eISSN: 2577-8250

Review Article Volume 3 Issue 3

Department of Psychopedagogy, University of Costa Rica, Costa Rica

Correspondence: Claire de Mézerville, Department of Psychopedagogy, University of Costa Rica, San Pedro, Montes de Oca San José, Costa Rica, Tel +50687022841

Received: May 20, 2019 | Published: June 3, 2019

Citation: Mézerville C. Fostering resilience in Costa Rican teachers: an analysis from a restorative practices perspective. Art Human Open Acc J.2019;3(3):150?154. DOI: 10.15406/ahoaj.2019.03.00123

This opinion paper explores the importance of fostering resiliency in Costa Rican high school teachers. Resilience in educational settings is analysed from the perspective of restorative practices, understood as proactive actions to strengthen the school community through repairing harm and restoring human relationships. Restorative practices based on principles like high control and high support, restorative questioning and positive affect will be described. Teachers’ resilience will be explored through the models of compassionate witnessing.1 and the relational care ladder.2 Teachers that are capable of fostering resilience development with their students in their own classrooms will become resilient themselves. Community based approaches are acknowledged as well as the necessary involvement of school systems and policy makers. Costa Rica’s results from the latest report on the State of Education3 will identify particular issues where teachers’ resilience is relevant in order to prevent burnout, promote student permanence and increase life skills such as self care and appropriate attention to high need - high risk students.

This paper addresses a restorative approach with Costa Rican students from the perspective of teachers, and their own strengths and needs. This reflection intends to stress the standpoint of the adults that work with them and their responsibility in the fostering of a school climate that responds to their realities and that nurtures their particular potential. This paper focuses on teacher's perspective, and how a restorative approach can improve the school community, the chances for resilience in the students and the wellbeing of the adults that work with them.

Teachers that deal with a high-risk and high-need population often experience vulnerability.4 This population has plenty of talent, generosity and wisdom manifested on the practices of men and women that teach youth in very challenging situations. They don’t only teach math or social studies, but they teach courage and patience.5 Still, burnout is an ever-present risk in those whose work resides on accompanying people. Burnout is more of a threat to those that do things FOR people, than in would be for those that work WITH them. Many teachers struggle in dealing with extreme situations. Systems often expect of a teacher the skills needed to deal with social and emotional situations, yet the professional development received might have not offered them the tools to do so.3

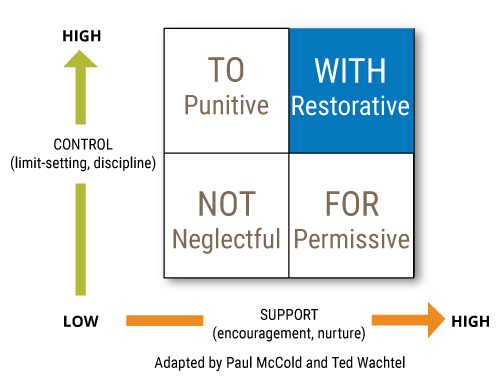

Teachers that experience burnout, depression or generalized anxiety might incur in neglectful practices within the school setting. Costello, Wachtel6 explain an authoritative approach to education through the Social Discipline Window (Figure 1), stating that educational practices that are both “low in control” and “low in support” would be a neglectful practices. Yet, neglectful practice doesn’t necessarily mean neglectful people. From a restorative justice perspective Braithwaite7 stresses the importance of separating the deed from the doer. This paper will address the importance of sensitizing and educating professionals, as well as offering them tools as a mean to support adults that teach populations in Costa Rican schools.

Figure 1 Social discipline window. From Wachte T.6

Sensitizing and educating about the social, neurological and pedagogical aspects of students could be the first step to improve teachers’ skills when dealing with them. For example, Perry & Szalavitz8 describe their neurosequential approach to trauma as a way to understand the lack in development that deprivation has on children in high risk and high need situations. Their approach targets their need to catch up with the deficits experienced on their early years and that has a significant impact on their cognitive processing, language, motor skills and behavior. To understand this leads to the possibility that misbehavior might be the reflection of an emotional age that doesn’t match the chronological age of the student. This is helpful to respond with empathy that is empowered by knowledge. It sensitizes teachers and encourages them to reach out to other system’s aids: special educational needs, counseling and other interdisciplinary work. According to Costa Rica’s 2017 State of the Education, teachers that foster mutual educational exchanges and promote positive relationships within the classroom have better quality in student learning.3 This goes beyond teaching style: it involves skills that are necessary for everyone involved in education. However, for these skills to be identified as relevant, is necessary to contribute with processes that sensitize educators about them. Sensitizing and educating are ways to empower teachers, which does not mean to ask them to do everything: on the contrary, it represents an invitation for them to become articulated within an educational community that has a responsibility towards vulnerable youth. Self-care and life skills should be an important part of teacher’s personal and professional growth.

