eISSN: 2577-8250

Research Article Volume 5 Issue 1

University of Maine, USA

Correspondence: Minglei Zhang, Department of Communication and Journalism, University of Maine, Orono, ME, USA

Received: March 05, 2023 | Published: March 17, 2023

Citation: Zhang M. Gone with the sound: critical perspectives on studying imaginability of American cinematic experience in the “sound” era, 1927-1935. Art Human Open Acc J. 2023;5(1):75-79. DOI: 10.15406/ahoaj.2023.05.00190

This article explores the human-technology relationship during the transition from silent films to sound films in American history and analyzes how this specific technology has influenced film audiences’ experiences. The author revisits the importance of human-centered technology and uses the term “imaginability” to describe the likelihood for both spontaneous bodily responses and technologically cultivated thinking activities inspired by cinematic engagement. The article challenges the discourse of technology as progress while focusing on the audiences’ experience during their cinematic engagement. The author's hypothesis is that sound film provides a linear channel of synchronization and hence produces restrictions on the audience’s imagination by limiting their temporal and spatial sensibilities. This synchronized sound technology offers a streamlined audiovisual reality through matching sounds and images in real-time, leading to a shortened processing of images, sounds, and their interconnections. The transitions between filmmaking and cinematic presenting have also revolutionized theater design, leading to the liminality that describes the state of transitioning under this circumstance led by sound technology, which generates metrics, measuring how fast and how thoroughly technology conquers an outdated society by enforcing innovations. The article focuses on the interplay between the spectatorship that addresses the condition of viewing films and the sound consciousness led by the synchronized sound system as applied to filmmaking. The analysis of imaginability becomes measurable, descriptive, and referential. The author suggests that the preservation and scrutiny of silent films are urgent and necessary to recognize the values of silent film production and the audience’s cinematic experience during the silent film era.

Keywords: sound studies, cinematic experience, silent films, phenomenology, techno culture, subjectivity

“The advent of American talking movies is beyond comparison the fastest and most amazing revolution [in] the whole history of industrial revolutions.” —Fortune Magazine, October 1930

The film industry has experienced a unique development between the 1920s and 1930s as the talkie films gradually replaced the silent films and eventually became a standardized format of the cinematic experience for audiences. In each historical transition that demonstrates revolutionary changes in human civilization, technology has been the key force to empower these progresses. Likewise, the tendency of viewing new technology as a game changer is applicable to the emergence of talkie films. Simultaneously, discourse surrounding technology has dominated the public culture and dictated social superiority from a pro-technological perspective. In other words, discourse of technology as progress is common in human history, which has connections to discourse around Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution. The general notion of evolutionary thought directly speaks to the linear development of species in both macro and micro manners. When it comes to the film industry’s development, synchronization and amplification, as long-expected “audiovisual” technologies, both predict and assure filmmakers’ capabilities of producing believable pictures as well as narrating a convincing “virtual reality.” At a macro level of social awakening, new technology engenders the role of gatekeeper for embracing modernity, which automatically and ultimately enables an evolutionary perspective reflecting upon social lives, for better or worse. Thus, according to Richard Weaver’s depiction, technology becomes a “god term” because technology discourse centralizes its influence for social change by subordinating other social expressions.1 On the other hand, people’s interpretation of how technology revolutionizes their daily lives vividly demonstrates the trajectory of progress led by technology in everyday culture.

Given the booming economy driven by technology in the 21st century, regarding technology as an almighty progress has become more pervasive and phenomenal. Therefore, the image of technology is metaphorized as legendary and heroic. For example, at the recent Apple event that took place virtually in April 2021, the company announced its new production lines and future designs. Apple’s CEO coherently framed the technology company’s next-generation products as faster, more advanced, and more spectacular. Basically, the message was if we are going somewhere in the future, it must be better in every sense of the word. The betterment of technology indicates its inherited connection to evolutionary ideologies which easily allow people to overlook the concurrent downsides. With industrial revolutions, we have also experienced detrimental ecological consequences as leading concerns. By the same token, introducing seemingly more advanced synchronized sound technology into our modern lives has also brought some undesirable outcomes that are nearly invisible in the pro-technology mainstream culture.

