eISSN: 2377-4304

Research Article Volume 6 Issue 6

Department of Radiology, Vivantes Humboldt Hospital, Germany

Correspondence: Karsten Krger, Department of Radiology, Vivantes Humboldt Hospital, Am Nordgraben 213509 Berlin, Germany, Tel 49-30-130-12-3701

Received: March 20, 2017 | Published: May 3, 2017

Citation: Karsten KG, Lana G, Kai B, et al. Magnet Resonance Imaging in Preoperative Endometriosis: Incidence of High-Signal-Intensity Spots on Fat- Suppressed T1-Weighted and T2-Weighted Images. Obstet Gynecol Int J. 2017;6(6):162-165. DOI: 10.15406/ogij.2017.06.00227

Objectives: To investigate the incidence of high-signal-intensity lesions at preoperative T1 and T2-weighted magnet resonance imaging (MRI) in patients with pelvic endometriosis.

Study design: Between 2009 and 2012, 252 women with clinical and sonographic suspicion of endometriosis underwent pelvic MRI using T2 and unenhanced T1 sequences with and without fat saturation. Two radiologists interpreted the following regions retrospectively by consensus according to a standardized protocol: uterus, vagina, pouch of Douglas, rectum, uterosacral ligament (USL). High-signal-intensity lesions in the fat-suppressed T1-weighted images were defined as hemorrhagic foci. Their incidence and that of high-signal-intensity spots in T2-weighted images were documented in histopathological verified endometriosis.

Results: In patients with rectal endometriosis (128/252 patients), high-signal-intensity spots were detected on 10.2% of T1-weighted fat-suppressed images and on 16.9% of T2-weighted images. In uterus adenomyosis (236/252 patients) high-signal-intensity spots on T1 and T2 weighted images occurred in 43.2% and 24.2%, respectively (vagina (115/252, 31.3% and 41.9%; USL 119/252, 7.6% and 13.8%, pouch of Douglas 169/252, 31.4% and 28.1%, other localizations 7/252, 71.4% and 57.1%)

Conclusion: The incidence of high-signal-intensity spots on T1 and T2-weighted images depends on the localization of endometriosis. T1 und T2 high-signal-intensity spots are less relevant in diagnosing endometriosis of the rectum and uterosacral ligament.

SE, spin echo; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; USL, uuterosacral ligament; HE, hematoxylin-eosin staining

Endometriosis is characterized by endometriotic tissue consisting of hormone-dependent glandular formations, stromal cells and smooth muscle in sites located outside of the uterine cavity.1-6 The estimated prevalence of endometriosis is high and makes it to one of the most common pathologies in women of reproductive age.1,7-9

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is becoming a mainstay of pre operative diagnostics, in particular for diagnosing deep infiltrating endometriosis.10-17 MRI sensitivity and specificity depends on the localization of endometriosis.17 The most important technique for MRI uses T2-weighted and T1-weighted sequences. Hemorrhages within endometriotic foci are considered one hallmark feature of endometriosis distinguishable by MRI.18-21 According to the literature, the T1-weighted sequence with fat suppression improves the diagnostic value of MRI for endometriosis because it allows structures containing lipid to be differentiated from those containing blood.18-22 High-signal-intensity spots on the T1-weighted images count as characteristic features for detecting uterine adenomyosis in MRI diagnostics.23,24 In a recently published study on the value of MRI in the diagnosis of bladder endometriosis, high-signal-intensity spots were observed in 72% of all endometriotic foci.25 However, there are no data on the frequency of high-signal-intensity spots at fat-suppressed T1-weighted imaging in other localizations of pelvic endometriosis. In addition, typical findings in adenomyosis are high signal spots or strips in T2-weighted images.23,24 In bladder endometriosis, high-signal-intensity spots in T2-weighted sequences were detected in 61.1% of histologically verified endometriosis.25 No data are available on the frequency of T2 spots in other sites of localized pelvic endometriosis.

The objective of this study was to investigate the incidence of high-signal-intensity lesions at preoperative T1 and T2-weighted magnet resonance imaging (MRI) in patients with endometriosis at defined pelvic locations.

The study was approved by the institutional review board and carried out in accordance with The Code of Ethics of the Declaration of Helsinki. Prior to inclusion, the patients were presented with comprehensive information about the study. All patients gave their informed written consent to participate.

Patient population

During the period from 2009 to 2012, 252 women with clinical and sonographic findings suspicious of endometriosis underwent an MRI examination followed by laparoscopy involving surgical ablation of their endometriosis.

