eISSN: 2377-4304

Case Report Volume 6 Issue 4

1Department of O&G, KK Womens and Childrens Hospital, Singapore

2Department of O&G, KK Womens and Childrens Hospital, Singapore

3Minimally Invasive Unit, KK Womens and Childrens Hospital, Singapore

4Department of Urogynaecology, KK Womens and Childrens Hospital, Singapore

Correspondence: Weng Yan Ho, Department of O&G, KK Women's and Children's Hospital, 100 Bukit Timah Road, Singapore 229899, Singapore, Tel 65-98639852, Fax 65-62918135

Received: January 29, 2017 | Published: March 23, 2017

Citation: Weng YH, Candice W, Sze CH, et al. Spontaneous Uterine Rupture in the Second Trimester: A Case Report. Obstet Gynecol Int J. 2017;6(4):84-87. DOI: 10.15406/ogij.2017.06.00211

We report a case of spontaneous uterine rupture at 17+6 week’s gestation in a nulliparous 32 year old patient with no history of myometrial surgery. She had presented with lower abdominal discomfort, progressing to severe pain with hypotension and tachycardia. An urgent ultrasound pelvis showed a live fetus with fetal tachycardia, free intra-peritoneal fluid with blood clots and myometrial defects on the uterine fundus. An emergency laparotomy performed revealed 1.7 liters of hemoperitoneum, with the fetus intact in the amniotic sac free floating in the peritoneal cavity. The uterine fundal rupture was successfully repaired. Placenta histology revealed placenta accreta. This case report demonstrates that a high index of suspicion, rapid diagnosis aided by imaging modalities and immediate surgical intervention are crucial steps in successful management. A postulated etiology in our patient is that of an upper scar from a previous uterine curettage with abnormal placentation predisposing to spontaneous rupture.

Keywords: Spontaneous uterine rupture, Second trimester, Placenta accreta, Fetus, Hemoglobin, Percreta, Diagnosis, Hemostasis, Increta

Spontaneous uterine rupture before onset of labour is extremely rare. This is even more so in the second trimester of pregnancy, in nulliparous women and in the absence of myometrial surgery.1 The initial presentation of this potentially catastrophic event may be non-specific, with upper or lower abdominal discomfort, vague gastrointestinal or urinary symptoms preceding rapid deterioration.2 A high clinical index of suspicion with the judicious use of imaging modalities if promptly available may assist in establishing the diagnosis, enabling immediate surgical intervention. We present an unusual case of spontaneous uterine rupture at 17+6 weeks’ gestation, the first of its kind to be reported in Southeast Asia.

A 33 year old Chinese female, gravida 2 Para 0, at 17+6 weeks gestation presented with severe lower abdominal pain and abdominal distension. The patient’s past history included an evacuation of uterus at 7 weeks gestation for a miscarriage 1 year ago. The evacuation of uterus was carried out uneventfully with no apparent surgical complications. There was no other history of prior uterine surgery. There was no precipitating event such as trauma sustained. The patient had received regular antenatal care at the hospital since 8 weeks gestation and her pregnancy had been uncomplicated thus far. Three days earlier, the patient had complained of suprapubic pain associated with mild dysuria and was treated empirically for a presumed urinary tract infection. She was discharged home well.

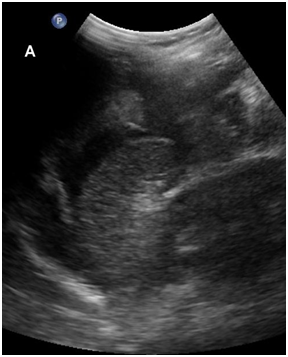

On examination, the patient’s temperature was 36.8 0C, blood pressure was 78/55mmHg, heart rate was 115 beats per minute. There were signs of acute abdomen with diffuse tenderness noted over the abdomen with guarding. On speculum examination, the cervical os was closed and there was no per vaginal bleeding. The patient was stabilized and fluid resuscitation immediately commenced. Urgent blood investigations sent off showed a full blood count with hemoglobin of 10.4g/dL and a total white cell count of 21.9 x 109/L. Urgent sonographic imaging showed an intrauterine live fetus with fetal tachycardia and irregular heart rate. There was intra-peritoneal free fluid and blood clots seen, indicative of hemoperitoneum (Figure 1). The uterine myometrium appeared discontinuous at the fundus, suggestive of uterine rupture (Figure 2). An i-STAT finger print blood count subsequently done showed a hemoglobin level of 5.8g/dL and packed red blood cell transfusion was immediately commenced. The patient was sent to the women’s intensive care unit and preparation for emergency laparotomy was initiated.

