Mini Review Volume 4 Issue 3

Evaluation of the cardiovascular prior to transplantation; an endless debate

Tariq Zayan,1,2

Regret for the inconvenience: we are taking measures to prevent fraudulent form submissions by extractors and page crawlers. Please type the correct Captcha word to see email ID.

Ahmed Aref,1,2 Ajay Sharma,2,3 Ahmed Halawa2,4

1Department of Nephrology, Sur hospital, Oman

2Faculty of Health and Science, Institute of Learning and Teaching, University of Liverpool, UK

3Royal Liverpool University Hospitals, Liverpool, UK

4Sheffield Teaching Hospitals, Sheffield, UK

Correspondence: Ahmed Halawa, Consultant Transplant Surgeon, Sheffield Teaching Hospitals, Sheffield, Herries Road-Sheffield, S5 7AU, UK, Tel 00 447787542128, Fax 00 44114 271 4604

Received: February 24, 2017 | Published: March 14, 2017

Citation: Zayan T, Aref A, Sharma A, Halawa A (2017) Evaluation of the Cardiovascular Prior to Transplantation; An Endless Debate. Urol Nephrol Open Access J 4(3): 00126. DOI: 10.15406/unoaj.2017.04.00126

Download PDF

Abstract

Cardiovascular disease continues to be the most important cause of death after transplantation. Although there is a dramatic improvement in the diagnosis and management of cardiovascular disease, the rate of cardiovascular death after kidney transplantation still higher compared to general population. Chronic kidney disease is associated with many risk factors that lead to increased incidence and prevalence of cardiovascular diseases. In this mini-review, we will discuss recent advances in cardiovascular work up prior to kidney transplantation.

Keywords: Cardiovascular disease; Workup; Assessment and renal transplantation

Abbreviations

ESRD: End Stage Renal Disease; CKD: Chronic Kidney Disease; KDOQI: Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative; AHA: American Heart Association; CAD: Coronary Artery Disease; ICA: Invasive Coronary Angiography; SPECT: Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography; MPI: Myocardial Perfusion Imaging; DSE: Dobutamine Stress Echocardiography; DS-CMR: Dobutamine Stress Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging; PAD: Peripheral Arterial Disease; ABI: Ankle-Brachial Index; CTA: Computed Tomography Angiography; MRA: Magnetic Resonance Angiography

Cardiovascular Assessment

Although renal transplantation reduces cardiovascular morbidity and mortality compared to end stage renal disease (ESRD), it is associated with an early increase of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [1-9]. Renal transplantation recipients should undergo rigorous screening processes considering not only peri-operative risk, but also must be designed to provide information regarding CV risk in the early years post-transplantation [10,11]. There is no universally accepted screening process especially in asymptomatic chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients given their high cardiac risk even if asymptomatic [8,12-27]. All recipients must be tested by non-invasive methods as recommended by Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) guidelines and the only determinant for testing by American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACR/AHA) guidelines were functional status tempered by risk factor profile [18,19].

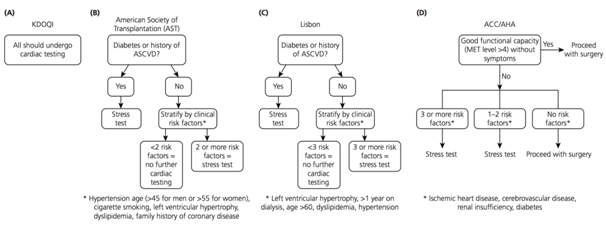

Intermediate levels of testing result from application of guidelines developed by more kidney-specific stakeholder groups (Figure 1) (Table 1) [20,21]. As conventional CV risk factors are highly prevalent in this population, exclusion of coronary artery disease (CAD) comprises a substantial component of CV screening in higher risk transplant candidates [17]. There is no consensus on which technique will be optimal when deciding that cardiovascular screening is mandatory [22-25]. The presence or absence of chest pain provides little clinical certainty in distinguishing between the presence and absence of significant CAD in potential renal transplant recipients [23,26-30]. There is substantial debate regarding the necessity to perform invasive coronary angiography (ICA) to exclude significant CAD prior to transplantation. Numerous studies have been published demonstrating the advantages and limitations of non-invasive investigations in the ESRD context [27,31-33].

Non-Invasive Cardiovascular Assessment of Potential Kidney Transplant Recipient |

|

Resting Electrocardiography

Conventional Echocardiography

Stress Electrocardiography

Stress echocardiography either exercise or pharmacologic

Myocardial perfusion scan

Carotid intimal medial thickness

Cardiopulmonary exercise test

Computed tomography coronary angiography

Magnetic resonance angiography

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging

Electron beam computed tomography

Digital subtraction fluorography

|

Table 1: Non-invasive cardiovascular assessment of potential kidney transplant recipient.

