Advances in

eISSN: 2378-3168

Literature Review Volume 12 Issue 2

Department of Health and Behavior Studies, Columbia University, USA

Correspondence: Ray Marks, Department of Health and Behavior Studies, Teachers College, Columbia University, Box 114, 525W, 120th Street, New York, NY 10027, United States

Received: March 09, 2022 | Published: March 28, 2022

Citation: Marks R. COVID-19 and childhood obesity. Adv Obes Weight Manag Control. 2022;12(2):45-50. DOI: 10.15406/aowmc.2022.12.00362

Childhood obesity, which is on the rise, is a risk factor for, as well as a possible negative outcome, of the restrictions enacted to protect against the novel corona virus 19 infectious disease [COVID-19]. To examine this premise the PUBMED and GOOGLE SCHOLAR data bases were sourced for relevant data published between January 2020 and March 2022 on the topic of COVID-19 and childhood obesity. These data bases show most current publications tend to portray a negative impact of COVID-19 lockdown policies on childhood obesity prevalence and outcomes. Many calls are hence being made for urgent efforts to mitigate a possible tsunami of chronic ill health and pain both in the short term, as well as in the long term among the millions of currently affected overweight children.

Keywords: childhood overweight, COVID-19, social isolation, school closures, obesity, pandemic, prevention

Childhood overweight or obesity, a current pervasive health challenge of immense proportions, affecting millions of children in all parts of the world, is a serious, often long lasting health condition that produces multiple adverse health outcomes and is often relatively impervious to interventions to reverse this state.1 Occurring when a child is well above the normal weight for his or her age and height, this growing epidemic has not only been poorly addressed in the past despite many and various attempts to mitigate this problem, but the presence of childhood obesity has apparently trended upwards as lockdowns associated with efforts to mitigate the infectious COVID-19 virus and its pandemic presence have unfolded.2

Indeed, not only are obese children at greater risk for acquiring severe COVID-19 disease,3 but as partly explained by Ribiero et al.,4 children as a group appear to have been negatively affected as far as weight control goes in the face of restrictive social distancing rules and multiple other forms of lockdown, whereby children’s daily routine including their active physical participation, a well established predictor of childhood obesity appears to have been adversely impacted, while increases in screen addiction have increased markedly during this time period among this vulnerable group.5,6 In turn, those children who have already acquired COVID-19 disease may tend to be fatigued and exercise less often,4,7 even though youth are generally less affected by this virus than adults.5

This situation, when viewed in both the short term and the long-term, is thus not only likely to prove highly deleterious in multiple ways, but likely to significantly impact the goal of attaining healthy aging for all in the United States and elsewhere in the future. It is also inconsistent with cost containment themes being stressed by policy makers and others. In particular, because excess weight in youth, commonly leads to one or more irreversible costly negative health outcomes in both youth as well as later life, it appears important to identify points of practice that might yet be harnessed to reduce this projected future health burden. Of specific concern is that efforts to mitigate the contagious COVID-19 variants may be impacted adversely and considerably, if the obesity issue remains unaddressed5,8 and youth continue to gain weight as a result of school closures.6

In this regard, while the key drivers of the obesity epidemic have been argued to stem largely from the persistent exposure of vulnerable youth and others to an obesity inducing (‘obesogenic’) environment,9 it is important to identify specifically what issues may currently be interacting even more excessively with known childhood obesity determinants to advance the rate as well as magnitude and prevalence of childhood obesity. As well, the impact of excess body weight on current infection risk, and its severity, as well as future comorbid illnesses and low life quality deserves heightened attention. Indeed, the observed systemic inflammation that is seen in cases of pediatric obesity might well foster other inflammatory conditions, such as those associated with COVID-1910 and obesity is the main pre existing condition raising the risk for COVID-19 in children.11

To this end, the current article focuses on the possible linkage of COVID-19 pandemic responses, such as social and mobility restrictions, plus school closures, as a relatively unexplored determinant of childhood obesity or its increased magnitude and severity. It examines if a case can be made for arguing against blanket social isolation rules in efforts to avert the risk of this infectious condition among youth and others, while basically paying little attention to its possible indirect adverse influences. Drawing on the available literature it outlines a potential pathway to consider in the future as regards preventing childhood and adolescent and adult obesity that is relatively unchartered.

