Advances in

eISSN: 2378-3168

Research Article Volume 6 Issue 3

Department of Health and Nutrition Sciences, Montclair State University, USA

Correspondence: Jelena Skopinceva, Department of Health and Nutrition Sciences, Montclair State University, USA

Received: November 27, 2016 | Published: March 20, 2017

Citation: Skopinceva J. Assessing the nutrition related knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of fitness professionals. Adv Obes Weight Manag Control. 2017;6(3):107-111. DOI: 10.15406/aowmc.2017.06.00160

Today we live in the world where everyone is a nutrition expert. All you have to do is click on Google, pick a magazine or ask anyone who is somehow related to fitness. There are thousands of health clubs, gyms and group-exercise facilities out there. Most people, working in the fitness industry, are giving out nutrition advice to their clients. This happens because of one simple reason; people believe in their trainers and ask their instructors for advice. Their instructors are usually in great shape, have a ton of energy and are expected to know the answer to every question. The purpose of this study is to use a quantitative approach (online survey) to assess the nutrition-related knowledge, attitudes and beliefs of fitness professionals. Our goal is to understand whether fitness professionals are able to provide reliable nutrition information to their clients. The findings help us to determine the extent and type of education needed to help fitness professionals expand their knowledge in nutrition. “Assessing the nutrition-related knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of fitness professionals” research is helping to evaluate the need of nutrition education in the fitness field. A very limited amount of studies have been done on this topic. Further research may be needed to improve the reliability of this study. Research questions that need to be answered are: “Do fitness professionals have any knowledge about nutrition? Are they providing nutrition advice to their clients? Evaluation of the knowledge and beliefs of fitness professionals with the survey tool helps to establish whether their knowledge is not contradicting the information that is provided by nutrition professionals.

Proper nutrition is crucial when it comes to weight loss, athletic performance, and any physical activity. Three major organizations, such as American Dietetic Association, Dietitians of Canada, and the American College of Sports Medicine announced, “Physical activity, athletic performance, and recovery from exercise are enhanced by optimal nutrition” (2009). A combination of physical activity and nutrition treatment gives a better health outcome than just physical activity alone. A keystone in physical activity, especially when it comes to vigorous physical activity, is through modification of diet.1 Previous research has shown that to maintain steady body weight, while increasing physical activity levels, energy requirement is necessary for maintaining good health.2

While obesity numbers are rising in the United States, so are the numbers of fitness professionals.3 The employment or numbers of fitness trainers and instructors in 2012 was 267,000, as the Bureau of Labor Statistics states. This is the base year of the 2012-22 employment projections; this number should increase by 13% by the year of 2022, which is slightly higher than average growth.4 This number does not seem to include self-employed fitness professionals. Also, it is not clear if this data covers all the instructors or just personal trainers. There are many more specific qualified fitness professionals, such as group instructors, yoga teachers, TRX trainers and more.

Over the past several decades the personal training industry has grown extensively. In fact, fitness professionals are often considered to be the "gatekeepers" when it comes to dispensing information as related to exercise and nutrition. While most fitness and nutrition professionals agree a combination of physical activity and sound eating are important for improving body composition and athletic performance, there appears to be confusion regarding how much nutritional education, counseling, or advice fitness professionals can legally and ethically provide to their clients/athletes.5

Furthermore, a major concern for professionals lacking sports nutrition knowledge is that they might disseminate incorrect information formulated on theory or unsupported by research. There is a very limited amount of studies done on nutrition education for fitness professionals. However, there is research done by NATA (National Athletic Trainers’ Association), which explains that athletic trainers, who have obtained a bachelor degree in exercise science, are lacking the knowledge about nutrition. Therefore, the athletes that they are training have inadequate knowledge as well. NATA is suggesting that nutrition education programs are needed for athletic trainers and qualified nutrition educators should instruct these educational programs.6

In addition, there are thousands of fitness professionals who have earned only high school diplomas and some specific fitness certification. Therefore, they simply may not have enough educational background to differentiate between reliable nutrition information and diet trends. Nutrition content was present in 91% of the curriculums. Three curriculums scored weak ratings, three moderate ratings, and five strong ratings. Weight management content was present in 91% of the curriculums but none matched AND’s (Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics) recommendation for weight loss.7 The extent to which personal trainers (PTs) regularly engage in the unlicensed practice of nutrition counseling has not been documented. Approximately 91.5% of PTs spend time on nutrition counseling with clients, and 42.6% include nutrition counseling as part of their fees for services. Approximately 60% of PTs demonstrated inaccurate information on protein requirements, and 48.1% incorrectly believed dehydration begins to occur when an athlete experiences a total water deficit of more than 10% of body mass. One out of 129 personal trainers had a nutrition college degree, however, 82.2% described themselves as “somewhat” or “definitely very prepared” to teach clients about nutrition.8,9

