eISSN: 2377-4304

Research Article Volume 8 Issue 2

1Gelecek The Center For Human Reproduction, Turkey

2Department of Business, Akdeniz Universitesi Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences, Turkey

Correspondence: Mete Isikoglu, Gelecek Tup Bebek Merkezi, Turkey, Tel 90-5542149493, Fax 90-242-3232010

Received: July 24, 2016 | Published: November 17, 2017

Citation: Malabanan ML, Zamora BB (2017) Think Twice before Abdominal Delivery: Adverse Effects of Caesarean Section on Fertility and on Embryo Transfer Procedure. Obstet Gynecol Int J 8(2): 00285. DOI: 10.15406/ogij.2017.08.00285

Objective: Although several studies have reported lower birth rates subsequent to Caesarean section (CS) in comparison with vaginal delivery (VD), there is no consensus yet. In addition, there is not any study focusing on the association between difficult transfer and a history of CS. We aimed to reveal these two issues.

Material and methods: This retrospective cohort study was conducted at private IVF center. Medical records of all patients presented with the diagnosis of secondary infertility. Group I included 47 patients with a history of at least one CS, group II included 33 patients with a history of VD. In order to compare the rate of CS among secondary infertile women at our clinic (59%) with the official CS rate in Turkey (45%), we performed Z score analysis.

Results: Calculated Z value was higher (2,55) than the statistically significant Z score level (1,96) which reflects a probably higher rate of infertility among women with a history of CS. We came upon difficulty during embryo transfer in four cases all of which were in group I. The implantation rates for CS and ND groups were 19,7% and 27,3% respectively. Even though there was a tendency in favor of ND group it did not reach a statistically significant level.

Conclusion: There seems an association between CS and subsequent infertility. The probability of encountering a difficult embryo transfer may also be a concern in case of IVF treatment.

Keywords: Caesarean section, infertility, embryo transfer

There is a marked increase in caesarean section (CS) rates over the past three decades all over the World1 which is an issue of international public health concern. In the United Kingdom in 2010, the CS rate was 24.8% whereas statistics from 2010-2011 for Australia and the United States of America show almost one in every three pregnant women has a Caesarean delivery.2 Alternative procedures are encouraged such as version and extraction, vaginal breech or instrumental delivery, and symphysiotomy in order to reduce these high rates.3 Apart from the well known per-operative complications and problems of CS in the early post-operative period, concern arouse about the adverse association between CS and fertility due to this considerable increase in abdominal mode of delivery. Investigations focused on infertility, parity and inter-birth interval among women who delivered by CS versus those who delivered vaginally. Despite there are studies claiming no association between mode of delivery and subsequent fertility;4,5 based on the balance in the literature, CS seems to be associated with subfertility and longer inter-pregnancy intervals compared to vaginal delivery.6-10 Even data from a very low income region of the World pertaining 22 Sub-Saharan African countries where most CSs are emergency operations for extreme maternal indication are concordant with findings from developed countries. The natural fertility rate subsequent to delivery by CS was found to be 17% lower than the natural fertility rate subsequent to vaginal delivery.8

In Turkey, the tendency of both the practitioners and the patients towards CSincreased the CS rates in a more steep pattern during the last three decades compared with the other parts of the world.11 Apart from the associated plausable medical problems, this unaccaptable increase in CS rates resulted in a considerable burden on health care budget and made it one of the most urgent problems to be solvedsuch that the law-makers have also participated the debate.12 Although the problem is discussed from the social and political point of view mainly in the media as a hot topic; interestingly enough that there are not enough scientific publications from Turkey about the association of CS and related problems, e.g. infertility/subfertility.13 In this study, we retrospectively analysed clinical data of our IVF center to reveal the association of CS on subsequent fertility as well as the effect of previous mode of delivery on IVF outcome. Particularly, as a novel point of view we aimed to show the effect of a prior CS on embryo transfer technique in IVFprocedures.

