eISSN: 2577-8250

Review Article Volume 2 Issue 2

Lund University, Sweden

Correspondence: Xiaolin Pei, Lund University, Sweden

Received: November 28, 2017 | Published: March 21, 2018

Citation: Pei X. China’s pattern of growth and poverty reduction. Art Human Open Acc J. 2018;2(2):91–104. DOI: 10.15406/ahoaj.2018.02.00039

To escape from the poverty trap made by the law of limit to land productivity, in the early 1950s China adopted the Stalinist development strategy and transferred lots of farm surplus into state investment. This created a dual economy with investments concentrated on heavy industry and a vast surplus labor in agriculture, and in between a development gap of light industry. Around 1980, a reverse flow of farm surplus from the state to peasants tripled rural per capita income and halved rural poverty in seven years, providing funds to invest and adjust the dual economy by developing rural industry to fill the gap of light industry. It was the reverse flow of farm surplus that launched China’s economic takeoff by changing the unbalanced economy to a balanced one. This altered the per-reform structures of investment, employment and output, creating industrial jobs for the rural poor to earn higher incomes and reduce poverty. The higher industrial wages in turn provide funds to trigger “a hidden agricultural revolution” to alter the agricultural structure and further reduce poverty. So what reduces China’s poverty is industrialization-driven growth. But the World Bank researchers reverse causality and China’s history, by attributing it to sector B if sector A’s influence on poverty occurs via sector B’s output, and then claiming that what reduces China’s poverty is not industry but agriculture.

Keywords: law of limit to land productivity, poverty trap, self-adjustment of the dual economy, China’s pattern of growth, poverty reduction

According to Ravallion1 84 % of China’s population lived below the international poverty line of $1.25 per day in 1981, when only four countries, Cambodia, Burkina Faso, Mali and Uganda had a higher headcount index than China. However, The Economist (Jun 1st 2013) shows that China pulled 680 million people out of misery and reduced its extreme-poverty rate to 10% through economic growth in the years 1981-2010. Ravallion Chen,2 Montalvo Ravallion3 argue that China’s growth has been highly uneven across sectors and regions. Although the non-primary sectors are key drivers of China’s aggregate growth, the primary sector (mainly agriculture) is the main driving force in China’s poverty reduction, and it is the unevenness in sectors rather than in regions that handicaps China’s poverty reduction. Despite the unevenness in the sectoral pattern of growth, no one denies the fact that China has won the greatest success in reducing poverty in modern times, so how its pattern of growth reduces poverty has been debated heatedly. Montalvo Ravallion3 use PGH (pattern of growth hypothesis) to argue: the sectoral composition of economic activity affects the aggregate rate of poverty reduction independently of the aggregate rate of growth, meaning that the policies that are good for growth are not necessarily good for poverty reduction, because the real driving force in China’s remarkable success against poverty is not the secondary (manufacturing) and tertiary (services) sectors, but agriculture.

In contrast to the above World Bank researchers, Centre for the Study of Living Standards4 concludes: in China only higher industrial labor productivity reduces poverty. Higher agricultural labor productivity does not make any significant contribution to reducing poverty, and even make things worse. Moreover, when CSLS include the inequality variables into their regressions, results are inconsistent with the view that inequality has a significant influence on poverty. In line with the CSLS study, Zhang et al.5 use household datasets to test and show that when China has very limited farmland per head, it cannot rely on agriculture but on industrialization-driven growth to reduce poverty. This creates lots of new industrial jobs for the rural poor, and chances for them to earn higher incomes and escape from the poverty trap. Du et al.6 also use household datasets from China’s poor areas to examine whether the poor migrate and whether migration helps the poor. They find that the poor are more likely to migrate because having a migrant increase a household’s income by 8.5% to 13.1%, and migrants indeed remit a large share of their wages to satisfy the needs of their family members.

Why do the studies conflict sharply? Montalvo Ravallion3 tell us how they arrive at their conclusion: “If sector A’s influence on poverty occurs via sector B’s output, then we will attribute it to sector B. So we only identify what can be termed the proximate impacts of the sectoral pattern of growth”. It is clear that their conclusion is willfully made by cutting the various sources of interdependence among the three sectors, including externalities. For example, they do not distinguish growth in agricultural output from growth in agricultural income. The latter can result from redistribution and have little to do with the former. Moreover, Ravallion Chen2 even assume that if the same rate of growth had been possible without the sectoral imbalance, it would have taken 10 years for China to achieve the reduction in poverty over 1981-2001. As Montalvo Ravallion3 themselves admit, this type of assumption and calculation is strong in principle when China’s progress in lifting people out of extreme poverty is already rare in history. In fact, their assumption, PGH and calculation sink into absurdity. According to the law of limit to land productivity Pei,7–9 at the population trap stage growth in output of agriculture is bound to be lower than that of the secondary and tertiary sectors, so the same rate of growth across sectors is equivalent to forcing the latter to grow as slowly as the former, and China to take much longer time to reduce poverty.

To prove this, I use the economic history method to begin with things as they were, and especially China’s planned economy because economic transition, after all, is a change from one economic state to another. In contrast, most studies treat the planned economy as a hindrance to growth. So they only deal with the reform era and reach a conclusion before a full investigation. Second, I let the original statistical data speak for themselves. This not only avoids any ideological bias but also allows for unintended consequences. To make my study consistent, all the data are from the same source: China’s official statistics. This may underestimate China’s poverty Park Wang.10 But the World Bank’s poverty line and PPP measures are also criticized on the grounds that they do not anchor the line on any defined set of requirements for human life, and the PPP conversion factors are themselves problematic, based on inadequate data and an unchanging perception of consumption needs over time Ghosh.11 Third, I study rural poverty rather than urban poverty because urban poverty is new in China and mainly made by privatization of state-owned enterprises in the mid-1990s, and its headcount index is much lower than that of rural poverty. Fourth, I study the unevenness in sectors rather than in regions because Ravallion et al.1 say that it is the former that handicaps China’s poverty reduction. Fifth, almost all the studies (e.g. the Ravallion Chen,2 Montalvo Ravallion,3 Ghosh11, World Bank,12) find that much of China’s poverty reduction was concentrated in two short periods: 1979-1984 and 1995-1997. As argued above, a redistribution of the savings part of China’s pre-reform GDP (33% of GDP) raised agricultural income and created the two special periods. If growth in agricultural output per se were the key to reducing poverty, it would not only play the role in two short periods. This also refers to China’s poverty estimate which is based on income rather than expenditure data, while the World Bank stresses that the latter typically shows greater absolute poverty. But the Bank’s estimates also deny the differences among countries. The reason why under the same poverty level China can build strong heavy industry but other poor countries cannot is that China consumes less and saves more, so at the next stage it can reduce poverty faster than other countries.

To test the arguments, the next section defines the physical law of limit to land productivity, showing that this law is the origin of China’s poverty and planned system. An analysis of how the pre-reform dual economy, which was made by the planned system, induced China’s post-reform pattern of growth and poverty reduction, is presented in the third section. The fourth section introduces how the structural changes of investment, employment and output, which was caused by a self-adjustment of the dual economy in the reform era, altered the income source structure of rural households. Next is an exploration of how the decline of agricultural employment led to a hidden agricultural revolution and changed the structure of the primary sector. The last section presents conclusions.

The limit to land productivity as the origin of poverty and China’s pre-reform pattern of growth

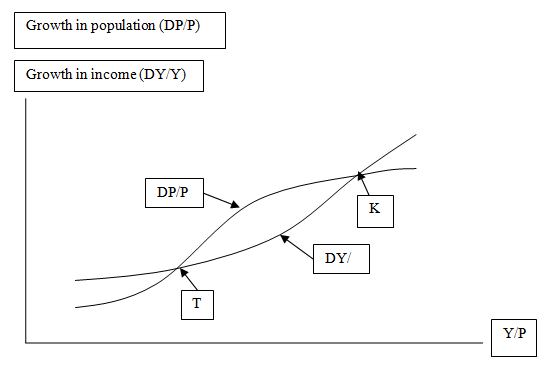

The poverty trap is in fact the Malthusian population trap. The Dictionary of Modern Economics (1983) defines this trap thus: An economy with a very low level of income per head may well find that the rate of growth of population exceeds the rate of growth of real income. If so, this is equivalent to saying that the real income per head will decline. Only where the income growth exceeds the population growth can real incomes per head actually increase. In the diagram, the rate of growth of income is greater than the rate of growth of population up to the point T, but after T the situation is reversed and incomes grow less fast than population. As such the economy moves back to point T as per capita incomes decline. Efforts to move away from T are thus doomed to failure because of the effect on population growth being more pronounced than the income growth. T is thus the ‘low level equilibrium’ or the ‘population trap’ from which the economy cannot initially escape. Only if it is possible to ‘jump’ to point K can the process of raising per capita incomes on a sustained basis be achieved.

