eISSN: 2577-8250

Review Article Volume 4 Issue 3

School of Architecture, Syracuse University, USA

Correspondence: Joseph Godlewski, School of Architecture, Syracuse University, 201 Slocum Hall, Syracuse, NY 13244, USA, Tel (315) 443–2256

Received: May 30, 2020 | Published: June 19, 2020

Citation: Godlewski J. Drawing from the archives: notes on the Old Residency in Calabar, Nigeria. Art Human Open Acc J. 2020;4(3):93-99. DOI: 10.15406/ahoaj.2020.04.00160

The National Museum in Calabar, Nigeria is housed in a well-preserved British colonial structure known as the Government House or Old Residency. Built in 1884, the building was prefabricated by the iron manufacturer W. MacFarlane & Co. Ltd. in Glasgow, Scotland and shipped in parts to Calabar for construction in the area known as Government Hill. Extensive scholarship has focused on Calabar however the city’s architecture has been less closely analyzed. The few publications which address the city’s urban and architectural heritage often discuss the Old Residency in isolation and without the support of primary source evidence. The aim of this article is to critically examine the building and properly situate it in its historical context. With the aid of primary source documents housed in a number of archives, photographs taken at the site, drawings of the building and city, as well as insights from secondary sources, the objective of this study is to document, help visualize, and clarify the historical record about this important architectural artifact. While the building is often described in stately and heroic terms, it is best understood as an architectural experiment which failed to achieve its original aims but has nonetheless become an important site of heritage preservation in postcolonial Nigeria. Ultimately, this article argues the Old Residency is a record not of foreign architectural eminence, unchecked imperial penetration, or the spread of modern technological progress, but a contested site and register of competing and contradictory claims of the city’s past.

Keywords: colonial urbanism, architecture, prefabrication, archives, history, Calabar, Nigeria

The city of Calabar served as a busy slaving port which transitioned to a palm oil-based economy during the period of British colonial occupation in the early part of the twentieth century. In a district known as Government Hill overlooking the Calabar River is a well-preserved bungalow type building which houses the National Museum at the Old Residency (Figure 1). Seton a neatly manicured lawn in a walled compound, the two-story structure dates from the early period of British colonial administration and reveals much about the history the of the city and its many inhabitants. Built in 1884, the building was prefabricated by the iron manufacturer W. MacFarlane & Co. Ltd. in Glasgow, Scotland and shipped in parts to Calabar for construction in the area known as Government Hill.1 The building contains museum exhibits, an archeological collection of terra cottas, and an archive containing books, correspondences, and maps from the city’s past. Calabar has been written about extensively in scholarly publications, however its architecture has been less closely analyzed. Sources that discuss Calabar’s built environment often focus on formal and stylistic concerns of individual buildings in isolation. Southeastern Nigeria and Calabarhave a long history of resistance to territorial colonization and struggles with the Nigeria’s post-colonial federal government. Nonetheless, the urban fabric today bears the unmistakable imprint of colonial architectural and planning practices. Analyzing the role of the Old Residency in that endeavor and examining it beyond formal descriptions is a critical component in understanding the city’s history.

Methodologically, this article draws from three types of sources to document and make claims about the Old Residency building. First, the article examines primary source documents dating back to the colonial era located in several archives including the National Museum in Calabar itself, the National Archives in Kew, and the British Museum. Rare plans of the building and city in colonial correspondences have been redrawn using digital software. Insights from these documents are essential to move beyond a mere formal analysis of distinct architectural features and understand the building as a socio-spatial artifact and part of a larger network of colonial building and scientific experimentation. Secondly, this article examines photographs taken within and around the building during field work in Calabar to make visible issues discussed in the primary source documents and shed light on the spatial experience of the building. Lastly, this study critically examines many existing secondary sources that discuss the Old Residency or colonial architecture and urbanism more broadly. With the aid of these primary and secondary sources the objective of this study is to document, help visualize, and clarify the historical record about this important architectural artifact.