Through a critical historical perspective, I will focus on the human-technology relationship during the transition from silent films to sound films in American history and analyze how this specific technology has influenced film audiences’ multilayered experiences. My research revisits the importance of human-centered technology. Therefore, I will use the term “imaginability” to describe the likelihood for both spontaneous bodily responses and technologically cultivated thinking activities inspired by cinematic engagement. The time period selected for this study ranges from 1927 to 1935. The starting year marks the first commercially successful feature-length film originally released as a talkie, The Jazz Singer.2 The year of 1935 signifies the last silent film produced in Hollywood, Legong: Dance of the Virgins. This period covers the transition process within the film industry surrounding sound technology, synthesizes the commercial value as a priority in contributing to the film markets, and indicates the competition in two models of cinematic presentation.

By studying the contextualization of imaginability in specific historical contexts, I will revisit the discourse of technology as progress while focusing on the audiences’ experience during their cinematic engagement. My hypothesis is that sound film provides a singular channel of synchronization and hence produces restrictions on the audience’s imagination by limiting their time and space for reaction. This synchronized sound technology offers a streamlined audiovisual reality through matching sounds and images in real time. Consequently, a concrete representation of film allows the audience to catch up with the ongoing scenes without any asynchronous intervals and shortens the audience’s processing of images, sounds, and their interconnections in between. The transitions between filmmaking and cinematic presenting have also revolutionized theater design. Without the accompaniments of live music bands, commonly experienced in the silent film era, an audience’s experience in the sound era becomes compact and highly concentrated on screen. The liminality that describes the state of transitioning under this circumstance led by sound technology therefore generates metrics, measuring how fast and how thoroughly technology conquers an outdated society by enforcing innovations. Therefore, we have paid too much attention to the glamour of technology to consider the mundane negativity that it may bring at the same time.

1Ian Roderick, Critical Discourse Studies and Technology: A Multimodal Approach to Analysing Technoculture, Bloomsbury Advances in Critical Discourse Studies (London; New York: Bloomsbury Academic, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing, 2016;93.

2Emily Thompson, “Wiring the World: Acoustical Engineers and the Empire of Sound in the Motion Picture Industry, 1927–1930,” in Hearing Cultures: Essays on Sound, Listening, and Modernity, ed. Veit Erlmann, Wenner-Gren, International Symposium Series (Oxford; New York: Berg, 2004;196.

The focus of the historical comparative analysis in this study lies in the film productions released in both silent and sound periods. A report published by the U.S. Library of Congress, which holds the largest silent film collection, shockingly noted that ninety percent of the films made during the silent era have disintegrated and permanently disappeared.3 However, the more alarming news in this report reveals the disturbing situation in cultural and historical preservation: “Nearly all sound films from the nitrate era of the 1930s and 1940s survive because they had commercial value for television in the 1950s and new copies were made while the negatives were still intact. Unfortunately, silent films had no such widespread commercial value then or now.”4 Such an evaluation driven by linear pro-technological thinking is deeply concerning at least because it fails to recognize the values of silent film production and, more importantly, the audience’s cinematic experience during the silent film era.

In addition to researching the American Silent Feature Film Database, maintained by the Library of Congress, it is also fruitful to compare the same film title restored at different times with different sound technology to contribute to insights regarding the audience’s cinematic experience.5 For example, Metropolis, a feature produced during the silent film era in 1927, was later restored with varied sound technologies including synchronization added into several versions.6 Although the production and reproduction of Metropolis was originally in German, this interpretation and reenactment of the change from the silent to the sound era remains pertinent in exploring the audience’s cinematic experience. Additionally, including the media coverage of professional film critics during the given years can also contribute to the evaluation of film and the film medium through the eyes of people who lived in specific contexts.7

While the invention of Vitaphone and its subsequent innovations of sound technology changed the film industry and its audience from an era claiming that “seeing is believing” to the one that emphasizes “hearing is believing,” imaginability as a unified concept in interpreting the audience’s cinematic experience integrated this historical transition into a non-linear spectrum. In outlining this research project, I will utilize thematic categorification surrounding the conceptualization of imaginability. This approach will allow me to identify the distinctive features that emerged in both stages of film development. In the meantime, through an integrative survey focusing on the evaluation of imaginability, the normative constituents shared by films produced in both eras will help address the cultural and historical values in silent films, ultimately demanding preservation and scrutiny of silent films in an urgent manner.

