eISSN: 2378-3176

Research Article Volume 4 Issue 1

Department of Urology, P D Hinduja National Hospital and Medical Research Center, India

Correspondence: Mahendra Pal, Department of Urology, P D Hinduja National Hospital and Medical Research Center, Mahim, Mumbai, India, Tel 400016 9757091924

Received: August 24, 2016 | Published: January 18, 2017

Citation: Pal M, Joshi VS, Sagade SN (2017) Does Temporary Catheter Drainage of Urine Improves Detrusor Function in Chronic Urinary Retention in Patients with Bladder Outlet Obstruction? Urol Nephrol Open Access J 4(1): 00114 DOI: 10.15406/unoaj.2017.04.00114

Chronic urinary retention (CUR) is one of the consequences of bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) that occurs due to impaired functions of detrusor muscles secondary to obstruction related changes in the bladder wall. The effect of catheter drainage (CD) on detrusor function in CUR in animals is well studied but in humans there are very few studies to see its effect in CUR.

Material and methods: This is a non-randomized, retrospective study wherein case records of 50 eligible patients attending the Department of Urology during January 2010 to March 2012 were evaluated for CUR. Two UDS, performed 6-12 weeks (average 9 weeks) apart and the parameters which were evaluated were bladder sensation, capacity and voiding detrusor pressure. These parameters were also evaluated against the age of the patient, duration of symptoms and the amount of urine drained on catheterization.

Results: The commonest symptoms observed were decrease flows of urine, frequency, straining and incomplete emptying. Bladder function improvement after CD was observed to be maximum in patients with following characteristics: age at presentation in the range of > 60 to < 70 years, duration of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) less than 5 years and amount of urine drained at the time of catheterization being < 500 ml.

Conclusion: CUR secondary to BOO is a common problem in elderly males. UDS is the “gold standard” for its evaluation and helps to plan further management. CD of urine is an effective mode of temporary management in patients of CUR secondary to BOO as it provides rest to the detrusor muscle in humans.

Keywords: Bladder outlet obstruction; Urinary bladder; Chronic urinary retention; Catheter drainage; Urodynamic study

CUR: Chronic Urinary Retention; BOO: Bladder Outlet Obstruction; CD: Catheter Drainage; LUTS: Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms; PVR: Post Void Residual; DM: Detrusor Muscle; DP: Detrusor Pressure; UDS: Urodynamic Study; SPC: Suprapubic Catheter; LUT: Lower Urinary Tract

Chronic urinary retention (CUR) secondary to bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) in spite of being a frequently encountered clinical problem, there are lacunae in the understanding of its patho mechanisms and management protocols in humans. International Continence Society defined CUR as “a non-painful bladder, which remains palpable or percussible after the patient has passed urine” [1]. However the practiced definition of CUR is “post void residual (PVR) urine of >300 ml in men who are voiding, or >1000 ml in men who are unable to void” [2,3].

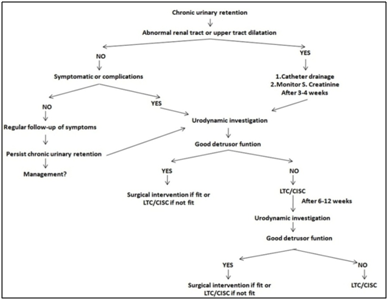

The pathophysiology in CUR secondary to BOO revolves around the decrease contractile strength of the detrusor muscle (DM) which causes incomplete evacuation of urine. In initial phases of BOO, DM undergoes hypertrophy with increase collagen deposition in the stroma. This helps to increase the detrusor pressure (DP) there by compensating for obstruction and maintaining the urinary flow [4-6]. In due course of time, changes in vascular supply and neural innervations of DM occur, which eventually results in reduced DM sensitivity and contractility and leads to detrusor weakening or failure resulting in CUR [7-9]. Classification of CUR has been attempted on various basis [10-15] (Table 1). The key investigation in CUR is the “Urodynamic study” (UDS), and is also the ‘gold standard’ for measuring DP and guide to plan further management [14]. Most treatment options are based on “expert opinion,” however there are no established guidelines for the management of CUR secondary to BOO due less number of evidences [16-18] (Figure 1). This study attempts to evaluate the effect of temporary catheter drainage (CD) of urine on detrusor function in CUR with the help of UDS in men with BOO along with the factors that influence detrusor recovery.

