eISSN: 2576-4500

Review Article Volume 6 Issue 2

Industrial Engineering Post-Graduate Program, Nove de Julho University, Brazil

Correspondence: Henrricco Nieves Pujol Tucci, Industrial Engineering Post-Graduate Program, Nove de Julho University, São Paulo, Brazil

Received: May 02, 2022 | Published: July 7, 2022

Citation: Tucci HNP, Neto GCO. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on airline ground operations. Aeron Aero Open Access J. 2022;6(2):75-81. DOI: 10.15406/aaoaj.2022.06.00143

The SARS-COV-2 pandemic changed the routines of all companies during 2020. While some had their sales boosted, most had losses, resorted to loans, cancelled contracts, fired many employees, or even needed to shut down their activities. It is unanimous to affirm that the airlines were highly affected by the pandemic due to the closure of the borders between countries to prevent the spread of the virus. Thus, this work aimed to analyze the effects of the new coronavirus pandemic on airlines, specifically on their activities and operational employees. To this end, interviews were conducted to get an overview of 12 different airlines operating in Brazil, the impacts of COVID-19 and the application of combat practices recommended by the World Health Organization were analyzed, under the eyes of specialists in Occupational Health and Safety (OHS). The results indicated the need for airlines to reduce the size of the aircraft fleet, cancel service contracts, and carry out mass layoffs. In addition, the use of masks, social distancing and staggering of shift schedules were effective to reduce risks of contagion. On the other hand, the engagement of managers and training programs was considered fundamental for the proper implementation of these actions.

Keywords: airline, covid-19, flight mechanics, occupational health and safety, coronavirus prevention protocols

The SARS-COV-2 pandemic has broken the borders of continents and resulted in economic and social impacts on a global level.1 It can be said that the airlines were perhaps the most affected companies by the pandemic, as the current business model requires the constant operation to keep cash on hand.2 Remembering that plane on the ground is a detriment to airlines. As for the employees, those who are directly related to flight operations, were more affected by the reduction of working hours or layoffs.3

The World Health Organization (WHO) is frequently publishing guidelines on how to combat COVID-19, including helping companies overcome the challenges of maintaining their activities with a focus on employee health and safety. In the meantime, scientific articles confirming or contesting actions to face the pandemic are being published.4 In turn in aviation, knowledge is recognized as important,5 in addition, it is essential to transmit health and safety values to passengers, especially in pandemic times.6

It is worth emphasizing that the aviation sector is used to economical adversities in its operations, such as the high price of oil barrel that affects the price of aviation kerosene, terrorist attacks that impact on stricter security measures, global economic crises and international conflicts that reduce the number of passengers and limit access to touristic destinations.7 But none seemed to destabilize the airline industry as much as the new corona virus pandemic.8

Global airline connections play an important role in the dissemination of SARS-COV-2.9 Thus, governments around the world have closed their air borders and, consequently, have established international travel prohibitions as a preventive measure to avoid the collapse in national health systems.10 On the other hand, airlines are vital to transport hospital supplies and medicine,11 such as vaccines for COVID-19.12

Airlines invest and disclose to passengers how safe it is to fly, even during the pandemic.6 For example, aircraft can have HEPA filters that can filter 99.97% of the air in 3 minutes.13 Like what happens with the flight shame movement, the lack of knowledge affects the behavior of future passengers resulting in reduced demand.14 However, no studies have been identified in the literature that investigated the practices of combating COVID-19 in the ground activities of aircraft, as well as the impacts caused in this sensitive and important sector within the airlines.

Vaccination in Brazil is advancing rapidly, but the death toll is high, new variants still cause many deaths, such as Delta,15 Mu in Colombia16 and Lambda in Peru.17 More recent, the Omicron variant has spread rapidly around the world and makes it difficult to predict the end of the spread of the disease.18 In addition, Brazilian scientists are currently investigating the proliferation of the Darwin variant of the Influenza virus, and there are already cases of patients like Flurona, the combination of these two updated diseases. On the other hand, and more critically, there is a trivialization of protocols to combat COVID-19, even after almost 2 years of pandemic, such as companies providing their employees with masks made of cardboard.

