Advances in

eISSN: 2378-3168

Objective: In this study we tried to find out which would be the most important attitude-related factors that make the weight loss management difficult.

Methods: We discussed problems of weight loss attempts with 68 persons having tried to lose weight. 32 had been successful having managed to lose at least 5kg of their weight permanently; they formed “the successful group”. 36 had not been successful at all, forming “the non-successful group”. We compared the amount of harmful attitudes between these groups.

Results: During these discussions emerged 15 attitude-related factors that seemed to disturb successful weight loss and maintenance. These attitude-related factors were found significantly more often in the non-successful group as opposed to the successful group. The factors that seemed to disturb the attempts to lose weight were inertia (”laziness”)(IN), culinary attitude (CU), Depressive mood (DE), restlessness (RE), superiority attitude (SB), criticism (CR), bitterness (BI), food dependency (FD), experiencing general difficulties in weight loss (DI), impaired physical condition (IC), hunger (HG), incapacity (ICA), peer pressure (PP), lack of the time (LT) and unrealistic activity (UN). Statistically the most significant factors in this study were depressive mood (p=0.0018), food dependency (p=0.006), restlessness (p=0.035), bitterness (p=0.035) and inertia (p=0.23). Also one combination of three factors (criticism, experiencing general difficulties in weight loss and impaired physical condition) was statistically more abundant in the non-successful group (p=0.0299).

Conclusion: During a 30minute discussion there were found attitudes that are not beneficial to the weight loss management. The most disturbing attitudes in our study were depressive mood, food dependency, restlessness, bitterness and inertia. The existence of factors that alone were not statistically significantbetween the two studied groups became statistically significantas a combination.

Keywords: weight loss management, management of obesity, factors in weight loss, attitudes in weight loss

CU, culinary attitude; FD, food dependency; IC, impaired physical condition; PP, peer pressure; LT, lack of the time; UN, unrealistic activity; UHT, university hospital of turku; NS, non-successful group; IN, inertia; DE, depressive mood; RE, restlessness; SB, superiority attitude; CR, criticism; BI, bitterness; DI, experiencing general difficulties in weight loss; HG, hunger; ICA, incapacity

Some progress has been made in the treatment of obesity, but obesity still is a complex medical problem that requires a multimodal approach beyond merely advising patients to go on a calorie-reduced diet and start exercising.1 When treating obesity mere recommendations for lifestyle change are often insufficient.1 Obviously other factors must also be considered in the process. In our study we studied attitudes that would be different between persons having been successful in weight loss and maintenance and persons that had not managed to lose weight at all (Table 1).

Name of the factor |

A short description of the factor |

IN |

Laziness or lack of activity was felt. "Too much trouble", neutral mood, but enthusiasm is lacking. The subject expressed that dieting and weight loss efforts in general were too demanding. “I do not have the energy now.”” I do not want to be that meticulous about food.” Too much attention is needed to monitor my eating habits.”” Too much of a fuss!” |

CU |

Life was centered on the food in a manner that disturbed the weight loss process. Food was an important part of life. |

DE |

The subject told himself/herself about the low mood. The depressive mood was considered to be present only, when the subject admitted it. |

RE |

The person could not concentrate in the issue of losing weight. During consultation did not listen or ask questions. Focusing was lacking. |

SB |

The person felt he/she knew the issue already well enough, better than the health care- professionals. No-one could give anything new to the issue. Motivation to learn something new about weight loss management was lacking. |

CR |

The person interviewed felt the information given about weight loss or activity to support the person has not been good enough. |

BI |

Somebody has said or done something in the field of weight loss that had caused a feeling of insult. |

FD |

The patient felt that eating and an urge to eat too much was connected very tightly to any feeling or any circumstances or happening. |

DI |

Person felt that losing weight is just difficult for an unknown reason. Just feels difficult. |

IC |

The person felt that impaired health condition disturbed the weight loss efforts. |

HG |

Feeling hungry made losing weight difficult. |

ICA |

The person felt he/she did not know how to lose weight. |

PP |

The person interviewed felt that decisions in life were made by others |

LT |

Busy schedule or feeling of a busy schedule prevented proper efforts to lose weight |

UN |

Diets and weight loss efforts had been unrealistic. The person felt he/she had to try fad diets, cabbage-soup-diets or other extreme attempts |