3Pierce, The Survival of American Silent Feature Films, 3; Peter Kobel, Silent Movies: The Birth of Film and the Triumph of Movie Culture, 1st ed (New York: Little, Brown and Co); 2007;8.

4Ibid., 5.

5For more information about the database, see https://www.loc.gov/programs/national-film-preservation-board/preservation-research/silent-film-database/.

6John Clute and Peter Nicholls, eds., The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin). 1995;805.

7Duane E Lundy, Alivia C Crowe, Alyssa J Turner. The Shape of Aesthetic Quality: Professional Film Critics’ Rating Distributions,” Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts. 2016;10:1.

The emergence of being “sound conscious” in American contemporary history originated with the inventions of the telephone and phonograph.8 The earliest synchronized sound system, Vitaphone, was applied to the film Don Juan at the Warner Theater in New York on August 7, 1926.9 Film Daily described it as “electrical” and suggested that “through the industry the event was hailed as presaging a new era in entertainment.”10 However, Don Juan was not technically a talkie film that maintained synchronization between camera, phonograph, and projector but only had a synchronized score.11 The beginning of the transition to talkie films has often been dated back to the subsequent Vitaphone feature, The Jazz Singer in 1927.12 The Vitaphone was a sound-on-disc system utilized by the Warner Brothers to produce talkie films in the mid 1920s.13 As Emily Thompson recounted regarding the historical significance when The Jazz Singer first entered the public’s eyes, the future of the film market was reshuffled by this new technology.

[In The Jazz Singer,] Jolson’s character, Jack, is a modern, jazz-loving musician. His father, a tradition- bound cantor, disowns his sacrilegious son, and the climactic scene of the film occurs when Jack now a star about to debut on Broadway returns home to reconcile with his parents. In the famous talking sequence, his mother embraces his return, and he woos her with snappy conversation and a jazzy melody. When the father encounters their revelry, however, he indignantly cries out, “Silence!” and the soundtrack goes silent for several long seconds before the old-fashioned background music returns.14

As Thompson has shown, “the fictional narrative of the film itself reinforced its technologically revolutionary impact.”15 Focusing on these sound technologies, such as telephone, phonograph, and Vitaphone, the editors of the New York Time in 1930 called attention to the relationship between the soundscape and modernity. The newspaper emphasized that “the listening habit” became an important constituent of “modern life.”16 The formation of this modern sound consciousness charts the dramatic transformation in “what people heard, and it explores equally significant changes in the ways that people listened to those sounds.”17 According to Thompson, what people heard was “a new kind of sound that was the product of modern technology.”18 Consequently, “they listened in ways that acknowledged this fact, as critical consumers of aural commodities.”19 The sounds themselves were increasingly “the result of technology mediation”20 and problematized the ideology of authenticity, which naturalized the audience’s perception of their cinematic experiences.

The American engineers who led this sound technology revolution “perceived themselves to be on a technological mission,” and their goal was to get the world “in sync” with modern America.21 Through this synchronous sound technology, the film industry in the late 1920s and early 1930s no longer continued their passion of producing silent films. According to David Pierce, the silent cinema was never “a primitive style of filmmaking, waiting for better technology to appear.”22 Instead, silent film was “an alternative form of storytelling, with artistic triumphs equivalent to or greater than those of the sound films that followed.”23 Pierce tracked the development of silent film in history and commented that “few art forms emerged as quickly, came to an end as suddenly, or vanished more completely than the silent film.”24 This comment not only reveals a classical pattern in linear historical development in which a successful transition often requires the enrichment of the newer technology and leaves old technology far behind, but also raises serious concerns about the lack of in-depth examination of these old technologies because of their brief duration. In the case of silent films, when sound technology drastically captures the public attention, the replacement of silent film is the only means of finalizing and justifying this transition to its full mission of modernization. Thus, historical replacement indicates some sense of domination when the newer technology minimizes the chance of negotiating coexistence with the old technology and fully conquers modernization, bringing it to its own domain. By recognizing this pattern led by the linear perspective of regarding technology as progress in historical development, I will revisit the brief but critical period in modern history when sound film quickly replaced the silent film.