Thus, the following research question has been developed: Is the pandemic of the new coronavirus causing impacts and changing processes in airlines, more specifically, in employees who work with aircraft operational activities? Therefore, this work aims to analyze the effects of the pandemic of the new coronavirus on the operational activities of the aircraft (Figure 1).

This work was first developed by presenting a brief contextualization of the SARS-COV-2 pandemic and its connection with airlines. Subsequently, a review of the literature that deepened the investigations of these themes and presented the practices to combat COVID-19 recommended by the WHO. Then, the conceptual model was developed, and after that, the methods adopted for data collection and analysis were presented. The next section consisted of the results obtained and the discussion of literature. The last section was the conclusion of this work highlighting the contributions achieved.

The relation between COVID-19 and civil aviation (CCA)

Airlines that have developed their business models supported by a strategy known as low-cost low fare, commonly characterized by regional services, standardized aircraft fleet, and paid on-board service, can face these uncertain times due to the pandemic than the other airlines, since they have in their organizational cultures the focus on reducing operational costs.3

Even so, the results of all airlines around the world were strongly affected by the new coronavirus (CCA-01), especially companies located in Western countries. Thus, it was observed the need to establish public policies with immediate implementations to reduce the damage caused by the shortage of demand.19

It is worth mentioning that large companies in the airline industry appealed to governments where their headquarters and factories were installed seeking economic support in exchange for repatriation of values and mitigation of the risks of large-scale layoffs. This scenario occurred in European countries,20 as well as in the United States of America21 and South Korea.22

However, almost all traditional and large airlines had to lay off employees without an estimated period of return or had to carry out their resignations.23 Once it was necessary to fire employees to survive the crisis imposed by the pandemic, the airlines decided to dismiss the less skilled employees and outsourced (CCA-02) to mitigate the risks of losing business expertise.3,8

A relevant component in this equation is the politicization of airlines since many of them now have the government among its majority shareholders. In this way, business models may be changed, to preserve future jobs (CCA-03) if the pandemic continues.24

In addition, airlines play a vital role in mitigating pandemic outbreaks, such that in 2006 the Collaborative Arrangement for the Prevention and Management of Public Health Events in Civil Aviation (CAPSCA) was created to organize the airline industry to facilitate international collaboration and cooperation between companies. It is important to mention the participation of CAPSCA in the dissemination of practices to combat covid-19 established by the WHO.11

Additionally, aviation has been responsible for transporting and distributing the vaccines against COVID-19 (CCA-04). This transport method was chosen due to the fast delivery and because it is already prepared to carry materials that require special care, such as temperature control.12

Moreover, aviation safety has consolidated standards focused on knowledge and redundancy, professionals in the aerospace sector are aware of the importance of their health conditions (CCA-05) to perform their functions.5 However, no studies were identified that investigated the relationship between COVID-19 and the airlines operational activities. Thus, five relevant aspects were identified (Table 1) concerning the impacts of the new coronavirus pandemic on airlines.

|

Code |

Description |

Ref. |

|

CCA-01 |

The airline where I work needed to cut costs due to the new coronavirus pandemic. |

|

|

CCA-02 |

The airline I work for had to shut down outsourced employees due to the new coronavirus pandemic. |

|

|

CCA-03 |

The airline I work for had to fire employees because of the new coronavirus pandemic. |

|

|

CCA-04 |

The airline I work for is transporting supplies, medicines, or vaccines due to the new coronavirus pandemic. |

Dube et al.12 |

|

CCA-05 |

The airline I work for is concerned with the physical and mental conditions of all employees who put their hands on the plane. |