Education as part of this process of professional development also fosters curiosity instead of judgment by helping teachers to understand misbehavior as a symptom of a deeper reality, instead of as a mere offensive action. Positive Behavioral Interventions in School (PBIS) approaches have been exploring this for years: Hoffman’s description of brain based learning is a good illustration of the importance of human interactions in the process of complex learning.9 When teachers understand that visual, auditory and motor skills are crucial to connect with learning processes, they will understand learning challenges, not just as defiance, but as real obstacles to be overcome in order to offer students the joy of learning. In overcoming these obstacles, it turns out that teachers and learners are on the same team instead of against each other. Jensen10 describes it very well when he says: “Some teachers perceive certain behaviors typical of low-SES children as “acting out”, when often the behavior is a symptom of the effects of poverty and indicates a condition such as chronic stress disorder. (…) In the classroom, this translates into blurting, acting before asking permission, and forgetting what to do next.”10

Sensitizing and educating teachers will necessarily involve offering them support through interdisciplinary work, training and facilitating circles with the staff. These are practical ways to balance the expectations they must respond to with support regarding the day-to-day challenges that they face. To promote this skills means that resilience is not merely a task for teachers, but a personal challenge: teachers need to become resilient themselves.

Common shock is a term applied to understand the effects of witnessing violence and violation: “adults observe violent acts, are affected by them, and yet may or not even register what is going on.”1 Teachers that work with high-need and high-risk populations are exposed to common shock. The author differentiates the experience: “there are two sides to the witnessing coin: one in which we are shocked, and the other in which we know what to do”.1 The shock involved in working with students in vulnerable situations will develop into negative affects and symptoms if they don’t know how to respond.

The personal and professional development required for this is sometimes an expectation teachers might not be prepared to meet. Teacher’s roles can become very confusing. They are expected to teach a subject and get students to show they know it in standardized tests. They are also expected to cover a measure of content in a limited amount of time. They are also expected by social scientists and policy makers to respond to student’s social and emotional needs. To respond to all of these expectations can become, to some of them, more of an idealistic illusion and not so much a day to day practice. Where to start? How to prioritize?

Restorative practices offer concrete responses to these questions. Restorative practices will be defined here as “non-punitive disciplinary responses that focus on repairing harm done to relationships and people, developing solutions by engaging all persons affected by a harm, and accountability” (U.S. Department of Education, 2014, p. 24, quoted by Gross, 2016, p. 42). They are based on a model oriented to the importance of strengthening community and building social capital through restoring human relationships and repairing harm when it occurs.6 They ask of teachers to revise their language and incorporate affective statements. They encourage proactive actions such as circles and student participation. Restorative practices also offer tools for conflict resolution, such as restorative questions that separate deed from doer and focus on repairing harm.11

Still, what happens when a student has severe cognitive difficulties or language barriers? What about the student whose neurobehavioral profile seems like his behavior is out of his control? Jensen10 describes impulsivity and disruptive behaviors as the results of a brain that didn’t have the conditions to develop impulse control. Hansberry12 talks about “Bradley”, in a case study that describes a kid with Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). The author talks about his teacher, “Lydia”, and says: Deep in Lydia’s brain, her caudate nucleus screams “That kid deserves a long stay in detention!”, but Lydia has been teaching kids with tricky behaviors for far too long to give into instinctive “tit for tat” responses (decisions to exact revenge have been shown to show a rush of activity in the caudate nucleus).12

It is very telling that Lydia and Bradley come from the case study in Hansberry’s12 essay titled: “They Suck, School Sucks, I Suck: The secret emotional life of a child with a brain that learns differently”. Rojas13 explains how inclusive education needs to focus more on dealing with the learning barriers in a diverse environment instead of focusing on a student-deficit-oriented model. Yet, exclusion and violence still represent a significant problem in some of Costa Rican school communities. According to Costa Rica’s state of the education, inequity is still significant in public high schools, with school climate and home income being the most important correlated factors.3 Teachers and students that experience healthy interactions and positive affect have more opportunities to thrive in the teaching-learning dynamic. However, high risk and high need situations will trigger affective reactions related with isolation, self sabotage, shame and hostility. George14 describes the spiral of shame when shame is triggered in students and teachers. Many of these cases will involve a child with a brain that learns differently.15 This usually implicates conditions such as deficient support from home, and dealing with some physical deprivations (nutrition, sleep, etc.).10 Perhaps the student has also been victim of physical and/or sexual violence.

