eISSN: 2378-3176

Research Article Volume 6 Issue 3

Division of Urology, Hospital das Clinicas, University of S

Correspondence: Alexandre Danilovic, Division of Urology, Hospital das Clinicas, University of Sao Paulo Medical School, 255, Dr Eneas de Carvalho Aguiar Avenue, Cerqueira Cesar, 05403-000, Brazil, Tel 55 11 31429077

Received: February 05, 2018 | Published: May 22, 2018

Citation: Danilovic A, Ferreira TAC, Maia GVA, et al. Laparoscopic nephrectomy for urolithiasis: risk factors for conversion. Urol Nephrol Open Access J. 2018;6(3):94-97. DOI: 10.15406/unoaj.2018.06.00211

Background and propose: Nephrectomy may be necessary to treat patients with urolithiasis in case of severe urinary infection or chronic pain in a renal unit with poor function. The aim of this study was to investigate the risk factors for conversion to open procedure in laparoscopic nephrectomy (LN) for urolithiasis.

Patients and methods: Data of all patients > 18 years-old submitted to LN between January 2006 and May 2013 in our Institution were reviewed. Charlson index, ASA score, renal function by MDRD equation and stage, preoperative computed tomography (CT) findings, complications by Clavien-Dindo classification and conversion rate were analyzed. Logistic regression analysis was performed to determine the risk factors for conversion in LN for urolithiasis.

Results: Eighty four patients were submitted to LN and 16 of them (19%) had to be converted to open surgery due to severe adhesion of the renal hilum to surrounding organs in all cases. Other associated causes for conversion were excessive bleeding (n=6) and large intestinal injury (n=3). In univariated analysis, prior renal surgery (p 0.043), perirenal fat stranding (p 0.004), renal abscess (p 0.03), perirenal abscess (p 0.023), pararenal abscess (p 0.006), fistula (p 0.006), adherence to liver or spleen (p 0.015) and adherence to bowel (p <0.0001), were associated to conversion. In multivariate analysis, pararenal abscess (p=0.0052) and adherence to bowel (p <0.0001) were significant risk factors for conversion to open procedure.

Conclusion: Pararenal abscess and adherence to bowel demonstrated on preoperative CT are risk factors for conversion in LN for urolithiasis.

XGP, xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis; LN, laparoscopic nephrectomy; MDRD, modification diet for renal disease; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation; DMSA, dimercapto-succinic acid

The prevalence of kidney stones is approximately 8% of the population and its incidence is increasing over the past two decades in both men and women of different age groups.1 Renal stone disease is a benign pathology, but can cause progressive loss of renal function, end-stage kidney disease and ultimately death.2 Treatment aims to preserve renal function and to eradicate kidney stones. However, nephrectomy may be necessary in case of severe urinary infection or chronic pain in a renal unit with a poor function.3

Laparoscopy is considered the gold standard approach for nephrectomy due to less postoperative pain, short recovery and better cosmetic outcomes. However, the massive inflammatory process that sometimes is associated to complicated stone disease causes technical difficulties owing to the presence of a significant fibrotic component. The ultimate presentation in this scenario is xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis (XGP), accompanied by perirenal fat proliferation that infiltrates the renal fossa structures, including the renal hilum.4 Owing to its severe inflammatory nature, distinct surgical complications are expected from those found in nephrectomy for donation or kidney cancer.5 Furthermore, some patients present with adverse conditions such as renal abscess, renocutaneous fistula and visceral or intestinal adhesions. Conversion rate to open procedure is expected to be higher in patients with renal stone comparing with other affections.6

In this retrospective study, we searched for preoperative predictive factors for conversion to open surgery in laparoscopic nephrectomy (LN) for urolithiasis.

Patients

We retrospectively evaluated all consecutive patients > 18 years of age submitted to LN for urolithiasis from January 2006 to May 2013 in a tertiary reference center. Nephrectomy was accomplished due to pain in excluded renal units or severe urinary infection. Initial surgical approach was proposed by the surgeon and discussed with the patient. Informed consent was obtained for all patients. The local Institutional review board approval of the study protocol was obtained.

Pre operative assessment

Renal function was assessed by the equation of the Modification Diet for Renal Disease (MDRD)7 for estimated glomerular filtration rate and staged according to National Kidney Foundation. Split renal function was estimated by 99m technetium dimercapto-succinic acid renal scintigraphy (99mTc-DMSA). Comorbidities were evaluated by Charlson Index and by American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score.8 Computed tomography was obtained preoperatively in all patients. Findings of hydronephrosis, fat stranding, abscess, and adherence to surrounding structures were based on radiologists’ report.