This study hypothesis is: if fitness professionals provide nutritional advice to their clients, then we must provide them with the relevant nutrition education. Fitness professionals are pursuing their nutrition education through mostly unreliable sources, continuing to disseminate anecdotal information. So the questions we have to ask, are: Do fitness professionals have any knowledge about nutrition? Are they providing nutrition advice to their clients? Physical therapists, exercise scientists and athletic coaches don’t seem to be intimidated by the fitness trainers. The American College of Sports Medicine provides certification for personal trainers and group instructors. Nutritionists could provide education as well. Nutritionists need to gain their authority back instead of competing in the field where they are the experts. It’s them that fitness professionals should look up to and ask their questions.

Participants

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the knowledge of fitness professionals, including any instructor who is providing exercise training, including any specific fitness field, and in all type of training. A simple random sample of fitness professionals (n = 50), females (n = 21), and males (n = 29) of all ages were recruited via social media websites. Many different types of fitness professionals are included; specifically, personal trainers (n = 8), group instructors (n = 3), yoga teachers (n = 3), chiropractors (also sports conditioning trainer) (n = 1), strength training and conditioning (n = 8), fitness management (still providing fitness conditioning) (n = 2), Pilates (n = 2), specific rehab (n = 2), medical exercise specialist (n = 1), kettlebells coach (n = 1), running coach (n = 1), exercise specialist (n = 1), obstacle racing and endurance trainer (n = 1), exercise physiologist (n = 1), health specialist (ACSM) (n = 1), functional training instructor (n = 1), sports performance training coach (n = 3), dance instructor (n = 1), post- and pre-rehab trainer (n = 1), indoor training specialist (n = 1), balance training instructor (n = 1), corrective exercise trainer (n = 2), swim coach (n = 2), TRX training (n = 1), not specified field in training (n = 4). Participants who skipped the question, on the state of residence, are sorted out, since many people on social media could be living outside of the United States. Participants who skipped and didn’t answer 2 or more questions are eliminated as well. Most fitness professionals provided more than one distinct type of training. Fitness professionals are identified by the specifics of their training field. The goal of this study is to include as many different types of fitness professionals as possible. Every participant completed a consent form online, and had a choice to decline participation in this study. The Montclair State University Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Instruments

The survey for fitness professionals was carefully designed to help evaluate the knowledge they already have. Their beliefs and attitudes, whether they are confident in their knowledge, were estimated as well. Survey questions evaluated the confidence and attitude of fitness professionals toward learning more about nutrition. The rest of the questions were on frequency of providing nutrition advice, which provided us with a bottom line, on how important it is, for coaches to obtain valuable nutrition information. All the data was calculated and provided in numbers, to establish whether they are significant statistically or not. Tables and graphs are arranged to show the results and investigate results and casual relationships. Self-administrated survey, which consisted of nutrition knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and demographics sections, was developed and all the data was gathered on Survey Monkey. Participants answered demographic questions about their age, sex, ethnicity, level of education, years of experience in fitness field, sources of their nutrition knowledge, and state of residence, marital status and household income. Questions about nutrition knowledge often were asked twice, in a different form, to access a nutrition background of the participants. To evaluate the knowledge of fitness professionals, questions were asked about macronutrients, micronutrients, hydration, weight loss and exercise, as well as a question about the urgency of nutrition education for the instructors provided. Questions, on beliefs and attitudes, asked to clarify the sources of the information, from which instructors are learning. Nutrition Survey for Fitness Professionals consisted of 44 multiple-choice questions. A four-point Likert scale (1 = don’t know, 2 = disagree, 3 = agree, 4 = strongly agree) to rank questions about nutrition knowledge, and four-point Likert scale (1 = never, 2 = sometimes, 3 = usually, 4 = always) was used for attitude and beliefs questions. Fitness professionals were also asked to answer “yes” or “no” on a few questions such as “Government sources, such as the USDA and the FDA, are reliable sources of nutrition information. A flyer was made to get the attention on social media, accommodated with the blurb explaining research standpoint, and distributed via social media such as Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and LinkedIn, which had a link leading to survey on Survey Monkey website. Fifty (50) participants were selected conveniently from 95 survey responders. Sample was extracted randomly via simple random sampling, with an equal chance of being selected for everyone. Completing the survey took around 6-14 minutes, instead of anticipated 20-30 minutes. Knowledge of the participants was evaluated against their confidence in their answers. Quantitative research design was used for this research, using SPSS software for statistical analysis. Surveys were viewed as prime examples of quantitative research and later evaluated against the strength and weaknesses of statistical, quantitative research methods.