Since the risk factors for childhood obesity of diet and physical activity are well studied, and the link between early obesity and cardiovascular diseases is well established, this overview specifically elected to examine whether the pandemic efforts to mitigate COVID-19 infections have had and will possibly continue to have negative interactions and wide spread adverse impacts.

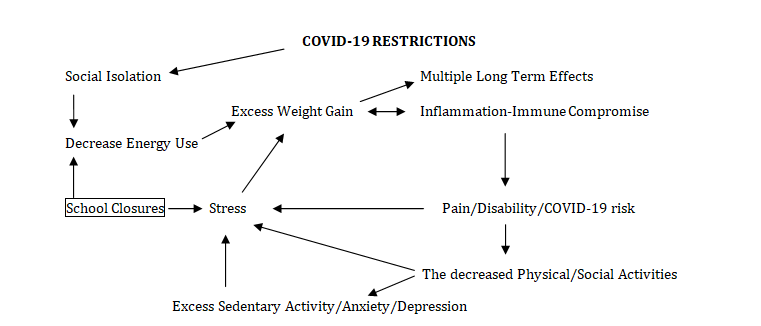

In particular, this report investigates the recent evidence base concerning the idea that excess social isolation can have an immensely negative impact in our view on physical activity, dietary choices, and messages that are aversive and emotionally charged and that can heighten obesity risk in young people if prolonged. Because overweight and obesity in childhood (including adolescence) are independently associated with serious physiological, psychological, and social consequences, including negative impacts on the musculoskeletal system, a major disabler of older persons, it examines if global efforts to mitigate COVID-19 can yield unanticipated weight consequences for young people as per Figure 1.

Figure 1 Hypothetical interaction of COVID-19 side-effects of social distancing, closures, and movement restriction rules and the risk of acquiring excess body weight and long term health challenges among vulnerable children.12–18

The review does not examine some of the other leading causes of childhood obesity, such as limited amount of safe space available for physical activities, a lack of healthy food sources in the area, and the abundance of fast-food chains. Using PUBMED and GOOGLE SCHOLAR data bases and key words: childhood/pediatric overweight or obesity and COVID-19, salient articles published as of January 1, 2020 up until March 10, 2022, were specially sought. Other issues were not examined directly. The term obesity was used to denote any degree of excess body weight that could prove injurious to a young person. The term COVID-19 is used to encompass all the variants of the novel corona virus 19. We did not focus on articles discussing childhood overweight published before 2020-with few exceptions. A paper by Noguiero-de-Almeida et al.,19 covering the years 2000-2020 is a good resource in this regard. Only a qualitative narrative overview is provided.

General findings

Among the various noteworthy findings in the current context, most published works clearly focus on the negative impact of COVID-19 on weight status in young people, and some possible solutions. A second perspective focuses on the nature of the risk posed by overweight as far as young people’s COVID-19 risk is concerned. As a whole, and between January 1 2020 and March 1 2022, PUBMED listed 282 articles, from multiple countries, implying this broad topic has been of considerable interest to many. Many are review articles or commentaries, and include observational rather than experimental studies and a fair proportion provide very stark titles depicting a possible future tsunami of childhood obesity and associated health problems consequent especially to the COVID-19 public health preventive imperatives.