|

By Clinical Evaluation |

Inability of the patient to pass urine: Complete or Partial |

|

|

3

|

Urodynamic Study |

A) High pressure chronic retention (HPCR): The bladder pressure is more than 30 cm |

Table 1: Classification of CUR.

This is a retrospective, non-randomized study. 50 patients reporting to the department of urology during January 2010 and March 2012 were evaluated for the lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), including the clinical history and urodynamic evaluation with appropriate inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 2). The study was approved by the institutional review board. Forty eight patients presented with indwelling Foley’s catheter with an average duration of 3 weeks (range 2-4 weeks) during their first visit, two patients had suprapubic catheter (SPC) of an average duration of 2.5 weeks (range 2-3 weeks). The amount of urine drained on initial catheterization was recorded from previous documents. UDS was performed within 4 weeks after catheterization recorded as first UDS study. A second UDS was done approx 6-12 weeks after the first. Standard multichannel UDS was followed in all case.

|

Inclusion Criteria |

|

|

Male sex |

|

Exclusion Criteria |

||

7.

8. |

Subjects with following ailments: |

|

Table 2: Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Definitions and criteria used

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were described as means, standard deviations and ranges. For categorical variables percentages were used. A value of p <0.05 was considered significant. All tests were performed using SPSS version 16 statistical package under the guidance of a bio-statistician.

Patients were grouped into 4 different categories of age group for analysis purpose. What are the 4 categories? (It is unclear to follow in the following sentences/Paragraph. Please list the 4 groups first before the details). The mean age of presentation was 71 years (52-90 years). Majority of the men were seen in the age group of 70-80 years constituting 44% (n=22) of the study population (Table 3). The commonest symptoms were decrease flow of urine, frequency, straining and incomplete emptying observed in 46 patients, thin stream was the least common presentation observed in 4 patients only, 4 patients were asymptomatic (Figure 1). Patients were divided into three categories of duration of symptoms and most of the patients (n=23, 46%) had symptoms since 0-5 years. The average duration of symptoms was 8.5 years, ranging from 2-15years (Figure 2). Patients were divided in to three categories of amount of urine drained <500 ml (n=12), 501-1000 ml (n=31), >1000 ml (n=7). Bladder function was assessed in all patients by UDS evaluation.

Age Group |

No. of Patients |

Percentage |

< 60 |

03 |

6 |

≥ 60 < 70 |

14 |

28 |

≥ 70 < 80 |

22 |

44 |

≥ 80 |

11 |

22 |

Total |

50 |

100 |

Table 3: Age-wise distribution of patients.

Bladder compliance was normal in all patients. Overall improvement in UB sensation was noticed in all age groups and was statistically significant (p <0.001). However, the improvement in < 60 years was not statistically significant in spite of reduction in mean volume of urine being present during 2nd UDS evaluation (Table 4). There was an improvement noted in the capacity of UB during UDS and was statistically significant (p <0.001) except for age group < 60 years (Table 5). DP was assessed in different age groups in which significant improvement was observed during 2nd UDS evaluation. This improvement in DP after catheterization was statistically significant (P<0.001). However no statistically significant change was seen in the age group of <60 years (Table 6). Grades of voiding detrusor function in various age groups: Most of the patients (n=31) showed improvement in detrusor function. Maximum improvement was noticed in age group >60 to <70 years (78.5%), (Table 7).