So the Malthusian population trap (1989) can be written as AY > NS → AY = NS, or AY/N > S → AY/N = S. The area of arable land (in hectares) is A and Y the yield of grain per hectare (kg/ha); AY is the grain supply; N is number of heads; and S the subsistence level in terms of grain (kg/head). NS is the demand for grain. Malthus held that growth in N can lead a country from the stage of AY/N > S (everyone has a farm surplus) to the stage of AY/N = S (no one has a farm surplus), because A and S are constants, and N and Y are variables to growth over time, and what turns AY/N > S to AY/N = S is geometric growth in N (1, 2, 4, 8, 16 . . . every twenty-five years) vs. arithmetic growth in Y (1, 2, 3, 4, 5 . . . every twenty-five years). Put another way, the denominator increases more rapidly than the numerator. But Malthus did not answer the question of what causes Y to grow arithmetically when N grows geometrically. Hence his observation does not constitute a causal explanation but instead is a description of a phenomenon. Pei8,9 shows that by acting as a ceiling, the limit to land productivity (LTLP hereafter) checks population growth by causing Y to grow arithmetically. Malthus also did not answer the question of what causes diminishing returns; thus his view about diminishing returns is a description of a phenomenon as well. Pei8 (ibid.) illustrates that LTLP makes returns diminish and this is repeated under each level of technology; thus diminishing returns are not a law but results of the law of LTLP. Because diminishing returns mean rising labor costs per kilogram of grain, this rise is also a result of the law of LTLP. If yield per ha had no limit, farm outputs would, like industrial outputs, not correlate to land size but to labor and capital inputs, then the same amount of labor inputs in 1 ha and 100 ha would result in the same amount of outputs. There would be no diminishing returns, no poverty trap, no land conflict, and no check to population growth. In sum, if the law were different, almost all the modes of production and distribution of wealth would be other than they are.

Therefore, Pei8 (ibid.) builds a dynamic land-use model, where LTLP causes the physical, economic, and institutional systems of land use to change inversely in the three stages before, in, and after the population trap (Table 1). The starting point of China’s history of movement from the AY/N > S pre–population trap stage to the AY/N = S population trap stage is the growth in N, and the end point is LTLP. Hence growth in N led to the following results: (1) it constantly reduced land per labor; (2) it made labor inputs per ha constantly approach LTLP, because the constant A (area of arable) had to feed more people; (3) it made the contribution of natural forces per kilogram of grain fall to the bottom, and the share of manpower rise to a historical peak; (4) it made labor productivity stagnate when labor inputs per ha reach LTLP; (5) as late as 1949, it squeezed 90 percent of China’s population under the ceiling of LTLP. The only way for China to rid itself of this ceiling was to transfer agricultural labor and population to industry, thus moving rural China from AY/N = S to the AY/N > Sindustrialized stage. Therefore, reducing N and the labor force in agriculture led to the following results: (1) it allowed more and more labor and population to escape from the LTLP ceiling; (2) it expanded land per farmer; (3) it reduced labor inputs per ha; (4) it caused the contribution of natural forces per kilogram of grain to increase and the share of manpower to diminish; (5) it started to raise agricultural labor productivity and narrow the gap between agricultural and industrial labor productivity. This is why Pei13 define the essence of industrialization as freeing the growth of labor productivity from the law of LTLP. But China had not been able to industrialize by the market exchange of industrial and agricultural products, because its share of natural forces bestowed per kilogram of grain had fallen to the lowest point in China’s history and the human share had risen to its peak. So from 1953 to 1978 China used the planned system to transform the agricultural surplus value to industrial investment by the logic chain of the Stalinist strategy: the planned low price of farm products → cheap food for the urban population and cheap raw materials for state industry → low wages, low costs, and high profits of state industry → centralized fiscal revenues → high investments in heavy industry.

AY/N > S |

AY/N = S |

AY/N > S |

|

The Physical World: |

|||

A: area of arable land |

Constant |

Constant |

Constant |

N: population under the law of LTLP |

Less |

Most |

Least |

Land per rural head |

Large |

Smallest |

Largest |

The Economic World: |

|||

Land size per family farm |

Large |

Smallest |

Largest |

Labor inputs per ha |

Less |

Most |

Least |

Labor inputs to LTLP |

Far |

Closest |

Farthest |

Marginal returns to labor |

High |

Lowest |

Highest |

The average labor cost per kg grain |

Low |

Highest |

Lowest |

Labor productivity |

High |

Lowest |

Highest |

Y: land productivity |

Low |

Highest |

High |

Returns to fixed capital investment |

High |

Lowest |

Highest |

To invest in farm machines? |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Above S: surplus grain |

Have |

No |

Most |

Aim of farming |

Survival & profits |

Survival |

Mainly for profits |

The Institutional World: |

|||

Transfer of land use right |

Work |

Not work |

Work |

Land rental markets |

Work |

Fail |

Work |

Mortgaging land titles for bank loans? |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Credit markets |

Work |

Fail |

Work |

Exclusive land rights |

Not harm SNAP* |

Harm SNAP |

Not harm others |

Patterns of land rights |

More private |

More communal |

More private |

Table 1 Inverse Logics of different stages of development under the limit to land productivity (LTLP)

*SNAP, survival of newly added population

Source: Pei.8

As shown in Table 2, in the early 1950s China was a typical poor agrarian country. Its primary, secondary and tertiary sectors produced 51%, 20.9% and 28.2% of GDP respectively. The secondary sector was the weakest one, in which heavy industry was even weaker than light industry. Its output was only one third the latter’s. But under the Stalinist strategy the secondary sector rapidly grew, making its share in GDP the largest (48%) in 1978, when the shares of the primary and tertiary sectors fell to 28% and 24% respectively. The secondary sector was expanded by heavy industry because 50% of China’s investment was in it. This was 5 times the investment in agriculture and 8 to 9 times the investment in light industry, so heavy industry grew from the weakest to the strongest sector. In 1978 its share in the output structure of agriculture, light industry and heavy industry became the largest (43%), and the agricultural share dropped to 25%, while the share of light industry was always about 32% and did not grow from 1952 to 1978 Pei.14 Due to the capital-intensive nature of heavy industry that attracted lots of farm surplus into it but blocked inflow of surplus labor from agriculture, the change in labor structure lagged far behind the change in the GDP structure. From 1952 to 1978 the share of industrial labor increased only by 10%, and the share of agricultural labor decreased by 13%, while the share of service labor increased a little (3%). By contrast, from 1978 to 2012 the share of agricultural labor decreased by 37%, the shares of service labor increased by 24%, and the share of industrial labor increased by 13%, so their changing paces were 3 times, 8 times and 1.3 times their respective paces during 1952-1978. This acceleration was caused by a self-adjustment of the dual economy created by the Stalinist strategy.

Growth in three sectors of GDP |

Shares of GDP (current price) |

Shares of employment |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Primary |