Specific observations

Among the comments presently examined, Browne et al.,2 argue that the COVID-19 pandemic has severely disrupted children’s schedules, and exacerbated the impact of the obese inducing environment on both the risk for childhood overweight or for increasing its magnitude due to closures of health and schools services, disruptions of the child’s social activities, excess media usage, possible nutrition impacts, family stress, mental health challenges, and decreased opportunities to participate in physical activity.20 This in turn has not only increased the risk for excess weight gain, but has increased the risk for acquiring more severe COVID-19 disease as well as more severe complications among overweight youth.21

As well, the possible increase in use of nutrient dense foods, along with food insecurity, and excess stress, being left alone because parents have to work, plus heightened sedentary activities, screen time with greater exposure to fast food advertisements, a possible activity decline and less energy expenditure due to lack of outdoor time, outdoor sites for exercising safely, closures of school, and structured activities, plus a shift in sleep schedules with children going to bed and waking up later, and an increase in leisure-based screen time have been implicated in the realm of exacerbating specific obesity associated largely environmental determinants among youth during the pandemic period.1,16,22,23

Based on current observations, as well as past studies, Workman24 predicted overall increases in youth obesity risk and incidence due to pandemic associated school closures, although other factors, such as increased food insecurity, feeling more hungry than normal, irregular meals, excess stress, and sedentary lifestyle increases may well interact to accelerate weight gain in the face of multiple social restrictions and closures.25,26 A role for adverse childhood events due to school and work closures has also been cited as a possible unanticipated ‘obesogenic’ factor in the context of COVID-19 lockdown imperatives.27

These arguments are not purely academic given that research by Yang et al.,15 found Chinese youth appeared to not only gain weight during COVID-19 lockdowns, but their activity patterns also changed significantly, including less frequent active transport participation, moderate-/vigorous-intensity housework, leisure-time moderate-/vigorous-intensity physical activity, and leisure-time walking. Increases occurred in sedentary activities, sleep, and screen time. As well, Lange et al.,26 found children 2-19 increased their body mass at almost double the pre pandemic rate, with the highest rate of increase being demonstrated by children already overweight or obese and younger school aged children.

Consequently Zemrani et al.,5 as well as Patterson et al.,28 and others highlight the great importance of attending to this issue given its possible wide reaching physical, mental, social, self-esteem, and health consequences. As outlined by Patterson et al.,28 youth weight gain is also associated with time taken out of school, which could prove exceptionally harmful to the child, in multiple ways including, physically, mentally, socially, and academically.29 In one study, youth were found to increase their intake of potato chips, red meat, and sugary drinks during the lockdown period. At the same time, the duration of sporting activities decreased, while sleep and screen time increased,30 and most affected by weight gain were those children already deemed overweight or obese.31

In their review Nogueira-de-Almeida et al.,19 noted that obesity, a highly prevalent albeit possible preventable comorbidity is not only implicated in severe cases of childhood COVID-19, but this risk may be significantly heightened or accelerated in the face of any excess weight gain consequent to social isolation rules and mobility and health access restrictions. As outlined by Fang et al.,14 this set of isolation rules designed to avert a COVID-19 disease crisis, is yet a situation that may exacerbate the chances of acquiring or heightening associated deficits in lean mass, the intake of essential nutrients, along with increasing the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and their negative impact on the immune system. The dual illness of COVID-19 and excess weight in young people can also be expected to increase mortality risk as well as disease severity risk,32 making it harder for a surviving child to be active, while tending to increase sedentary practices, for example if the child’s breathing is compromised.

A study conducted in Korea by Kang et al.,33 over the pandemic period has thus shown this cycle of events can occur readily, rather than incrementally, and the degree to which childhood obesity was found to increase in the 6 month post pandemic period was said to depend the duration of school closures, including crèches and child development centers.23 This social distancing related unwanted negative impact in addition to the prevailing worldwide childhood obesity epidemic, is clearly serious since it may not only have the effect of increasing childhood obesity, but also childhood diabetes,34 poor social development, depression and poor mental health.35

As per Pietrobelli et al.,30 these multiple adverse emergent effects of the corona virus disease 19 pandemic lockdown containment strategies are likely to continue to impact the lives of many young people for years to come, especially those already struggling with weight control issues, even if lockdowns are lifted, if efforts to reduce excess periods of home confinement, sedentary lifestyles, and excess unhealthy eating practices are not curtailed.36 Although the long-term outcomes of childhood social isolation have not been studied, enough research currently points to an urgent need to foster all available amelioration strategies against childhood overweight, including limiting the impacts of social isolation and school closures. As well, more careful thought must surely be given as to how to address those persistent and future challenges that may persist or arise in this respect as the COVID-19 virus evolves so that no undue harm emerges-inadvertently. The overweight child should also be especially protected against depression,13 plus undue anxiety that is COVID-19 related in this regard,37 as it is the very young child that appears to be most vulnerable to the COVID-19 pandemic physical and social activity restrictions.38