My research questions focus on the interplay between the spectatorship that addresses the condition of viewing films and the sound consciousness led by the synchronized sound system as applied to filmmaking.25 As the audience has remained under the influence of the cinematic experience, studying how this modernization impacted the film audience through the lens of imaginability opens new space to discuss the complexity of spectatorship in relation to filmmaking, the ambivalence of discourse surrounding technology as progress, and the recontextualization of modernity regarding our everyday culture.

8Thompson, “Wiring the World,” 191.

9Jessica Taylor, “‘Speaking Shadows’: A History of the Voice in the Transition from Silent to Sound Film in the United States,” Journal of Linguistic Anthropology. 2009;19(1): 5.

10Ibid.

11Thompson, “Wiring the World,” 195.

12Taylor, “‘Speaking Shadows,’” 5.

13Thompson, “Wiring the World,” 194.

14Ibid., 196.

15Ibid.

16Ibid., 191.

17Emily Thompson, The Soundscape of Modernity: Architectural Acoustics and the Culture of Listening in America, 1900 - 1933, 1. paperback ed., Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press; 2008.

18Ibid.

19Ibid.

20Ibid. 2; Taylor, “‘Speaking Shadows,’” 5.

21Thompson, “Wiring the World,” 192.

22David Pierce, The Survival of American Silent Feature Films, 1912-1929, CLIR Publication, no. 158 (Washington, D.C: Council on Library and Information Resources and The Library of Congress, 2013;5).

23Ibid.

24Ibid.

25Annette Kuhn and Guy Westwell, A Dictionary of Film Studies, 1st ed, Oxford Paperback Reference (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012;1378).

The investigation of the audience’s cinematic experience requires discussion of how to approach some key terms in film studies. For example, the contextualization of spectacle and spectatorship essentially strengthens specific temporal ties regarding film development, both historically and technically. Giving enough weight to these concepts is helpful in identifying significant elements at various stages of silent and sound film transitions and in tracking the changing conceptualization of these terms across time. The transitional trajectories from silent to sound film are not separate but interconnected through a hybrid mode of convergence in film history. Furthermore, imaginability as a key contribution to the audience’s cinematic experience necessitates theorization to acknowledge the long-overlooked aspect of recentralizing human experience within the technological revolution led by the capitalistic market.

Spectacle, spectatorship, and the cinematic experience

The impression of spectacle in film studies engenders a particular cinematic experience for the audience. In the late 1890s, cinema itself was commonly regarded as an “impressive spectacle.” Also, during the silent era, spectacle was often a central selling point for advertisement in high-budget films.26 As the film industry expanded its genres during development, spectacle also indicated a feature of a certain enduring film genres, for example, “[in] action film (stunts, fights, car chases, male bodies), the musical (song-and-dance sequences, bodies in motion, complex choreography), science fiction (special effects, fully realized future worlds), the war film (explosions, military technology, wounded bodies), and the history film (casts of thousands, large sets).”27 In terms of technology in filmmaking, foreground special effects work, such as a synchronized sound system and computer-generated imagery (CGI), also made spectacle a central attraction.28 Additionally, spectacle can be a critical concept. Guy DeBord in his Society of the Spectacle (1967) argues that film, as a constituent part of the wider mass media, is “a spectacle that functions as a palliative, distracting people from social and political engagement.”29 While the general notion of spectatorship rooted in the state of “being present at, and looking at a spectacle,” there are some more precise meanings embedded in film theories that consider “the operations at work in our engagement with, and comprehension of, the sights and sounds that make up the cinematic experience.”30 In other words, spectatorship summarizes an embodied experience during the audience’s cinematic immergence that reflects “an emergent visual aesthetic with an attendant form of viewing experience.”31 The inexhaustibility of exploring the depth of this immergence from the audience’s perspective generates fruitful conversations about how spectacles developed by specific film technological narratives influence the contingent spectatorship and vice versa.