Figure 1: Cardiac risk assessment of four guidelines.

Exercise-based stress testing is widely accepted as the preferred, and most accurate, methodology for the non-invasive exclusion of coronary ischaemia. Uraemia, however, is commonly associated with reduced exertional capacity, frequently preventing ESRD patients from achieving the necessary level of tachycardia required to minimize the occurrence of a false negative result. Previous studies have demonstrated a higher risk of future cardiovascular events amongst patients unable to complete exercise stress tests, regardless of the presence of a negative result. Thus combinations of exercise and vasodilatory agents, or dobutamine infusion have been utilized to optimize non-invasive imaging results [34-36].

Conventionally, exercise (+/- dipyridamole or adenosine) or dobutamine single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI) have been the most commonly utilized investigation in the non-invasive exclusion of ischaemia prior to RTx. Dobutamine stress echocardiography (DSE) is a commonly utilized alternative, with some results indicating a higher specificity attributable to this investigation, but similar overall accuracy in non- renal failure patients [37,38].

The presence of a negative study does not entirely exclude the presence of haemodynamically significant coronary artery disease, hence the preference within some RTx centres to rely solely upon ICA for the evaluation of coronary risk in this context, however are associated with procedural risk [32]. Myocardial perfusion studies and dobutamine stress echocardiography (DSE) show equally well results in diagnosing patients with stenosis ≥50% of a major coronary artery, which supported by Cochrane meta-analysis [39].

Data from large studies on general populations shows similar or superior outcomes of medical treatment over revascularization, except in triple vessel disease [15,40-42]. Alternatively, recent data from CKD studies compared to the general population confirm compromised therapeutic responses to medical treatment [43]. As diabetics have high risk of cardiac events and poor negative predictive value of non-invasive test, some advice use of cardiac catheterization as sole for prediction of adverse cardiac events in diabetics waiting transplantation [44,45]. Dobutamine stress Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging (DS-CMR) has recently been demonstrated to provide a very high level of accuracy in the non-invasive detection of significant CAD, with low procedural risk [46-49].

Which results at cardiovascular assessment prevent transplantation? This is difficult to judge. Most centers currently will consider ischemia not responsive to revascularization as contraindication to transplantation. Similarly, after revascularization of advanced coronary disease, severe left ventricular dysfunction considered contraindication to transplantation as it associated with high mortality [50]. On the other hand, absence of coronary disease in the presence of severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction considered as indication for transplantation as many reports confirm cardiac function improvement after restoration of kidney function in adult and pediatric. Many dialysis patients have pulmonary hypertension which worse with duration on dialysis. Data from recent studies shows increased risk of graft and/or patient loss in advanced elevation of right ventricular systolic pressure ≥50mmHg [50]. Some data suggest that high right ventricular systolic pressure considered as contraindication to transplantation till treated. Finally, it is mandatory to manage advanced valvular heart disease before transplantation [51].

Assessment for Peripheral Vascular Disease

There is an absolute indication for vascular assessment including general assessment of prognosis as well as specific assessment of the vascular supply needed for the transplant operation. Atheromatous iliac arteries that have been ossified through years of CKD management must thus be carefully assessed by the surgeon planning to perform the transplant [52-54]. The presence of peripheral arterial disease (PAD) and its degree could be assessed by noninvasive tests. These tests include ultrasound, segmental limb pressures, the ankle-brachial index (ABI), segmental volume plethysmography, and exercise treadmill test. Furthermore, recent data suggest that computed tomography angiography (CTA) and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) have become important noninvasive methods for the PAD assessment [55-60]. Arteriography still considered as gold standard for diagnostic evaluation of PAD. Nowadays, to establish the diagnosis of PAD and to plan the most adapted intervention, most vascular specialists use three-dimensional reconstructed angiography (CTA or MRA) or bidimensional images obtained with Duplex-ultrasound modalities [59-61]. However, diagnostic standard angiography may still remain necessary, in selected cases [62,63].

Conclusion

Cardiovascular screening and intervention for transplant recipient especially asymptomatic patients are common practice but the clear benefits of these interventions still questionable. Large Randomized controlled trial is needed to clearly define the risk/benefit of the current practice.

References

- Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Knoll G, Bello A, Browne S, et al. (2011) Systematic review: kidney transplantation compared with dialysis in clinically relevant outcomes. Am J Transplant 11(10): 2093-2109.