Operative technique

Surgeries were performed by residents under direct supervision of an experienced laparoscopic surgeon. LN was performed through transperitoneal approach. Under general anesthesia, patients were positioned in a 45-degree supine-oblique position. Pneumoperitoneum was created with CO2 up to 15 mmHg intra abdominal pressure. Four trocars were used (two of 10mm and two of 5mm). On the right side, an extra trocar was positioned in the epigastric region to move the liver cranially and adequately expose the right kidney. The kidney and peri-renal fat were dissected outside the Gerota fascia.5 The renal hilum was approached as close as possible to the inferior vena cava, on the right side, and to the aorta on the left side. Renal arteries and veins were clipped with Hem-o-lock® clips and divided. The ureter was clipped and sectioned close to the iliac vessels. The specimen was removed morcellated in a bag through the umbilical incision or undivided through suprapubic incision. Pathologic analysis was performed in all cases.

Post-operative complications

Post-operative complications were reported according to Clavien-Dindo classification.9

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were analyzed using Chi-square and Fisher's exact test and continuous variables using t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA). We performed a logistic regression analysis to evaluate the association between clinical and pathological data and the risk of conversion to open surgery. Statistical analyzes were conducted with the aid of SPSS Statistics v16.0 (Chicago, SPSS Inc).

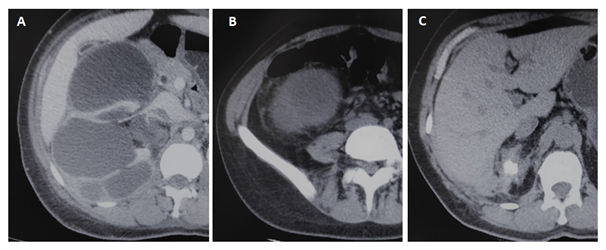

Eighty four patients with a poor functioning kidney associated to pain or severe infection were submitted to nephrectomy in our Institution (Table 1). The main tomographic findings were hydronephrosis (71.4%), fat stranding (63%) and adherence to liver/spleen (29.6%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Preoperative tomographic findings in patients submitted to laparoscopic nephrectomy for urolithiasis: (A) Hydonephrosys, (B) Fat stranding, (C) Adherence to liver.

Gender (Female) |

67 (79.7) |

Age (mean±SD) |

47.8±14.2 |

BMI (mean±SD, kg/m2) |

26.6±5.5 |

Prior Renal Surgery |

37 (44) |

Renal Size (mean±SD, cm) |

11.7±3.83 |

Left Kidney |

44 (52.3) |

DMSA renal scan (mean±SD, %) |

8±9.8 |

MDRD (mean±SD, ml/min/1.73m2) |

69.45±28.03 |

Charlson Index (mean±SD) |

1.26±1.9 |

ASA Score |

|

1 |

22 (26.2) |

2 |

52 (61.9) |

3 |

8 (9.5) |

4 |

2 (2.4) |

Staghorn Stone |

47 (55.9) |

Tomographic Findings |

|

Hydronephrosis |

60 (71.4) |

Fat stranding |

53 (63) |

Renal Abscess |

15 (17.8) |

Perirenal Abscess |

7 (8.3) |

Pararena lAbscess |

3 (3.5) |

Adherence to liver/spleen |

25 (29.6) |

Adherence to bowel |

20 (23.8) |

Adherence to muscle |

16 (19) |

Table 1 Preoperative data, n = 84 (%)

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation; MDRD, modification of diet in renal disease formula; DMSA, dimercapto-succinic acid; ASA, american society of anesthesiologists.

Conversion rate was 19% (16 of 84 patients). The main cause of conversion was inadequate exposure of the renal hilum due to severe adhesion and inflammation, seen in all converted cases. Other causes for conversion included excessive bleeding during the operation (6/16, 37.5%) and large intestinal injury (3/16, 18.8%).

Complications according to Clavien classification are summarized in Table 2. Two vena cava injuries were repaired by running laparoscopic suture. Open splenectomy was performed in the immediate postoperative period in one patient due to splenic laceration. There were five intestinal injuries: two duodenal, one repaired laparoscopicaly and other converted to open procedure, one colonic and one small bowel injuries that resulted in conversion. One patient evolved to death due to unrecognized colonic injury and peritonitis. Pathological reports are stated in Table 3.