In all patients, medical history was taken followed by a clinical rectovaginal examination, transvaginal sonography and MRI. The surgical biopsies were histopathologically analyzed. All women had been examined according to our recently published MRI protocol.17 In brief, the examinations were performed on a 1.5 Tesla MRI (Magnetom, Avanto, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) using a 6-channel body coil without intravenous contrast medium. Transversal and sagittal T2-weighted and T1-weighted spin echo sequences with and without fat saturation were performed. Immediately before the examination, 200 ml of water were administered rectally, 10 ml of sterile gel (Instillagel, Farco-Pharma, Cologne, Germany) vaginally and 20 mg of butylscopolamine (Buscopan, Boehringer Ingelheim, Germany) intravenously. An optimal filling status of the bladder was achieved as recently described.25 In all patients, the examinations were performed outside of the menstrual phase.26 The inclusion and exclusion criteria were described recently.17 Two MRI-experienced radiologists evaluated the scans by consensus. The MRI studies were evaluated on a work station approved for the review of radiological images (monitor: EIZO, Eizo Nanao Corporation, Hakui, Japan; PACS: Impax, AGFA Health Care, Bonn, Germany). In conducting the study, patient data were pseudonymized by replacing the patient’s name with a number.

Surgery

The surgical technique was recently described in detail.17 In short, all patients underwent a preoperative MRI of the pelvis, a transvaginal and transrectal ultrasound and a rectoscopy. Laparoscopies were performed by an experienced gynecological endoscopist. Inspection covered the cecum and appendix region, ascending colon, right medial and epigastric peritoneum, right diaphragmatic dome, right liver region and gastric curvature and extended to the left diaphragmatic dome, left hepatic region, spleen and the left medial and epigastric peritoneum, the intestinal folds and omentum. After placing the patient in a maximum head-down Trendelenburg position, the entire pelvic peritoneum was scrutinized. Next, the standardized examination was performed of the round ligaments, bladder peritoneum, tubes, ovaries, ovarian fossae, uterosacral ligaments, pouch of Douglas and uterus. Finally, the foci were resected one-by-one and subjected to histopathological examination. The staging of endometriosis was characterized using the Classification of the ASRM and the ENZIAN classification for deep infiltrating endometriosis.27

Pathology

As previously described in detail,17 the surgically resected lesions were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) for histopathologic studies. Diagnosis of endometriosis was based on proof of ectopic endometrial glands and stroma in the resected lesions.28 In all cases, the presence of estrogen and progesterone receptors and KI 67 (kiel) was verified.29 Histopathological verification of endometriosis was classified as a positive finding.

Statistics

If not otherwise stated, the numbers are expressed as means ± standard deviations or percentages. Laparoscopy with histological verification of the diagnosis for endometriosis was used as the gold standard. In Adenomyosis, medical history, uterine ultrasound and endoscopic criteria such as serositis, ischemic areals, and changes in muscular consistence confirmed the surgical diagnosis of endometriosis genitalis interna.

Uterus

A denomyosis was correctly diagnosed by MRI in 236 of 252 patients (93.6%). Of the patients with positive finding of adenomyosis 102 patients (43.2%) had high-signal-intensity spots in T1 weighted images with fat suppression within the lesion. High signal spots or stripes in T2 weighted images with in the lesion were detected in 24.2% of the patients

Vagina

MRI finding of vaginal endometriosis was correctly diagnosed in 115 of the 252 patients (46.6%).. In 31.3% of manifestations with a correct positive diagnosis on the MRI, high signal intensities were observed in the fat-suppressed T1 SE sequence. High-signal-intensity spots in T2 weighted imaging were detected in 41.9%.

Rectum

A MRI positive finding of rectum endometriosis was proved by histopahology in 128 of the 252 patients (50.8%). In 13 patients (10.2%) with histopathology proven endometriosis of the rectum high signal intensities were observed in the fat-suppressed T1 SE sequence and in 19.6% high signal spots in T2 weighted imaging, (Figures 1-3).

Figure 1 40-year-old woman with primary dysmenorrhea and dyspareunia in endometriosis stage rASRM II°. Rectal endometriosis with high signal intensity spots on T2-weighted spin echo images (arrow in a) but without any bright spots on T1 weighted images with fat suppression (b).

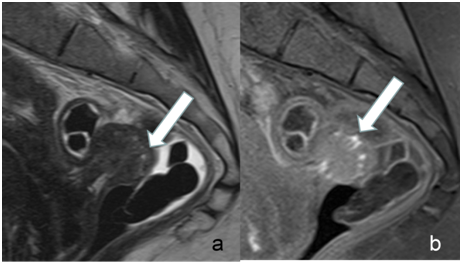

Figure 2 Example for rectal endometriosis in a 35-year-old woman. Many high signal intensity spots were detectable on both, T1 weighted images with fat suppression (arrow in b) and on T2 weighted images (arrow in a).

Figure 3 39-year-old woman with endometriosis stage rASRM II°. MRI demonstrates rectal endometriosis with only a few high signal intensity spots on T1 weighted images with fat suppression (b). On T2 weighted images (a) the endometriotic lesion shows a low signal intensity but without high signal spots.

