eISSN: 2577-8250

Short Communication Volume 1 Issue 4

1Multidisciplinary Institute of History and Human Sciences-National Council of Scientific and Technical Research, Argentina

2Multidisciplinary Institute of History and Human Sciences-National Council of Scientific and Technical Research, University of Buenos Aires, Argentina

Correspondence: Maria Cecilia Pallo, Multidisciplinary Institute of History and Human Sciences-National Council of Scientific and Technical Research, Argentina

Received: October 24, 2017 | Published: December 21, 2017

Citation: Pallo MC, Borrazzo K. The archaeology of contact in southern patagonia: some issues to be resolved in the southwestern forest. Art Human Open Acc J. 2017;1(4):135-138. DOI: 10.15406/ahoaj.2017.01.00023

The use of new raw materials, particularly glass, stoneware and metal, for manufacturing traditional indigenous weapons has been so far one of the main lines of evidence of the archaeology of contact in mainland southern Patagonia (southernmost South America). Here, a new finding for the southwestern forest in Argentina is presented. This information is useful to discuss chronology, different strategies of European material procurement (direct or indirect) among local indigenous populations, and the role of the southwestern forest in native land use patterns during the contact period.

Keywords: archaeology of contact, European raw materials, southern Patagonia, forest land use patterns

The use of glass as lithic raw material for traditional technological forms is recorded in several aboriginal archaeological contexts from South America,1-5 United States,6-8 India,9 Africa10 and Oceania,11-14 among others. These flaked artifacts are commonly associated with contact encounters during European colonial expansion7,11,14-18 and they are described as remanufactured glass.19 According to Martindale & Jukavik,2,19 two of the issues addressable in the analysis of indigenous remanufactured glass artifacts are:

The archaeology of contact in mainland southern Patagonia, the southernmost region of both Argentina and Chile, still has a lot to say about the significant changes in the history and life ways of indigenous populations caused by the European colonization of the Americas. The incorporation of new raw materials, particularly glass, stoneware and metal, into the manufacture of traditional indigenous weapons has been so far one of the main ways of exploring these changes.20-32

These exotic materials were obtained by local indigenous groups, highly mobile hunter-gatherers (although they were less and less mobile with the advance of the European colonization)33, through a wide variety of contact situations with Europeans,34,35 after the Spanish arrival at the southern Atlantic coast of Patagonia in 1520.36 The current spatial distribution of archaeological remains on mainland southern Patagonia indicates that most of the artifacts manufactured on these new raw materials, especially glass, are recorded in archaeological sites located on the eastern steppes, and to a lesser extent within the western mountain forests or the transition zone between forest and steppe (Figure 1). This paper presents new data from an archaeological site located in southwestern Patagonian forest, which allow addressing questions about the contact period within this environment that remain unanswered.

Figure 1 Southern mainland Patagonia: distribution of European materials recorded from archaeological sites of hunter-gatherers.

The Southwestern forest in mainland southern Patagonia

Explorers who travelled along mainland Patagonia during the XIX century and the early XX century mentioned the limited use of the southwestern forest by historical indigenous groups, ethnographically known as “Aónikenk” or “Tehuelches meridionales”.37 Their chronicles note the mobility and settlement patterns of local groups led by the “caciques” Mulato38 & Blanco,39 and the exploitation of forest fruits when resources were scarce among the natives.40 The boundary between forest and steppe also appears to have been a key pathway for mobility on horseback between the southern coast and the inland.29,40-43

Despite the historical sources, a first archaeological survey of the area recorded scattered findings in the transition zone between forest and steppe, but no artifact were registered in the fores.44 Subsequent studies resumed surveying in the "empty zone", redefining an archaeological scenario of sporadic but repeated occupations by hunter-gatherers.20,37,45-47 Among the latter a new surface open air site, named Ea. La Escondida was added (Figure 1). The site is located high on a hill (ca. 300mts), on the east margin of the Guillermo river valley. This stretch of the Guillermo River is set within the current transition zone between forest and steppe, although it should have been part of the forest until recently.48