The sound in silent film and the silence in sound film

It seems an undeniable fact that silent film was followed by sound. However, the silent film was not entirely soundless; it made itself heard through intertitles and musical accompaniment. During the silent film era, these intertitles, also known as title cards, were displayed at various points to help convey character dialogue and essential descriptive information for the film storytelling.32 The musical accompaniment in silent films often included “live or recorded music, sound effects, and other accompaniment.”33 These sound components, which collaborated to provide vivid entertainment later in the “sound” era, now were fully presented with the screen-display only through synchronization.34 These two different models of filmmaking introduce distinct expectations for the audience’s cinematic experience. As for the comparison regarding sound effects, Peter Kobel suggests that “if you see a silent film as it was meant to be seen, with live music, you certainly will not feel it is in any way inferior to a talkie.”35 Kobel’s claim highlights the role of navigating the historical stance in comparing spectacles as they were in their specific historical contexts. Otherwise, as he continues, “A crashing chord from a symphony orchestra outdoes even Dolby stereo!”36

During the “sound” era, modern filmmakers have rediscovered the potential of silence when weaving their narratives. For example, the term “filmic silence” often describes a scene in which “only a quiet ambient track is present” to create suspenseful sequences. Consequently, silence as a metaphor or cinematic device has been incorporated into modern techniques in filmmaking.37 As Donald Richie reviews the meaning of silence in the “sound era,” she concludes that “true filmic silence only comes into existence with the advent of the sound film.”38 Richie’s observation revolutionizes the role of silence in film history in response to a linear perspective that views silence as bygone and forgotten because of the emergent sound technology. She also recognizes the value of silence that helps construct the spectacle as well as the multilayered nature of silence in sound films. Identifying the historical development of film through the terms “silent” and “sound” inevitably makes silence and sound become spectacles in their own historical spectatorship.

What to imagine, how to imagine, and why to imagine

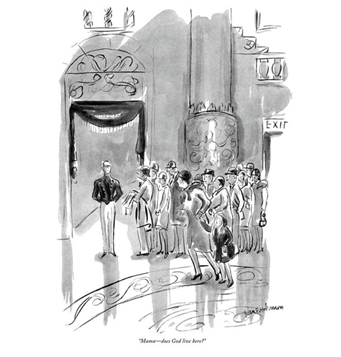

The conceptualization of imaginability is not transcendental so much as bodily in everyday culture. However, our perception of the newer technology often includes a feeling of ecstasy from being amazed by its extraordinariness. The New Yorker published a cartoon in 1929 (Figure 1) depicting a little girl’s reaction to a modern metropolitan theater.39 The underlined meaning echoes Weaver’s “god term” when describing the power of technology in revolutionizing people’s social lives.40 Thus, examining the quality of imagination is within the audience’s lived cinematic experience. Such an investigation necessitates a perspective of embodiment rather than a god’s view. The evaluation of imaginability at different stages in film history seeks to answer specific questions regarding the audience’s cinematic experience. In this historiographical study, I will focus on studying:

Figure 1 “Mama—Does God Live Here?” Little girl to her mother, at Radio City Music Hall.

(Cartoon by Helen E. Hokinson, The New Yorker, February 23, 1929, Condé Nast Collection, https://condenaststore.com/featured/does-god-live-here-helen-e-hokinson.html)

What to Imagine: the elements presented in the audiovisual film production to the audience;

How to Imagine: the processes of imagination prescribed in the filmic representation to the audience; and

Why to Imagine: the motivational cues available from the film display for the audience’s imagination.

By answering these questions during the comparative analysis of a specific period in film history, I will enrich the concept of imaginability with detailed audiovisual narratives in filmmaking from the audience’s eyes. In this manner, the analysis of imaginability becomes measurable, descriptive, and referential.

26Ibid. 1066.

27Ibid. 1067.

28Ibid.

29Guy DeBord, The Society of the Spectacle, Reprint (Detroit, Mich: Black & Red). 2010

30Kuhn and Westwell, A Dictionary of Film Studies, 1378.