Despite its historical significance and well-preserved state, little scholarly attention has been paid to the Old Residency. A plaque at the museum describes the building’s significance as the seat of the Oil Rivers and the Niger Coast Protectorates and the Protectorate of Southern Nigeria (after 1914) of the Resident of the Old Calabar Province. Declared as national monument in 1959, it is often featured in travel guides and considered a major tourist attraction in the region. Scholarly literature that mentions the building tends to focus on formal characteristics and praise the beauty of the structure. The guidebook to the museum features an elevation drawing of the Old Residency on the cover and describes the building as “one of the finest examples early colonial architecture in Nigeria”, detailing how the walls and floors are made of Scandinavian red-pine (pitch) wood encasing wooden structural columns and angle-iron beams. It describes how the original roof was made of slate and isolated from the sun with thatch, but that later heavy-gauge corrugated zinc sheets were placed on top.2 The historians Tonye Braide and Violetta I. Ekpo add that sashed windows and shuttered wall spaces provided adequate ventilation, reduced solar thermal gain, and gave the building a “distinguished character” character like other British colonial buildings.3 Philip G. Ajekigbe points out the ground floor and verandahs were placed on a concrete slab to isolate the structure from ground moisture and insects.4 Upon completion of the building’s renovation in 1986, then Director-General of the museum Ekpo Okpo Eyo touted the building’s “architectural eminence”.5 Popular accounts similarly exalt the building’s beauty and describe the building as among the best museums in Nigeria and a “treasure”.6 What these accounts obscure, however, is the building’s complicated legacy and relationship to colonial planning, tropical science, and Nigeria’s post-colonial identity.

Some scholars begin to move beyond observations about the building’s materiality and appearance and situate it in a constellation of colonial structures that flourished at this time. For example, historian David Imbua correctly locates the production of the prefabricated structure in the longer history of imported buildings shipped to native merchants.7 And Nnimo Bassey writes, “Before being shipped down to Calabar, the building was said to have been displayed at an exhibition of colonial architecture in London.”8 While evidence of this specific claim is hard to come by, the iron products of MacFarlane and Co. were displayed in many exhibitions throughout Europe at this time.9 This discourse is valuable for providing facts and preserving the memory of the building’s history, however closer inspection of primary source documents reveals a more complex understanding of the structure. Investigating the Old Residency as part of the nineteenth century’s development of iron architecture, prefabrication, and mass production is indeed part of the narrative, however, the building was also part of the British colonial policy of establishing European reservations and a component in a larger network of structures which experimented with environmental technologies in the tropics. Aspects of the building were debated, and its environmental performance was not without shortcomings.

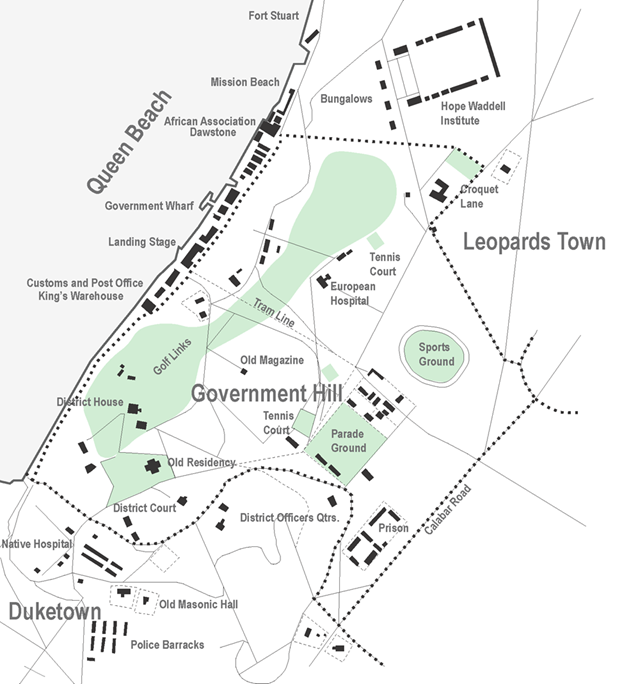

Primary source information about the Old Residency is not extensive, though a few documents from the decades after its construction are revealing. Archival photographs from the British Museum and the National archives largely confirm that the renovation of the building was stylistically consistent and true to its original form. A photograph in the British Museum taken between 1890 and 1905 shows the south facing façade and original spiral stair.10 A 1909-10 photograph shows the “Government House” surrounded by tennis courts with the Provincial Secretariat Buildings in the foreground.11 A map of the city from the National Archives in Kew situates the structure in its larger urban context (Figure 2). What the map reveals is the attempts by the British administration to establish a zone separate from the native settlements inland and to the south. Areas known as Duketown and Leopards Town were designated for native inhabitants. Modeled after Lord Frederick Lugard’s policy of indirect rule, such separation was in theory intended to prevent the spread of tropical diseases such as malaria. These areas were supposed to be separated by a wide gap or neutral zone to ensure hygienic division.

Figure 2 Diagram of Government Hill, Calabar (1911-1920). Source: Diagram by Joseph Godlewski based on National Archives, Kew, MPGG 1/129. Extracted from CO 583/87. Plan of Calabar, detail, 1911-1920.