Ortiz-Pinto et al.,8 who attempted to estimate the association between childhood obesity and the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection in a cohort followed from 4 to 12 years of age. using data from two independent sources: the Longitudinal Childhood Obesity Study (ELOIN) and the epidemiological surveillance system data from the Community of Madrid (Spain), for children 11-12 years of age, showed the accumulated incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection was 8.6% and childhood obesity was an independent risk factor for this.

Zemrani et al.,5 report the COVID-19 pandemic has greatly exacerbated key determinants of health, wherein children, although less directly affected by the virus than older adults, are paying a high price through the indirect effects of the crisis such as its effect on diet, mental and social health, screen usage, lack of schooling and health care, particularly among vulnerable groups. As such, preliminary data from the literature and a survey showed significant disruptions in nutrition and lifestyle habits of children post COVID-19, that could have life-long consequences for many children. As observed by An et al.,12 possible post pandemic declines in energy expenditure resulting from canceled physical education classes and reduced physical activity tended to increase childhood obesity prevalence by 0.640 points.

Woolford et al.,39 who compared body mass index of youths during the COVID-19 pandemic with the same measures made during the same period in 2019 found an increase in youth weight gain and overweight, especially among the youngest children. This latter finding was also recently noted by Dubnov-Raz et al.,38 Also attesting to the growing evidence base of adverse COVID-19 impacts on youth a study of a large pediatric primary care network by Jenssen et al.,40 found the already alarming disparities in obesity rates among children ages 2-17 increased following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, especially among young Hispanic children.21 Even possibly more serious is the finding that the efficacy of a standard-of-care pediatric weight-management intervention was substantially reduced during the COVID-19 pandemic, and that many children who received the intervention during the pandemic demonstrated significant weight gain despite receiving a 12-month weight-loss intervention.41 The unhealthy weight gain observed in young children over the pandemic period,42 tended to be most evident among already vulnerable children,43 and was significantly associated with school closure duration.44 At the same time, those children already deemed to be overweight or obese were observed to be exhibiting higher anxiety levels than desirable in the face of the significantly reduced lockdown associated physical activity opportunities, as well as exhibiting depression,13 and high levels of negative affect were observed to prevail during lockdowns in the face of excessive screen time, regardless of weight status.45

When considering the emergence of COVID-19, the sole focus on infection control via isolation mechanisms does not appear to have thoughtfully considered the possible immense and long-term untold harm on youth, especially in the realm of childhood obesity. Although clearly deemed salient and important in efforts to protect youth from being infected with the virus, especially obese youth who are found subject to more severe COVID-19 than non obese youth,3 these widespread home based and community wide lockdown and confinement restrictions imposed in a blanket manner for prolonged, uncertain, or alternating periods, without some due consideration, are beginning to reveal negative unintended impacts not only for those youth who are already considered obese, but for the non obese youth as well.43,46 This adverse unanticipated outcome of excess weight gain in an era when many efforts towards mitigating childhood obesity have been deemed essential, is thus not simply theoretical, and a topic to study in the future because even though studies in this regard remain limited, prevailing research reveals that there has been a significant increase in the risk of youth weight gain in the context of the multiple social isolation impacts of school closures, related food insecurity issues, stress, uncontrolled food intake, and decreased physical activity opportunities among school aged children,40,46,47 and this has occurred within a very narrow of time in many cases.48