Grout and Leggat5 |

Table 1 Impacts of the new corona virus pandemic on airlines

Practices to combat COVID-19 (PCC) in the industry

Since the beginning of the new coronavirus pandemic, the WHO has remained active in its announcements recommending practices to combat COVID-19, including considering various work activities.25 Hand hygiene was considered important to avoid contagion between people (PCC-01), thus, company employees must have adequate access to perform hand washing with soap and water or in lack of these, alcohol 70%.4 In addition, body temperature should be measured at the beginning of each shift for all employees, by means of laser or flash thermometers, which allow measuring at a safe distance.26

The provision of personal protective equipment (PPE) (PCC-02), especially face masks or respirators type N95 or FFP2,27 allow the protection of the respiratory system, the main route of dissemination of the new coronavirus.6 The correct use of PPE depends on mapping to identify the correct type of equipment according to the risks exposed. In addition to campaigns to raise awareness, on the other hand, contribute to convey a sense of security for employees to perform their most concentrated activities.28

Social distancing (PCC-03) through the arrangement or redesign of workstations is important to combat COVID-19,27 it can be accomplished by limiting the number of people in enclosed spaces1 or by creating scales to avoid agglomerations in the designated period for meals.26 It is important to highlight that the adoption of social distancing is considered feasible even by companies that are facing financial problems since it is possible to be done without investments.28

Workforce distribution over shifts (PCC-04) to reduce employee concentrations in only one working period helps combat COVID-19.28 The staggering of working hours aims to avoid the contact of employees of different shifts (1); thus, isolation bubbles are created to protect all employees by reducing the risks of cross-contagion.26

Disinfection of tools, surfaces, and workplaces (PCC-05), in combination to a frequent and standardized execution, helps to reduce the risk of contagion by the new coronavirus.4,28 Dedicating efforts to ensure that all environments can be assisted with fresh and well-ventilated air.1,26,27 Continuous monitoring of COVID-19 symptoms in employees, as well as control to identify infected but asymptomatic employees, allows companies to refer these employees to specialized hospital centers (PCC-06),28 This action reduces the risks of spreading the virus inside the company and to the relatives of employees. In addition, it is of great importance that companies immediately communicate the relevant health authorities with detailed information of infected employees.26 However, only the study conducted by Sotomayor-Castillo et al.,6 linked COVID-19 combating practices to airline operations, however, the work focused its efforts on investigating the feelings of protection of passengers inside aircraft. Therefore, 06 COVID-19 combating practices were identified in industries (Table 2).

|

Code |

Description |

Ref. |

|

PCC-01 |

The airline where I work recognizes the importance of hand hygiene and body temperature control. |

|

|

PCC-02 |

The airline where I work provides personal protective equipment, including masks. |

Michaels and Wagner;27 O’Neill;28 Sotomayor-Castillo et al.;6 Spinazzè et al.4 |

|

PCC-03 |

The airline where I work promotes social distance. |

Garzillo et al.;26 Michaels and Wagner;27 O’Neill;28 Parker1 |

|

PCC-04 |

The airline where I work strives to avoid contact by employees on different shifts. |

|

|

PCC-05 |

The airline where I work promotes the disinfection of tools, surfaces, and workplaces. |

Garzillo et al.;26 Michaels and Wagner;27 O’Neill;28 Parker;1 Spinazzè et al.4 |

|

PCC-06 |

The airline where I work conducts suspicious cases to hospitals. |

Table 2 Practices to combat COVID-19

Conceptual model

Thus, this work aims to evaluate the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on airline ground operations, as well as to evaluate covid-19 combating practices to preserve airline ground operations employees. For this purpose, the following conceptual model (Figure 2) was developed.

Methods, data collection and analysis procedures

The problem definition and the adopted strategy to answer the research questions raised is the first step in the research methods29 the method chosen was a multiple case study carried out through interviews and document analysis. It is important to mention that due to the new coronavirus pandemic, it was not possible to make face-to-face visits to the chosen companies. Even so, this paper can be classified as an exploratory and descriptive research because it intends to identify the different ways in which the problem manifests itself, while considering different points of view.30 Data collection was carried out through semi-structured interviews with employees of 12 different airlines. In addition, company documents obtained from social networks and provided by employees during interviews were analyzed. Due to the new coronavirus pandemic, all interviews were conducted remotely, through virtual meetings.