Age Group |

1st UDS Evaluation |

2nd UDS Evaluation |

Paired t-test |

||

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

||

< 60 |

337.67 |

196.64 |

276.67 |

92.18 |

0.440 (NS) |

≥ 60 - < 70 |

260.142 |

113.10 |

158.79 |

74.00 |

0.001 (S) |

≥ 70 - < 80 |

321.23 |

157.21 |

203.36 |

121.64 |

0.000 (S) |

≥ 80 |

321.82 |

143.11 |

217.64 |

124.64 |

0.023 (S) |

Total |

305.24 |

143.41 |

198.42 |

110.58 |

P<0.001 |

Table 4: Comparison of Sensation on UDS evaluation in various age groups after temporary CD.

Age Group |

1st UDS Evaluation |

2nd UDS Evaluation |

Paired t-test |

||

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

||

< 60 |

466.33 |

57.93 |

304.00 |

142.79 |

0.085 (NS) |

≥ 60 - < 70 |

442.50 |

177.01 |

270.00 |

147.74 |

0.000 (S) |

≥ 70 - < 80 |

513.87 |

191.50 |

320.59 |

115.30 |

0.000 (S) |

≥ 80 |

526.20 |

258.64 |

360.10 |

246.00 |

0.015 (S) |

Total |

493.50 |

195.97 |

313.18 |

157.98 |

p<0.001 (S) |

Table 5: Age-wise improvement in bladder capacity after temporary CD.

Age Group |

1st UDS Evaluation |

2nd UDS Evaluation |

Paired t-test |

||

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

||

< 60 |

28.33 |

5.77 |

53.00 |

18.36 |

0.190 (NS) |

≥ 60 - < 70 |

18.57 |

15.77 |

55.79 |

34.06 |

0.001 (S) |

≥ 70 - < 80 |

15.87 |

14.24 |

46.35 |

27.36 |

0.000 (S) |

≥ 80 |

19.10 |

12.92 |

42.50 |

13.81 |

0.000 (S) |

Total |

18.02 |

14.07 |

48.62 |

26.81 |

P < 0.001 (S) |

Table 6: Comparison of Detrusor Pressure after temporary CD.

Age Groups |

No. of Patients |

Grades of Detrusor Function Improvement |

||

Improved |

Mild Improvement |

No Improvement |

||

< 60 |

3 |

2 (66.6.) |

0 |

1(33.3) |

>60--<70 |

14 |

11(78.5) |

1(7.1) |

2(14.2) |

>70--<80 |

22 |

13(59) |

7(31.81) |

2(4.5) |

>80 |

11 |

5(45.5) |

6(54.5) |

0 |

Total |

50 |

31 |

14 |

5 |

Table 7: Age wise improvement in detrusor function after temporary CD.

Correlation between duration of symptoms and grades of detrusor function: Although improvement in detrusor function was seen with lesser duration of symptoms, it was statistically insignificant (p = 0.124) (Table 8). Comparison of grades of detrusor function and amount of urine drained: Improvement in detrusor function was observed in 11 patients (91.6%) in whom the amount of drained urine was < 500ml. The amount of urine drained did not show statistically significant influence on detrusor function (Table 9).

Duration of Symptoms |

No of Patients |

Grades of Detrusor Function Improvement |

χ2 test |

||

Improved |

Mild Improvement |

No Improvement |

|||

0 -5 |

23 |

18(78.2) |

3(13) |

2(8.6) |

χ2 = 7.24 |

5-10 |

19 |

9(47.3) |

8(42) |

2(10.5) |

|

>10 |

4 |

1(25) |

2(50) |

1(25) |

|

Total |

50 |

28 |

13 |

5 |

|

Table 8: Correlation between duration of symptoms and improvement in detrusor function after temporary CD.

Amount of Urine Drained |

No. of Patients |

Grades of Detrusor Function Improvement |

χ2 test |

||

Improved |

Mild Improvement |

No improvement |

|||

<500 |

12(24) |

11(91.6) |

- |

1(8.3) |

χ2 = 7.07 |

501-1000 |

31(62) |

16(51.61) |

12(38.7) |

3(9.6) |

|

>1000 |

7(14) |

4(57.1) |

2(28.5) |

1(14.2) |

|

Total |

50 |

31 |

14 |

5 |

|

Table 9: Correlation between urine drained and grades of detrusor function after temporary CD.