Indeed, and according to Badesha et al.,49 and Chang et al.,46 there are strong indications that those public health rules introduced to curb the COVID-19 pandemic have already worsened the childhood overweight and obesity crisis globally, including negative changes in anthropometric measures of body mass index and body fat percentage.48 Key factors accounting for this undesirable trend include changes in dietary habits, such as more meals per day, and an increase in intake of sugary and fat saturated foods, plus the impact of restricted usage of public spaces and play areas and associated opportunities to engage in physical activities that were compounded by school closures.48 This gain in body fat mass and weight as a result of school closures alone is arguably due to a possible loss of the positive influence schools can have on key obesity risk factors, such as defined mealtimes, well planned meals, regular physical and sporting activities, less screen time and exposure to sugary drinks, and more regular sleep schedules. As compared with the pre pandemic period, children may also have become more reliant on family members to make dietary decisions, and who may themselves be weak and ill, unable to purchase or make healthy meals, may be poor role models, and unaware that excess social media usage as well as snacking may have an impact on possible youth weight gain.

As noted by Calcaterra et al.,50 the coexistence of childhood obesity and COVID-19 and changes in the bio-ecological environment have appeared to place youth at an increased risk for developing obesity and exacerbating the severity of this disorder. Cena et al.,51 agree with this argument and affirm children who are already considered obese have been shown to be at a higher risk of negative lifestyle changes and weight gain during the lockdown period. As well, obesity and COVID-19 can collectively affect the wellbeing of young people due to its negative effects on psychophysical health. As well as possible alterations in food choices, heightened snacking between meals, and more comfort eating, a marked decline in physical activity, alongside marked increases in sedentary activities can be expected to lead to an undesirable increase in a child’s weight status. In their study that took place in Greece, Androutsos et al.,52 found youth body weight increase during the pandemic was associated with an increased consumption of breakfast, salty snacks, and total snacks coupled with decreases in physical activity. At the same time, obesity, the most common comorbidity observed in cases with severe COVID-19 disease, suggests the presence of immune dysregulation, metabolic imbalances, along with inadequate activities and nutritional inputs may play a significant role in linking childhood obesity and COVID-19.

In sum, although children, as opposed to adults tend to have limited COVID-19 disease as a whole, and are low transmitters of the disease, and generally have higher rates of mild or asymptomatic disease, they have still been subjected to the same local, regional, and national public health rules designed to prevent the widespread infectious and highly contagious COVID-19 virus.53 The presence of childhood obesity does however, tend to raise the COVID-19 risk among this group, regardless of lockdowns, while those children who are subject to school closures and stay at home rules are found to be especially susceptible at higher rates than one would predict to acquiring excess weight than in pre pandemic times and hence to a possible risk of multiple comorbid health conditions.9 In this regard, the COVID-19 pandemic response of school closures has clearly raised childhood obesity susceptibility in all parts of the world, and with this, numerous probable adverse short and long-term unintended health and social consequences.43 In particular, the mental health consequences of childhood obesity, plus possible excess bullying by others, and further isolation due to respiratory challenges and a compromised immune system that has not been readily studied, will predictably unfold over time. Unfortunately, it is those youth who are already marginalized and who often suffer from food insecurity22 that appear to be highly vulnerable in the face of prolonged closures of preventive health services, schools, and youth obesity education and sporting programs.54 This observed increase in childhood weight status is not just a growth related observation, as discussed by Beck et al.55 This group who studied children in a relatively disadvantaged location in the United States found the children’s mean monthly change in body mass z-score of 0.02 to be equivalent to a yearly increase in the same measure of 0.24. As observed, this weight gain among children in San Francisco with overweight and obesity during the COVID-19 pandemic far exceeded healthy weight gain for this age group.

Hence, while this overview is not without limitations and did not explore the quality of the prevailing data, and much remains to be learned, it appears that caution will need to be adopted in the future if and when movement restrictions appear imperative. Indeed the possible societal losses as well as multiple impacts on the lives of vulnerable children and their families will resonate for years to come as the unanticipated lockdown consequences unfold. To avert excess and preventable consequences of childhood weight acceleration presently observed-and other consequences not yet studied or apparent, three areas of influence appear to have been put forth, education, policy, and economic imperatives as summarized below:

In terms of policy, several approaches have been put forth as follows

First, the global involvement of all stakeholders, including governments, schools, and families, to maximize efforts towards reducing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on childhood obesity is strongly encouraged.27,58