George15 makes a vivid description of how shame shown in the classroom can spiral triggering shame in the teacher who, in response, also reacts avoiding, attacking, isolating or attacking self. This can, very easily, spin out of control, especially in communities vulnerable to violence. It can be very confusing for teachers to know how to react to misbehavior if they are not given the tools to do so. To understand shame as the trigger of bad behavior, and to know that shame can be responded to in an empathetic way that goes to the root of the problem, is key for someone that must work with a challenging student every day. It responds to the hopes that teachers may become those caring and dependable adults that high-risk students desperately need.

Restorative questioning, as described by Costello et al.11 is an empowering tool that challenges teacher’s mindset, by the premise of letting the student talk, and by talking, questioning himself or herself, elaborating and developing a sense of connection and validation. Restorative questions are questions selected or adapted from two sets of standard questions designed to challenge the negative behavior of the wrongdoer and to engage those who were harmed.16

Questions foster the Proximal Development Zone described by Vigotsky17 and offer a structured jumpstart for teachers that while they get acquainted with a restorative approach. Of course, questioning, as restorative as it may be, will find important challenges when we face students with significant limitations regarding cognitive processing, vocabulary and language. In situations when verbal elaboration is difficult, still active listening and working WITH the student in the pursuit of a solution to a problem, will build a sense of connection with an adult that actively listened and sat with the student to process what happened. And in that way, deals restoratively with shame.

For this very reason, understanding the common shock involved in teaching high-risk and high-need students may empower teachers to turn vulnerability into compassionate witnessing: the witnessing in which they will know what to do.1 Compassionate witnessing will be a path for teachers to become more resilient and prepared to face the realities of their school communities.

Weingarten1 describes compassionate witnessing as a witness position in which the person is aware of the violence and violation that is taking place and is also empowered to do something about it. She says: “If we are aware, we have choices” (p. 15), and also, “We can learn to transform passive, inadvertent, or unintentional witnessing into active acts of compassionate witnessing” (p. 11). There is always something to be done in the awareness of violence. The author describes a grid where she correlates awareness with empowerment: compassionate witnessing is when, as witnesses, teachers position themselves in a high awareness and high empowerment position (Figure 2).1

Figure 2 Changes in witness positions. Adapted from Weingarten K.1

Compassionate witnessing is not an individualistic response. In a more recent article, Weingarten18 describes the social and relational processes that influence our witnessing positions: Any of us may experience any of the four positions as one only we are responsible for having made happen, as if the position is independent of the social and relational processes that, in fact, “put” us there. These positions are not individual achievements but arise within the same discursive constraints that impact any other of our social locations.18

Compassionate witnessing in classrooms with high-risk and high-need students involves a systemic response. A perspective of lone rangers on their quest to “save the kids” is unrealistic and unhealthy for educators. When teachers understand their role as members of an educational community that also has a responsibility as a setting in charge of minors. The expectation laid on teachers about fostering Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) is a collective initiative that fuels on the belief that a child will learn better thanks to SEL. That notion is not new. Sylwester mentioned it almost 25 years ago: “Schools should focus more on metacognitive activities that encourage students to talk about their emotions, listen to their classmates' feelings, and think about the motivations of people who enter their curricular world.” (Sylwester, 1994). Should teacher’s trainings do that as well?

Costa Rica’s current focus from educational policies on PBIS.3,19 Comes from the belief that the school setting is the instance with the opportunity to respond to violence and violation. Schools may contribute in the “making up for” the particular needs that students experienced in their settings. Kennedy & Kennedy20 recommended this when they said that the “use of traditional behavioral interventions with students combined with attachment-oriented strategies may provide the best long-term outcomes.” (p. 253). These are all opportunities for proactive practices that will make a difference in a child’s life. This level of awareness is fundamental so that restorative practices find their true meaning.

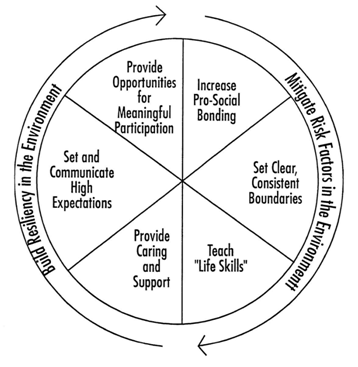

In order for this to work in a day to day basis, it must be based on a model that knows the “what” and goes to the “how”. Henderson & Millstein21 claim that a resilient school environment offers care and support, promotes high expectations, offers opportunities for students participation, increases prosocial bonding, sets clear boundaries and teaches life skills (Figure 3). Restorative practices, as a model, are based on high control and high support,11 fair processes based on participation, leadership transparency and expectation clarity6 and building a strong and affective sense of belonging.14 These two models represent the task at hand for teachers: they illustrate the what -resilience fostering environment- and the how -restorative practices.

