eISSN: 2577-8250

Review Article Volume 3 Issue 4

Department of Psychopedagogy, University of Costa Rica, Costa Rica

Correspondence: , Tel +50687022841

Received: June 22, 2019 | Published: July 10, 2019

Citation: Mézerville C. Adolescence and creativity: cognitions and affect involved in positive youth development. Art Human Open Acc J. 2019;3(4):163-168. DOI: 10.15406/ahoaj.2019.03.00125

This paper explores creativity as a necessary skill for education in the adolescent years. Adolescence is explored as a life stage where the brain is sensitive to social interaction and responds best to conditions that incorporate neuroeducational principles, as described by Campos,1 and explored through pedagogical practices. Creativity, understood as the process of generating new ideas that have value, is analysed as a skill that manifests not only in the arts and music, but also in other subjects such as math, history and science. Moreover, it is explored as a way for adolescents to become engaged with society as active participants in their community. How to encourage this in the school setting is explored through Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs,2 through an attitudinal and behavioural model of Self Esteem,3 through healthy relational interactions at school based on emotional intelligence,4‒6 positive attachment,7 and through compassionate witnessing.8 Creativity is a skill for self-fulfillment and positive engagement in society. It requires school settings and committed adults to foster positive youth development and to encourage teens to become engaged, to create and to thrive.

Keywords: creativity, adolescence, emotional intelligence, self-esteem, education, neuroeducation.

Adolescence is the stage in human development when the social brain is especially sensitive towards acceptance or rejection.9 According to Espinosa,10 this life stage is key in the building of the person’s identity and exploring the personal skills for relationships and constructing a life plan. Adolescence is a life stage when engaged participation in education is absolutely indispensable for the individual to find his or her place as an active member of society. Educational environments should systematically promote that youth gets involved in social and emotional environments that foster resilience, warmth, structure and autonomy,11 as well as high control and high support.12 This paper defends that creativity, understood as the process of having original ideas that have value,13 is an essential component for adolescent’s personal development and it can be fostered through the creation of environments that stimulate both cognitive abilities and affective maturity.

Adolescence is a life-stage where the individual experiments with autonomy and builds his or her own identity as an emerging adult. According to the World Health Organization, it is the stage that takes place after childhood and prior to adulthood, between 10 and 19 years of age.14 During adolescence, the person needs to separate herself from the identity interiorized since childhood, become exposed to new relational environments, and rebuild a sense of self.10 This developmental period of change, with its related crisis, is actually part of the healthy psychological process necessary to create a satisfying relationship with the person’s self, the person’s intimate relationships and the person’s life plan.

This life stage has been associated with many different things: a transition between childhood and adulthood, a developmental crisis, a life-stage full of risks, a stage associated with rebellion and behavioural problems.9,15‒17 This is a life stage when the human brain is especially sensitive to social interaction with peers; participating actively in groups offers adolescence better life satisfaction and positive affect.18 The reward drive in the adolescent brain is algo going through a sensitive period of development. According to Siegel,19 the natural consequences of increased reward drive manifest through (1) impulsiveness, (2) susceptibility to addiction related with the release of dopamine, and (3) Hyperrationality, understood as how adolescents place more weight on the calculated benefit of an action than on the potential risks of that action.19 To consider adolescence as a stage associated with risk, rebellion and conflict responds to adult centered prejudices15,17 that consider teen years as a period that must be endured and survived to acquire maturity. However, the adolescent brain, with its particular structure, actually represents opportunities for learning, building relationships and becoming engaged in community participation.This life period as ideal for embracing positive goals and acknowledging adolescents’ intuition as something to be assessed critically but not to be feared.16,20 These assessment is crucial as part of developing a life project, which, as a cognitive process, also stimulate the frontal cortex.20 and elicits empathy through the exercise of self-awareness.21 Adolescence is the stage to deal with these manifestations to develop personal and emotional skills, such as insight, empathy and integration.