Figure 1 Trans-abdominal ultrasonography, longitudinal view of the abdomen (5 MHz curved transducer, Philips iU22) demonstrating intra-peritoneal anechoic free fluid and heterogenous hyperechoic structures in the peritoneal cavity, likely representing blood clots.

Figure 2 Trans-abdominal ultrasonography, transverse view of the uterus (12 MHz linear transducer, Philips iU22, A) and (5 MHz curved transducer, Philips iU22, B) demonstrate defect in the myometrium (arrow).

Under general anaesthesia, emergency laparotomy was performed via a pfannenstiel incision. 1.7 liters of hemoperitoneum, mostly in clots, was evacuated. The intra-operative finding was that of the fetus intact in the amniotic sac free floating in the peritoneal cavity (Figure 3). The rupture site was identified and found to be located at the fundus of the uterus (Figure 4). The placenta was found to be located fundally, at the site of the uterine rupture. There was no other significant abnormality or deformity of the uterus. Bilateral fallopian tubes and ovaries appeared healthy and normal. The gestation sac, fetus and plcaenta were removed and blunt curettage of the cavity was performed. The uterine defect was closed with 0 polyglactin 910 (VicylTM) sutures in 2 layers. The fetus weighed 224g and the placenta weighed 110g. The placenta was sent to the pathology lab for histological examination. A total of 5 units of packed red blood cell and 2 units of fresh frozen plasma were transfused. The patient was monitored in the intensive care unit for 12 hours and the high dependency unit for the next 48 hours. She was discharged home well on the 5th post-operative day.

Figure 3 Fetus in amniotic sac free floating in peritoneal cavity encountered during emergency laparotomy.

Histopathological examination of the placenta showed areas of chorionic villi directly abutting the myometrium without intervening decidua. This was demonstrated by dual-labelling immunohistochemical staining for cytokeratin AE1/3 and smooth muscle actin, indicating placenta accreta. The fragmentation of the specimen however had precluded assessment for placenta increta or percreta.

Spontaneous uterine rupture in the second trimester of pregnancy without prior uterine surgery is rare. Reported cases in the literature suggest underlying etiologies of abnormal placenta implantation3-9 and congenital uterine abnormalities such as bicornuate uterus10 and uterine septum.2 Occasionally, no underlying cause is found.11-13 The cases are summarized in Table 1.

|

Author |

Year |

Country |

Age |

Gravida/para |

Gestation |

Presenting symptoms |

Treatment |

Risk factor |

|

Faguer C et al.3 |

1988 |

France |

? |

3/2 |

22 weeks |

Abdominal Pain |

Hysterectomy |

Placenta increta which had grown in the fundus which contained a fibroid |

|

Nagy et al.4 |

1989 |

Hungary |

21 |

1/0 |

23 weeks |

Abdominal Pain |

Primary Closure |

Placenta percreta |

|

Job et al.5 |

1994 |

Germany |

? |

1/0 |

22 weeks |

Abdominal Pain |

? |

Placenta percreta |

|

Kinoshita et al.6 |

1996 |

Japan |

30 |

1/0 |

25 weeks |

Abdominal Pain |

Subtotal Hysterectomy |

Placenta percreta |

|

Imseis et al.7 |

1998 |

USA |

23 |

1/0 |

26 weeks |

Abdominal pain, severe hypotension, tachycardia, fetal heart rate decelerations |