Figure 3 Resiliency wheel. Adapted from Henderson N & Milstein MM.21

Restorative practices are a way to reduce risk factors and improve safety in the classroom. They also foster resiliency and facilitate SEL. According to Richardson,22 environmental factors influence and shape the brain: “Behavioral interventions are biological”, he stated. He mentions how the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex has much to do with positive affect and positive affect predicts lower evening of cortisol in adolescents. It becomes clear that negative emotion will interfere with cognitive function and maximizing positive affect will improve learning. How can teachers use this knowledge? A practical way would be to commit with the fostering of an environment in the classroom that promotes resilience. A concrete way to understand it follows Henderson & Millstein21 Resiliency Wheel. Restorative practices are concrete means to accomplish what Henderson & Millstein21 suggest by offering high control and high support, engagement and participation and promoting prosocial behavior. An environment like this offers safety for the teachers as well: provides role boundaries, affective interactions and healthy expectations. Teachers that respond with compassionate witnessing through restorative practices done consistently will build resiliency in the learning environment and might become more resilient themselves. Restorative practices should be accessed through a compassionate witnessing lens in order to be properly implemented.

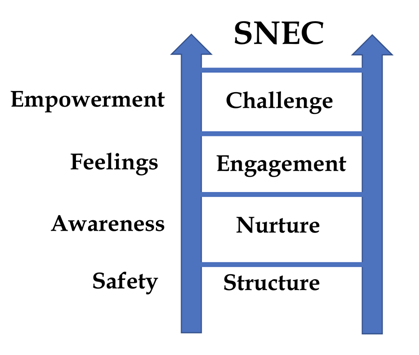

Rundell2 explains the Relational Care Ladder as a way to co-create change within traumatized children and families when intentional relational care is required. This care should escalate as follows: first of all, students need safety, from safety they can develop awareness. Awareness will let them connect with their feelings. This understanding may lead to empowerment. Rundell2 explained that the ladder encourages the following actions: safety by offering structure to the person. Awareness through nurturing. Expression of feelings through engagement and, finally, empowerment by challenging the person. She used the acronym SNEC (Structure, Nurture, Engagement and Challenge) (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Relational care ladder. Adapted from Rundell F.1

As stated before, the best quality of learning in Costa Rican high schools took place in situations where interactions where healthy and safe.3 The Relational Care Ladder is applicable to a restorative model of classroom management. Rundell’s model aligns well with Pitzer & Skinner5 when they describe teachers that foster resilience. These authors explain that teachers that promote motivational resilience are structured instead of chaotic, warm instead of rejecting, and foster students’ autonomy instead of coercing action from them.5 To establish a sense of structure and boundaries contributes in a significant way to make the space safe. To open nurturing conversations fosters awareness about the student’s rights and responsibilities. To engage the learning community in a social and emotional way by incorporating feelings is a way to promote healthy affects. To empower students means challenging them to reach their full potential. That last part will be different for each one of them and to distinguish that, as teachers, is part of the work. Rojas13 insists on the importance of inclusive education by understanding that learning needs to adjust to meet students’ diversity. Diverse profiles differentiate niches for students and represent both risks and opportunities to maximize a kid’s potential.15

Teachers also need to experience structure, nurturing, engagement and challenge in order to find true meaning and self efficacy in their job. To become compassionate witnesses, as teachers, means an ongoing exercise of deep reflection and explicit practice. It requires the commitment to work with students and not for them, so that awareness and empowerment should also manifest in their personal development as much as in their professional development. Yes, the teacher’s plate of expectations is full. To learn how to compassionate witness as teacher, he or she must also be prepared to learn, grow and take proper self-care. High-risk and high-need students need to overcome several challenges. When teachers respond to the task, they are able to model the awareness and empowerment students can choose to imitate.23

Costa Rican students require of teachers with the skills necessary to promote resilience and foster a nurturing and structured environment. Costa Rica’s Ministry of Education acknowledges these needs and offers professional development to improve teachers’ abilities.3 Restorative practices represent an innovative model that focuses on positive affect while offering a structured and fair environment. Through models based on PBIS, restorative practices, and resilience focused interventions, Costa Rican teachers can continue to strengthen their ability to give students back the joy of learning, have a deep and sensitive understanding of students’ needs, and keep control and support as part of the classroom dynamics. Teachers need to be capable of separating the students from their behavior in order to foster healthy and meaningful relationships. To do this, teachers need information, tools and support. However, professional development is not enough.

Meaningful relationships between teachers and students are significant in building an environment that promotes resilience and permanence, and restorative practices are practical and realistic means for both. Community systemic efforts are needed, including public policies that acknowledge the importance of systematic supervision, support interdisciplinary teamwork and training. Self-care is also necessary. The high expectations that the educational system puts on teachers’ shoulders will have meaning only if teachers are offered the structure, nurturing, engagement and challenge to become resilient themselves.

None.

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

©2019 Mézerville. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.