Uterosacral ligaments

In 47.2% (119 of 252) of the patients, endometriotic implants were histopathologically proved in the uterosacral ligaments. In 9 patients (7.6%) of manifestations with a correct positive diagnosis on the MRI, high signal intensities were observed in the fat-suppressed T1 SE sequence. In T2 weighted images high-signal-intensity spots were observed in 13.8%

Pouch of Douglas

In 169 patients (67.1%) the MRI finding of endometriotic lesion in the pouch of Douglas was proved. Of these patients high-signal-intensity spots in T1 weighted fat suppressed sequences were observed in 53 endometriotic lesions (31.4%) and T2 weighted spots in 28.1%.

Other manifestations

In 7 of the 252 patients (2.8%), endometriotic implants were found at the following locations: abdominal wall in 5 and in the groin in 1 and at vaginal introitus one. In 5 of 7 manifestations on the MRI image (71.4%), high signal intensities were observed in the fat-suppressed T1 SE sequence. High-signal-intensity spots were observed in 57.1% in T2 weighted images

MRI ranks as one of the main stays for diagnosing endometriosis. This study tried to further evaluated characteristics of endometriosis in MRI. According to the literature, the T1-weighted sequence with fat suppression improves the diagnostic value of MRI18-22 because this sequence enables a differentiation between structures containing lipid and those containing blood. Endometriotic lesions typically appear with low signal intensity on T2 weighted images. They are further characterized by high-signal-intensity spots in the fat-suppressed T1-weighted sequence. In a recently published study on bladder endometriosis high-signal-intensity spots were found in 72% of all endometriotic lesions.25 Also for uterine adenomyosis high-signal-intensity spots in the T1 -weighted in MRI were found as a typical finding.23,24 These spots are the result of hemorrhages and count as characteristic features in MRI diagnostics.18-21 The T1-weighted sequence with fat suppression are said to improve the diagnostic value of MRI for endometriosis because this sequence allows for structures containing lipid to be differentiated from those containing blood.18-22

However, so far there are no data about the frequency of high signal T1-weighted spots in different localizations of pelvic endometriosis. In our study, we investigated a large patient group of histologically proved endometriosis and positive findings in MRI at different localizations. Interestingly, the frequency of high-signal-intensity spots in our patient population was very variable. It was lowest in endometriotic lesions of the uterosacral ligaments (8%), followed by rectal endometriosis (10%), the endometriosis of the vagina and the pouch of douglas (both with 31%) and the uterus with 43%. The frequency of high-signal-intensity spots was remarkable lower than in the recently published data on bladder endometriosis. Obviously, bleeding in the endometriotic lesions occurs with different frequency. We only can speculate about the reasons why these differences occur. One possible reason could be the activity and the duration of the disease.

In our patient population, endometriosis at other locations was rare. However hemorrhagic foci were observed at a very high frequency of 71%. We did not provide data about the frequency of high-signal-intensity spots in T1 for ovarian and peritoneal endometriosis because for both this is a very typical or even the only feature in MRI and reaches 100%. For ovarian endometriosis one should keep in mind that we have morphological criteria like thickening of an ovarian cyst wall, reactions in the surrounding tissue, the so called “dark clot sign”30 and the markedly lower apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) in endometriomas than in functional ovarian cysts which can improve the specificity of MRI.31 Peritoneal manifestations are only detected by MRI if they contain blood. Therefore, T1 high-signal-intensity spots are very important to detect peritoneal endometriosis. However, by no means do all peritoneal endometriotic implants feature hemorrhagic foci. These are the pigmented and black clusters containing hemosiderin-laden macrophages. Only these are detectable in the fat-suppressed T1 SE sequence.19 For this reason, MRI has a low sensitivity in the diagnostic of peritoneal endometriosis and plays not an important role in this part of the disease.17

Another feature of endometriosis in MRI are high-signal-intensity spots in T2 weighted images. These were observed in 61% in bladder endometriosis25 and are characteristic features in MRI diagnostics for uterine adenomyosis.23,24 In our study on other localization we found high-signal-intensity spots in a frequency between 14% for endometriosis of the uterosacral ligaments and 42% for endometriosis of the vagina. As with high signal T1, the frequency of high-signal-intensity T2 lesions is very variable.

One limitation of this study was its retrospective design. We interpreted the high-signal-intensity lesions in fat saturated T1 images as hemorrhagic foci as in the literature,18-21 but this was not correlated with histopathology.

The data of our study show that the relevance of the fat-saturated T1 sequence and T2 spots for diagnosing endometriosis varies, depending on its location. T1 und T2 high-signal-intensity spots are less relevant in diagnosing endometriosis of the rectum and uterosacral ligaments.

None.

None.

©2017 Karsten, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.