CUR secondary to BOO occurs in elderly and DM is significantly damaged [16]. Although being a common clinical entity seen by clinicians there is sparse evidence of its pathophysiology and management guidelines in humans (Figure 3). A total of 50 study patients were evaluated in our study and most of the patients i.e. 22 (44 %) belonged to the age group of >70 to < 80 years, followed by 14 (28%) patients in > 60 to <70 years age group. This was consistent with the clinical findings, as physiological changes in lower urinary tract (LUT) along with prostatic enlargement occurs with aging and it is not uncommon in elderly men to ignore their urinary symptoms due to misbelieve that these are part and parcel of normal changes of aging which leads to delay in seeking treatment [11-13]. Also, many patients with BOO initially prefer medical management. However, a substantial number of these patients have disappointing results and coupled with reluctance to avoid surgery. These patients eventually present as CUR at a later stage thus a advanced age group presentation with CUR is observed [13, 16-27].

Underlining the significance of aging in CUR in their review, Miegs JB et al. [13] and Ian K Walsh et al. [15] concluded that the age was an important risk factor for developing CUR. They found that the incidence of CUR increases with age from 0.4 /1000 person in age group 45-49 years to 7.9/1000 person in age 70-80 years and also that the risk of having CUR was 1/10 in 7th decade which increases to 1/3 in 8th decade. A review by Davies JA [17] stated that the average age of developing CUR secondary to BOO was 66 years. It was associated with co morbidities contributing to urinary problems. They observed that the average age at which patient develops detrusor failure (overflow incontinence) was 71 years which is consistent with the findings of the present study.

In our study 46 (92%) patients gave prior history of LUT symptoms, 4 (8%) patients were asymptomatic. Commonest symptoms observed were decrease flow of urine, frequency, straining, incomplete emptying in 46 patients followed by intermittency, nocturia, hesitancy, incontinence and thinning of stream. This is in agreement with the observations made by Davies JA [17] in their review that the common symptoms of which the patients are aware of are frequency, decrease flow and hesitancy. A retrospective study by SA Kaplan et al. [19] concluded that most common symptom of BOO was nocturia followed by increase frequency of urine, decrease flow of urine, hesitancy, dribbling, straining, sensation of incomplete voiding and incontinence.

All patients in our study had painless retention of urine probably due to impaired sensitivity of bladder and detrusor contractility due to bladder distension in CUR. Many studies demonstrated that in BOO there is recruitment of neural-detrusor responses causing altered neural control of micturition resulting in reduced bladder contractility, impaired central processing, and altered sensation [28-32]. Gosling et al. [9] in a prospective study showed that BOO leads to decrease in the autonomic innervations of human DM which in turn results in decrease sensitivity of bladder.

Greenland Je et al. [33] and Kershen et al. [34] studied in pig and human respectively and concluded that blood flow in bladder reduces with distension that leads to detrusor ischemia and its impaired function. It has been shown in animal model that after reliving the obstruction, these changes are reversible as muscle mass returns to near normal, sensation and compliance improves and bladder capacity decreases. To regain the normal bladder function, it is necessary to give rest to the fatigued detrusor muscle. This is achieved by CD of UB through per urethra, SPC or operative intervention. Continuous urinary drainage through catheter bypasses the BOO, keeps bladder in collapse state and provides rest to DM [35-39]. UDS is the gold standard for measuring detrusor contractile dysfunction and quantitating the degree of BOO [14, 40-46].