Table 1 Factors found

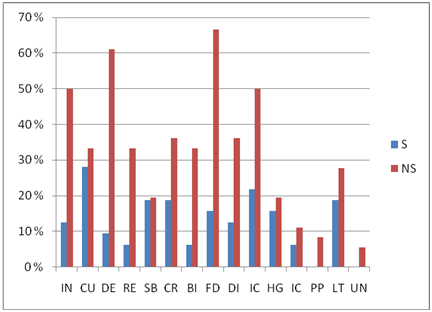

Thoughts and thinking patterns are understood as the central issue to the problem of obesity.2 The majority of weight loss therapies provide patients with a set of principles and techniques to modify eating and activity habits, but thinking patterns are considered essential. The purpose of the majority of weight loss therapies (e.g. all cognitive-behavioral approaches) is not to diagnose or eliminate psychiatric disorders. In our study we didn’t study psychiatric disorders but attitudes. Attitudes affect behavior, attitudes can be changed and cognitive change can effect behavior change.3 Therefore it is of importance to study the negatively impacted attitudes that would be more prominent within those who do not manage to lose weight than those who are successful in weight management. The identification of attitudes that are associated with failure to lose weight could enhance our understanding for the behaviors and prerequisites that are crucial in weight loss management(Figure 1)(Table 2).

Figure 1 Appearance of the factors in successful and in non-successful groups.

S=successful group, NS: Non-Successful Group; IN: Inertia; CU: Culinary Attitude; DE: Depressive Mood; RE: Restlessness; SB: Superiority Attitude; CR: Criticism; BI: Bitterness; FD: Food Dependency; DI: Experiencing General Difficulties in Weight Loss; IC: Impaired Physical Condition; HG: Hunger; ICA: Incapacity; PP: Peer Pressure; LT: Lack of the Time and UN: Unrealistic Activity

Name of the factor |

Successful group |

Non-successful group |

P-value (Comparison of the groups) |

IN |

4 (13%) |

18(50%) |

p=0.0233 |

CU |

9(28%) |

12(33%) |

p=0.6056 |

DE |

3(9%) |

22(61%) |

p=0.0018 |

RE |

2(6%) |

12(33%) |

p=0.0351 |

SB |

6(19%) |

8(20%) |

p=1.0000 |

CR |

6(19%) |

13(36%) |

p=0.2987 |

BI |

2(6%) |

12(33%) |

p=0.0351 |

FD |

5(16%) |

24(67%) |

p=0.0062 |

DI |

4(13%) |

13(36%) |

p=0.1026 |

IC |

7(22%) |

18(50%) |

p=0.1542 |

HG |

5(16%) |

7(19%) |

p=0.7648 |

ICA |

2(6%) |

4(11%) |

p=0.6809 |

PP |

0 |

3(8%) |

p=0.2467 |

LT |

6(19%) |

10(28%) |

p=0.5825 |

UN |

0 |

2(6%) |

p=0.4965 |

32 |

36 |

Table 2 Appearance of the factors within successful group and non-successful group. Fisher’s exact test was used

In our study the whole process of the weight loss was discussed with persons having tried to lose weight. We compared the group that had been good in maintaining the weight loss to those who had not been successful. Some of them had not managed to lose any weight at all. We utilized the data already collected in previous studies as the basis of the discussions and we also let the persons describe freely in their own words their opinions about difficulties and attitudes about weightloss. We consider the weight loss management as a chronic, continuous process and do not divide it into two phases of weight loss and maintenance. Findings from previous studies suggest some aspects that tend to be crucial components between a successful and non-successful weight management. We used these previous findings as the base for our study.

Level of motivation to change things in life is an important issue in weight management4 and that most certainly requires active attitudes. Controlling the weight requires activity5 and so does keeping record of the amount of food eaten.6 Our idea was that these activities might not be successful if inertia or “laziness”, criticism, incapacity or non-creative thinking pattern5 would be present. Inertia (“laziness”) was considered to be present in the discussion when the person had little intention or real serious activity when it came to trying to lose weight. There could be almost a total lack of eagerness to do something about the extra weight. There could also be complaining about the all too big an effort needed to lose weight. Superiority attitude was considered to be present, when the person expressed, that he/she already knows it all when it comes to losing weight. No new information was necessary or even existing anywhere. An attitude of superiority or pride prevailed. Criticism was considered to be present, when the person expressed that, the information given about weight loss or the activity to support the person had not been good enough. Incapacity was considered to be positive when knowing how to lose weight was lacking.

