Advances in

eISSN: 2378-3168

The current perception is that initial successful weight loss is often followed by weight regain after 5 y of the dietary intervention.1 Evidence from systematic reviews suggests that long term weight loss through changes in eating and physical activity is possible,2 but although formal behaviour change interventions and self-guided efforts at individual behaviour change are successful in inducing weight loss, few people manage to maintain these changes in weight over the long term.3 Clinical dietitians and nutritionists face multiple barriers to effectively delivering lifestyle interventions in today’s health care setting. They are not trained to keep people accountable for their new, healthy choices, their new physical image and how to change their eating habits. They are not trained to recognize eating patterns and generate new, healthier behaviors but, nonetheless, remain powerful motivators in helping patients initiate and maintain weight loss efforts that reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes and other chronic diseases. A coaching intervention focused on patients’ values and sense of purpose may provide added benefit to traditional wellness, diabetes and weight loss education programs.2 Fundamentals of health coaching may be applied by nutritionists to improve patient self-efficacy, accountability, and clinical outcomes.

Keywords: weight loss, diet coaching, health coaching, obesity, nutrition, NLP, mBIT

mBIT, multiple brain integration techniques; NLP, neuro-linguistic- programming

This conceptual paper is about the insufficient training of Dietitians and Nutritionists as Health Providers who promote Wellness and Wellbeing. Evidence from systematic reviews suggests that long term weight loss through changes in eating and physical activity is possible,2 but although formal behaviour change interventions and self-guided efforts at individual behaviour change are successful in inducing weight loss, few people manage to maintain these changes in weight over the long term.3

First of all, I will clarify the definition of a Dietitian. According to the WHO,4 “dietitians and nutritionists assess, plan and implement programs to enhance the impact of food and nutrition on human health. They may conduct research, assessments and education to improve nutritional levels among individuals and communities”. Furthermore, the International Confederation of Dietetic Association’s5 sets the definition of a dietitian as “a person with a qualification in nutrition and dietetics, recognized by national authority. The dietitian applies the science of nutrition to the feeding and education of groups of people and individuals in health and disease”.

A dietitian is a degree-qualified health professional who helps to promote nutritional well-being, treat disease and prevents nutrition related problems, provides practical, safe advice, based on current scientific evidence and holds a graduate qualification in nutrition and dietetics in the UK, according to the British Dietetics Association.

Dietitians translate nutrition science into understandable, practical information about food, allowing people to make appropriate lifestyle and food choices. They treat a range of medical conditions with dietary therapy, specially tailored to each individual and give advice on healthy eating for all ages, races, cultures and social groups. Dietitians conduct research relating to health, diet and nutrition, advice industry and government, give talks and lectures to health professionals and the public and, sometimes, teach in higher education.

Obesity is a disease and a complex health issue6 and should be treated like that, according to American Heart Association. Obesity results from a combination of causes and contributing factors, including individual factors such as behaviour and genetics. The behavioural factors include dietary patterns, physical activity, inactivity, medical use and other exposures. Additional contributing factors in our society include the food and physical environment, educational skills and food marketing promotion.7

Obesity related conditions are heart diseases, metabolic syndrome, hypertension, stroke, type 2 diabetes and certain types of cancer, which are the leading causes of preventable death. More than 1/3 of US adults are obese.8 The obesity and diabetes trends in US are presented in Figures 1 & 2.

In Europe, obesity prevalence has doubled between 1980 and 2008. In 2008, more than 50% of both men and women were overweight, 23% of women and 20% of men were obese. Greece is in third position in Europe (Figure 3).

As far as children’s obesity is concerned, the picture speaks for itself (Figure 4). Over 60% of children, who are overweight before puberty, will be overweight in early adulthood.9

Children’s obesity is strongly associated with cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, orthopedic problems, mental disorders, underachievement in school and lower self- esteem.