Secondary |

Tertiary |

Primary |

Secondary |

Tertiary |

Primary |

Secondary |

Tertiary |

|

Preceding year=100 (constant price) |

% |

% |

% |

% |

% |

% |

|||

1952 |

101.9 |

135.8 |

124.9 |

51 |

20.9 |

28.2 |

83.5 |

7.4 |

9.1 |

1957 |

103.1 |

108 |

104.7 |

40.6 |

29.6 |

29.8 |

81.2 |

9 |

9.8 |

1962 |

104.5 |

89.2 |

90.7 |

39.7 |

31.2 |

29.1 |

82.1 |

8 |

9.9 |

1965 |

109.7 |

124.2 |

115.8 |

38.3 |

35.1 |

26.7 |

81.6 |

8.4 |

10 |

1970 |

107.7 |

134.8 |

107.1 |

35.4 |

40.3 |

24.3 |

80.8 |

10.2 |

9 |

1975 |

102 |

115.8 |

104.9 |

32.5 |

45.5 |

22 |

77.2 |

13.5 |

9.3 |

1978 |

104.1 |

115 |

113.8 |

28.2 |

47.9 |

23.9 |

70.5 |

17.3 |

12.2 |

1979 |

106.1 |

108.2 |

107.9 |

31.3 |

47.1 |

21.6 |

69.8 |

17.6 |

12.6 |

1980 |

98.5 |

113.6 |

106 |

30.2 |

48.2 |

21.6 |

68.7 |

18.2 |

13.1 |

1981 |

107 |

101.9 |

110.4 |

31.9 |

46.1 |

22 |

68.1 |

18.3 |

13.6 |

1982 |

111.5 |

105.6 |

113 |

33.4 |

44.8 |

21.8 |

68.1 |

18.4 |

13.5 |

1983 |

108.3 |

110.4 |

115.2 |

33.2 |

44.4 |

22.4 |

67.1 |

18.7 |

14.2 |

1984 |

112.9 |

114.5 |

119.3 |

32.1 |

43.1 |

24.8 |

64 |

19.9 |

16.1 |

1985 |

101.8 |

118.6 |

118.2 |

28.4 |

42.9 |

28.7 |

62.4 |

20.8 |

16.8 |

1986 |

103.3 |

110.2 |

112 |

27.1 |

43.7 |

29.1 |

60.9 |

21.9 |

17.2 |

1987 |

104.7 |

113.7 |

114.4 |

26.8 |

43.6 |

29.6 |

60 |

22.2 |

17.8 |

1988 |

102.5 |

114.5 |

113.2 |

25.7 |

43.8 |

30.5 |

59.3 |

22.4 |

18.3 |

1989 |

103.1 |

103.8 |

105.4 |

25.1 |

42.8 |

32.1 |

60.1 |

21.6 |

18.3 |

1990 |

107.3 |

103.2 |

102.3 |

27.1 |

41.3 |

31.5 |

60.1 |

21.4 |

18.5 |

1991 |

102.4 |

113.9 |

108.9 |

24.5 |

41.8 |

33.7 |

59.7 |

21.4 |

18.9 |

1992 |

104.7 |

121.2 |

112.4 |

21.8 |

43.5 |

34.8 |

58.5 |

21.7 |

19.8 |

1993 |

104.7 |

119.9 |

112.2 |

19.7 |

46.6 |

33.7 |

56.4 |

22.4 |

21.2 |

1994 |

104 |

118.4 |

111.1 |

19.9 |

46.6 |

33.6 |

54.3 |

22.7 |

23 |

1995 |

105 |

113.9 |

109.8 |

20 |

47.2 |

32.9 |

52.2 |

23 |

24.8 |

1996 |

105.1 |

112.1 |

109.4 |

19.7 |

47.5 |

32.8 |

50.5 |

23.5 |

26 |

1997 |

103.5 |

110.5 |

110.7 |

18.3 |

47.5 |

34.2 |

49.9 |

23.7 |

26.4 |

1998 |

103.5 |

108.9 |

108.4 |

17.6 |

46.2 |

36.2 |

49.8 |

23.5 |

26.7 |

1999 |

102.8 |

108.1 |

109.3 |

16.5 |

45.8 |

37.8 |

50.1 |

23 |

26.9 |

2000 |

102.4 |

109.4 |

109.7 |

15.1 |

45.9 |

39 |

50 |

22.5 |

27.5 |

2001 |

102.8 |

108.4 |

110.3 |

14.4 |

45.2 |

40.5 |

50 |

22.3 |

27.7 |

2002 |

102.9 |

109.8 |

110.4 |

13.7 |

44.8 |

41.5 |

50 |

21.4 |

28.6 |

2003 |

102.5 |

112.7 |

109.5 |

12.8 |

46 |

41.2 |

49.1 |

21.6 |

29.3 |

2004 |

106.3 |

111.1 |

110.1 |

13.4 |

46.2 |

40.4 |

46.9 |

22.5 |

30.6 |

2005 |

105.2 |

112.1 |

112.2 |

12.1 |

47.4 |

40.5 |

44.8 |

23.8 |

31.4 |

2006 |

105 |

113.4 |

114.1 |

11.1 |

47.9 |

40.9 |

42.6 |

25.2 |

32.2 |

2007 |

103.7 |

115.1 |

116 |

10.8 |

47.3 |

41.9 |

40.8 |

26.8 |

32.4 |

2008 |

105.4 |

109.9 |

110.4 |

10.7 |

47.4 |

41.8 |

39.6 |

27.2 |

33.2 |

2009 |

104.2 |

109.9 |

109.6 |

10.3 |

46.2 |

43.4 |

38.1 |

27.8 |

34.1 |

2010 |

104.3 |

112.3 |

109.8 |

10.1 |

46.7 |

43.2 |

36.7 |

28.7 |

34.6 |

2011 |

104.3 |

110.3 |

109.4 |

10 |

46.6 |

43.4 |

34.8 |

29.5 |

35.7 |

2012 |

104.5 |

107.9 |

108.1 |

10.1 |

45.3 |

44.6 |

33.6 |

30.3 |

36.1 |

Table 2 Growth and shares of GDP and employment by sector

Sources: Data of columns 2, 3 and 4 are from Table 2–4, columns 5, 6 and 7 from Table 2–2, and columns 8, 9 and 10 from Table 3–4 of China Statistical Yearbook 2013.

China’s post-reform pattern of growth and poverty reduction stems from its pre-reform dual economy

As shown in Table 3, from 1978 to 2012 China’s GDP, primary, secondary and tertiary sectors of GDP, and per capita GDP and per rural capita net income grew by 24 times, 4.6 times, 38 times, 33 times, 17 times and 12 times respectively. This reduced number of rural population living in extreme poverty from 250 million in 1978 to 27 millions in 2010. Moreover, the much higher growth rates of the secondary and tertiary sectors than that of the primary sector were bound to greatly change the structures of population and rural employment. Table 4 shows that the absolute number of the primary sector’s laborers had always increased before 1992, although its share in the rural employment structure started to fall long ago. This was because China’s huge population base and its growth not only demanded more food but also could supply more laborers to produce food. However, the absolute number of the primary sector’s laborers reached its historical peak of 391 millions in 1991 and started to fall. The average number reduced each year over 1991-2012 was 6.35 millions. The absolute numbers of rural population and rural employed persons also reached their historical peak of 860 millions in 1995 and 490 millions in 1997 respectively, and started to fall. The average number reduced each year was 12.78 million and 6.29 million respectively. Thus the rural share of population rapidly fell from 82.1% in 1978 to 47.4% in 2012. Because the absolute number of laborers of the primary sector dropped faster than that of rural employed persons, its share in the latter also quickly fell from 92.4% in 1978 to 65.1% in 2012. These changes reversed China’s 5000-years trend that when population grows but land cannot, that growth is bound to reduce land per rural head and per farmer, and make marginal returns to labor diminish, output growth lower than population growth, and income per head fixed at the subsistence level. Hence an unprecedented reduction in the absolute numbers of rural population, rural employed persons and agricultural laborers can directly increase land per rural head and per farmer, and make marginal returns to labor, labor productivity and income per rural head increase, and thus reduce rural poverty.

Gross |

Per |

Per rural |

Rural poverty |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Domestic |

Primary |

Secondary |

Tertiary |

Capita |

capita net |

population |

|

Product |

sector |

sector |

sector |

GDP |

income |

10000 persons |

|

1978 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

25000 |

1980 |

116 |

104.6 |

122.9 |

114.3 |

113 |

139 |

22000 |

1985 |

192.9 |

155.4 |

197.9 |

231.7 |

175.5 |

268.9 |

12500 |

1990 |

281.7 |

190.7 |

304.1 |

362.1 |

237.3 |

311.2 |

8500 |

1995 |

502.3 |

233.7 |

677.7 |

606.9 |

398.6 |

383.6 |

6540 |

2000 |

759.9 |

277 |

1081.8 |

956.1 |

575.5 |

483.4 |

3209 |

2005 |

1210 |

336 |

1807.9 |

1574.7 |

887.7 |

624.5 |

2365 |

2010 |

2059 |

418.9 |

3198.4 |

2767.5 |

1471.7 |

954.3 |

2688 |

2012 |

2423 |

456.6 |

3806.6 |

3272 |

1715.1 |

1176.9 |

Table 3 Indices of GDP and per rural capital net income (constant price), and number of rural poverty population

Sources: Data of columns 2-6 from China Statistical Yearbook 2013: Table 2–5; data of columns 7-8 from China Yearbook of Household Survey 2012: Table 2–3–26 and Table 2–3–40.