Inspecting the plan, a significant portion of Government Hill was dedicated to what can best be described as resort-like recreational facilities. The plan of the European reservation indicated space allocated for the Old Residency along with a golf links, tennis courts, a croquet lane, and parade and sporting grounds. Recreational facilities were placed near the formal government houses, administrative offices, and police and military barracks. Consistent with the English landscape tradition, the layout of neatly trimmed lawns and verandahs were placed in a picturesque setting with winding, crisscrossing paths. A tram line cut across the reservation connecting a military installation with Queen Beach. The lived reality of this segregated urban landscape, however, was much less distinct than originally proposed. Despite concerted efforts, boundaries between factories, native settlements, and natural features intermixed. As with the attempts to spatially compartmentalize the city along race and class lines, plans to eradicate disease through segregation were difficult to implement in the administrative, economic, and geographic context of Calabar. Historian Geoffrey Nwaka points out that the kind of zoning imagined by Lugard could not be established on the ground because native settlements and European areas were already abutting each other. Attempts to legislate an order to the plan, subdividing native settlements into smaller wards were similarly frustrated.12 Boundaries in Calabar were fuzzy in practice, constantly negotiated and redrawn.13 Ayodeji Olukoju goes further, arguing the policy of urban segregation at Old Calabar was an utter “farce”.14 Archival photographs from the period show native attendants freely mixing with colonial administrators. In one image, for example, a European man playing golf in Calabar poses with his black caddy holding his clubs.15

Analysis at the scale of the building similarly reveals colonial policy undermined by the exigencies of everyday experience. In a 1907 correspondence with the colonial office on the design of bungalows for government officials in West Africa, Sir Walter Egerton describes the building at length and provides measured drawings of the building’s plans and section. Like the sources previously discussed, Egerton describes the building as, “a very good type of wood and iron house sent out from England for the High Commissioner. All of the fittings are of the very best and most expensive description; it must have cost a great deal of money.”16However, he goes on to describe many of the building’s perceived inadequacies. He continues, “It is not a comfortable house to live in. Its defects are a closed in verandah- none of the windows of which go down to the ground, there is therefore no proper ventilation to the house and the interior rooms are very dark with the result that all of the occupants live not in the in verandahs and never go into the bedrooms or dining room except for dressing and eating.”17 The bedrooms have no openings into the dining room… “The roof is badly designed and the house is like a hot house in the afternoon.”18 The re-drawn upper level plan (Figure 3) based on Egerton’s drawings shows the interior spatial organization and original functions of spaces. Viewing the plan, one can understand the frustrations he posed. While the enclosed verandahs on the upper floor provide for space for museum artifacts today, they make for a much less well-ventilated interior environment. A photograph of the building (Figure 4) shows the interior space of the upper level looking from the elaborately decorated dining room space out into the “kiosk” space and through the small shuttered windows. The smaller windows noted by Egerton do in fact make for a much darker interior experience.

Figure 3 Upper level plan of “Government House” now National Museum at the Old Residency, Calabar, Nigeria. Source: Drawing by SenaGokkus and Joseph Godlewski based on documents in CO 879/93/3: Design of Bungalows for Government Officials Etc. In West Africa, 1906-1909.

Figure 4 National Museum at the Old Residency, Calabar, Nigeria, interior view of upper level. Source: Photograph by Joseph Godlewski.