As it has been stated before, the psychological tasks of adolescence involves the separation of the childhood self, becoming exposed to relational environments and rebuilding one’s identity.10 During this process, cognitive skills must be stimulated and strengthened. Neuroscience as a field offers a guidance that can be integrated into the educational systems and dynamics.1 According to Campos, neuroeducation is defined as research and practical actions “to make knowledge about the brain and the process of learning accessible to educators”.1 This author describes how adolescent brains follow twelve principles when it comes to education:

Based on these twelve principles1 is important to consider how teachers and educational systems respond, in order to ensure learning and healthy cognitive development. Relevant aspects on this matter are described in the following Table (Table 1).

Neuroeducational principles1 |

Implications for educators and practitioners towards adolescent students |

It is capable of learning and teaching itself. |

Encouraging engagement and gradually fostering autonomy through the development of self-leadership and self-efficacy.22 |

Learning is a human and natural process. Appropriate learning “feels normal.” |

Professional Development regarding pedagogical mediation based on Vigotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development.23 |

The brain learns through consistent patterns. |

Structure in education is necessary regarding boundaries, consistency in the learning process and healthy role models from the adults. |

Emotions nuance functional learning. |

Significant learning takes place through the emotional processes of interest and excitement.24 |

The brain needs the body and vice versa. |

Nutrition and physical activity are an intrinsic part of the healthy cognitive development. |

Different brains learn through diverse means and methodologies. |

To incorporate Multiple Intelligence as part of the pedagogical mediation will foster an inclusive classroom.25 |

Different brains learn through different styles. |

Different styles do not only mean visual, auditive, or kinesthetic. Learning styles include styles such as conceptual, reflexive, impulsive and analytic.1 Engaging learning takes place through a rich and varied methodology. |

The brain is vulnerable to genetic and environmental influences. |

Brain is sensitive to deprivatory situations that include but are not limited to personal unsafety, nutritional deprivation, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), substance abuse, among others. A deprived brain not only has important learning barriers,26 but it is also reactive, impulsive, and prompt to respond defensively. |

Music and art are associated with high brain functioning. |

The centers of the brain related with these activities will foster more fluent neural connections that stimulate healthy and active cognitive development. |

The brain is intrinsically related to information processing and memory functioning. |

Memoristic learning limited to consuming information in the working memory for temporary periods of time 25 does not work. However memory stimulation through exercises related with processing information, strengthen the cognitive routes necessary for learning. |

Sleep and rest are essential for proper brain functioning. |

Research shows that silence is necessary for neurogenesis (creation of new brain cells).27 The modern world is highly over-stimulating. Social and economical conditions of many teens expose them to continual noise. For teachers and counselors to advise healthy sleeping habits, and to foster silence periods of time within the school environment is necessary. |

The brain establishes different routes for attention and motivation. |

The cognitive routes for attention and motivation that students are creating might not be the ones that teachers expect. Continual feedback loops between teachers and students 1 will ensure that attention and motivation work properly in the relational teaching dynamic. |

Table 1

By the author.

According to Robinson,13 creativity consists on having original ideas that have value. Adolescence, as a life stage, is still flexible and plastic regarding the managing of new information,9,20 the reward drive that could represent risk, also represents a sensitivity for engagement towards goals that have personal or social value.20 Although every adolescent is different, with an intrinsic personality, external social and economical variables, personal history, and belief systems, this life stage puts teens in a position where they have elements in common regarding their natural processes of biological development and the societal dynamics through which adults interact with adolescents in educational systems. For schools, the topic of creativity in education is often related with pedagogical mediation to involve music and arts in the processes of learning. This is very relevant, given that, as stated before, music and arts stimulate high-brain-functioning, and processes of inclusive learning must involve diverse teaching styles and approaches.1 However, to circumscribe creativity to the field of music and arts is a mistake. Creative thinking can be applied to science, math, language and history. Creativity, by definition, is the creation of original ideas. The fields of music and arts make it more plausible to include creative thinking, but original ideas can also become incorporated in other fields. It is necessary for education to consider creative thinking as part of the learning curriculum in fields that are not traditionally associated with it. Education will continue a traditional, adult-centered and vertical direction,15 unless creativity is seriously considered as a significant element for subjects that are not related with arts and music. A humanistic approach to education that fosters creativity must include a sense of awareness, empowerment, collaborative learning and active participation towards school subjects that have individual and collective implications.