Population structure |

Rural employment structure |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Consumption |

Investment |

Total |

Rural |

Share |

Total |

Primary sector |

Share |

|

% |

% |

million persons |

million persons |

% |

million persons |

million persons |

% |

|

1978 |

62.1 |

38.2 |

962.59 |

790.14 |

82.1 |

306.38 |

283.18 |

92.4 |

1980 |

65.5 |

34.8 |

987.05 |

795.65 |

80.6 |

318.36 |

291.22 |

91.5 |

1985 |

66 |

38.1 |

1058.51 |

807.57 |

76.3 |

370.65 |

311.3 |

84 |

1990 |

62.5 |

34.9 |

1143.33 |

841.38 |

73.6 |

477.08 |

389.14 |

81.6 |

1991 |

62.4 |

34.8 |

1158.23 |

846.2 |

73.1 |

480.26 |

390.98 |

81.4 |

1995 |

58.1 |

40.3 |

1211.21 |

859.47 |

71 |

490.25 |

355.3 |

72.5 |

1997 |

59 |

36.7 |

1236.26 |

841.77 |

68.1 |

490.39 |

348.4 |

71 |

2000 |

62.3 |

35.3 |

1267.43 |

808.37 |

63.8 |

489.34 |

360.43 |

73.7 |

2005 |

53 |

41.5 |

1307.56 |

745.44 |

57 |

462.58 |

334.42 |

72.3 |

2010 |

48.2 |

48.1 |

1340.91 |

671.13 |

50.1 |

414.18 |

279.31 |

67.4 |

2012 |

49.5 |

47.8 |

1354.04 |

642.22 |

47.4 |

396.02 |

257.73 |

65.1 |

Table 4 Structures of GDP, population and rural employment

Source: Data of columns 2-3 from China Statistical Yearbook 2013: Table 2–18; the rest data from China Rural Statistical Yearbook 2013: Table 1–3.

These data show that China’s post-reform growth and poverty reduction indeed rely on rapid industrialization and urbanization. This pattern of industrialization stems from China’s pre-reform economy. In the early 1950s China adopted a Stalinist development strategy and raised its very low investment rate to a very high level by largely transferring farm surplus into investment in state-owned heavy industry. This created a typical dual economy with heavy industry on one side, and agriculture with its huge surplus of labor on the other, and in between a development gap of light industry. Around 1980, a rise in the state purchasing price of farm products caused the farm surplus to flow from the state to peasants. This brought both capital and investment goods to the surplus labor, inducing rapid rural industrialization to keep the pre-reform high investment rate (Tables 4) and fill the development gap caused by the underinvestment in light industry. Hence it was this reverse flow of farm surplus that launched China’s economic takeoff by changing the unbalanced economic structure to a balanced one. The essence of this reverse flow was that the pre-reform investment source (33 % of GDP) was largely redistributed by the same system that had transferred the farm surplus from peasants to the state. It shows that China started to give up the Stalinist strategy when the majority of its population was still rural, so its economic transition could begin with rapid rural industrialization.

This was possible because the dual economy could adjust itself by expanding labor-intensive light industry and service sector, which could be achieved easily by moving investment goods from heavy industry and the surplus labor from agriculture to the vacuum of light industry and the service sector. Around 1980, a reverse flow of the farm surplus from the state to peasants brought both capital and investment goods to the countryside and realized this expansion. Figure 1 shows that the long trend of the secondary sector’s share in GDP is that it rose rapidly from 20.9% to 47.9% only in the pre-reform era (1952-1978). Since 1978 it has never exceeded 47.9% except 1980, so the main trend of the GDP structure in the reform era 1978-2012 is that the share of the primary sector fell sharply from 28.2% to 10.1%. Accordingly the share of the tertiary sector rose from 23.9% to 44.6%. However, the short period 1978-1985 was an inverse trend. Both the secondary and tertiary sectors’ shares in GDP fell, from 47.9% to 42.9% and from 23.9% to 21.6% respectively. Only the primary sector’s share rose from 28.2% to 33.2%. This inverse trend clearly violated the general trend of industrialization that the primary sector’s share in GDP tends to fall, and the shares of the secondary and tertiary sectors tend to rise. It also refers to my introduction above: 1978-1985 was the fastest period when China halved rural income poverty in seven years, so the Ravallion Chen,2 Montalvo Ravallion3, World Bank,12 regard the setting up of the household responsibility system (HRS) in agriculture as the reason for this reduction and the sudden rise in income per rural head. This is why they use the two short periods, 1978-1985 and 1995-1997, as their basis to claim that only agricultural growth can reduce rural poverty.

While it is true that China reduced a half of its rural income poverty over 1978-1985, it is not true that the HRS and agricultural growth per se created the inverse trend (Figure 2). As Pei14,15 argued, this inverse trend was made by reallocating the investment share of the pre-reform GDP (33 % of GDP), because it was the reverse flow of farm surplus from the state to peasants that suddenly caused the primary sector’s share in GDP to rise, and income per rural head to grow by three times and China to reduce a half of its rural income poverty within seven years. (Tables 2)(Figure 3) show that growth in the primary sector of GDP was negative (-1.5%) in 1980 and its share in GDP fell from 31.3% in 1979 to 30.2% in 1980. However, Table 5 shows that rural net income per head grew from RMB 160.2 in 1979 to RMB 191.3 in 1980 (the nominal growth rate was 19.5% and the actual growth rate was 16.6%). Moreover, Table 5 shows that before the setting up of HRS, the number of rural poverty population had declined from 250 million in 1978 to 145 millions in 1982, so the poverty rate had dropped from 30.7% to 17.5%. By contrast, when the HRS was setting up between 1983 and 1984, the number of rural poverty population only fell from 145 million to 128 million and the poverty rate declined from 17.5% to 15.1%. These facts confirm that the reverse flow of farm surplus was not only earlier but also much more powerful than the HRS. What it reduced the absolute number and proportion of rural poverty population was six times what the HRS did.