As well, support for regular body mass screenings, food security for all, increased access to evidence-based pediatric weight management programs and food assistance resources, plus state, community, and school resources to facilitate healthy eating, physical activity, and chronic disease prevention are deemed highly desirable.26,42

In addition, more effective worldwide policies, guidelines and precautionary measures28,29,57,59 that support the design and implementation of comprehensive public health strategies to preserve children´s physical, social, and mental health status during/after the pandemic, particularly among children with social vulnerabilities25,29,36,60 as well as those with youth with pre existing obesity, children who have suffered COVID-19 infections, children with comorbid health conditions, and children who lack insurance or are socio-economically deprived are indicated.13,43,56

At the same time, specific support for families who have struggled to manage their child’s weight during this pandemic period may be needed in order to have them continue to engage in structured weight management approaches as society renormalizes.40

In terms of active programming, various recommendations focus on encouraging

Public health programs that can involve policy makers, plus the whole family and community, and that work within the school to foster healthy lifestyle attributes, plus efforts to help children maintain and participate in adequate levels of physical activity, while limiting leisure screen time may be particularly relevant for all children, especially those who are overweight/obese.29,42,45,48

In addition, culturally and linguistically appropriate parental education, focused efforts to address food insecurity issues early on, keeping schools, community, and childhood centers open, building a strong economy, restoring youths’ emotional health and equilibrium, and providing incentives for physical activity participation and positive social experiences appear warranted in the months ahead.44,61,62 Lessard et al.,63 urge health providers to be specifically aware of the potential for excess youth exposure to and experiences of weight stigma as observed during the pandemic, and encourage more supportive family approaches and school based engagement on support, rather than stigmatizing weight related communications in the future.

In the interim, as per Rajmil et al.,64 we strongly urge governments to take these multiple costly possibly irreversible negative public health consequences for many youth that emanate directly from multiple lockdown attributes seriously as we go forward. Moreover, we urge them to take them into account in the future and to advance very cautiously before issuing and mandating the universal adoption of multiple restrictive or precautionary measures that can predictably affect millions of low risk children adversely and directly, and possibly for the rest of their lives.

As per Hauerslev et al.,65 childhood obesity has been markedly exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, largely owing to arbitrary decisions made by numerous leaders at different levels, without due thought of possible unintended consequences for youth. These include closures of many important life affirming services and venues, alongside more screen time, wherein it has been shown that a number of commodity industries have adapted and increased their marketing efforts during the pandemic, and some have partnered with fast food or chocolate companies to provide special versions of popular online games. “COVID-washing” of unhealthy products, whereby brands align with an empathetic response to the pandemic to enhance their own image, has, in some instances, also clearly influenced children’s and parent’s food choices, regardless of the law, according to these authors, and thereby the risk of childhood obesity and damaged child health. To reverse these emergent adverse health determinants and others, the authors urge global leaders to look towards multiple mitigation policies and to leave no stone unturned in efforts to regain lost ground in the fight against childhood obesity, especially as far as marginalized youth who live in poverty and whose parents may have lost their jobs and health insurance are concerned. This includes access to healthy school meals, and physical activity and lowering availability of unhealthy foods during any future pandemic.

Although not exhaustive, a review of current literature clearly shows that the implementation of highly restrictive movement rules and lockdowns in response to COVID-19 infection risk has had immediate consequences for young people, among others in the context of weight control that are likely to compound as time proceeds due to its impact on youth weight gain alone. It is further concluded that even though prior and ample research has clearly shown physical activity and poor eating to account for the worldwide childhood obesity epidemic this did not appear to be factored into the pervasive and prolonged public health laws to limit movement and close schools in any part of the globe. This reveals a clear case where the evidence base did not appear to drive the highly restrictive lockdown public health practices in all respects, and where fear was embraced regardless of its overall impact of the means of averting this where possible. As such, it is concluded that immense efforts must now be made to provide all means of attenuating the possible fallout of the generic lockdown and its impact on accelerating youth weight gain among children wherever they live.

None.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

None.

©2022 Marks. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.