A first step towards incorporating creativity as a transversal axis for educational dynamics with teens is to contemplate the needs involved in a learning community. Maslow2 developed a theory of human motivation that introduced a hierarchy of human needs (Figure 1). Although creativity is plausible in unsafe and extreme circumstances, often triggered by a survival mode, creativity as an educational approach will only work as long as the person’s physiological, safety and social needs are met. Children and youth are unable to learn if they feel threatened.19 For creativity and learning to occur, educational environments must be safe, socially healthy and estimulating for the individuals.

Figure 1 Maslow hierarchy of needs; adapted from Maslow A.2 a theory of human motivation.

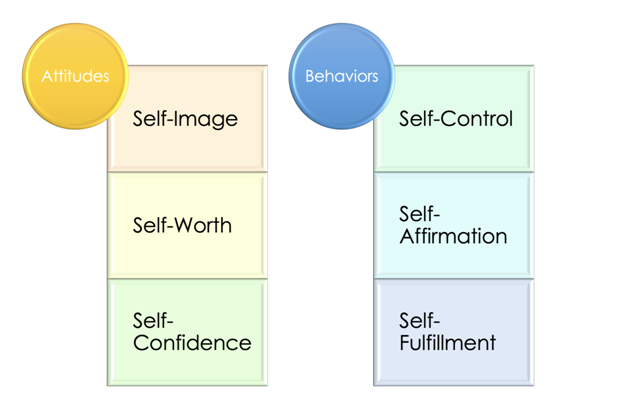

It is relevant to refer to the Self Esteem Need, and how it is a key component in the learning process. Popularised as a self-help concept, Self-Esteem is often defined as loving one self. However, this definition becomes vague and difficult to operationalize. Having a healthy and strong sense of self has to do with internal and external psychological dynamics that are fundamental for learning, especially in the teenage years. According to De Mezerville,3 self esteem is based on attitudinal and behavioral skills. Self Esteem is based on three key attitudes: (1) Objective self image; (2) Intrinsic self worth, and (3) Self Confidence. Self Esteem is manifested in three behavioural settings: (1) Self control; (2) Self affirmation, and (3) Self Fulfillment (Figure 2).

Figure 2 A model for self esteem: attitudes and behaviors. Adapted from De Mezerville.3

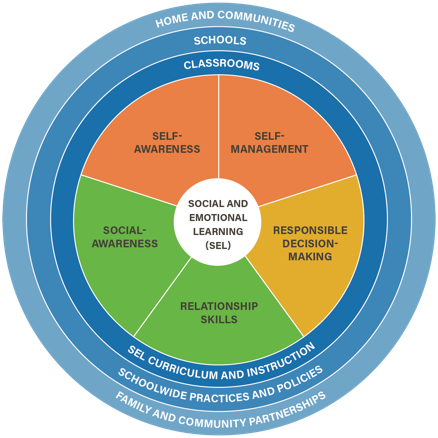

A student with a positive and objective self-image is capable to acknowledge his strengths and weaknesses without falling in unhealthy dynamics of shame.24 The attitude of self-worth relate with the fundamental sense of deserving respect. Self-confidence has to do with recognizing that the person is capable to face different challenges. Regarding the behaviors, the model emphasizes self-control as the capacity to manage one’s own life with order, according to the person’s belief system. Self-affirmation refers to the capacity to say what the person feels and thinks in an assertive way. Finally, Self-Fulfillment refers to Maslow’s understanding of finding one’s own contribution to life and society through self satisfying accomplishments.3 This refers back to the Hierarchy of Needs.2 The Hierarchy of Needs has been approached in education through strategies related with Social and Emotional Learning (SEL). SEL is an emerging field in education that emphasizes the importance of self awareness, self management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision making (Figure 3).28

