eISSN: 2378-3176

Case Report Volume 6 Issue 1

1Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, USA

2President, Nephrology Hypertension Renal Transplant & Renal Therapy, USA

3CEO, Garden State Kidney Center, USA

4Nephrology Hypertension Renal Transplant and Renal Therapy, USA

Correspondence: Alexander M Swan, AOA Professor of Medicine, Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark, New Jersey, USA, Tel 732-750-5555, Fax 732-750-5550

Received: December 18, 2017 | Published: January 31, 2018

Citation: Swan AM, Kyaw HH, Aye ZN (2018) Therapeutic Response of Natural Adrenocorotropin in Treatment of Proteinuria due to ANCA Negative Pauci-Immune Crescentic Glomerulonephritis. Urol Nephrol Open Access J 6(1): 00198. DOI: 10.15406/unoaj.2018.06.00198

Corticosteroid and immunosuppressive therapies are considered as first-line therapy for patients with idiopathic Focal Segmental Glomerular Sclerosis (FSGS) associated with clinical features of nephrotic syndrome. Choosing medications vary individually with underlying causes, renal function and response to the drugs. Here, we report a case of nephrotic syndrome with nephritic component due to pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis treated with Acthar HP Gel. A 60-year-old white male was diagnosed with biopsy proved Rapidly Progressive Glomerular Nephritis (RPGN) with serum creatinine 3.6 mg/dl, proteinuria (5800 mg/24hr), and GFR 18.6 ml/min/1.73m2 and overweight (BMI > 29) with underlying diabetes (HbA1C 10.6 %), hypertension (180/90 mmHg) and atrial fibrillation which made him concern to use corticosteroids such as prednisolone and his reduced GFR (<18ml/min/1.73m2) favor to avoid calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporine or tacrolimus) as primary treatment. Therefore, he was given adrenocorticotropin (H.P. Acthar gel 80 U/ml once weekly) injection as a preferred alternative for one and a half year. His proteinuria decreased to 1500 mg/24hr and protein/creatinine ratio decreased from 4795 mg/g to 337 mg/g. Serum creatinine reduced back to 1.9 mg/dL and GFR 38.6 ml/min/1.73m2. He achieved partial remission which is >50% of previous baseline with concurrent use of mycophenolate and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers. He has been tolerating well with medications without signs and symptoms of steroid-induced adverse events throughout the treatment with stable proteinuria. These results revealed that the long term use of Acthar gel 80 U/ml once weekly was an effective and safe therapy for patients with idiopathic FSGS and RPGN complicated with diabetic nephropathy.

Keywords: acthar; proteinuria, nephrotic syndrome, crescentic glomerulonephritis

FSGS, focal segmental glomerular sclerosis; RPGN, rapidly progressive glomerular nephritis; MC1Rs, melanocortin 1 receptors; RPR, rapid plasma regain; ANCAs, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies

Many treatment options have been tried to cure the patients with chronic renal insufficiency of various type as idiopathic Focal Segmental Glomerular Sclerosis (FSGS) and Rapidly Progressive Glomerular Nephritis (RPGN) associated with clinical features of nephrotic syndrome. An extensive crescent formation of glomeruli is the characteristic feature of RPNG which usually lead to end-stage renal disease showing the signs of hematuria, decreased urine output, hypertension, fatigue, and edema.1 Laboratory diagnosis in these patients may have high plasma creatinine, marked Glomerular filtration, and proteinuria.2 Some patients may not have hematuria the reason of which is not known.3 Choosing medications for renal insufficiency patients vary individually with underlying causes, renal function and response to the drugs and the results were inconsistent. Most of the first-line therapy used anti-proteinuric drugs, such as corticosteroid and immunosuppressive drugs failed to get a favorable response, mostly due to drug intolerance and side effects,4,5 more seriously in infants.6

Currently Acthar has re-emerged and is the most promising treatment option for proteinuria in patients with nephrotic syndrome, patients for treatment-resistant to first-line therapies, patients unable to tolerate first-line therapies and patients with advanced disease.7–9 Acthar is a repository corticotrophin which binds to the Melanocortin 1 receptors (MC1Rs) and potentially providing a different way to impact various cells including podocytes,10,11 thus help regulate protein filtration by reducing podocyte foot process effacement and podocyte loss.7 The patients treated with Acthar got full or partial remission for long term effect.8 Here, we report the case of a patient suffering from proteinuria due to a mixed nephritic-nephrotic syndrome.

A 60-year-old white male who had previously chronic kidney disease in 2015 with serum creatinine of 1.35 mg/dl with underlying diabetes (+1yr), hypertension (+2yr), and atrial fibrillation (by holter monitor) and hyperlipidemia (+2yr), transurethral resection of the prostate due to Benign prostatic hyperplasia in 2011 and nephrolithiasis (2015), presented with frothy urine, weight gain (10 lbs), fatigue, anorexia and weakness in Feb 2016. He denied any respiratory symptoms such as hemoptysis. He was a non-smoker and occasional social drinker but he stopped drinking since the onset of sickness in 2015. He works as a machine operator in a warehouse and denies exposure to radiation and toxins. There is no history of renal stone, cancer or autoimmune disease in his family.

