to them. Particularly difficult is the issue of educating youth to advocate for justice when the registered dietitian themselves may never have dealt with food injustice and therefore cannot empathize with those who have dealt with the issue their entire lives.

Strategies to address the issues

Whether the obesity epidemic has an underlying biological or environmental determinant, the current state of those who are obese remains the same: those individuals struggling with the disease are under the impression that they have no control over the pathogenesis of their illness but yet they are held responsible for both the prevention of its onset and reversal. The social justice perspective identifies environmental factors as the cause of the obesity problem and the food justice movement offers a solution by emphasizing a comprehensive, coordinated intervention effort among health professionals and community members alike. According to Eric Braxton, executive director of the Funders’ Collaborative on Youth Organizing, youth organizing is a powerful but underutilized weapon in the fight against childhood obesity.22 Food justice education can be a powerful tool to not only address the environmental determinants of the obesity epidemic but also educate and inform those individuals in minority groups who suffer the most consequences from the obesity epidemic to gain control over a situation that was previously thought to be completely out of their hands. Food justice is a progressive movement that utilizes a strategy of empowerment among those most affected by socio-political injustices, which contribute to dietary intake disparities and the consequent childhood obesity epidemic. Since the war on childhood obesity began, registered dietitians and those health professionals who serve the minority communities most affected have fought tooth and nail to advocate for health-based policy change. While there have been many victories (improvement of national school lunch programs), there have been many hard-fought battles lost-but it has not been for a lack of trying. While the advocacy efforts of these health professionals are admirable, it can be assumed that those with the most motivation to change the system are the youth who live and deal with the struggle of maintaining a healthy weight without having a safe environment to get the recommended amount of physical activity and have significantly more difficulty obtaining low-cost, healthy foods.

The city of Chicago provides an excellent example of the detrimental impact of socio-economic and racial/ethnic disparities among overweight and obese adolescents. According to the Consortium to Lower Obesity in Chicago Children,25 “in some Chicago neighborhoods, primarily those with average household incomes lower than the citywide average and a majority of African American or Hispanic residents, closer to one half of the children are overweight or obese; and in some neighborhoods even more”. The Blueprint for Accelerating Progress in Childhood Obesity Prevention in Chicago: The Next Decade, published by CLOCC in 2012, proposes a social-ecological and multi-sectoral approach to obesity prevention. Most notable from this blueprint is the underlying premise that members of the community must be involved alongside the health professionals in the “development, implementation and evaluation of the interventions designed to address childhood obesity”.25 While there is no direct mention of the term “food justice education” in this blueprint, aspects of the food justice curriculum can be seen in objectives such as those guidelines which focus on school-based interventions and policy changes that impact the built environment. From a personal perspective, I have encountered the food justice curriculum provided by the Movement Strategy Center while working at a community center in Chicago that aims to serve underprivileged adolescents; this is a promising sign that the food justice movement is growing.

In light of the recent theories indicating the environment as root cause of disparities among minority populations with a high prevalence of obesity; a new movement to combat the obesity epidemic has begun to grow. The focus has shifted away from use of the medical model to change individual health behaviors and has instead been placed on a public health approach to address the accessibility to healthy food in the United States. To aid in this fight, a social justice perspective has been adopted by many health professionals and passed along to youth in affected communities in order to empower them to understand the injustice of socio-economic status and race/ethnicity as being the main determinants of access to healthy food. The food justice movement has a strong foundation of evidence-based research that illustrates the health disparities among low-income and minority populations and the hypocrisies of policies which control the production of food in the United States. Combined with these studies, evidence-based research that promotes the use of school-based interventions to prevent obesity in youth and the research that totes youth advocacy has proven to be a promising way to change the built environment. It can therefore be concluded that a school-based intervention that provides food justice education to youth in minority and low-income communities could prove to be a more sustainable approach to the obesity crisis.

To help spread awareness of this growing movement, registered dietitians, health professionals and community leaders must advocate for interventions that harness the power of youth to sustain permanent community changes which will reduce and prevent the incidence of obesity among children, increase access to healthy food and empower youth to advocate against environmental injustice. Community nutrition is a modern and comprehensive profession that includes, but is not limited to, public health nutrition, dietetics/nutrition education and medical nutrition therapy.23 For registered dietitians whose focus is health promotion and disease prevention, there is an increasing need to focus on community due to the knowledge that an individual’s behavior is highly influenced by the environment in which they live23 Providing youth today, particularly those affected by dietary intake and weight disparities, with the tools to become successful advocates for policies that promote the common good can lead to more sustainable, long-term changes being made. Together, we can build a society where equal access to healthy, affordable food is the norm rather than a privilege reserved for those who are most fortunate.

Dr. Joanne Kouba, Loyola University Chicago; Howard Area Community Center for providing an introduction to the concept of food justice education.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

©2015 Sommer, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.