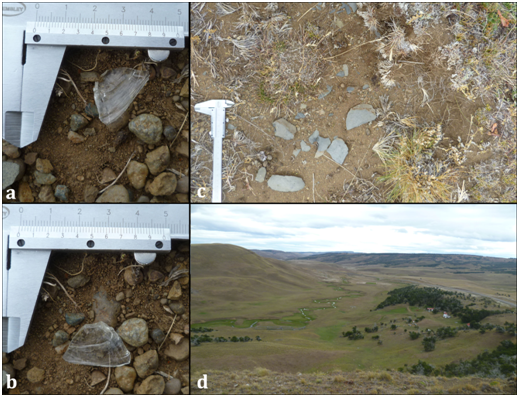

Ea. La Escondida site records a lithic assemblage, represented by 54 small flakes on locally available shale, and one flake on clear glass (Figure 2). It is worth mentioning that no other glass artifacts or European materials were recorded at the site nor in the neighbor area. The glass flake (1.9 x 2.3 x 2 mm) is too small to allow a reliable identification of the object from which it was obtained. However, several technological and taphonomic traits on this single finding allow further discussion. The flake is thin, flat and wide and exhibits a small parallel flaking scar on the dorsal face, indicating the use of a single percussion (pressure) platform. Platform angle is >120° which jointly with the thin, flat and wide shape of the flake and the diffused bulb of percussion agree with (bifacial?) thinning process, probably by pressure. Similar technological attributes were exhibited by the shale flakes, which in turn emphasize the common technological background of local hunter gatherers. As for the study of taphonomic traits on the glass flake, it allowed to detect a remnant surface (platform and adjacent edge on dorsal face) that shows differential weathering (mainly abrasion) suggesting differential subaerial exposition times. That is to say that the flake from Ea. La Escondida was detached from a piece of glass which had been previously exposed to weathering/erosion processes for some time (deposited in a rubbish dump of a European ranch?). Taking technological and taphonomic data together, Ea. La Escondida finding suggests that an indirect provisioning strategy for glass (i.e. gathering from a rubbish dump, collected on the coast, see below) cannot be ruled out.

Figure 2 Ea. La Escondida site: (a) Dorsal and (b) ventral faces of the glass flake; (c) lithic assemblage on locally available shale; (d) location and view to the Guillermo river valley.

A likely chronology for the archaeological context could be the incorporation of these spaces into the political economy of Capitalism, occurred with the advance of the sheep farming frontier between 1900 and 1922 AD.49 However, to find out how European raw material was obtained by local hunter-gatherers is also required. Either, direct interactions with Europeans or situations that did not require direct confrontation could be involved in the acquisition of these materials by the natives.34,35 Indirect contacts refer mainly to the numerous shipwrecks occurred in the Patagonian coasts during the XVII century.50 The impact of shipwrecks in the availability of raw material in southern Patagonia could implicate an early chronology for the procurement of European materials among the natives, even prior to the beginning of the European settlement of the region (since the end of the XIX century)49.35,51,52

A final issue to be solved is the role of this forest area in the land use patterns of hunter-gatherers during the contact period. In particular, if this sector was used by displaced indigenous groups and/or natives seeking to avoid contact with colonizers who were inhabiting European settlements in favored lands53-57 or it became a place adequate for interactions, given that, once European materials were incorporated into the life ways of indigenous groups, the increasing availability of European settlements would have made the procurement of this materials easier and predictable.22,35 Until now, the co-occurrence towards the end of the XIX century and the early XX century of a high use of glass in the manufacture of indigenous weapons and the early creation of farming sites and small villages supports this idea for mainland southern Patagonia.58 Nevertheless, the taphonomic trends recorded on the finding of Ea. La Escondida suggests that an indirect provisioning strategy (involving scavenging and reclamation processes) is an feasible alternative for glass procurement in southwestern forest environment of mainland Patagonia.

The archaeology of contact shows heterogeneous and contrasting spatial contexts for traditional indigenous weapons manufactured with European raw materials among different areas of southern Patagonia. These differences area explained as a result of a number of key factors interacting with one another to varying extents in the mainland.32 This is, the introduction of the horse as a resource exploited in many ways by native people since the XVIII century,59,60 the integration of commercial networks based on local resources such as guanaco (Lama guanicoe, the main prey of indigenous groups) into a newly imposed political economy of Capitalism, changes in original home range sizes, settlement and demographic patterns of mobile hunter-gatherers,53-57,61-63 as well as the establishment of European settlements, sheep farms and indigenous reserves since the XIX century.49

New archaeological data presented here begin to glimpse advances in the information available for the southern western forest in mainland southern Patagonia. These findings are still few, but they already point out that the previously boundary established for the spatial distribution of historical indigenous populations44 needs to be revised.45 This information also posits specific key aspects that need to be addressed by the archeology of contact: how much further into the western forest will traditional indigenous artifacts manufactured on European raw materials could be recorded?, what forms of European raw material procurement (direct or indirect) among local indigenous populations were involved?, and what role did the southwestern forest play into the land use patterns of historical hunter-gatherers settled in mainland southern Patagonia? Finally, data presented here is a new contribution to approaches on hunter-gatherer populations within the context of historical culture-contact dynamics, since the use of European raw materials to manufacture traditional weapons is often identified on a wide variety of archaeological sites around the world.1-35

We thank the editor and anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments, which helped us to improve the manuscript. We also thank Luis A Borrero for their support and help. This research was supported by CONICET and ANPCyT (PICT2014-2061).

The author declares no conflict of interest.

©2017 Pallo, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.