Figure 3 Social and emotional learning (SEL); retrieved from CASEL.28

This framework responds to the safety, social, personal and self- fulfillment needs presented by Maslow2 for students to thrive. Social and Emotional Learning as a response to human needs for creativity can be better understood through the analysis of emotional intelligence.

Emotional Intelligence is a concept that has been popularized since the middle of the nineteen nineties. It has even been said that skills related with emotional intelligence are more important than academic or intellectual abilities, and Emotional Intelligence has become part of the common language. In 1995, Goleman published his book Emotional Intelligence, to describe what it means to give intelligence to human emotion. Goleman5 developed his discoveries on the emotional architecture of the brain, as well as the intervention of neurological factors related with the basic talent for Emotional Intelligence. Some of the abilities that he mentioned include: refraining from emotional impulses, interpreting one’s and other people’s feelings, and handle interpersonal relationships appropriately. Although Goleman5 popularised the concept, Emotional Intelligence was discussed ever since 1990. Salovey & Mayer defined Emotional Intelligence as the expression, regulation and conscious management of one’s own emotions.4 These authors mention how people that don’t learn how to handle their own emotions become enslaved by them. Bar-On6 takes the subject further developing a model for an Emotional Coefficient, which he defines as the knowledge necessary regarding Emotional Intelligence to face daily life. According to Bar-On,6 the Emotional Coefficient is constructed with five elements:

For creativity to take place in the learning environment, students must learn to become self aware and responsible for themselves. This is a life stage where they are getting acquainted with their own emotional reactivity from a different standpoint, compared to when they were children. Developing emotional intelligence in the teenage years is a positive investment in the building of a healthy identity for their present self and for their future adult-self. Adolescents also need to learn how to handle stress, adapt to change and deal positively with interpersonal relationships.6 During adolescence, most individuals are in the process of developing maturity on these skills, whether consciously or unconsciously. It is normal to expect that teens haven’t mastered these skills yet. Self leadership, as described by Bandura22 involves developing the skills for self-regulation and constructing a sense of self-efficacy, which is absolutely necessary for a healthy Self-Esteem: it responds to self-confidence, self-control, and self-fulfillment as described by De Mezerville.3 Many adults haven’t mastered these personal skills. What should be the expectation of adolescents within educational settings? The answer is not to dismiss these skills as hard, but to foster and encourage them. It must be kept in mind that, by nature, this is a social process. Intergenerational relationships with positive adult models are required for these abilities to grow.29

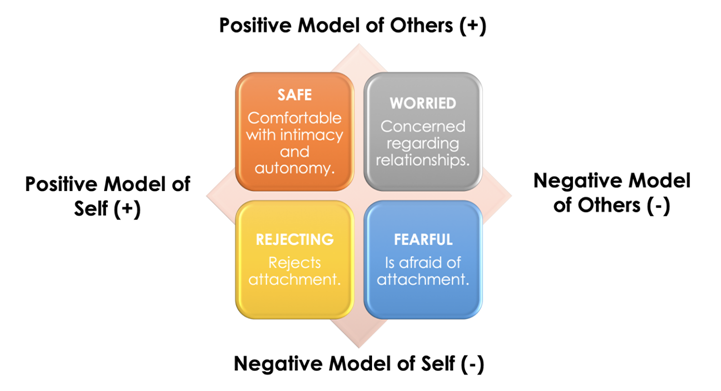

Kennedy & Kennedy30 have studied how attachment deficiencies in the person’s infant primary bonding experiences, can reflect on conflictive relationships with teachers further in life. Bartholomew & Horowitz7 model for types of attachments is very illustrative of how this can manifest in young adults’ interactions (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Attachment types according to the model of self and others. Adapted from Bartholomew & Horowitz .7