So far, less than 20% of the dieters are able to achieve and maintain a 10% reduction over a year,10 more than 1/3 of lost weight return within the 1st year11 and the majority have regained the lost weight within 3 - 5years.12

According to the literature, successful obesity treatment has very specific weight loss interventions. To define the “successful treatment” is an intervention that created ≥5% weight loss from baseline and a maintenance phase during which the ≥5% weight loss was maintained from baseline to 12months.13 The intervention include an energy deficit, commonly achieved by reduced fat intake, increased dietary fiber (21% of successful interventions), physical activity (88% of successful interventions) and behaviour training (i.e. self-monitoring) (92% of successful interventions).

Some habitual behavioural strategies, such as monitoring weight, setting goals and adjust them, if necessary, tracking food and calorie intake and creating a supportive environment at home and work that discourages overeating, are essential elements of the behaviour training. According to American Heart Association, people are more likely to follow a weight-loss routine when guided by a registered dietitian, behavioural psychologist and other trained professional in the health care setting (such as a wellness or a health coach), based on the AHA guidelines.

Furthermore, there are some recent studies showing the effectiveness of low carbohydrate diets in metabolic syndrome, blood pressure and lipids.14 A meta-analysis of randomized trials of low-carbohydrate dietary interventions conducted by Nordmann et al.,15 found that low-carbohydrate diets produced significantly greater weight loss after 6months than did low-fat diets, although the differences were not statistically significant at 1 year. In a trial-level meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing LoCHO diets with LoFAT diets in strictly adherent populations that was conducted by Jonathan Sackner-Bernstein et al.16 demonstrates that each diet was associated with significant weight loss and reduction in predicted risk of ASCVD events. However, LoCHO diet was associated with modest but significantly greater improvements in weight loss and predicted ASCVD risk in studies from 8 weeks to 24months in duration. These results suggest that future evaluations of dietary guidelines should consider low carbohydrate diets as effective and safe intervention for weight management in the overweight and obese, although long-term effects require further investigation.

Elfhag et al.,17 in their review of factors associated with weight loss maintenance and weight regain, pointed out some characteristics and successful strategies, such as that people with more initial weight loss could maintain this loss a longer time, they had self-determined goal weight, they had physically active lifestyle, regular meal rhythm (breakfast and healthier eating), a control of over-eating and they were self-monitoring of eating behaviors.

Furthermore, they reported in more detail character traits and behaviors like internal motivation to lose weight, they had social support, better coping strategies and ability to handle life stress, self-efficacy, and autonomy, assuming responsibility in life and overall more psychological strength and stability.

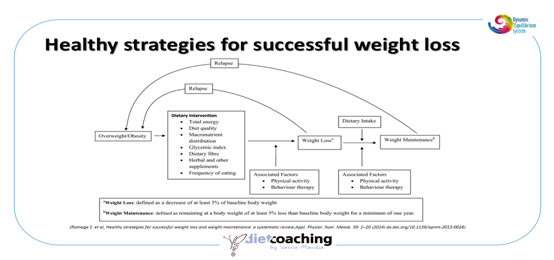

Figure 5 presents a diagram that shows the healthy strategies of successful weight loss and maintenance, by Ramage et al.,13 I want to underline the fact that lapses and relapses can happen while in the weight loss or/and the weight maintenance phase, that may lead to the initial weight gain. Dietitians should be prepared and prepare their clients as well, about these lapses or even conduct a controlled lapse in a coaching session, if they are trained on how to do that.

Dietitians should help their clients to reframe the lapse as a temporary setback and in general, assistant in reframing mistakes as learning opportunities, rather than failures. In weight maintenance phase, when lapses are happening, people may need assistance in order to set new goals and get refocused. Lapses are external abandonments of the new behaviors and may lead to the reductions or even the disappearance of the benefits of them.

When we look at behavioural lifestyle change, the challenges of habit, peer health group norms and cognitive structures kick in, like the American Psychologist Abraham Maslow has addressed (Figure 6). But our suffering and challenges serve to bring out greater strengths than we have imagined.