Food dependency with binge eating and tendency to eat to regulate mood have been considered problematic to weight management in previous studies.5,7 Food dependency was thus studied and was considered to be present, when eating and an urge to eat too much was connected very tightly to any feeling or any circumstances or happening. As food is a central topic in weight loss, culinary attitude was also asked. Culinary attitude was considered to be present when the person interviewed felt that the food was a central topic in conversations, in everyday life, a central activity in holidays and travels etc.

Association between obesity and depression has repeatedly been established. Obesity has been found to increase the risk of depression and in addition, depression has been found to be predictive of developing obesity.8–12 The patient was not asked about the diagnosis of depression or medication for depression. Anyone expressing the sadness concerning attempts to lose weight was included in this group. No psychological testing concerning depression was made. The low mood could emerge spontaneously in the conversation. It was also deliberately asked in the conversation to know whether this factor was present. Depressive mood was considered to be present, when the person told about the depressed mood or depressed thoughts considering losing weight or life situation in general.

We assumed that some of the patients who had not managed to lose weight would feel that they do not exactly know why they were not successful. This phenomenon was called experiencing general difficulties in weight loss-factor and itwas considered to be present, when the patient described the weight loss failures to be truly difficult to understand.

Much morbidityis associated with obesity.13 It is becoming clear that obesity is a low-grade inflammatory disorder. Many of the comorbidities may be related to this inflammatory process.14 This inflammatory state may be the mediator between obesity and fibromyalgia, spondyloarthropathy, rheumatoid arthritis and cardiovascular disease.15–17 Obesity is also often associated with sleep apnea, often causing chronic fatigue.18 So it seemed justified in our study to also discuss the role of the impaired health. Impaired physical condition was considered to be present when the person felt that the impaired health condition disturbed the attempts of weight loss.

In previous studies time management has proved to be an important issue in weight management.19 The lack of the time-factor was considered to be present as the patient felt his/her timetable was all too tight to do something about losing weight. A busy schedule or feeling of a busy schedule prevented proper weight loss efforts.

Restlessness and cynicism have been connected to unsuccessful weight loss management.20 Also patients reporting repeated dietary attempts have been found to be more prone to regain weight.Focusing has been found to be a crucial element in successful weight management.21 These findings were basis for discussions of bitterness and restlessness. Bitterness was considered to be present, when the person felt strongly that somebody has said or done something concerning weight loss or obesity that had caused a feeling of insult. This insult was of permanent type and came across very easily. Restlessness was considered to be present when the patient described several short-lived intentions of losing weight, felt nervous during the discussion, jumped from detail to detail and had difficulties to focus.

Struggling with hunger would lead to binge-eating.22 So we discussed also the feeling of hunger. Hunger was considered positive, when feeling hungry made losing weight difficult. Dichotomous thinking implying a simplified ‘black-and-white’ approach has been described to characterize weight regainers whereas more flexible thinking characterized the maintainers.5 This could lead to extreme attempts and unrealistic activity e.g. trying fad diets. The unrealistic activity-factorwas considered to be present, when diets and weight loss efforts had been unrealistic e.g. cabbage-soup-diets or other extreme attempts.

Peer pressure may influence food choices. It may play a part in what and how much a person eats. Social norms affect how much people eat. People’s food choses are clearly linked to their social identity. From these findings rose the issue of peer pressure in weight loss. The peer pressure- factor was considered to be present when other people influenced too much the decisions of the dieters when it came to eating or exercising. We also wanted to assess which of these attitude-related factors would be statistically most significant between successful group and non-successful group and could then be considered the most important factors. The study has been approved by the Ethical Council of South-Western Finland, Turku. (numberETMK 35/180/2010, study accepted nr. 532/10).

All together 68 persons were interviewed in this study by the same interviewer (HL).The persons interviewed were collected from the outpatients of University Hospital of Turku (UHT). We called random consecutive patients from the hospital patient lists. We accepted anyone who was willing to discuss with us in the phone or personally. All the patients had searched for treatment to their obesity as outpatients in the hospital over theyears. 32 persons interview had been successful, 36 had been not successful. We tried to find approximately the same number of successful dieters and non-successful dieters. The person was named as successful, if he/she had lost at least 5kg of weight intentionally in any conservative way. The amount of 5kg was randomly chosen. The weight loss in the successful group was 16±8,6kg. Only the weight that had not been gained back was counted. Median age was 53, 9±11, 7years at the time of the discussion, male16/68 and female 52/68.