Positive Youth Development (PYD), understood as the dynamic processes that foster healthy human development, subjective well being, adaptive behaviors and positive outcomes in adolescents and emerging adults. For PYD to take place, Allen et al.31 affirm that teachers can foster PYD through: (1) an authoritative teaching approach; (2) trusting relationships; (3) building respect, and (4) generating a safe school environment.31 Positive relationships with adults are fundamental to build a learning community that encourages learning. The necessary setting for adolescent learning is not only based on students developing Emotional Intelligence as an individual skill, but on building a community of learning with consistent interactions that structure, engage, challenge and empower youth.32 A context like this will encourage even the timid or deprived students to create original ideas that have value. To build a safe relational environment will require for adults to represent safe and positive role models for students,31 to offer warmth, structure and encourage autonomy1 and to model recovery strategies towards positive affect and emotional intelligence.24 Through this process of nurture, engagement and challenge, the social and emotional learning process has a strong positive outlet: creativity. Positive SEL will encourage students to create in order to respond to the learning community and to attain a psychological sense of Self-Fulfillment.2

Weingarten8 talks about compassionate witnessing as a way to respond transformatively to violence. Violence can manifest in personal interactions, it can be functional, expressive, transgenerational or structural. As the author says, “When whole groups are humiliated and must swallow their resentment, the desire for revenge builds (…) When one generation fails to restore social and political equality, this failure forms the next generation’s legacy”.8 Compassionate witnessing is based on awareness and empowerment. Engaging adolescents as active members of education and society15,17 requires for the educational setting to encourage compassionate witnessing. To incorporate creativity in education means to acknowledge that youth has ideas that are valuable, not only for the sake of their own learning, but to respond to society’s key issues.

Creativity should not be limited to pedagogical methodology, nor to techniques to incorporate arts and music in the classroom. These actions are important and should be done. However, creativity in schools should be understood as offering a protagonic role to the student body in the process of learning. This can only happen if the learning environment is aware and responsible of the human needs of all its members: needs for health, safety, social -respectful and kind interactions-, fostering strong self-esteem, and encouraging self-fulfillment.2 A healthy relational environment will assist adolescents on the interactions that respond to a positive sense of themselves and others,7 in order to develop appropriate emotional intelligence4,5 and a healthy emotional coefficient.6 Social and Emotional Learning offer practical approaches for practitioners to build such an environment. Still, creativity should not be considered only for the sake of learning a specific subject or to cover academic curriculum. Creativity in education has to do with strengthening the cognitions and affects that will foster PYD so that adolescents become engaged with the social reality in their communities:

(...) If we don’t give children time to learn about how to be with others, to connect, to deal with conflict, and to negotiate complex social hierarchies, those areas of their brains will be underdeveloped. As Hrdy states: “One of the things we know about empathy is that the potential is expressed only under certain rearing conditions.” If you don’t provide these conditions through a caring, vibrant social network, it won’t fully emerge.33

Creativity is the birthplace of commitment, co-responsibility and joy: it builds self-esteem, it engages the person with whom he or she is, and with the reality that he or she wants to respond to in a transformative way. Education and creativity need to work hand in hand to foster a neuroeducation with cultural and social sensitivity. Collaborative learning and engaged participation through emotional intelligence are key elements for this process. As adults, teachers, parents, youth leaders, and school administrators, the task at hand is to engage adolescents to become the best version of themselves and to respond to the uncertainty of the twenty first century with commitment, passion, and responsibility.34

To foster creativity in adolescents within school settings, the following recommendations are considered especially relevant:

None.

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

©2019 Mézerville. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.