|

P-index |

E-subsidy |

G-s-loss |

Balance |

Share |

R-income |

N-growth |

A-growth |

Poverty line |

Poverty |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

% |

billions |

billions |

billions |

% |

RMB |

% |

% |

RMB |

rate % |

1978 |

103.9 |

1.1 |

6.5 |

1.0 |

31.2 |

133.6 |

|

|

100 |

30.7 |

1979 |

122.1 |

7.9 |

-1.8 |

-17.1 |

28.4 |

160.2 |

19.9 |

19.2 |

|

|

1980 |

107.1 |

11.8 |

-6.0 |

-12.8 |

25.7 |

191.3 |

19.5 |

16.6 |

130 |

26.8 |

1981 |

105.9 |

15.9 |

-9.7 |

-2.6 |

24.2 |

223.4 |

16.8 |

15.4 |

142 |

18.5 |

1982 |

102.2 |

17.2 |

-14.3 |

-2.9 |

22.9 |

270.1 |

20.9 |

19.9 |

164 |

17.5 |

1983 |

104.4 |

19.7 |

-21.2 |

-4.4 |

23.0 |

309.8 |

14.7 |

14.2 |

179 |

16.2 |

1984 |

104.0 |

21.8 |

-19.7 |

-4.5 |

22.9 |

355.3 |

14.7 |

13.6 |

200 |

15.1 |

1985 |

108.6 |

26.2 |

-50.7 |

2.2 |

22.4 |

397.6 |

11.9 |

7.8 |

206 |

14.8 |

1986 |

106.4 |

25.7 |

-32.5 |

-7.1 |

20.8 |

423.8 |

6.6 |

3.2 |

213 |

15.5 |

1987 |

112.0 |

29.5 |

-37.6 |

-8.0 |

18.4 |

462.6 |

9.2 |

5.2 |

227 |

14.3 |

1988 |

123.0 |

31.7 |

-44.6 |

-7.9 |

15.8 |

544.9 |

17.8 |

6.4 |

236 |

11.1 |

1989 |

115.0 |

37.4 |

-59.9 |

-9.2 |

15.8 |

601.5 |

10.4 |

-1.6 |

259 |

11.6 |

1990 |

97.4 |

38.1 |

-57.9 |

-14.0 |

15.8 |

686.3 |

14.1 |

1.8 |

300 |

9.4 |

1991 |

98.0 |

37.4 |

-51.0 |

-20.3 |

14.6 |

708.6 |

3.2 |

2.0 |

304 |

10.4 |

1992 |

103.4 |

32.2 |

-44.5 |

-23.7 |

13.1 |

784.0 |

10.6 |

5.9 |

317 |

8.8 |

1993 |

113.4 |

29.9 |

-41.1 |

-19.9 |

12.6 |

921.6 |

17.6 |

3.2 |

|

|

1994 |

139.9 |

31.4 |

-36.6 |

-57.5 |

11.2 |

1221.0 |

32.5 |

5.0 |

440 |

7.7 |

1995 |

119.9 |

36.5 |

-32.8 |

-58.2 |

10.7 |

1577.7 |

29.2 |

5.3 |

530 |

7.1 |

1996 |

104.2 |

45.4 |

-33.7 |

-53.0 |

10.9 |

1926.1 |

22.1 |

9.0 |

|

|

1997 |

95.5 |

55.2 |

-36.8 |

-58.3 |

11.0 |

2090.1 |

8.5 |

4.6 |

640 |

5.4 |

1998 |

92.0 |

71.2 |

-33.3 |

-92.2 |

11.7 |

2162.0 |

3.4 |

4.3 |

635 |

4.6 |

1999 |

87.8 |

69.8 |

-29.0 |

-174.4 |

12.8 |

2210.3 |

2.2 |

3.8 |

625 |

3.7 |

2000 |

96.4 |

104.2 |

-27.9 |

-249.2 |

13.5 |

2253.4 |

1.9 |

2.1 |

625 |

3.5 |

2001 |

|

74.2 |

-30.0 |

-251.7 |

14.9 |

2366.4 |

5.0 |

4.2 |

630 |

3.2 |

2002 |

|

64.5 |

-26.0 |

-314.9 |

15.7 |

2475.6 |

4.6 |

4.8 |

627 |

3.0 |

2003 |

|

61.7 |

-22.6 |

-293.5 |

16.0 |

2622.2 |

5.9 |

4.3 |

637 |

3.1 |

2004 |

|

79.6 |

-21.8 |

-209.1 |

16.5 |

2936.4 |

12.0 |

6.8 |

668 |

2.8 |

2005 |

|

99.8 |

-19.3 |

-228.1 |

17.1 |

3254.9 |

10.8 |

6.2 |

683 |

2.5 |

2006 |

|

138.8 |

-18.0 |

-166.3 |

17.9 |

3587.0 |

10.2 |

7.4 |

693 |

2.3 |

Table 5 How the reverse flow of farm surplus from the state to peasants reduced rural poverty

I have shown the logic chain of Stalinist strategy to transform farm surplus from peasants to the state. The rise in prices of farm products immediately reversed the logic: rise in prices of farm products → food subsidies for the urban population and a rise in costs of the state sector → a huge deficit or a heavy burden on the centralized budget → getting all the provinces to share the burden and decentralization of the fiscal system → fiscal decline relative to GDP → fall of state share in total investment. At the same time, the rise in prices of farm goods created a new logical chain: rise in prices of farm products → a rise in income per rural head and peasants’ deposits → the past fiscal funds changed to bank funds → the emergence of a new investment-financing system and rural private and collective capital. Capital was invested in labor-intensive and light industries. This is how some capital originally targeted by the state for investment in heavy industry was shifted to light industry in the 1980s. This transition began with the Third Plenum of the Eleventh Congress of the Chinese Communist Party held in December 1978 when it decided to start China’s economic reform. Its first reform program was not the introduction of HRS in agriculture but to raise state-purchasing price of farm products. This policy was put into practice in March 1979. As Tables 5 shows, the rise in state-purchasing price of farm products was 22.1%, 7.1% and 5.9% in 1979, 1980 and 1981 respectively. The food price of urban consumers did not rise accordingly, because the state directed the state grain-trading system to buy dear and sell cheap. In other words, there was a rise in the purchasing price of grain but no change in urban consumer prices. State finance made up the loss suffered by the trading system. Nevertheless, the selling price of meat and eggs was going up. This was also compensated by the state budget and urban consumers directly obtained price subsidies from the state.

This policy was to stabilize urban food prices when state purchasing-prices of farm goods were rising. First, food was the biggest item in urban consumption around 1980, and food prices were the basis of China’s planned price system. If these prices got out of control, there would be runaway inflation and the planned price system would immediately collapse. Second, if the state did not buy dear and sell cheap, it had to raise urban wages and pay for the increase, because the urban sector was nearly totally owned by the state around 1980. This cost would have been greater than price subsidies if both the planned price and planned wage systems had collapsed and runaway inflation and rises in wages took place in waves, which actually happened in the East European reform.

Tables 5 shows the price subsidy suddenly jumped from RMB 1.1 billion in 1978 to RMB 7.9 billion in 1979, a seven-fold increase in one year. It then grew step by step from RMB 11.8 billion in 1980 to RMB 104.2 billion in 2000. Second, the state grain-trade system had always had large profits until 1979. The profits were RMB 6.5 billion in 1978. However, a loss of RMB 1.8 billion immediately appeared in 1979 when there was a rise in purchasing price of grain but no change in urban consumer price. The losses then rose continuously from RMB 6 billion in 1980 to RMB 60 billion in 1989. Third, the costs in the state industry that used farm products as raw materials also rose when the purchasing prices of farm goods rose, because the state did not allow industry to enjoy the policy that urban individual consumers enjoyed. Thus, this cost rose by 22.1%, 7.1% and 5.9% in 1979, 1980 and 1981 respectively, which in turn reduced industrial profits accordingly. The price subsidy, the losses in the state trading system, and the fall in profits of state industry either reduced state budgetary revenues or increased expenditures. When the state-purchasing price of farm products rose dramatically between 1978 and 1981, the revenue fell from RMB 112.1 billion to RMB 108.5 billion, but the expenditure increased from RMB 111.1 billion to RMB 127.4 billion. Thus, the budget became unbalanced. There was a favorable balance with a surplus of RMB 1 billion in 1978. Immediately a huge deficit of RMB 17.1 billion was incurred in 1979 when the state purchasing price of farm goods grew by 22.1%.

Note: P-index = overall state purchasing price index of farm products, preceding year = 100. E-subsidy = expenditure on policy related subsidies paid to consumers for the rise in prices of grain, edible oil, meat, etc. G-s-loss = government subsidies for loss-making grain-trading enterprises and commerce caused by state policy. Balance = government revenue – government expenditure. Share = government revenue/GDP. R-income = rural net income per capita (RMB, current price). N-growth = nominal growth at current price. A-growth = actual growth at constant price.

Sources: Data of P-index fromRural China Statistics Yearbook2011: (Tables 1–8) (since 2001 overall state purchasing price index of farm products has been changed to producer’s price index for farm products); E-subsidy and G-s-loss from China Statistical Yearbook 2007: (Tables 2–9) (E-subsidy and G-s-loss ended in 2006 when grain prices and purchase and sale markets were fully liberated); Balance from China Statistical Yearbook 2007: Tables 11–8 ( E-subsidies were listed as negative revenue items before 1986, but they have been adjusted and listed as expenditure items since 1986. In order to show how the rise in state purchasing price of farm products caused huge deficits from 1979 to 1985, I use the real deficit data of that period fromChina Statistical Yearbook 1990: (Tables 1–6); date of R-income, N-growth, A-growth, poverty line and poverty rate fromChina Yearbook of Household Survey 2012: (Table 3).

What is most striking is that the deficits of 1979 and 1980 (RMB 29.81 billion) were more than the deficits of the pre-reform 30 years as a whole (RMB 26.67 billion). Moreover, there were no deficits in 19 years of the pre-reform era, but there have been deficits in every year of the reform era except 1985. This became a heavy burden on China’s highly centralized budget, which forced the state to decentralize its fiscal system. On February 1, 1980, just after huge deficits were sustained at the end of 1979, the State Council issued the decentralization document. Its aim was to decentralize the fiscal burdens (getting all the local governments share expenditures on price subsidy, losses in the state trading system, etc), but revenues had to be decentralized as well. This bottom-up revenue-expenditure-sharing system encouraged local governments to generate more revenues, which indeed reduced the deficits from 1981 to 1989. But when the state purchasing prices of farm goods rose by 40% in 1994, the deficits tripled again (from RMB 20 billion to RMB 57.5 billion). Moreover, the rise in the state purchasing prices of farm goods meant the farm sector retained the farm surplus that originally had been shifted to the state budget and then invested in heavy industry. This reduced the share of budgetary revenue in GDP. As Table 5 shows, the share fell from 31.2% in 1978 to 22.4% in 1985, a fall of one-third within seven years. But note, the investment share of GDP did not fall, as shown in Table 4.