The attitudes connected to difficulties in weight loss were searched in a 30-45minute conversation in the phone or personally. The patient was asked about the attitudes they had and difficulties they had encountered as they had tried to lose weight. No psychological testing or questionnaire was made, but the questioning process was in the form of a discussion. No psychological or psychiatric diagnosis was made. The patient was also encouraged to tell in their own words about their difficulties and experiences. The prevalence of the factors in both groups was calculated and statistically analyzed using Fisher’s exact test as a method, p<0.05 considered statistically significant

15 attitude-related factors, based mostly on previous studies that seemed to impair the results of the weight loss attempts were found in the discussions. Statistically the most significant factors seemed to be depression factor, food dependency factor, inertia factor, restlessness factor and bitterness factor. The appearance of these factors was statistically significant or very statistically significant (depression factor and food dependency) compared between successful and non-successful dieters. The Fisher`s exact test was used. The total amount of all existing factors was very significantly greater in the group of non-successful dieters (number of dieters=36) than in the group of successful dieters (number of dieters=32) as the Fisher´s exact test was used. The average appearance of factors in the successful group of dieters was 4±2, 4 factors, as with the non-successful group of dieters it was 12, 5±6, 6 factors. The total amount of factors in the successful group was 64, as it was 200 in the non-successful group the difference being extremely statistically significant(Table 3 & 4).

Name of the factor |

Statistical significance. Fisher’s exact test was used |

IN |

p=0.023, statistically significant |

DE |

p=0.0018, very statistically significant |

RE |

p=0.035, statistically significant |

BI |

p=0.035, statistically significant |

FD |

p=0.006, very statistically significant |

Combination of Three Factors: CR+DI+IC |

p=0.0299, statistically significant |

Table 3 Factors that the appearance of which differs statistically significantly even as a sole factor between successful and non-successful groups

Group |

Successful |

Non-Successful |

Total number of factors |

64 |

200 |

Number of persons |

32 |

36 |

Table 4 Total numbers of appearances of factors in the successful and non-successful groups Statistical significance in the difference of amount: p=0.0005, extremely statistically significant. Fisher’s exact test was used

There seems to be found attitude-related factors that have a negative impact on the weight loss process. The approximate analysis of factors present in a specific patient can obviously be done relatively easily during a meeting with the patient. No psychological in-depth analysis is needed. In-depth discussions last 180min5 and that is unrealistic in most outpatient settings to be used with all obese patients seeking for help. This would also require qualified personnel. The analysis of the existence of the factorslasts about 30-45minutes according to our study.

The most important factors seem to be linked to depression, food dependency, restlessness and bitterness. Also combination of factors seemed to be statistically significant (criticism, experiencing random difficulties in weight loss and impaired physical condition). We found a clear statistical significance between these two groups studied: those who had managed to lose weight had statistically extremelysignificantly less detrimental attitudes

Our study also emphasizes the holistic approach to weight management as a combination of factors appeared statistically more significantly in the non-successful group than in the successful group although no statistical significance was found to these factors as analyzed as a sole factor. Although there appears to be very few personality characteristic unique to obese persons,20,23 attitudes seem to differ. With respect to personality types and traits obese people represent a very heterogeneous population,24 but attitudes differ between those who are successful in weight management and those who are not.

As we are approaching the concept of continuous care model of obesity, it might be time to acknowledge that the problematic attitudes connected to weight loss and weight maintenance are the same. It has been speculated that the interaction of the factors is likely.25 Our study supports this assumption.

During a 30minute discussion with a patient seeking for help for his/her obesity there can be found attitudes that are not beneficial to the weight loss attempt and management. The detrimental attitudes concerning the whole weight loss process in our study (loss and maintenance) seem to be the same than detrimental attitudes studied in previous weight loss maintenance only studies. The most disturbing attitudes in our study were depressive mood, food dependency, restlessness, bitterness and inertia. None of these attitudes is necessarily stagnant, but they all can be prone to changes, which phenomenon could be used during the counseling for weight management. The combination of factors that is statistically more abundant in the non-successful group than in the successful group (criticism, experiencing random difficulties in weight loss and impaired physical condition) emphasizes the fact that the weight loss management is a multivariable and complex process and interaction between the factors may happen. There are several limitations to this study. The sample sizes are small. The groups were randomly selected and were not homogenous. The interviewing process is subjective. Further study is needed to understand the process.

We warmly thank Hilda Kauhanen Memorial Fund, Pori, Finland for the most generous financial support for this study. The Study Protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital District of Southwest Finland. This study has been approved by an Institutional Review Board and it has the authorization of the hospital (number ETMK 35/180/2010, study accepted nr. 532/10).

The author declares no conflict of interest.

© . This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.