The three-step procedure that made the interviews possible was supported by Karlsson and Yin.31 The planning of the interview stage (i) was carried out by combining the findings identified in the literature review, combined to the experience of two experts, with long years of experience in the Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) processes and airline ground operations. Thus, it was possible to perform the pilot tests of the interview and supporting documents. Although the experts did not participate in the interviews, the data analysis stage was largely supported by their participation. All notes resulting from the interviews were discussed with these experts to ensure a complete and correct understanding of the information collected. The data collection (ii) was initiated by sending a descriptive document about the research objectives and an overview of the work, as well as the scheduling of interviews. In this document it was also described that the anonymity of the participants and companies would be guaranteed, in addition to that, no interview was recorded, and the notes of the researchers were shared with each respondent to ensure the transparency and ethics of the protocol. A descriptive statistic of the respondents and the airlines can be observed in Figure 3 below.32

All respondents have more than 15 years of experience and were responsible for teams that performed ground activities, while it was verified that all of them had OHS courses provided by the airlines on a regular basis.

The compilation of information from the interviews was a laborious part of the data analysis step (iii) carried out entirely by the researchers. Once compiled, this information was discussed and validated by the 2 experienced experts. Finally, a closing meeting was held with the representatives of each company to present the compiled results and to check again that there were no interpretation problems.32 An important result of this work was the promotion of a major benchmarking regarding the impacts of COVID-19 on airlines' ground operations. It is important to emphasize that in this final report, the information has been summarized and any reference that allowed the identification of one or more participating airlines has been removed.

The respondents were unanimous in some points related to the impacts caused by the new coronavirus pandemic in airlines. One of which was about the need to reduce costs (CCA-01), such as reducing the aircraft fleet and renegotiating contracts. This finding corroborates the research by Sobieralski3 that points out that companies focused on reducing operating costs better face the crisis generated by the new coronavirus pandemic. Likewise, the work of Maneenop and Kotcharin19 identified that the abrupt decline in demand for travel may require external measures to stop the financial losses of airlines. Therefore, this work contributes to the theory by relating the need to reduce operating costs to airlines, in addition to contributing to the practice by showing that actions such as reducing the aircraft fleet needed to be taken for airlines to survive the pandemic.

All respondents pointed out that companies applied quick actions such as wage reduction and suspension of contracts. In addition, all respondents confirmed that the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in the dismissal of direct employees (CCA-02) and contract closures (CCA-03). All airlines carried out mass layoffs, one of the companies chose to soften the number of layoffs by reducing workload and wages by 30%. Similarly, all the airlines reduced or paralyzed all service contracts, it is worth mentioning that the most affected were the outsourced employees of aircraft cleaning. This result corroborates the research by Amankwah-Amoah8 which points out that employee layoffs were used by airlines to reduce costs. In addition, this result corroborates the research of Sobieralski,3 who identified that the qualification level was a criterion for defining which airline employees would be fired. Therefore, this work contributes to the theory by verifying that the new coronavirus pandemic resulted in the termination of outsourced contracts and layoffs, besides contributing to the practice by detailing those airlines tried to preserve technical know-how in relation to layoffs, therefore people with lower education level were the most affected.33

The national airlines were called by the government to carry out the transport of inputs, medicines, and vaccines (CCA-04), since the national airlines reach all states of the federation in an agile and fast way. It is worth mentioning that foreign airlines have enabled imports with the required quality standard. The transportation of these inputs within the country was carried out at no cost by national airlines, on the other hand, these companies benefited by having their image linked to the COVID-19 action to save Brazilian lives. This result corroborates the research of Dube et al.,12 who stated that the aerial modal is fundamental to carry out the transport of products related to the treatment of coronavirus because of agility, as well as for having trained employees and prepared equipment to transport these types of materials. Therefore, this work contributes to the theory by confirming that airlines were important to transport materials related to the fight against COVID-19, besides contributing to the practice by confirming that these airlines have obtained image improvements, even performing this transport without economic benefits.