The rise in prices of farm goods per se raises rural net income per head. As Table 5 shows, the income rose from RMB 133.6 to RMB 397.6 and suddenly tripled over 1978-1985. This had little to do with inflation because before 1985 China’s inflation was very low (though it was higher after 1985). This is why the nominal and actual growths of rural net income per capita were almost the same over 1979-1985 but became different after 1985. As Qian16 shows, in 1980 the rise in prices of grain, cotton and edible oil caused incomes of peasants to increase by more than RMB 9 billion, an average of more than RMB 11 per rural head. Price rise in these three and other farm products, and other kind of price subsidies (e.g. added subsidies for over-purchase of grain and cotton) amounted to more than RMB 25 billion, equal to 25% of fiscal revenues in 1980. This is why the actual rural net income per head could grow by 16.6% in 1980 when the primary sector of GDP grew by -1.5%. According to Wang Fan17’s fieldwork, 52% of the increase in peasants’ income came from the rise in prices of farm products in the early 1980s. The rest was due to a growth in productivity made possible by the setting up of HRS.

(Table 2)(Figure 3) show that the rising trend of the primary sector’s share in GDP returned to falling trend just after the spread of HRS in rural China in 1984. The share fell from 32.1% in 1984 to 28.4% in 1985. Growth of the primary sector also rapidly fell from 12.9% in 1984 to 1.8% in 1985. Since then it has not exceeded 5% except 1990, 1995-1996 and 2004-2006. In 1990 it was 7.3% and higher than the growth in the secondary and tertiary sectors of GDP. According to Montalvo Ravallion,3 this was balanced growth across sectors and could better reduce rural poverty. But it is also Ravallion Chen2 who say that rural China’s poverty reduction stalled around 1990, recovered pace in the mid-1990s (their second short period to claim that only agricultural growth reduce rural poverty), and stalled again in the late 1990s. Table 5 clarifies the truth of the matter: the overall state purchasing price index of farm products went down from 123% in 1988 to 97.4% in 1990, and then rapidly up to 140% in 1994, and then down again to 87.8% in 1999. Therefore, the poverty rate went up from 9.4% in 1990 to 10.4% in 1991, and then quickly down to 7.1% in 1995. This was how the sudden 40 percent rise in the state purchasing price of grain caused the deficits to triple in 1994, and created the highest growth rate (32.5%) of nominal rural net income per head in the reform era. Indeed, it was the different paces of the reverse flow of farm surplus from the state to peasants that created the different growth rates of income per rural head and different paces of poverty reduction. But by attributing it to B if A’s influence on poverty occurs via B’s output, Ravallion Chen,2 and Montalvo Ravallion3 willfully confuse what the reverse flow of farm surplus did with what agricultural growth per se did.

The rise in prices of farm goods not only had the same function as the introduction of the HRS to encourage peasants to produce more, but also reversed the whole set of transfer relations of the Stalinist strategy. However, the HRS could not reverse this logical chain. This is why the rise in prices of farm goods was a more determinant factor than the HRS in launching China’s economic transition and takeoff. In sum, a three-fold increase in rural per capita income within seven years was impossible before reform, and it has not been repeated, an indication that the reverse flow of the farm surplus was a turning point in the history of People’s Republic of China. Moreover, when the reform started in 1978, 82% of China’s population was rural. When the income of 82 % of the population grew by three times and there was little change in their consumption behavior within those seven years, the income expansion provided huge investments to trigger large-scale rural industrialization. But peasants would have invested in agriculture rather than industry if the claim that agriculture is the main driving force in China’s poverty reduction had been true. The real history is that when the continued rise in state purchasing prices of farm goods pushed the share of state revenues in GDP rapidly down from 31.2% in 1978 to 22.9% in 1984, it shifted about 13% and 22% of state investments to rural collectives and private investors respectively Pei.14,15

When the redistribution ended the centralized investment system and structure, it created a pluralistic structure of state, rural collective and private investments to 65:13:22, and moved 110 million laborers from the farm to the township-village enterprises’ (TVE) sector between 1978 and 1996. What is more striking is that the reverse flow of the farm surplus could transfer 63.1 million agricultural surplus laborers to the TVE sector and cause its growth in employees and industrial output to take off and overtake that of the state sector in merely five years (1983–1988), when China had no factor market. It was this expansion that filled the structure gaps of investment, labor and industry and output created by the Stalinist strategy.8 This is why the labor structure, as Table 2 shows, quickened its change from 1982 to 1988, when the share of the primary sector decreased from 68.1% to 59.3% (8.8 percent), and the shares of the secondary and tertiary sectors increased from 18.4% to 22.4% (4 percent) and from 13.5% to 18.3% (4.8 percent) respectively. By contrast, from 1978 to 1982 the shares of the secondary and tertiary sectors only increased by 1.1 percent (from 17.3% to 18.4%) and 1.3 percent (from 12.2% to 13.5%) respectively, and the share of the primary sector decreased by 2.4 percent (from 70.5% to 68.1%).

However, the reverse flow of farm surplus cannot automatically transform into investments. There must be heavy industry that can quickly provide rural collective and private investors large amounts of capital goods. This is precisely what China’s strong heavy industry, which was built in the pre-reform era, did in the reform era. This is also why the sharp fiscal decline relative to GDP did not lead to investment decline relative to GDP. If heavy industry had still been the bottleneck sector of the early 1950s, the redistribution of the savings part of GDP in the early 1980s would surely have led to a rapid investment decline relative to GDP, and the above structural changes of investment, labor and output would not have taken place. This is why China’s pattern of growth and poverty reduction was a product of its pre-reform dual economy.

How the structural changes of investment, labor and output alter the income source structure of rural households

As shown in table 6, the income of rural households comes from wages, household operation, property and transfer. Note that the wages income was from agriculture before 1983 because the wages came from the income distribution of collective farms, but from the secondary and tertiary sectors in 1983 when land was all equally distributed to households and the HRS replaced collective farming. Second, agricultural income of household operations already existed in the collective farming era when a small part of land was family plots. Third, the household operation has three income sources: the primary, secondary and tertiary sectors. Hence in the last column of Table 6, the income share of the primary sector over 1978-1982 was the income share of wages plus the income share of household operation; after that it was the income share of household operation times the income share of the primary sector.

|

Structure of income sources (%) |

Income composition of household operation (%) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Wages |