This retrospective investigation conducted at Gelecek The Center For Human Reproduction received Institutional Review Board approval. Medical records of all patients presented with the diagnosis of secondary infertility between June 2008 and January 2016 were reviewed. The definition of secondary infertility was done based on the guidelines of World Health Organization: “Following a previous pregnancy, failure to achieve a clinical pregnancy after 12 months or more of regular unprotected sexual intercourse”.14 Two patient groupswere constructed (Figure 1). Group I included 47 patients with a history of at least one CS regardless of the outcome of the newborn. Group II included 33 patients with a history of vaginal delivery (VD) regardless of the outcome of the newborn. Women with a history of both vaginal and CS deliveries (# 5) were allocated in group I. Among these five patients, none of them had the last delivery vaginally. Women who underwent any procedure during the delivery that would definitely or potentially impair future fertility (tubal ligation, oophorectomy, endometrial ablation etc) were excluded. None of the women had abdominal surgery for non-obstetric reasons during the time after last delivery.

Controlled ovarian stimulation (COS) was done according to short flexible antagonist protocol. Gonadotropin stimulation was commenced with recombinant FSH 150 IU/dayor 225 IU/day depending on the ovarian reserve based on antral follicle count on day 2 or day 3 of the menstual cycle and continued until at least two follicles ≥18mm were detected. hCG 250 mcg (Ovitrelle® Merck Serono Turkey) was administered followed 36 hours later by oocyte retrieval. Only grade I and grade II embryos were deemed eligible for embryo transfer. Embryo transfers and luteal phase supports were performed as described elsewhere.15 Briefly, all embryo transfers were performed by the same practitioner (M.I.) under transabdominal ultrasound guidance as patients had full bladders; Sydney IVF® Embryo Transfer Set was used (COOK®, IN, USA). Clinical pregnancies were confirmed by ultrasound detection of an intrauterine gestational sac with cardiac activity 3 weeks after embryo transfer. The association between the route of previous delivery and infertility was the primary study outcome. In addition demographic factors, patients’ age, husbands’ age, and body mass indices (BMIs), and stimulation parameters, number of embryos replaced and clinical outcomes were recorded. Student-t test, Z test, Fisher’s exact test, Pearson Chi square tests were used for the statistical analyses where appropriate. A p value less than alfa value 0.05 was considered significant.All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Program for Social Sciences (SPSS version 12; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

The demographic, stimulation, embryo transfer and pregnancy parameters recorded for the two groupswere compared. Eleven patients in group Ihad two CSs while two of them had three CSs in their obstetric history. In order to compare the rate of CS among secondary infertile women at our clinic (59%)with the official CS rate in Turkey (45%), we performed Z score analysis (Significance Test of Population Ratio). Calculated Z value was higher (2,55) than the statistically significantZ score level (1,96) which reflects a probably higher rate of infertility/subfertility among women with a history of CS compared to that of women with a history of VD. Demographic data were similar for the two groups (Table 1). Etiological reasons for infertility (Table 2), stimulation characteristics (Table 3) and laboratory parameters (Table 4) are depictedin the tables below respectively. Peak endometrial thickness was significantly lower in group I.We came upon difficulty during embryo transfer in 4 cases all of which were in group I. Two out of these cases presented with retroverted uterus. Clinical outcome variables for the two groups are shown in Table 5. The implantation rates for CS and ND groups were 19,7% and 27,3% respectively. Even though there was a tendency in favor of ND group, Z score analysis showed a Z value of 0,77 which was not statistically significant.

|

Group I (#47) |

Group II (#33) |

p |

|

|

Patients’ agea |

36,3±4,6 |

34,6±5,4 |

0,117 |

|

Husbands’agea |

40,0±5,3 |

37,8±5,4 |

0,072 |

|

BMI |

25,4±4,4 |

25,9±4,0 |

0,599 |

Table 1 Baseline charcteristics of the patients

BMI: Student-t test was used for the statistical analysis of the data

|

Group I |

Group II |

p |

|

|

Male factor |

7 (14,9%) |

4 (12,1%) |

0,496 |

|

Tubal factor |

8 (17%) |

6 (18,2%) |

0,893 |

|

Ovulatory factor |

19 (40,4%) |

11 (33,3%) |

0,519 |

|

Endometriozis |

2 (4,3%) |

0 (0,0%) |

0,342 |

|

Unexplained |

7(14,9%) |

6(18,2%) |

0,695 |

|

Combined |

4(8,5%) |

6(18,2%) |

0,172 |

Table 2 Etiological reasons for infertility

Fisher’s exact test: Male factor, Endometriozis, Combined; Pearson Chi-square test: Tubal factor, Ovulatory factor, Unexplained