However, there was not the same unanimity among the respondents regarding the demonstration of the airlines in valuing the physical and mental conditions of the employees below the wing (CCA-05). While respondents employed by foreign airlines, and by one of the large national airlines, reported a strong positioning of company executives who were noticed through actions such as the implementation of paid leave for employees who did not feel comfortable working during periods of the pandemic, logically with reduced wages. On the other hand, the respondents from the other national airlines and the executive aviation company reported that the companies also adopted actions to support operational employees, however, there was no rigor or collection regarding the application of these actions. Thus, there were no changes in relation to the concern of these companies regarding the physical and mental conditions of employees below the wing. In addition, a climate of fear of contagion by COVID-19 and, consequently, a feeling of uncertainty about layoffs, especially if the employee is contaminated and needs to be removed from the company, was perpetuated. This result corroborates the research by Grout and Leggat5 who stated that airline employees understand the importance of good physical and mental conditions of all those directly involved with operational activities, especially now with the implications imposed by the new coronavirus pandemic. Therefore, this work contributes to the theory by finding that the physical and mental conditions of the operational employees of the airlines are important for the full execution of their tasks. Furthermore, there are practical contributions when it states that operational employees have situational awareness and recognize the importance of their physical and mental conditions. On the other hand, a gap was identified regarding the implementation of actions to combat COVID-19 by some airlines. In addition, it was concluded that there is a connection between the impacts caused by COVID-19 on airlines and the practices to combat COVID-19 recommended by the WHO, as shown in Figure 4.

The availability of materials and resources for proper hand sanitation, as well as body temperature measurement (PCC-01) was confirmed as performed by all the companies of the respondents. It is important to mention two points that have been reported, the first is something positive, the leadership of one of the airlines replaced the hand sanitizer 70% alcohol in gel by 70% liquid alcohol with sprays at the request of ground employees. On the other hand, the respondents of two companies reported distortions in the body temperature measurement procedure, and measurements were performed with flash thermometers by the pulse of employees and not by the forehead, thus, cases of fever were never detected. These results corroborate the research of Spinazzè et al.,4 that points out that 70% alcohol is an important sanitizer if it is not possible to wash your hands with soap and water. Besides corroborating the research by Garzillo et al.,26 which highlights that body temperature measurement helps companies to detect suspected asymptomatic cases of COVID-19. Therefore, this work contributes to the theory by confirming that the use of sanitizers and temperature measurement are relevant to combating the new coronavirus pandemic, besides contributing to the practice by verifying that the feeling of mistrust and fear of contagion is established when hygiene and temperature measurement procedures are not applied correctly.

The supply of PPE (PCC-02) is a common practice in airlines, since inside airports the use of equipment such as safety shoes and ear plugs are mandatory, even before the new coronavirus pandemic. Thus, all respondents stated that the face masks were added to the list of mandatory equipment, however, one of the respondents reported that the company where he worked required the use of this PPE, but only in early 2021 began to provide masks type FPP-2 or N95 and provide training. It is important to mention that one of the foreign companies, besides providing appropriate masks, also provided gloves, face shield and Tyvek type overalls for ground employees, according to the functions performed. These results corroborate the studies by Michaels and Wagner27 and Sotomayor-Castillo et al.,6 that highlight that the main way of SARS-COV-2 contamination is through the respiratory tract, so FPP-2 and N95 masks are more effective in protecting employees. Additionally, this study contributes to the research of O’Neill28 that highlighted the importance of mapping the activities performed in relation to the risks of contagion and correct use of each PPE. Therefore, this work contributes to the theory by relating the use of masks and other PPE to reduce the risks of contagion from COVID-19 to airlines. Furthermore, it contributes to the practice by pointing out the importance of relating the risks of contagion due to the execution of each activity with the efficiency of each type of PPE, besides providing training for the correct use of the masks.