I |

62(73.8) |

II |

11(13.1) |

III a |

3(3.5) |

III b |

1(1.2) |

IV a |

5(5.9) |

IV b |

1(1.2) |

V |

1(1.2) |

Table 2 Complications according to Clavien classification, n (%)

Xanthogranulomatous Pyelonephritis |

16 (19) |

Atrophy |

18 (21.4) |

Chronic Pyelonephritis |

32 (38) |

Pyonephrosis |

10 (11.9) |

Nephrocalcinosis |

8 (9.5) |

Table 3 Pathology report, n (%)

In univariate analysis, conversion was significantly associated to prior renal surgery (68.7% vs. 38.2%, p 0.043), perirenal fat stranding (97.3% vs. 55.8%, p 0.004), renal abscess (37.5% vs. 13.2%, p 0.03), perirenal abscess (25% vs. 4.4%, p 0.023), pararenal abscess (18.7% vs. 0%, p 0.006), fistula (18.7% vs. 0%, p 0.006), adherence to liver or spleen (56.2% vs. 23.5%, p 0.015) and adherence to bowel (75% vs. 11.7%, p <0.0001) (Table 4). In multivariate analysis, only pararenal abscess (p=0.0052) and adherence to bowel (p <0.0001) were significant risk factors for conversion (Table 5). Postoperative hospital stay was relatively higher in the conversion group (5.4±3.1 vs. 3.19±2,3 days, p 0.005).

|

Conversion n=16 (%) |

Pure Laparoscopy n=68 (%) |

p-value |

Female |

13 (81.2) |

54 (79.4) |

1 |

Age > 70y |

1 (62) |

2 (3.0) |

0.474 |

BMI >=30 (kg/m2) |

2 (12.5) |

18 (26.4) |

0.336 |

Prior Renal Surgery |

11 (68.7) |

26 (38.2) |

0.043 |

DMSA <20% |

15 (93.7) |

63 (92.6) |

1 |

Charlson>2 |

7 (43.7) |

16 (23.5) |

0.125 |

ASA Score |

0.557 |

||

1 |

4 (25.0) |

18 (26.4) |

|

2 |

9 (56.2) |

43 (63.3) |

|

3 |

3 (18.7) |

5 (7,3) |

|

4 |

0 (0.0) |

2 (3.0) |

|

Kidney Size≥ 12cm |

7 (43.7) |

17 (25) |

0.217 |

Tomographic Findings |

|||

Hydronephrosis |

11 (68.7) |

49 (72.0) |

0.767 |

Fat stranding |

15 (93.7) |

38 (55.8) |

0.004 |

Renal abscess |

6 (37.5) |

9 (13.2) |

0.033 |

Perirenal abscess |

4 (25.0) |

3 (4.4) |

0.023 |

Pararenal abscess |

3 (18.7) |

0 (0.0%) |

0.006 |

Fistula |

3 (18.7) |

0 (0.0%) |

0.006 |

Adherence to liver/spleen |

9 (56.2) |

16 (23.5) |

0.015 |

Adherence to bowel |

12 (75.0) |

8 (11.7) |

<0.0001 |

Adherence to muscle |

5 (31.2) |

11 (16.1) |

0.175 |

Pathological diagnosis |

|||

XanthogranulomatousPyelonephritis |

6(37.5) |

10 (14.7) |

0.105 |

Atrophy |

2 (12.5) |

16 (23.5) |

0,449 |

ChronicPyelonephritis |

6(37.5) |

26 (38.2) |

0.711 |

Pyonephrosis |

2(12.5) |

8 (11.7) |

0.165 |

Nephrocalcinosis |

2 (12.5) |

6 (8.9) |

0.105 |

Table 4 Univariate analysis of risk factors for conversion in laparoscopic nephrectomy for urolithiasis

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; MDRD, modification of diet in renal disease formula; ASA, american society of anesthesiologists.