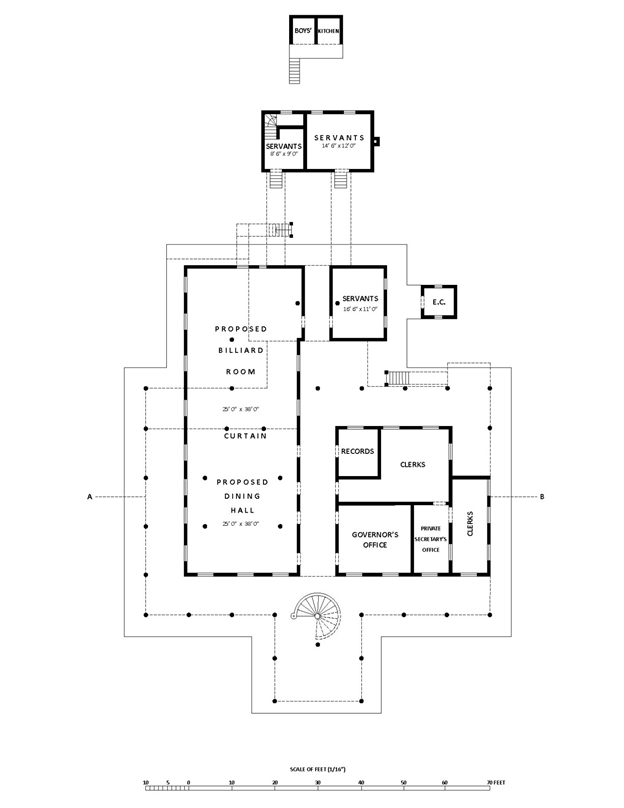

The Old Residency’s lower level plan reveals it was primarily designated for offices with servant spaces in proximity to a proposed billiards room and dining hall. A colonnaded verandah surrounds much of the lower level (Figure 5). These conditions are preserved in the present building, though the original spiral staircase placed in the center of the kiosk portion of the building has since been replaced with a straight run stair to the side. A photograph of one of one of the iron columns supporting the kiosk space shows the way MacFarlane and Co. imprinted their name on the components they produced in their Saracen foundry in Glasgow (Figure 6). MacFarlane was the most significant manufacturer of ornamental ironwork in Scotland at the time and the publication The British Architect called him the most widely known and “esteemed name in iron foundry”.19 The slender columns pictured here are covered in a bituminous coating and one of the many parts shipped throughout the empire in the nineteenth century.20 One of the purported advantages of the prefabricated set of parts developed by MacFarlane was its flexibility to be adapted to different conditions, though as Egerton described, this capacity was not always fully taken advantage of in practice. Other sources provide more evidence for the debated and unsegregated character of the building.

Figure 5 Ground level plan of “Government House” now National Museum at the Old Residency, Calabar, Nigeria. Source: Drawing by SenaGokkus and Joseph Godlewski based on documents in CO 879/93/3: Design of Bungalows for Government Officials Etc. In West Africa, 1906-1909.

Figure 6 Detail of exterior iron column, National Museum at the Old Residency, Calabar, Nigeria. Source: Photograph by Joseph Godlewski.

A1912 correspondence by sanitary officer Arthur Pickels reveals a similar uneasiness with the building but takes a different position regarding its ventilation. Pickels meticulously documented in drawing and text the environmental conditions in many colonial buildings in Calabar with a keen focus on the circulation of air and waste. He noted what he perceived as the inadequate spacing of native and European settlements and stressed the need for proper ventilation in buildings.21 Then acting Governor F.S. James, however disagreed. He wrote, “I must confess I cannot altogether agree with Dr. Pickels’s consistent recommendations as to ventilation in the quarters occupied by native staff.”22 He goes on to describe that the “craze for ventilation” had rendered houses so chilly as to make them nearly impossible to live in.23 What these correspondences demonstrate are the ways the piecemeal and experimental quality of British colonial policy in Calabar made their appearance at the scale of a building. As historian Jiat-Hwee Chang has persuasively argued in the context colonial Singapore, the British colonial state was actively experimenting with housing typologies in the tropics though they “lacked a clear vision”.24 Rather than being viewed as unadulterated symbols of colonial power, buildings like the Old Residency offer insight into the contested and uncertain nature of the imperial project.

To conclude, the National Museum at the Old Residency in Calabar, Nigeria is an important site for understanding the city’s history, but its value exceeds its physical appearance or its current function as public museum and archive. Critically examining the building and properly situating it in its historical context reveals more than its formal clarity. As Achille Mbembe writes, “The term 'archives' first refers to a building, a symbol of a public institution, which is one of the organs of a constituted state. However, by 'archives' is also understood a collection of documents - normally written documents - kept in this building. There cannot therefore be a definition of 'archives' that does not encompass both the building itself and the documents stored there.”25 When viewed together, primary source documents about the building expose a more disputatious history than its ordered edifice suggests. More than a well-preserved “monument” the Old Residency is a complicated manifestation of Britain’s involvement in the region. It is at once a success story of heritage preservation and a debatable byproduct of colonial urban policy. Considering Calabar’s long history of resistance to territorial colonization and struggles with the Nigeria’s post-colonial federal government, even the title of the “National Museum at the Old Residency on Government Hill” contains within it the contradictions of the Nigerian state. Torn between a search for post-colonial national identity, the preservation of indigenous culture, and documentation of the slave trade, the National Museum stands as an anxious site of curated knowledge. It is a record not of foreign architectural eminence, unchecked imperial penetration, or the spread of modern technological progress, but a contested site and register of competing and contradictory claims of the city’s past.

The author appreciates the insights provided by numerous reviewers of this article at various stages of its development. Barbara Opar, the School of Architecture Librarian at Syracuse University, was instrumental in finding materials for this study. The staff at the National Museum at the Old Residency in Calabar, particularly the curator Sunday Adaka, helped find materials and provided access to the building for this article. Sena Gokkus was central to the research conducted for this article, particularly in the task of redrawing archival plans of the Old Residency. This was indispensable work since obtaining rights to the original images was not possible due the COVID-19 pandemic.

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

©2020 Godlewski. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.