Procedures

Fitness professionals were contacted via social media and all 50 participants were randomly selected through simple random selection out of 105 responders. A link through secure website Survey Monkey was provided and every participant was assigned an identification number, without providing any personal information that could compromise their privacy. None of the participants were required to provide their e-mail address. A link, given to the participants, provided more in depth information about the study, in the consent form followed by the questionnaire. Responses via Survey Monkey were tracked via unique identification number provided to every participant. Some of the participants have contacted principal investigator and were encouraged with follow up message to participate in the study. Data was collected within one month, approximately. No follow up e-mail was send to the participants, since no e-mail address was provided on Survey Monkey website.

Data analysis

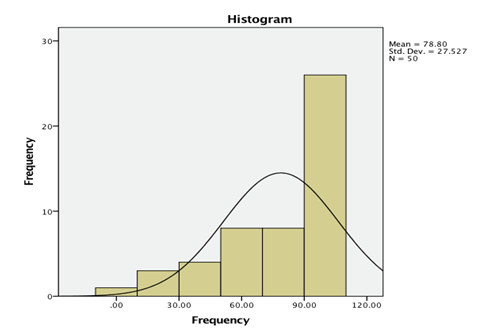

To evaluate knowledge, education, frequency and confidence, descriptive tables are provided. Frequency distribution and percentile ranks are shown in the tables for the specified variables, such as knowledge and confidence (Table 1 & Figure 1). Crosstabs were used in the descriptive statistics to compare means, such as knowledge and education, or knowledge and confidence (Table 2).

Another three histograms showed how informed trainers are about nutrition knowledge, reliability of the sources providing nutrition knowledge, and frequency of nutrition professionals of referring their clients to a registered dietitian. Pearson’s Correlation 2-tailed test was performed to determine the strength of the linear relationship between variables, such as knowledge, frequency and confidence, or informed, reliability and sources (Tables 3 & 4).

N |

Minimum |

Maximum |

Mean |

Std. Deviation |

|

Knowledge |

50 |

53.00 |

100.00 |

81.1600 |

12.48241 |

Education |

50 |

1.00 |

6.00 |

4.4000 |

1.42857 |

Frequency |

50 |

.00 |

100.00 |

78.8000 |

27.52661 |

Confidence |

50 |

17.00 |

100.00 |

69.9000 |

23.71794 |

Table 1 Frequency distribution provided for mean and standard deviation, tables* in results

Figure 1 Histograms are showing the distribution knowledge, frequency of providing nutrition advice, confidence in giving the right advice.

|

Knowledge |

Frequency |

Confidence |

|

Knowledge |

Pearson Correlation |

1 |

.159 |

.067 |

Sig. (2-tailed) |

.271 |

.644 |

||

N |

50 |

50 |

50 |

|

Frequency |

Pearson Correlation |

.159 |

1 |

.367 |

Sig. (2-tailed) |

.271 |

.009 |

||

N |

50 |

50 |

50 |

|

Confidence |

Pearson Correlation |

.067 |

.367 |

1 |

Sig. (2-tailed) |

.644 |

.009 |

||

N |

50 |

50 |

50 |

Table 2 Spearman Correlation Coefficient test was done to double-check Pearson’s correlation test*

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-talied)

N |

Minimum |

Maximum |

Mean |

Std. Deviation |

|

Sex |

50 |

1.00 |

2.00 |

1.4200 |

.49857 |

Age |

50 |

1.00 |

5.00 |

2.7000 |

1.09265 |

Education |

50 |

1.00 |

6.00 |

4.4000 |

1.42857 |

Valid N(listwise) |

50 |

Table 3 Frequency distribution tables, tables* are providing the percentile ranks for experience in years, knowledge versus confidence in percentage.