On physical examination, he was found to have pitting edema, puffy face, and body mass index 29.5, blood pressure 180/90 mmHg. Reviews of other systems were unremarkable. He has been on Benicar–HCT (Olmesartan-hydrochlothiazide), carvedilol, crestor (rosuvastatin). Metformin was discontinued due to renal insufficiency.

Urinalysis was dipstick positive for 2+ blood, 3+protein, and no leukocyte esterase or nitrites. On microscopic examination, there were a few epithelial cells and hyaline casts, and occasional amorphous crystals were seen. Serum sodium, potassium, calcium, phosphorous, and parathyroid hormone level were unremarkable except low vitamin D (20.5ng/ml). Thyroid function test, liver enzymes, coagulation profile and complement profile were normal.

He was negative for cancer screening, hepatitis B and C, HIV, Rapid plasma reagin (RPR), antinuclear antibodies, rheumatoid factor, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs), cardiolipin Ab, lupus panel, glomerular basement membrane antibodies, and cryoglobulin. Completements C3, C4 were normal. Serum and urine protein electrophoresis show no paraprotein.

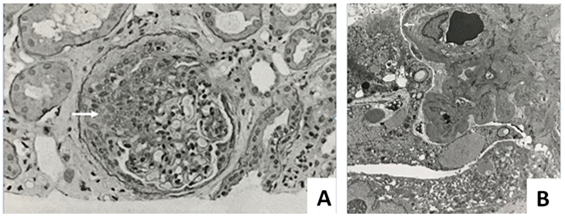

The renal biopsy revealed sub acute and chronic crescentic glomerulonephritis of pauci immune type. The detailed pathology findings included 2 cellular crescents, 7 fibro cellular crescents and 4 fibrous crescents and no active necrosis. There were segmental and global glomerulosclerosis (2/38, 6/38), moderate degree of diffuse acute tubular injury, interstitial fibrosis, tubular atrophy, and arteriolosclerosis. The moderate glomerular basement membrane thickening by electron-micrography may indicate an early, class 1, diabetic glomerulosclerosis (Figure 1).

Figure 1(A) Cresentic glomerulus showing disappearance of normal renal texture (white arrow). (B) Electron-microscopy shows focal segmental glomerulosclerosis showing podocyte foot process effacement (white arrow).

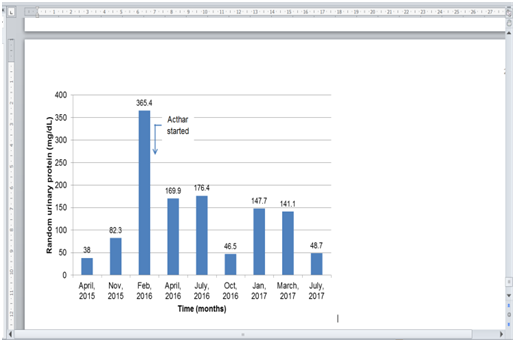

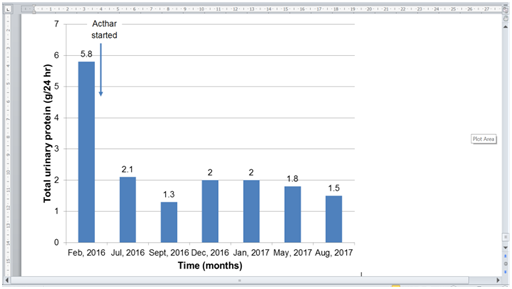

The laboratory test results of the patient done throughout the treatment period were shown in Table 1. From March 2015 to February 2016 the patient’s random urinary protein and serum creatinine increased from 38 to 365.4 (about 10 times) and 1.35 to 3.6 mg/dL, respectively. The Glomerular filtration rate reduced from 58 to 18.6 ml/min/1.73m2. Loss of 24-hour total urinary protein spiked to 5800 mg/24hr (Table 1), (Figures 2 & 3). These facts indicated that the kidneys were turning into severe insufficiency. As the patient’s GFR was<30 mL/min/1.73 m2, the use of calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus or cyclosporine) were avoided for the potential of developing nephrotoxicity of these drugs.12,13 Also, steroids were not suitable to prescribe due to the patient’s overweight and underlying diabetes with high HbA1C level (10.6 %).Therefore, it was decided to give the patient a weekly Acthar injection (80 U/ml) immediately after the result along with mycophenolate 500mg 3 times a day. It was to control proteinuria and to slow disease progression combined with angiotensin receptor blocker (valsartan 160mg twice a day). Mycophenolate level and 24-hour proteinuria were followed.

Figure 2 An abrupt increase in random urinary protein in February 2016. After Acthar treatment, proteinuria fell in 2 months.