31Brian R Jacobson, “Found Memories of Film History: Industry in a Post-Industrial World, Cinema in a Post-Filmic Age,” in New Silent Cinema, eds. Paul Flaig and Katherine Groo, AFI Film Readers (New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2016), 609; Miriam Hansen, Babel and Babylon: Spectatorship in American Silent Film (Harvard University Press). 1991.

32Anthony Slide and Anthony Slide, The New Historical Dictionary of the American Film Industry, 1st ed. (Lanham, Md: Scarecrow Press). 2001;197.

33Taylor, “‘Speaking Shadows,’” 5.

34Paula Marantz Cohen, Silent Film & the Triumph of the American Myth (Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press). 2001;161.

35Peter Kobel, Silent Movies: The Birth of Film and the Triumph of Movie Culture, 1st ed (New York: Little, Brown and Co). 2007;12.

36Ibid.

37Shigehiko Hasumi, “Fiction and the ‘Unrepresentable’: All Movies Are but Variants on the Silent Film,” Theory, Culture & Society 26, no. 2–3 (March 1, 2009): 316, https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276409103110; Claus Tieber and Anna Katharina Windisch, The Sounds of Silent Films: New Perspectives on History, Theory and Practice (Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire; New York, New York: Palgrave Macmillan). 2014;214.

38Donald Richie, “Notes on the Film Music of Takemitsu Tōru,” Contemporary Music Review. 2002;21(4):7.

39Helen E Hokinson, “Mama—Does God Live Here?” The New Yorker, February 23, 1929. https://condenaststore.com/featured/does-god-live-here-helen-e-hokinson.html.

40Roderick, Critical Discourse Studies and Technology, 93; Robert Sklar, Movie-Made America: A Cultural History of American Movies, (New York: Vintage Books, 1994), 277; Donna Kornhaber, Silent Film: A Very Short Introduction, (New York, NY: Oxford University Press). 2020;227.

The transition from silent films to sound films in the film industry has been a significant milestone in the history of cinema, as sound technology revolutionized the cinematic experience. This article has explored the impact of sound technology on the audience's cinematic experience during this transition period. The author’s concept of imaginability, which describes the likelihood of spontaneous bodily responses and technologically cultivated thinking activities inspired by cinematic engagement, has been used to examine this impact. The author’s hypothesis that sound film provides a singular channel of synchronization and hence produces restrictions on the audience’s imagination by limiting their time and space for reaction has been analyzed. The analysis of the article highlights the importance of human-centered technology and challenges the discourse of technology as progress, emphasizing the need to recognize the values of silent film production and the audience’s cinematic experience during the silent film era. The author's suggestions for the preservation and scrutiny of silent films are particularly relevant in light of the alarming situation in cultural and historical preservation, as ninety percent of the films made during the silent era have disintegrated and permanently disappeared.

The article’s strength lies in its focus on the interplay between the spectatorship that addresses the condition of viewing films and the sound consciousness led by the synchronized sound system as applied to filmmaking. The author’s approach to identifying the distinctive features that emerged in both stages of film development through thematic categorization surrounding the conceptualization of imaginability is innovative and contributes to the understanding of the audience’s cinematic experience during this transition period. However, the article could benefit from further analysis of the role of gender and race in the audience’s cinematic experience during this transition period. The article’s discussion of the American engineers who led this sound technology revolution and their goal to get the world “in sync” with modern America suggests the need for a critical examination of the cultural and social implications of this sound technology revolution. Further research in this area could provide valuable insights into the impact of sound technology on the audience’s cinematic experience and its broader social and cultural implications. In conclusion, this article provides a valuable contribution to the understanding of the audience’s cinematic experience during the transition from silent films to sound films in American history. The author’s concept of imaginability and thematic categorization surrounding its conceptualization provide a framework for analyzing the impact of sound technology on the audience’s cinematic experience. The article’s emphasis on the importance of human-centered technology and the need for the preservation and scrutiny of silent films is a timely reminder of the cultural and historical value of these films. Further research in this area could provide valuable insights into the broader social and cultural implications of this sound technology revolution.

None.

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

This work received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

©2023 Zhang. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.