Chi-square |

p-value |

|

Fat stranding |

0.121 |

0.728 |

Renal Abscess |

0 |

0.9996 |

Perirenal Abscess |

0.016 |

0.8978 |

Pararenal Abscess |

7.808 |

0.0052 |

Adherence to liver/spleen |

3.007 |

0.0829 |

Adherence to bowel |

30.424 |

<0.0001 |

Table 5 Multivariate analysis of risk factors for conversion in laparoscopic nephrectomy for urolithiasis

Laparoscopy is the procedure of choice for performing nephrectomy.10 Contemporary the vast majority of nephrectomies are performed for donation or treatment of renal cancer.10,11 Nephrectomy due to complications of urolithiasis is performed in few situations, including renal units with poor function associated to chronic pain, symptomatic or recurrent infections, abscess or fistulae formation and suspect malignant degeneration.3

LN due to urolithiasis is a challenging procedure requiring a skillful surgical team. The inflammatory process creating a toxic fat involves the renal hilum leading to a very difficult isolation of the renal artery and vein. Moreover, bulky adenopathy, adhesion to bowel, liver, spleen, pancreas or muscle are frequent. En block clamping or initial clamping of the renal vein are eventually required maneuvers to get control of the renal hilum, diverting from standard nephrectomy. On certain occasions, it is impossible to find a cleavage plane between the large vessels and the urinary tract, forcing the surgeon to leave patches of kidney tissue adhered to these structures. On the right side, the difficulty is even higher due to the nearby vena cava and the duodenum. In our series, we observed two cases of duodenum injury and two cases of vena cava tearing repaired by laparoscopic suture. Such technical difficulties lead many urologists to question the laparoscopic approach in such cases.12,13 In this scenario, the literature suggests that LN due to stones and inflammatory disease should be performed approaching the kidney outside the Gerota fascia leading to a safer procedure.14

However, conversion rate is still higher than observed in LN for other conditions. Zelhof and colleagues, in a study of 142 cases, selected from all the nephrectomies performed in the United Kingdom owing to a benign pathology, demonstrated higher conversion rates to open procedure in patients with renal calculi than for radical nephrectomy for T1 disease.15 A recent retrospective study with 96 laparoscopic nephrectomies for stone diseaseevidenced a conversion rate of 7.2%.16 Conversion to open procedure was necessary because it proved impossible to dissect the renal hilum owing to xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis (n=4) or major associated lesions (n=3). Our study reports19% (16/84) conversion rate in nephrectomies exclusively for urolithiasis. In all converted cases, the appropriate access to the renal hilum was impeded due to the intense inflammatory process. Conversion to open nephrectomy also impacts in longer hospital stay (5,4±3,1 vs. 3,19±2,3 days, p 0,005), underlying the importance of choosing the proper access prior to nephrectomy.

There are few evidences in the medical literature establishing predictive factors for open conversion in LN Angerri et al.16 showed that extensive areas of pyelonephritis are a major risk for conversion. Rassweiler et al.17 reported seven conversions to open procedures in a multicentric study with 482 LN of which two involved an XGP kidney. In our series, there were more cases with XGP in conversion group (25.0% vs. 14.7%; p=0.105), however there was no significant difference between groups regarding pathological findings.

Previous renal ipsilateral surgery increases difficulty due to anatomical changes in renal units that have already been operated, in addition to scarring processes and adhesions to nearby tissues.6 In our study, cases with prior renal surgery were more frequent among converted procedures but this fact was not significant in a multivariate analysis.

Preoperative enhanced CT scan plays an important role demonstrating calculi, hydronephrosis, determining the extension of the inflammatory process, evidencing abscesses, fistulae (renocolic or cutaneous) and adherences to adjacent structures (psoas muscle, back or abdominal wall muscles, pancreas, liver and spleen) which predict an upcoming complex procedure (Figure 1). Herein we demonstrated the key importance of tomographic features in predicting conversion to open nephrectomy. In univariate analysis, fat stranding, renal, perirenal and pararenal abscess, fistula and adherences to adjacent structures were significantly more frequent in the conversion group. Multivariate analysis revealed that pararenal abscess and adherence to the bowel were significant risk factors for conversion to open procedure. All patients who presented a pararenal abscess on preoperative tomography had their procedures converted to open access, which gives this parameter statistical significance even with a reduced number (n=3).

There are several limitations of our study as the small number of cases and its retrospective nature. However, as far as we know, this is the first report to look for preoperative predictive factors for conversion from laparoscopic to open nephrectomy due to stone disease. A prospective multi institutional study with a large number of patients is desired to confirm our data.

In conclusion, conversion rate for LN due to urolithiasis was 19% in our series. Risk factors for conversion to open nephrectomy were pararenal abscess and adherence to the bowel as identified in preoperative CT. In these cases, the procedure is associated with an increased degree of technical difficulty. Therefore, Initiating nephrectomy by the open access should be considered.

None.

Authors declare there is no conflict of interest in publishing the article.

©2018 Danilovic, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.