N |

Minimum |

Maximum |

Mean |

Std. Deviation |

|

Informed |

50 |

1.00 |

2.00 |

1.2800 |

.45356 |

Reliability |

50 |

1.00 |

2.00 |

1.5200 |

.50467 |

Valid N(listwise) |

50 |

||||

Reference |

50 |

1.00 |

4.00 |

2.7000 |

1.09265 |

Valid N(listwise) |

50 |

Table 4 Crosstabs did not show a correlation between knowledge and confidence*

Results pertaining to knowledge education, frequency and confidence, in descriptive tables* are mean and standard deviation for each variable in separate table, including first table with descriptive statistics of sex, age and education level of the participants. Percentage used to describe these variables, with mean on knowledge 81% of participants. Mean on education level of the participants is showing that most fitness professionals haven’t obtained a college degree and their knowledge is coming from some specific certification, whether it’s a personal trainer’s certification, or some other nutrition certification. Frequency of providing nutrition advice, for fitness professionals is 79%, and confidence on giving an appropriate advice is 70% in general.

Pearson’s Correlation 2-tailed test showed weak correlation between knowledge, frequency and confidence. The correlation between keeping informed, reliability and sources of information did not show a correlation. Spearman Correlation Coefficient test did not show a correlation between variables (Figure 2).

Nutrition knowledge

Quantitative method, used for this research, emphasized objective measurements, such as knowledge, attitudes and beliefs of fitness professionals, using statistical, mathematical and numerical analysis of data collected through survey. The focus was on gathering numerical data to generalize and explain the result of this particular survey. A descriptive, quantitative research design is used, where provided survey measured subjects only once. As survey has shown, nutrition knowledge of fitness professionals, in total, is above average. Mean for nutrition knowledge is 81%, with maximum 100% and minimum of 53%. Most of the fitness professionals, who had knowledge above average, have received a college 4-year degree or higher, in the past. The majority of instructors have received their education about nutrition from a certified, nutrition or personal training course. Even without having an appropriate training on nutrition education, as many as 79% of fitness professionals provide a nutrition advice to their clients, Plus 70% of all the trainers, participating in this study, are confident in their advice to be appropriate.

Sources of nutrition knowledge

Many fitness professionals do not believe that government is providing an appropriate nutrition education, especially to fitness professionals. This number is as high as 60%, in this particular study. When it comes to the adequate nutrition education, 79% of participants said there isn’t enough nutrition education. Instructors are often misinformed, and they’re exposed to nutrition information from the multiple sources. As many as 76% of the participants are saying that they’re trying to keep themselves up to date on all the latest research findings in nutrition. Journal article reading is popular within 55% of participating trainers in the survey, but only 1% of the participants will turn to the government website for needed information. Any website is used, to read about nutrition, by 34% of all participating instructors.

Reference to registered dietitian

Registered dietitian who is specializing in sports nutrition is a critical affiliate to any fitness facility. Unfortunately it isn’t always the case within fitness world. The RDs, who could provide medical nutrition therapy, comprehensive nutrition assessment on sports nutrition, and identify nutrition problems, which are affecting health and performance, absent for the most part at the gyms. Therefore, fitness professionals are taking the responsibility for nutrition education of their clients. Only 14% of the fitness professionals, participating in the study, said that they always referring their clients to a registered dietitian. Another 19% refer them usually, and 21.5% will never make the reference to a registered dietitian. Rest 45% said that they will do it sometimes.

One limitation of this study was that survey questions were answered online; it raised the question, how many people looked up and goggled the right answer. The survey was anonymous and that didn’t give any guarantees for the answers given in this study. Another limitation may be that participants didn’t actually read the question, before answering it. They browsed through the questions and made an educated guess.

Since members at the fitness facilities often reach out to the fitness professionals for a nutrition advice, nutrition knowledge among instructors is critical. Although, fitness professional have demonstrated adequate nutrition knowledge, some of them were overly confident in their answers. Trainers who had more knowledge and education were less confident, while less educated trainers who showed less knowledge, appeared to have more confidence in their answers. Personal training certification holders showed the most confidence in their knowledge, compared to coaches who have received their high school diploma, bachelor degree or higher education. Frequency on giving nutritional advice was more prominent in participants with 4-year college degree, even when they had non-nutrition degree. Beliefs and attitudes of the instructors are not statistically significant. Majority of participants give their clients a nutritional advice. Often trainers answered the question believing that they know the right answer but couldn’t follow up with the right answer in a following question. Some participants, while answering the questions, claimed that they not supposed to give a nutritional advice, while the survey showed that they’re discussing nutrition with their clients anyway. Appropriate nutrition knowledge, of fitness professionals, could improve standard of care and increase the number of references to the registered dietitian, when necessary, thus everyone is on the same mission to fight obesity.

None.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

©2017 Skopinceva. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.