Figure 3 The spike of total urinary protein excreted in 24 hour in February 2016. The total proteins for previous months were not measured but the abrupt high excretion was evident by Figure 1.

No |

Test creteria |

Reference |

Mar, 2015 |

April, 2015 |

Nov, 2015 |

Feb, 2016 |

Acthar Started |

April, 2016 |

July, 2016 |

Sept, 2016 |

Oct, 2016 |

Dec, 2016 |

Jan, 2017 |

Mar, 2017 |

May, 2017 |

July, 2017 |

Aug, 2017 |

1 |

Protein/Creatinine ratio, urine(mg/g) |

(0-200) |

476 |

1198 |

4795 |

2151 |

1506 |

618 |

1637 |

1167 |

337 |

||||||

2 |

Total protein, random urine (mg/dl) |

(0 – 15) |

38 |

82.3 |

365.4 |

169.9 |

176 |

46.5 |

147.7 |

141.1 |

48.7 |

||||||

3 |

Total protein, urine (gm/24 hr) |

(0-0.2) |

5.8 |

2.12 |

1.3 |

2 |

2 |

1.8 |

1.5 |

||||||||

4 |

BUN (mg/dl) |

(7-20) |

21 |

29 |

36 |

56 |

49 |

45 |

47 |

45 |

43 |

49 |

34 |

||||

5 |

Serum creatinine (mg/dl) |

(0.6-1.3) |

1.35 |

1.57 |

1.88 |

3.6 |

2.39 |

2.19 |

2.8 |

2.16 |

2.6 |

2.11 |

2 |

2.29 |

1.9 |

||

6 |

Serum albumin (mg/dl) |

(3.4-5.0) |

4.4 |

4.4 |

4.3 |

2.5 |

3.6 |

3.9 |

4.3 |

4.6 |

4.4 |

3.8 |

|||||

7 |

GFR (Non-African American) (ml/min/1.7m2) |

>60 |

58 |

18.6 |

24.8 |

27 |

27 |

36.5 |

38.6 |

||||||||

8 |

Hemoglobin A1C (%) |

(4.8-5.6) |

6.1 |

5.9 |

10.6 |

5.7 |

6.1 |

5.4 |

6.3 |

||||||||

9 |

Triglyceride (mg/dl) |

(50-149) |

73 |

94 |

117 |

81 |

145 |

113 |

203 |

109 |

|||||||

10 |

Cholesterol, Total (mg/dl) |

(120-199) |

168 |

153 |

176 |

166 |

183 |

192 |

181 |

159 |

|||||||

11 |

HDL (mg/dl) |

(40-60) |

47 |

44 |

40 |

47 |

45 |

48 |

40 |

50 |

|||||||

12 |

LDL (mg/dl) |

(0-100) |

106 |

89 |

113 |

112 |

100 |

105 |

118 |

93 |

|||||||

13 |

Hemoglobin (gm/dl) |

(14-18) |

14.8 |

13.2 |

10.8 |

10.7 |

11.9 |

12.3 |

12.9 |

13 |

Table 1 Laboratory test results of the patient from March 2015 to August 2017.

After 5 months of Acthar injection, the 24-hour proteinuria (July 2016), declined significantly from 5800 to 2120 mg/24 hr which is >50% of previous baseline. Also, the protein/creatinine ratio declined from 4795 to 1506 mg/g and serum creatinine from 3.6 to 2.19 mg/dL. His body weight reduced from 194 to 181 lb within 5 months. Blood pressure returned around 130/90 mmHg. Hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C) reduced to 5.7%. The weekly injection of Acthar was continued for 1.5 yr. His comorbid conditions including hyperglycemia, hypertension, hyperlipidemia were also monitored and controlled accordingly.

We managed high blood pressure with hydralazine 10mg oral twice daily which was increased up to 100mg at bedtime later. The other medications include Coreg (Carvedilol) 25 MG Oral daily, Pantoprazole Sodium 40 mg for stomach discomfort, Crestor (Atorvastatin) 40 MG for dyslipidemia and Tanzeum (Albiglutide) 50 MG subcutaneous injection weekly for glycemic control which was later changed to Trulicity (Dulaglutide) 1.5mg subcutaneously weekly. Until writing this report, the patient has been receiving a weekly Acthar injection. It seemed that the continued injection of Acthar was necessary for maintaining the stable condition of the patient.

Regarding other laboratory test criteria, coagulation profile, phosphorus, calcium, parathyroid hormone, sodium, potassium was within normal limit throughout the treatment. Anemia was improved without the need of erythropoietin injection (Hb level increased from 10.8 to 13 gm/dl). Serum albumin was more or less stable maintained around 4 mg/dl. Blood pressure was maintained around 130/80 mmHg and body weight around 180 lb.

These results revealed that the continuous use of Acthar gel 80 U/ml once weekly for more than a year could induce partial remission of proteinuria and maintain the clinical condition without adverse effect for patients with idiopathic FSGS and RPGN complicated with diabetic nephropathy.

None.

None.

©2018 Swan, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.