|

Student-t test |

Group I |

Group II |

P |

|

Length of stimulation |

8,5±2,1 |

9,0±1,5 |

0,221 |

|

Gonadotropin units |

2088±721 |

2091±566 |

0,986 |

|

Peak endometrial thickness |

11,6±2,1 |

12,8±2,2 |

0,014* |

|

No of embryos transferred |

1,5±0,7 |

1,3±0,5 |

0,350 |

Table 3Stimulation characteristics

|

Group I |

Group II |

p |

|

|

No of total oocytes |

9,1±7,0 |

10,2±7,9 |

0,534 |

|

No of MII oocytes |

4,2±4,6 |

5,3±5,7 |

0,335 |

|

Fertilization rate |

75,8±24,9 |

80,2±21,3 |

0,410 |

|

Use of IVF |

15 (31,9%) |

7 (21,2%) |

0,291 |

|

Blastocyst ET |

14 (29,8%) |

11 (33,3%) |

0,736 |

|

Difficult transfer |

4 (8,5%) |

0 (0,0%) |

0,113 |

Table 4 Laboratory variables

Student-t test: No of total oocytesa, No of MII oocytesa, Fertilization ratea; Pearson Chi-square test: Use of IVF, Blastocyst ET; Fisher’s exact test: Difficult transfer

|

Group I |

Group II |

p |

|

|

Clinical pregnancy |

14 (29,8%) |

13 (39,4%) |

0,371 |

|

Miscarriage rate |

3 (6,4%) |

3 (9,1%) |

0,482 |

Table 5 Clinical outcome variables

Pearson Chi-square test : Clinical pregnancy; Fisher’s exact test: Miscarriage rate.

There are numerous studies about the effect of CS on fertility and on the time to subsequent pregnancy. Although there are methodological weaknesses as well as significant variation in the design and the methods of the studies included in the meta analyses, the history of CS has been shown to decrease the chance of having a subsequent pregnancy.6,7 Subfertility after CS can be a result from infection at the wound site or pelvic adhesions as well as medical, obstetrical, social and socioeconomic confounding factors or maternal choice.16 Whether the relation is causal or due to patient selection or bias is still on debate. In their critical review including nearly 600.000 patients, Gurol-Urganci and co-workers found a 9 % lower subsequent pregnancy rate.7 With citation tracking method and without any language restriction, they analysed a total of ten eligible studies and found a 11% lower birth rate due to previous CS. But they did not meta-analyse subsequent pregnancy interval, which is arguably a more robust marker of sub-fertility. Later on, the same group published the analysis of more than one million patients pertaining to twelve years of their national database and revealed the medical and social circumstances may have contribute more to the observed reduction in fertility than the CS itself.17 This is the largest cohort study analysing the association between mode of delivery and fertility. In another recent meta-analysis including two additional further publications, the waiting time to next pregnancy and risk of sub-fertility among women with a previous CS was investigated and the overall findings of the meta-analysis suggested that there was a 10% increased risk of subsequent sub-fertility following CS compared to VD. [pooled odds ratio (OR) 0.90; 95% CI 0.86, 0.93].9 In another retrospective cohort study compiling more than 50.000 patients with a follow up over 8 years, also showed that 40.2% of women with a Caesarean first birth did not have a subsequent live birth, compared with 33.1% of women with a vaginal first birth (risk ratio (RR): 1.21, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.18-1.25). Adjustment for the demographic confounders attenuated the RR to 1.16 (95% CI: 1.13-1.19).18 Several previous studies also claimed that even though an association exists, it is unlikely that delivering by CS per se in a first pregnancy decreases a woman's likelihood of having a second viable pregnancy.4,9