Househod |

Property |

Transfer |

Primary |

Secondary |

Tertiary |

Share of primary |

|

income |

operation |

income |

Income |

sector |

sector |

sector |

sector |

1978 |

66.1 |

26.8 |

|

7.1 |

94.4 |

|

5.6 |

92.9 |

1979 |

62.9 |

27.5 |

|

9.7 |

90.8 |

|

9.2 |

90.4 |

1980 |

55.6 |

32.7 |

|

11.7 |

90.0 |

|

10.0 |

88.3 |

1981 |

50.9 |

37.8 |

|

11.2 |

84.9 |

|

15.1 |

88.7 |

1982 |

52.9 |

38.1 |

|

9.1 |

77.9 |

9.7 |

12.4 |

91.0 |

1983 |

18.6 |

73.5 |

|

7.9 |

93.4 |

1.8 |

4.8 |

68.6 |

1984 |

18.7 |

73.6 |

|

7.6 |

92.4 |

1.8 |

5.7 |

68.0 |

1985 |

18.1 |

74.4 |

|

7.4 |

89.1 |

3.2 |

7.6 |

66.3 |

1986 |

19.3 |

73.9 |

|

6.8 |

88.6 |

3.8 |

7.6 |

65.5 |

1987 |

20.6 |

74.7 |

|

4.7 |

87.1 |

4.5 |

8.4 |

65.1 |

1988 |

21.6 |

74.0 |

|

4.4 |

85.7 |

5.0 |

9.2 |

63.4 |

1989 |

22.7 |

72.2 |

|

5.1 |

85.5 |

5.1 |

9.4 |

61.7 |

1990 |

20.2 |

75.6 |

|

4.2 |

87.9 |

4.1 |

7.9 |

66.5 |

1991 |

21.4 |

73.9 |

|

4.7 |

88.0 |

3.9 |

8.1 |

65.0 |

1992 |

23.5 |

71.6 |

|

4.9 |

86.7 |

4.3 |

9.0 |

62.1 |

1993 |

21.1 |

73.6 |

0.8 |

4.5 |

83.6 |

3.9 |

12.6 |

61.5 |

1994 |

21.5 |

72.2 |

2.3 |

3.9 |

84.7 |

4.1 |

11.2 |

61.2 |

1995 |

22.4 |

71.4 |

2.6 |

3.6 |

85.0 |

4.3 |

10.8 |

60.7 |

1996 |

23.4 |

70.7 |

2.2 |

3.6 |

84.2 |

4.7 |

11.1 |

59.5 |

1997 |

24.6 |

70.5 |

1.1 |

3.8 |

82.8 |

5.3 |

11.9 |

58.4 |

1998 |

26.5 |

67.8 |

1.4 |

4.3 |

81.3 |

5.5 |

13.2 |

55.1 |

1999 |

28.5 |

65.5 |

1.4 |

4.5 |

78.6 |

6.3 |

15.1 |

51.5 |

2000 |

31.2 |

63.3 |

2.0 |

3.5 |

76.4 |

7.0 |

16.6 |

48.4 |

2001 |

32.6 |

61.7 |

2.0 |

3.7 |

77.2 |

6.9 |

16.0 |

47.6 |

2002 |

33.9 |

60.0 |

2.0 |

4.0 |

76.4 |

7.3 |

16.3 |

45.8 |

2003 |

35.0 |

58.8 |

2.5 |

3.7 |

77.6 |

7.0 |

15.4 |

45.6 |

2004 |

34.0 |

59.5 |

2.6 |

3.9 |

80.1 |

6.2 |

13.7 |

47.7 |

2005 |

36.1 |

56.7 |

2.7 |

4.5 |

79.7 |

5.9 |

14.5 |

45.2 |

2006 |

38.3 |

53.8 |

2.8 |

5.0 |

78.8 |

6.3 |

14.9 |

42.4 |

2007 |

38.6 |

53.0 |

3.1 |

5.4 |

79.6 |

6.3 |

14.2 |

42.2 |

2008 |

38.9 |

51.2 |

3.1 |

6.8 |

79.9 |

6.1 |

14.0 |

40.9 |

2009 |

40.0 |

49.0 |

3.2 |

7.7 |

78.7 |

6.5 |

14.8 |

38.6 |

2010 |

41.1 |

47.9 |

3.4 |

7.7 |

78.8 |

6.4 |

14.8 |

37.7 |

2011 |

42.5 |

46.2 |

3.3 |

8.1 |

78.2 |

6.0 |

15.8 |

36.1 |

Table 6 Composition of sources of per capital annual net income of rural households (%)

Source: Data of columns 2, 3, 4 and 5 are from Table 2–3–20, and columns 6, 7 and 8 from Table 2–3–25 of China Yearbook of Household Survey 2012.

This share fell from 93% in 1978 to 36% in 2011 when the primary sector was no longer the main source of per capita net income of rural households. This great transition started from 1983 when millions of surplus laborers shifted from the farm to the TVE sector, so 18.6% of household income came from the wages of rural collective industry and the income share of the primary sector fell from 91% in 1982 to 68.6% in 1983. Moreover, because TVEs include collective-owned township and village enterprises, as well as individual household enterprises and partnerships, in the substructure of household operation 9.7% and 12.4% of income in 1982 already came from the secondary and tertiary sectors respectively. The former includes industry and construction. The latter includes transportation, shops, restaurants, etc. run by families. From 1978 to 1985 this structural change largely reduced rural poverty by extending the income source from the primary to the secondary and tertiary sectors, because the income from the latter is much higher than that from the former. This is why when the farm surplus was returned to peasants, they did not invest it in agriculture but in industry.

In the long run, this transition has three stages with different paces. From 1983 to 1989 the share of wages income rose from 18.6% to 22.7% when the collective-owned TVEs developed most rapidly, and in the substructure of household operation the income shares of the secondary and tertiary sectors also rose from 1.8% and 4.8% to 5.1% and 9.4% respectively, so the income share of the primary sector and the poverty rate Table 5 fell together, from 68.6% and 16.2% to 61.7% and 11.6% respectively. Between 1990 and 1995 the change slowed down and the share of wages income could not exceed 22.7% except 1992, when Deng Xiaoping gave a speech in south China in order to change the dismal situation after the Tiananmen Square crackdown. This did not change rural China much because the crackdown had less influence there, but it changed the urban situation and led to a new high tide of urban economic growth. As Figure 3 shows, the growth rates of the secondary and tertiary sectors jumped from 3.2% and 2.3% in 1990 to 21.2% and 12.4% in 1992 respectively. This drew 62 million rural surplus laborers to cities and work there, and formed a migrant trend which caused the share of wages income of rural households (23.5% in 1992) to exceed the 1989 level. But around 1995 many urban state-owned enterprises were privatized, which caused high urban unemployment and slowdown of the migrant trend. However, Table 4 shows that the absolute number of the primary sector’s laborers reached its historical peak of 391 millions in 1991 and started to fall in 1992. The absolute numbers of rural population and rural employed persons also reached their historical peak of 860 millions in 1995 and 490 millions in 1997 and started to fall in 1996 and 1998 respectively. All these historical turns were caused by the migrant trend. Moreover, the trend recovered around 2000, making the share of wages income (31.2%) much higher than the 1989 level. From 2000 to 2011 the trend speeded up and increased about 8 million migrants each year. Around 2005 the number of migrant workers reached 120 million and accounted for 24% of the rural labor force, even more than that of local employed TVE workers. Thus the share of wages income increased to 42.5% in 2011. This plus the share of transfer income (8.1%) in 2011, which was also mainly from remittance of migrant workers, far exceeded the income share of household operation (46.2%), and hence played a key role in reducing rural poverty by reducing the income share of the primary sector to only 36% in 2011.

As Ghosh11 concludes, China has followed the classic industrialization pattern, moving from primary to manufacturing activities. The manufacturing sector has doubled its share of the workforce and tripled its share of output, so the Chinese growth pattern reduce rural poverty by generating more productive and remunerative employment and making the share of agriculture in output and employment down together. But in India the share of agriculture in employment continues to be more than 60 percent, indicating a worrying persistence of low productivity employment for most of the labor force. This difference occurred because China’s investment rate has been 35 to 45 percent and much higher than India’s, and the decisive investment in infrastructure has averaged 19 percent of GDP in China compared to 2 percent in India. As I argued, all these differences stem from China’s heavy industry built in the pre-reform era. Without its strong productive capacity, China cannot keep the high investment rate and provide infrastructure with large amounts of investment goods. However, Ravallion,1 Montalvo Ravallion3 argue that in India the service sector is the more powerful force in reducing poverty. But Table 6 shows that China does not differ from India at the household level: in the substructure of household operation the income share of the tertiary sector over 1982-2011 was at least twice that of the secondary sector, and more powerful in reducing poverty by reducing the income share of the primary sector. What differs is that the Chinese State (including both the central and local governments) is harder than that of India in allocating resources.

How the decline of agricultural employment alters the structure of the primary sector

According to Huang,18 there has been an ongoing “hidden agricultural revolution” in China. As seen in Table 7, from 1978 to 2012 the gross output value of the primary sector grew by 7 times within 34 years, much higher than growth in the 18th century English agricultural revolution and the “green revolution” of the 1960s and 1970s. Huang terms it “hidden agricultural revolution” because the classic revolution depended on raising the yield of certain crops, but the hidden revolution depends on changing low-value farm products to high-value products. The gross output value of animal husbandry and fishery grew by 14 times and 22 times respectively, while the gross output values of farming and forestry only grew by 4.8 times and 6 times respectively. By producing high value products, animal husbandry and fishery made greater contribution than farming and forestry to the 7 times growth of the gross output value of the primary sector.19 This is why their shares in the gross output value of the primary sector grew from 15% and 1.6% in 1978 to 30.4% and 9.7% in 2012 respectively, while the share of farming sharply fell from 80% to 52.5% and the share of forestry had little change. Moreover, Table 8 shows that what caused the output value of farming to grow by 4.8 times is also a change from low-value farm products to high-value products. This is via a structural change in sown acreage, where the shares of vegetable and fruit increased from 4.8% and 3.5% in 1990 to 13.3% and 7.2% in 2010 respectively, so the share of grain decreased from 76.5% to 55.9%.20 The output values per sown unit of vegetable and fruit is at least 3 times that of grain. In 2010 for example, grain only generated 15.2% of output value of the primary sector, less than one-third of its proportion (55.9%) of sown acreage, while the shares of output values of vegetables and fruits were more than their shares in sown acreage. Thus in 2010 the output values of vegetables already exceeded that of grain. If we put the shares of output values of vegetables (18.8%), fruits (7.9%), animal husbandry (30%) and fishery (9.3%) together, they account for 66% of output values of the primary sector.21,22 This is why Huang outlines the hidden revolution as a change of the Chinese diet of grains, vegetables, and meat from the past ratio of 8:1:1 to a new ratio of 4:3:3. From the demand side, this upgrade of food structure is drawn by the rising income per head from the high growth of China’s non-farm sectors, which lays a foundation for buying high-value food.23–26