Limited data is available on determining the effect of temporary catheter drainage in patients with CUR secondary to BOO using UDS. Siroky et al. [47] in a their prospective study of elderly population by UDS demonstrated that aging is associated with a reduced bladder capacity, an increase in uninhibited contractions, decreased urinary flow rate, diminished urethral pressure profile, and increased PVR urine volume. In our study the patients underwent UDS evaluation for parameters like compliance, sensation, capacity and bladder pressure on two occasions separated by duration of 6-8 weeks. The results analysed after the 2nd UDS evaluation revealed overall improvement in sensation, capacity and bladder pressure which was statistically significant (p <0.05) in all age groups except for age group of less than 60 years. This could probably be attributed to less number of patients in this age group in our study.

All patients in our study had normal compliance. The overall improvement in UDS parameters observed in our study was consistent with the findings of Hautmann et al. [35] prospective study on UDS evaluation in CUR which concluded that temporary catheter drainage of the bladder results in improved compliance, sensation, and maximum bladder capacity after low pressure drainage through SPC for average 13.6 weeks however compliance in our patient was normal on presentation and after temporary CD. The patients that benefited most on catheter drainage had following characteristics on UDS evaluation: Age group on presentation in the range of > 70 to < 80 years, duration of symptoms less than 5 years, and amount of urine drained on presentation being < 500 ml.

Patients in whom least improvement was observed were in the age group of < 60 years, duration of symptoms > 10 years and amount of urine drained on presentation was being > 1000 ml. Many studies reveal that the duration of symptoms has adverse effect on bladder function as the long term bladder distension leads to irreversible ultrastructural changes in detrusor muscle and bladder wall but at what time period these irreversible changes occur, it is not clearly defined. Kershen RT [34] and Ohnishi N et al. [37] postulated that long term distension of bladder leads to DM ischemia which leads to decrease bladder contractility and impaired bladder emptying causing CUR.

Gabella G et al. [38] observed that in animal long term retention leads to detrusor damage due to increase collagen content in bladder wall and impaired contractility of detrusor. All these studies directly or indirectly indicate that more the duration, more the chance of detrusor damaged in CUR due to BOO. Bob Djavan et al. [46] reviewed that patients with age more than 80 years, residual urine of more than 1000 ml and initial voiding detrusor pressure less than 28 cm H2O on presentation was associated with less chances of detrusor recovery after relieving the BOO.

Selius BA et al. [12] stated in their prospective study on urinary retention in adults stated that the first step in management of CUR is to use indwelling catheter to decompress the bladder for up to one month which contributes to reversing the impaired detrusor function. Ghalayini IF et al. [36] in a prospective study emphasized the usefulness of clean intermittent self catheterization (CISC) in the recovery of bladder function in men with CUR. He kept the patient on CISC before TURP and found good improvement in bladder function as per UDS findings in patients with CISC. N Ohnishi et al. [37] and Gabella et al. [38] in their study on rabbits and rats respectively concluded that changes observed in later stages of BOO like reduced detrusor contractility, increased muscle mass, decrease compliance secondary to collagen deposition were reversible after reliving the obstruction. They observed that the hypertrophied muscle weight and mass became near normal six weeks after releasing the obstruction and that no degeneration of muscle cell or nerve endings was seen . This study documents the great plasticity of the musculature in the reduction of muscle mass after de-obstruction. Releasing the obstruction was equal to CD and same results can be reproduced by CD.

The major limitations of the current study were its retrospective nature, small sample size and shorter duration of follow up. A prospective study with a larger sample size and a control group is required to confirm the findings of this study. But nonetheless as there are very few studies in humans which have evaluated the detrusor function after CD in CUR patients secondary to BOO and almost none having evaluated the factors influencing the detrusor function after CD, we attempt to fill these lacunae through the present study.

Temporary CD in CUR has significant beneficial effect on DM recovery in patients with BOO and should be part of initial management. Age of presentation, duration of BOO and amount of urine drained at presentation have clinically significant influence on detrusor recovery in patients undergoing CD thus the management protocol should be individualized to have a favourable outcome. UDS remains the gold standard for diagnosis and evaluation of DM recovery in CUR in BOO after temporary CD. Prospective studies are needed to validate expected management of CUR.

©2017 Pal, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.