Based on the report of the Turkish Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology (TJOD), CS rates have risen three-fold in Turkey within ten years time: from 6 % in 1988 to 21 % in 1998. Currently it is estimated to be above 45% and strategies have been established to decrease it below 35%.11,12 A brief list for theplausible reasons for this increase may include:the changingsocial point of view of the general population, the influence by the dramatical changes in the health service policy of the government, increasing medicolegal cases the obstetricians face, insufficient speciality training system of the students and residents. The analysis of the increase CS rate is out of the scope of this article. Nevertheless, the long term problems of the CS mothers are starting to bother the new generation specialists. In the present study, we found that having an abdominal delivery have an adverse effect on the future fertility. Several explanations have been proposed regarding the association between CS and subfertility including pelvic adhesions and placental bed disruption as well as the confounding factors and the social choice of the couples regarding reproduction.13,16 In our study, reproductive choice is not a confounding factor for sure since all couples were admitted to an IVF clinic for the aim of conception. Peak endometrial thickness in CS group was found to be significantly lower in CS group. Theoretically, this can be attributed directly to CS procedure per se. Removing the placenta manually in CS soon after the delivery of the baby without waiting for natural detachment may be a contributing factor. In almost all CS cases, manual detachment is followed by a tactile control of the cavity by scratching with gauze in hand or monted in a forceps. This manupilation and/or instrumentation may in turn causepartial synaechia or at least placental bed disruption.

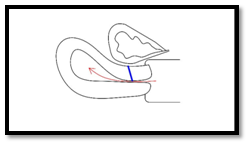

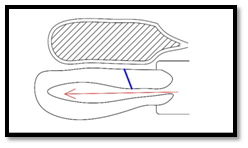

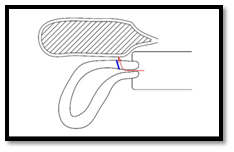

Another interesting finding of our study is the increased tendency of the CS group (although it did not reach a statistically significant level) towards having an adverse effect on embryo transfer procedure in IVF. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study focusing on the association between difficult transfer and a history of CS.In general, having full bladder may alleviate the embryo transfer if the uterus is anteverted (Figure 2a & 2b). But particularly when the uterus is retroverted, the outer sheath of the embryo transfer catheter may easily find its way through the repaired incision line (Figure 2c). This via falsa may create a great challenge for the clinician, sometimes difficult to overcome with curved and malleable catheters necessitating to do the embryo transfer under anesthesia and using instruments such as Hegar dilators, stylet and tenaculum. In two cases we failed to overcome the false route and we had to use tenaculum to straighten the cervical canal. The strengths of our study are: Studies in the existing literature are generally retrospective and population based in design which may have the shortcomings of a possible selection bias and interfering confounding factors; analysing the database of an IVF clinic distinguishes our study from the existing ones since the presenting couples are definitely diagnosed with secondary infertility fullfilling the waiting time criterion without any contraception method. This is a direct measure of fertility compared to follow up for parity or inter-pregnancy interval. In addition, so far almost all studies about the issue are from mid or Northern European countries and America. Our study is also unique as revealing the first data from more eastern region of the world. Last, ours is the first in the literature creating an attraction to the probable adverse effect of a prior caeseran on embryo transfer technique in IVF treatments.

Figure 2a Anteverted uterus with empty bladder (blue line: previous CS incision line; red arrow: route through the cervical canal).

Figure 2b Anteverted uterus with full bladder (blue line: previous CS incision line; red arrow: route through the cervical canal).

Figure 2c Retroverted uterus with full bladder (blue line: previous CS incision line; red arrow: route through the cervical canal).

The limitations of our study are the retrospective design and small sample size in both groups which decrease the statistical power. The increased tendency of the CS group for lower implantation rate and for difficult embryo transfer might reach a statistically significant level if the sample sizes would have been higher. Further studies with large sample sizes of comparable patient groups and appropriate acknowledgement of potential key confounders may help to come to a definite conclusion regarding the causal effect of CS on future fertility as well as on the embryo transfer procedure in IVF cycles. In conclusion, the association between CS and subsequent infertility must be taken into account by both the obstetrician and the pregnant patients and this association should enforce the practitioners to think twice before deciding for a CS and opt to proceed vaginal delivery as much as possible. The probability of encountering a difficult embryo transfer may also be a concern in case of IVF treatment.

None.

None.

©2017 Malabanan, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.