Indices of gross output value (1978=100) |

Structure of gross output value (%) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Total |

Farming |

Forestry |

Animal husbandry |

Fishery |

Farming |

Forestry |

Animal husbandry |

Fishery |

|

1978 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

80 |

3.4 |

15 |

1.6 |

1980 |

109.1 |

106.4 |

113.7 |

122.6 |

103.9 |

75.6 |

4.2 |

18.4 |

1.7 |

1985 |

161.6 |

152.2 |

176.2 |

203.4 |

185.1 |

69.3 |

5.2 |

22.1 |

3.5 |

1990 |

203.9 |

186.5 |

179.5 |

282 |

346.7 |

64.7 |

4.3 |

25.7 |

5.4 |

1995 |

291.9 |

230.1 |

257.7 |

495.4 |

730.3 |

58.4 |

3.5 |

29.7 |

8.4 |

2000 |

391.5 |

287.6 |

314.7 |

724.5 |

1152.9 |

55.7 |

3.8 |

29.7 |

10.9 |

2005 |

505.5 |

351 |

380 |

1012.2 |

1510.8 |

49.7 |

3.6 |

33.7 |

10.2 |

2010 |

639.3 |

435.2 |

529.1 |

1278.4 |

1983.9 |

53.3 |

3.7 |

30 |

9.3 |

2012 |

700.6 |

479.7 |

607.5 |

1368.5 |

2179.4 |

52.5 |

3.9 |

30.4 |

9.7 |

Table 7 Gross output value of farming, forestry, animal husbandry and fishery

Source: Statistical Survey of China 2013 (Excel version), Part 9: Agriculture, Industry and Energy. Data of indices are calculated at constant prices, while data of structure are calculated at current prices. Since 2003, gross output value includes the services in support of agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry and fishery. Their data are not shown here.

From the supply side, the structural change of the primary sector is caused by opportunities for rural laborers to work in the secondary and tertiary sectors and earn higher income than that of the primary sector. When the higher income causes laborers to shift from the primary to the secondary and tertiary sectors, it changes the land/labor ratio from the past situation where labor is more relative to land to a new situation where labor becomes less relative to land. Thus the price of labor is no longer set by diminishing returns on farming but by the high returns on industry and service labor. This alters the structure of the primary sector from producing low value goods to producing high value goods, in order to make returns on labor closer to that on industry and service labor. Because China’s arable land is in shortest supply and only 2 mu per rural head (15 mu = 1 ha), this structural change also leads to more efficient land use. As seen in the case of vegetable, land productivity is raised by tripling the output value per mu of the past level. But the structural change needs investment when family farms replace labor with capital. This is also solved by the higher income of secondary and tertiary sectors. The migrant workers are young and male laborers and the busy season needs their hands. But the income from hand planting-plowing-harvesting is much lower than the wages of off-farm work, so they do not go home but remit their wages, then their families can buy tractors or hire in tractor to plant, plow and harvest. This is how the wages of migrant workers provide the investment of the structural change, and why today in rural China’s most areas, plowing, planting, harvest and transportation of harvest are no longer done by hands but by tractors and motor vehicles.

As shown in (Table 6)(Table 8), the property income emerged in 1993 when the migrant trend was just formed, and the property was mainly tractors and motor vehicles, and the income was from hiring out them. So the three sources of rural households’ income, wages, property and transfer are all rooted in the secondary and tertiary sectors. Moreover, (Table 7)(Table 8) show that from 1990 to 1995, the number of small tractors was almost doubled and increased more rapidly than other periods, the output values of animal husbandry and fishery grew by 176% and 211% respectively and faster than other periods, the share of grain in sown acreage dropped more sharply than other periods, and the share of fruits in sown acreage increased faster than other periods. Only the share of vegetables in sown acreage extended fastest between 1995 and 2000. Hence the hidden agricultural revolution stemmed from the migrant trend formed from 1990 to 2000. If there had been no opportunity to work in the secondary and tertiary sectors and earn higher income than that from farming, the revolution would not have taken place. This revolution, which can reduce rural poverty by raising agricultural productivity, is a result of industrialization-driven growth.

Motor |

Big-medium |

Small |

Grain sown |

Output |

Vegetable |

Output |

Fruit sown |

Output |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

vehicles |

tractors |

tractors |

acreage % |

value % |

sown acreage % |

value % |

acreage % |

value % |

|

1990 |

0.28 |

0.45 |

5.3 |

76.5* |

31.4* |

4.8 |

n.a. |

3.5 |

n.a. |

1995 |

0.51 |

0.77 |

9.93 |

59.6 |

26.1 |

7.1 |

n.a. |

5.4 |

n.a. |

2000 |

1.32 |

1.41 |

16.72 |

54.6 |

17.4 |

11.3 |

14.4 |

5.7 |

4.2 |

2010 |

2.4 |

3.36 |

19.45 |

55.9 |

15.2 |

13.3 |

18.8 |

7.2 |

7.9 |

Table 8 Numbers of major productive fixed assets per 100 rural households and the relative proportions of sown acreage and output value of major farm products

*They are the “all food crops” figures, including potatoes and beans.

Source: Data of columns 2-4 from China Statistical Yearbook 2013: Table 13-11; the rest data from Rural China Statistical Yearbook 2002, 2012: Table 6–14, Table 2–7 and Table 30.

Compared with other developing countries, China’s most distinctive feature of the past sixty-five years as a whole has been the very high and stable investment rate, around 33 percent from 1953 to 1990 and as high as 40 percent from 1991 to 1995. The Stalinist strategy created this high rate, as well as tensions and an imbalance between the state-owned heavy industry and the vast surplus labor of the collective farm sector. Around 1980, when the rise in prices of farm goods ended the strategy’s forced accumulation policy, these tensions were released and sustained the high level of investment. China’s vast surplus labor naturally demanded investment in the vacuum of light industry, which created off-farm jobs. To reduce its overproduction, heavy industry automatically supplied investment goods for the expansion of light industry. From the demand side the dire shortage of consumer goods also drove the expansion of labor-intensive and light industries and absorbed their products. This self-adjustment of the dual economy even led to higher rates of investment when it launched China’s economic takeoff.

The farm surplus connected China’s vast surplus of labor and heavy industry, so it was its reverse flow that launched China’s economic transition and takeoff. From 1979 to 1985 when the continued rise in state purchasing prices of farm goods tripled rural per capita income, a half of income poverty rapidly vanished. What further raised income and reduced poverty in the second half of the 1980s was that the farm surplus was not consumed but invested, and it was not invested in agriculture but in rural industry (TVEs), so the sources of employment and rural per capita income were quickly expanded and varied. Moreover, the higher investment rate of the 1990s led to a high urban economic growth in the secondary and tertiary sectors. This absorbed millions of rural surplus laborers, creating a trend of migrant workers and more off-farm jobs and sources of rural per capita income. The wages of migrant workers then became the source of investment to launch the hidden agricultural revolution and speed up poverty reduction. These changes followed one after the other, making a sound circle of growth and poverty reduction.

But by attributing it to sector B when sector A’s influence on poverty occurs via sector B’s output, Ravallion et al.1 conclude that the driving force in China’s remarkable success against poverty is not the secondary and tertiary sectors but agriculture. Their ideological bias also cause them to see China’s pre-reform economy as a hindrance to growth, only deal with the reform period and cut its historical relation to the first stage. This method reaches a conclusion before a full investigation. Moreover, Ravallion2 defies the disparity between China and other poor countries by saying that 84 % of China’s population lived below the international poverty line of $ 1.25 per day in 1981, when only Cambodia, Burkina Faso, Mali and Uganda had a higher headcount index than China. In fact, China’s high poverty rate was made by the planned accumulation system and differs from that of other poor countries with market systems. This is why China’s dual economy with a vacuum of light industry, a dire shortage of consumer goods, a huge rural surplus labor force, a strong heavy industry, and a rise in prices of farm goods naturally triggered its economic takeoff and reduced a half of income poverty within seven years. Using Figure 1, we can say that by the high savings and investment rate (33% of the GDP), China jumped to point K on the eve of its economic reform, and redistributing the savings induced the process of raising per capita incomes on a sustained basis. But without the high savings rate, other poor countries cannot move away from point T.