- Aakhus S, Dahl K, Wideroe TE (1999) Cardiovascular morbidity and risk factors in renal transplant patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 14(3): 648-654.

- Oniscu GC, Brown H, Forsythe JL (2005) Impact of cadaveric renal transplantation on survival in patients listed for transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol 16(6): 1859-1865.

- Rabbat CG, Thorpe KE, Russell JD, Churchill DN (2000) Comparison of mortality risk for dialysis patients and cadaveric first renal transplant recipients in Ontario, Canada. J Am Soc Nephrol 11(5): 917-922.

- Schnuelle P, Lorenz D, Trede M, Van Der Woude FJ (1998) Impact of renal cadaveric transplantation on survival in end-stage renal failure: evidence for reduced mortality risk compared with hemodialysis during long-term follow-up. J Am Soc Nephrol 9(11): 2135-2141.

- Shrestha A, Basarab-Horwath C, McKane W, Shrestha B, Raftery A, et al. (2010) Quality of life following live donor renal transplantation: A single center experience. Ann Transplant 15(2): 5-10.

- Tomasz W, Piotr S (2003) A trial of objective comparison of quality of life between chronic renal failure patients treated with hemodialysis and renal transplantation. Ann Transplant 8(2): 47-53.

- Gill JS, Ma I, Landsberg D, Johnson N, Levin A (2005) Cardiovascular events and investigation in patients who are awaiting cadaveric kidney transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol 16(3): 808-816.

- Ojo AO, Hanson JA, Meier-Kriesche H, Okechukwu CN, Wolfe RA, et al. (2001) Survival in recipients of marginal cadaveric donor kidneys compared with other recipients and wait-listed transplant candidates. J Am Soc Nephrol 12(3): 589-597.

- Ritz E, Schwenger V, Wiesel M, Zeier M (2000) Atherosclerotic complications after renal transplantation. Transpl Int 13 Suppl 1: S14-19.

- Karthikeyan V, Ananthasubramaniam K (2009) Coronary risk assessment and management options in chronic kidney disease patients prior to kidney transplantation. Curr Cardiol Rev 5(3): 177-186.

- Gaston RS, Basadonna G, Cosio FG, Davis CL, Kasiske BL, et al. (2004) Transplantation in the diabetic patient with advanced chronic kidney disease: a task force report. Am J Kidney Dis 44(3): 529-542.

- Danovitch GM, Hariharan S, Pirsch JD, Rush D, Roth D, et al. (2002) Management of the waiting list for cadaveric kidney transplants: report of a survey and recommendations by the Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Society of Transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol 13(2): 528-535.

- Knoll G, Cockfield S, Blydt-Hansen T, Baran D, Kiberd B, et al. (2005) Canadian Society of Transplantation: consensus guidelines on eligibility for kidney transplantation. CMAJ 173(10): S1-25.

- Pilmore H (2006) Cardiac assessment for renal transplantation. Am J Transplant 6(4): 659-665.

- Kasiske BL, Israni AK, Snyder JJ, Camarena A, COST Investigators (2011) Design considerations and feasibility for a clinical trial to examine coronary screening before kidney transplantation (COST). Am J Kidney Dis 57(6): 908-916.

- Friedman SE, Palac RT, Zlotnick DM, Chobanian MC, Costa SP (2011) A call to action: variability in guidelines for cardiac evaluation before renal transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6(5): 1185-1191.

- Fleisher LA, Beckman JA, Brown KA, Calkins H, Chaikof E, et al. (2007) ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and care for noncardiac surgery: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines (writing committee to revise the 2002 guidelines on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation for noncardiac surgery): developed in collaboration with the American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Rhythm Society, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, and Society for Vascular Surgery. Circulation 116(17): 1971-1996.

- K/DOQI Workgroup (2005) Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for cardiovascular disease in dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 45(4 Suppl 3): S1-S153.

- Abbud-Filho M, Adams PL, Alberu J, Cardella C, Chapman J, et al. (2007) A report of the Lisbon conference on the care of the kidney transplant recipient. Transplantation 83(8 Suppl): S1-S22.

- Friedman SE, Palac RT, Zlotnick DM, Chobanian MC, Costa SP (2011) A call to action: variability in guidelines for cardiac evaluation before renal transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6(5): 1185-1191.

- De Lima JJ, Sabbaga E, Vieira ML, de Paula FJ, Ianhez LE, et al. (2003) Coronary angiography is the best predictor of events in renal transplant candidates compared with noninvasive testing. Hypertension 42(3): 263-268.

- Kahn MR, Fallahi A, Kim MC, Esquitin R, Robbins MJ (2011) Coronary artery disease in a large renal transplant population: implications for management. Am J Transplant 11(12): 2665-2674.