The promotion of social distancing (PCC-03) and the staggering of shift schedule (PCC-04) were practices to combat COVID-19 that clearly divided the respondents into two distinct groups. While employees of foreign airlines and one of the large national airlines were strong in affirming adherence to the protocols while pointing out examples such as changing the opening and closing times of all shifts, as well as changing rest and mealtimes, as well as the installation of acrylic partitions and fixing of tables and chairs, all to avoid agglomerations. However, the other respondents reported that these same procedures were communicated by the responsible managers, but there was no engagement on the part of the operational employees due to the lack of requirement by managers, so the daily perception was that the activities occur in the same way as before the beginning of the pandemic, resulting in a feeling of insecurity in a large portion of these employees. These results corroborate the research by Garzillo et al.,26 O'Neil28 and Parker1 stating that social distancing helps companies combat COVID-19, that scaling shifts avoids agglomerations and that these combat practices are adopted by companies of all types and sizes because they do not require investments. Therefore, this work contributes to the theory by relating the ground activities of airlines with social distancing and shift scheduling, besides contributing to practice by presenting evidence that the efficiency of implementation of these measures is related to the participation of the middle management in work routines.

Similarly, to the previous items, the practice of combating COVID-19 related to cleaning and disinfection of tools, surfaces, and workplaces (PCC-05) kept the respondents separated into two groups, the same presented above. While the first group confirmed that the cleaning team received more efficient products, it was trained to offer a more rigorous cleaning of the common areas, in the same way that it was also reinforced for all employees that they are responsible for the correct cleaning of their items and workplaces, as well as for keeping the environmental well ventilated. On the other hand, the second group of respondents highlighted that a more careful cleaning of the common areas is performed every time the coordinator requests, but this group of respondents reported difficulties for their employees to maintain the individual cleaning of work environments and tools. These results corroborate the research by O'Neill28 and Spinazzè et al.,4 who highlighted that standardized and frequent cleaning procedures assist in controlling the new coronavirus pandemic. Therefore, this work contributes to the theory by emphasizing the importance of cleaning surfaces and tools, in addition to ensuring the natural ventilation of environmental for aviation ground operations. In addition, this work contributes to the practice by stressing the importance of raising awareness and training employees for the correct performance of cleaning procedures to reduce the risk of contagion by the new coronavirus.

Regarding the referral of suspected or confirmed cases of employees with COVID-19 to specialized hospitals (PCC-06), all respondents were unanimous that the airlines perform these procedures correctly. But it is worth mentioning that two respondents reported that their employing company, both national airlines, require that COVID-19 infected employees to visit the work doctors of the companies. So that, only then they can start the removal from the job and, if necessary, take social security measures. This procedure increases the risk of contagion of other employees. These results corroborate the research by Garzillo et al.,26 and O'Neill28 who identified that monitoring and forwarding suspected cases to medical centers specializing in COVID-19 reduces the risk of contagion of all employees of the company. Therefore, this work contributes to the theory by stressing the importance of referring suspected cases of COVID-19 to hospitals also for airline operational employees. Furthermore, there are practical contributions by emphasizing to companies the importance of controlling and monitoring the symptoms of all employees to identify, in a preventive way, the sources of contamination.