Hysterectomy |

Placenta percreta |

|

Wang PH et al.11 |

1999 |

Taiwan |

31 |

1/0 |

21 weeks |

Abdominal pain, Hypotension, Tachycardia, fever |

Primary repair of cornual rupture |

Nil |

|

Chen FP et al.12 |

2007 |

Taiwan |

29 |

1/0 |

26 weeks |

Abdominal pain, upper gastrointestinal tract symptoms |

Primary repair of fundal rupture |

Nil |

|

Ansar et al.8 |

2009 |

Pakistan |

20 |

1/0 |

17 weeks |

Abdominal pain |

Primary closure |

Placenta percreta |

|

Agu et al.10 |

2012 |

Nigeria |

25 |

1/0 |

25 weeks |

Abdominal pain |

Excision of ruptured left horn and closure of defect |

Bicornuate uterus |

|

Gianluca et al.2 |

2012 |

Italy |

30 |

1/0 |

23 weeks |

Abdominal pain |

Primary repair |

Septate uterus |

|

Sun HD et al.13 |

2012 |

Taiwan |

? |

3/2a |

17 weeks |

Upper abdominal discomfort, vomiting |

? |

Nil |

|

Peirzynski et al.9 |

2012 |

Poland |

35 |

5/5 |

15 weeks |

Abdominal pain, hypovolemic shock |

Subtotal hysterectomy |

Placenta percreta |

Table 1 Summary of Uterine Ruptures in the Second Trimester in Women without Previous Uterine Surgery

In our patient, a postulated etiology for the spontaneous uterine rupture might be that of abnormal placenta implantation, possibly placenta accrete/percreta from uterine scarring from her previous evacuation of uterus. In placenta percreta, the decidua basalis is partially or completely absent, and the chorionic villi invade the entire myometrium up to the serosa. Uterine rupture caused by placenta percreta mainly occurs in the later part of pregnancy, with few reports occurring in the first and second trimesters. Many have a significant history of prior uterine surgery such as caesarean section or myomectomy. The earliest reported case occurred at 9 weeks gestation.14

Spontaneous uterine rupture in early pregnancy poses a diagnostic challenge, as initial symptoms may be vague and non-specific. The onset of abdominal pain may begin hours and even days prior to the diagnosis of uterine rupture. In the absence of a scar from previous surgery, clinical suspicion of uterine rupture in early pregnancy may be further lowered. As in the case of our patient, urinary tract or gastrointestinal tract symptoms may be present as well, serving as red herrings that prompt considerations and empirical treatment for other causes of abdominal pain in pregnancy. These include infective causes such as gastroenteritis and urinary tract infection, or surgical causes such as appendicitis.

The role of ultrasound in the diagnosis of spontaneous second trimester ruptures has been reviewed by a cohort study.1 In institutions with rapid access to sonography services, ultrasound may be considered as a tool in patients who are hemodynamically stable to support or establish the diagnosis. Importantly, the scan findings have to be interpreted and taken in context with clinical findings as well. In first trimester uterine ruptures, laparoscopy has been reported as a tool for the investigation of acute abdomen with unclear diagnosis.15 To our knowledge, there has been no study done to date about the use of laparoscopy for second trimester uterine ruptures.

Emergency laparotomy with extraction of the fetus and hemostasis is the cornerstone of treatment. Hemostasis may be achieved with either primary repair of the defect or hysterectomy if the bleeding could not be adequately controlled. Successful continuation of the pregnancy had only been reported in 2 instances;11,12 in both cases, the defect was small and the fetus remained in-utero. There was primary repair of the small defects at emergency laparotomy with tocolysis commenced. Delivery occurred at 33 and 37 weeks respectively via caesarean sections. In both cases, no apparent cause was found for the spontaneous second trimester ruptures.

In conclusion, this report highlights the significance of a history of evacuation of uterus predisposing to abnormal placenta implantation and spontaneous early pregnancy uterine rupture. Despite the gestation, in women presenting with symptoms and signs suggestive of acute abdomen and hemodynamic instability, prompt resuscitation must be instituted, and a high index of suspicion for rupture must be suspected. Ultrasound is a useful tool to aid in establishing the diagnosis even in early pregnancy and should be considered if the facility is rapidly available.

We would like to thank Dr. Ehab Shaban Mahmoud Hamouda for his kind contribution of the ultrasound scan images and descriptions.

None.

©2017 Weng, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.