- Hickson LJ, Cosio FG, El-Zoghby ZM, Gloor JM, Kremers WK, et al. (2008) Survival of patients on the kidney transplant wait list: relationship to cardiac troponin T. Am J Transplant 8(11): 2352-2359.

- de Mattos AM, Siedlecki A, Gaston RS, Perry GJ, Julian BA, et al. (2008) Systolic dysfunction portends increased mortality among those waiting for renal transplant. J Am Soc Nephrol 19(6): 1191-1196.

- Sharma R, Pellerin D, Gaze DC, Gregson H, Streather CP, et al. (2005) Dobutamine stress echocardiography and the resting but not exercise electrocardiograph predict severe coronary artery disease in renal transplant candidates. Nephrol Dial Transplant 20(10): 2207-2214.

- Sharma R, Pellerin D, Gaze DC, Shah JS, Streather CP, et al. (2005) Dobutamine stress echocardiography and cardiac troponin T for the detection of significant coronary artery disease and predicting outcome in renal transplant candidates. Eur J Echocardiogr 6(5): 327-335.

- Braun WE, Phillips DF, Vidt DG, Novick AC, Nakamoto S, et al. (1984) Coronary artery disease in 100 diabetics with end-stage renal failure. Transplant Proc 16: 603-607.

- Margolis JR, Kannel WS, Feinleib M, Dawber TR, McNamara PM (1973) Clinical features of unrecognized myocardial infarction--silent and symptomatic. Eighteen-year follow-up: The Framingham study. Am J Cardiol 32(1): 1-7.

- Rostand SG, Kirk KA, Rutsky EA (1986) The epidemiology of coronary artery disease in patients on maintenance hemodialysis: implications for management. Contrib Nephrol 52: 34-41.

- Bart BA, Cen YY, Hendel RC, Lee R, Marwick TH, et al. (2009) Comparison of dobutamine stress echocardiography, dobutamine SPECT, and adenosine SPECT myocardial perfusion imaging in patients with end- stage renal disease. J Nucl Cardiol 16(4): 507-515.

- Enkiri SA, Taylor AM, Keeley EC, Lipson LC, Gimple LW, et al. (2010) Coronary angiography is a better predictor of mortality than non-invasive testing in patients evaluated for renal transplantation. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 76(6): 795-801.

- Gowdak LH, de Paula FJ, Cesar LA, Martinez Filho EE, Ianhez LE, et al. (2007) Screening for significant coronary artery disease in high- risk renal transplant candidates. Coron Artery Dis 18(7): 553-558.

- Worthley MI, Unger SA, Mathew TH, Russ GR, Horowitz JD (2003) Usefulness of tachycardic-stress perfusion imaging to predict coronary artery disease in high- risk patients with chronic renal failure. Am J Cardiol 92: 1318-1320.

- Al Jaroudi W, Iskandrian AE (2009) Regadenoson: a new myocardial stress agent. J Am Coll Cardiol 54(13): 1123-1130.

- Navare SM, Mather JF, Shaw LJ, Fowler MS, Heller GV, et al. (2004) Comparison of risk stratification with pharmacologic and exercise stress myocardial perfusion imaging: a meta-analysis. J Nucl Cardiol 11(5): 551-561.

- Mahajan N, Polavaram L, Vankayala H, Ference B, Wang Y, et al. (2010) Diagnostic accuracy of myocardial perfusion imaging and stress echocardiography for the diagnosis of left main and triple vessel coronary artery disease: a comparative meta-analysis. Heart 96(12): 956-966.

- Picano E, Molinaro S, Pasanisi E (2008) The diagnostic accuracy of pharmacological stress echocardiography for the assessment of coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Ultrasound 6: 30.

- Wang LW, Fahim MA, Hayen A, Mitchell RL, Baines L, et al. (2011) Cardiac testing for coronary artery disease in potential kidney transplant recipients. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 12: CD008691.

- Manske CL, Wang Y, Rector T, Wilson RF, White CW (1992) Coronary revascularisation in insulin- dependent diabetic patients with chronic renal failure. Lancet 340(8826): 998-1002.

- McFalls EO, Ward HB, Moritz TE, Goldman S, Krupski WC, et al. (2004) Coronary-artery revascularization before elective major vascular surgery. N Engl J Med 351(27): 2795-2804.

- Poldermans D, Schouten O, Vidakovic R, Bax JJ, Thomson IR, et al. (2007) A clinical randomized trial to evaluate the safety of a noninvasive approach in high-risk patients undergoing major vascular surgery: the DECREASE-V pilot study. J Am Coll Cardiol 49(17): 1763-1769.