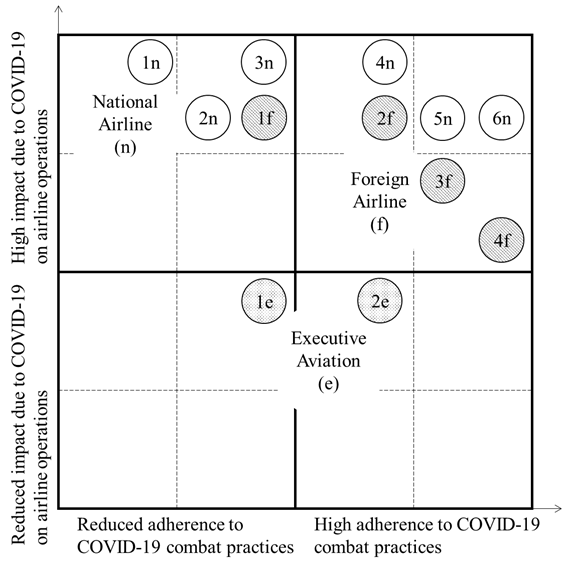

Thus, a graph (Figure 5) was prepared to summarize the results of the interviews and establish a scenario for the 12 participating companies. For this purpose, the impacts of COVID-19 on ground operations and the adherence to practices combatting COVID-19 proposed by WHO were considered.34

Figure 5 Relationship of the impacts of COVID-19 on ground operations with the adherence to the combat practices of COVID-19 by airlines.

It was possible to conclude that national airlines were the most impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. It is important to mention that the biggest national airlines were the ones that most adhered to the combat protocols. Even so, international airlines were also heavily impacted, although less so than national ones, it is worth noting that the not so well positioned are Latin American airlines. Finally, executive transport was less impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic when compared to the other airlines studied, as the drop in demand was more subtle in this type of passenger transport. A brief update was carried out at the end of 2021 to verify the protocols adopted by airlines regarding vaccination. All companies encouraged vaccination, most making the COVID-19 Vaccine mandatory through sanctions and layoffs. On the other hand, some airlines encouraged vaccination with less intensity, only sending e-mails or putting up informational posters.35

In addition, this update allowed to observe that of the 12 airlines studied, 5 airlines reported severe problems that resulted in the drastically reduced or suspended operations, change in the scope of activity or bankruptcy. Logically, these airlines were poorly positioned in Figure 5.

This work analyzed the effects of the new coronavirus pandemic in the operational activities of airports. The important theoretical contributions of this work were evidenced by relating airlines operating in Brazil to the need in reducing costs, closing of service contracts and layoffs. Besides the fact that part of the companies needs to transport hospital supplies free of charge, as well as highlight the importance of the full physical and mental conditions of tarmac employees to correctly perform the activities. Thus, it was also evidenced the reduction of contamination risks of the new coronavirus in the airlines by hand sanitation, use of masks, social distancing, staggering of shift schedules, disinfection of workplaces, and referral of suspected cases to hospitals.

This work presented valuable practical contributions in identifying that the new coronavirus pandemic resulted in a reduction in the number of aircraft in the fleet, as well as caused the dismissal of people with a lower educational level. On the other hand, the image of airlines has been improved by having their activities related to the transportation of vaccines against COVID-19. Furthermore, it was evidenced that employees, in general, have situational awareness. On the other hand, some companies have difficulties in implementing actions to combat COVID-19, either due to lack of monitoring and verification by managers, lack of training and communication activities, or even due to excessive bureaucracy.

In addition, this work contributes to society by disclosing these results to respondents and demonstrating that it is possible to develop scientific work aligned with the interests of companies, in this case, the promotion of benchmarking between airlines. Thus, companies identified as better prepared to deal with the new coronavirus pandemic shared its impacts, effects and detailed how to implement actions to combat COVID-19. In addition, these results aim to raise awareness and provide information, consequently, to pressure airlines to properly implement the actions to combat COVID-19 recommended by WHO.

The new coronavirus pandemic is directly affecting companies from all segments, it is evident that tourism and travel companies were severely affected, thus, all the work developed to analyze the impact in these sectors is relevant. Furthermore, SARS-COV-2 is an airborne virus, however much is still discussed regarding sanitization and temperature measurement. A limitation of this work is considering these health protocols, the most current available. It is recommended for further work to analyze protocols to combat the new coronavirus more directed at air contamination, such as avoiding work in unventilated places or promoting outdoor work.

Finally, airlines are motivated to invest in the duty of care to convey a sense of security to passengers, but little is addressed in relation to this sense of security for employees under the wing. In view of this limitation, future research may continue to explore this research gap.

None.

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

©2022 Tucci, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.