The most recent Dietary Guidelines for Americans (2015-2020)18 by the USDA provides guidance for choosing a healthy diet and focuses on preventing the diet-related chronic diseases. Its recommendations are ultimately intended to help individuals improve and maintain overall health and reduce the risk of chronic disease. It’s the first time that its focus is disease prevention, not treatment. This edition also includes data describing the significant differences between Americans’ current consumption and the Dietary Guidelines recommendations. It also recommends where shifts are encouraged to help people achieve healthy eating patterns. They claim that “these analyses will assist professionals and policymakers as they use the Dietary Guidelines to help Americans adopt healthier eating patterns and make healthy choices in their daily lives, while enjoying food and celebrating cultural and personal traditions through food. Now more than ever, we recognize the importance of focusing not on individual nutrients or foods in isolation, but on everything we eat and drink-healthy eating patterns as a whole-to bring about lasting improvements in individual and population health.”

There are many definitions about Wellness, but the most admissible is of J. Allen “a process of becoming aware of and making choices toward a more successful existence”. In his Illness- Wellness Continuum, John Travis19 positions the field of wellness with an eventual goal of self- actualization. In his “Wellness Workbook” he states that “it doesn’t matter where you are now at the continuum, but rather the direction in which you are facing”. Michael Arloski20 in his book “Wellness Coaching for Lasting Lifestyle Change”, brings Maslow’s terms into wellness terms, helping wellness coaches to align their coaches with their needs while dieting. Travis in his 12 Dimensions of Wellness uses the word “eating” instead of the trigger words “dieting” or “nutrition”. Using the appropriate linguistics can have a great impact on our subconscious minds. Eating, as a wellness dimension, is not only about what we eat, but also about when, where and even why we eat, it’s about what a person digest (both literally and metaphorically) and what they bring in their inner world.

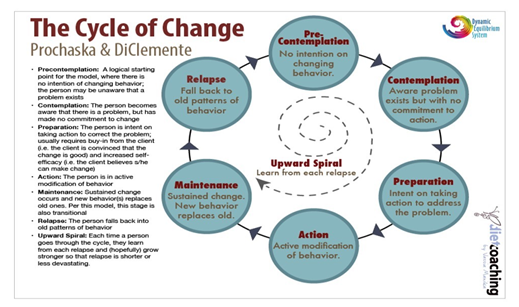

Research has shown that self- change is a staged process.21 We move from not thinking about changing behaviour to thinking about it, to planning to change, and to testing out ways to do it before we actually start. Using inappropriate techniques that prematurely encourage new behaviors can discourage change. For example, people who have not yet made up their minds to change are not sufficiently ready to adopt behavioural strategies. Applying this kind of pressure can cause them to withdraw from the change process. To avoid such an outcome, it is important to identify the stage of change that clients may be in when they first come to the Dietitian’s office (Figure 7).

This is not a part of the educational and scientific training of a Dietitian.

The combination of wellness coaching and some evidence- based behavioural, existential, mind-and-body techniques, such as CBT, mBIT, NLP, along with the solid scientific background and training of a registered dietitian is a perfect match. Dietitians trained as wellness coaches with extra skills and techniques are more likely to increase their emotional intelligence, increase empathy and other communication skills, make concrete coaching relationships with their coaches22/clients built on trust, openness, warmth, exploration and respect of their subjective experience of their world and help them make sustainable lifestyle changes. One of the most important aspects of that are mindful eating,15 sensing and enjoying the “Good Life” (eudaimonia), according to Aristotle, who also stated that “Excellence is an art won by training and habituation. We do not act rightly because we have virtue or excellence, but we rather have those because we have acted rightly. We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act but a habit.”

We are not just human beings, we are human becomings. So, let’s be human well- becomings.

Manika Vassia (2016) Diet Coaching: The emerging components of the Dietitian’s skill set. 2nd International Congress on Cognitive Behavioural Coaching, Greece.

None.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

© . This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.