- Bansal N, Hsu CY, Chandra M, Iribarren C, Fortmann SP, et al. (2011) Potential role of differential medication use in explaining excess risk of cardiovascular events and death associated with chronic kidney disease: a cohort study. BMC Nephrology 12: 44.

- Welsh RC, Cock eld SM, Campbell P, Hervas-Malo M, Gyenes G, et al. (2011) Cardiovascular assessment of diabetic end-stage renal disease patients before renal transplantation. Transplantation 91(2): 213-218.

- Jardine AG, Gaston RS, Fellstrom BC, Holdaas H (2011) Prevention of cardiovascular disease in adult recipients of kidney transplants. Lancet 378(9800): 1419-1427.

- Gebker R, Jahnke C, Hucko T, Manka R, Mirelis JG, et al. (2010) Dobutamine stress magnetic resonance imaging for the detection of coronary artery disease in women. Heart 96(8): 616-620.

- Kelle S, Egnell C, Vierecke J, Chiribiri A, Vogel S, et al. (2009) Prognostic value of negative dobutamine-stress cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Med Sci Monit 15(10): MT131-136.

- Wallace EL, Morgan TM, Walsh TF, Dall'Armellina E, Ntim W, et al. (2009) Dobutamine cardiac magnetic resonance results predict cardiac prognosis in women with known or suspected ischemic heart disease. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2(3): 299-307.

- Jahnke C, Nagel E, Gebker R, Kokocinski T, Kelle S, et al. (2007) Prognostic value of cardiac magnetic resonance stress tests: adenosine stress perfusion and dobutamine stress wall motion imaging. Circulation 115(13): 1769-1776.

- Issa N, Krowka MJ, Gri MD, Hickson LJ, Stegall MD, et al. (2008) Pulmonary hypertension is associated with reduced patient survival after kidney transplantation. Transplantation 86(10):1384-1388.

- Fleisher LA, Beckman JA, Brown KA, Calkins H, Chaikof EL, et al. (2009) American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2009 ACCF/AHA focused update on perioperative beta blockade incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and care for noncardiac surgery. Circulation 120: e169-e276.

- Nankivell BJ, Lau S-G, Chapman JR, O'Connell PJ, Fletcher JP, et al. (2000) Progression of macrovascular disease after transplantation. Transplantation 69(4): 574-581.

- Eggers PW, Gohdes D, Pugh J (1999) Nontraumatic lower limb extremity amputations in the Medicare end-stage renal disease population. Kidney Int 56(4): 1524-1533.

- Wong G, Howard K, Chapman JR, Chadban S, Cross N, et al. (2012) Comparative survival and economic benefits of deceased donor kidney transplantation and dialysis in people with varying ages and co-morbidities. PLoS One 7(1): e29591.

- Rofsky NM, Adelman MA (2000) MR angiography in the evaluation of atherosclerotic peripheral vascular disease. Radiology 214(2): 325-238.

- McPhail IR, Spittell PC, Weston SA, Bailey KR (2001) Intermittent claudication: an objective office-based assessment. J Am Coll Cardiol 37(5): 1381-1385.

- McDermott MM, Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM, Dyer AR, Liu K, et al. (2010) The ankle-brachial index is associated with the magnitude of impaired walking endurance among men and women with peripheral arterial disease. Vasc Med 15(4): 251-257.

- Koelemay MJ, den Hartog D, Prins MH, Kromhout JG, Legemate DA, et al. (1996) Diagnosis of arterial disease of the lower extremities with duplex ultrasonography. Br J Surg 83(3): 404-409.

- Menke J, Larsen J (2010) Meta-analysis: Accuracy of contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance angiography for assessing steno-occlusions in peripheral arterial disease. Ann Intern Med 153(5): 325-234.

- Ota H, Takase K, Igarashi K, Chiba Y, Haga K, et al. (2004) MDCT compared with digital subtraction angiography for assessment of lower extremity arterial occlusive disease: importance of reviewing cross-sectional images. AJR Am J Roentgenol 182(1): 201-209.

- Bonvini RF, Roffi M (2010) Tools & techniques: aortoiliac and common femoral endovascular interventions. Euro Intervention 6(2): 288-289.

- Tang GL, Chin J, Kibbe MR (2010) Advances in diagnostic imaging for peripheral arterial disease. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 8(10): 1447-1455.

- Owen AR, Roditi GH (2011) Peripheral arterial disease: the evolving role of non-invasive imaging. Postgrad Med J 87(1025): 189-198.

©2017 Zayan, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the,

which

permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.