Open Access Journal of

eISSN: 2575-9086

Review Article Volume 7 Issue 1

Casa de Altos Estudios “Don Fernando Ortiz” Universidad de La Habana, Cuba

Correspondence: Yaimara Izaguirre Martí, Casa de Altos Estudios “Don Fernando Ortiz” Universidad de La Habana, Cuba

Received: February 28, 2024 | Published: April 1, 2024

Citation: Martí YI. Emancipated women in Cuba: strategies of freedom and motherhood inside of the conflict. Open Access J Sci. 2024;7(1):84-93. DOI: 10.15406/oajs.2024.07.00218

In 1878, the brunette Mariana Bravo,1 single, a native of Africa, 30 years old, a cook by trade and in the service of Don Luciano Bravo for more than two decades, she appeared before the Lieutenant Governor of the city of Trinidad demanding her letter of freedom. According to her, she considered herself to be of the emancipated class.2 The fundamental purpose of her claim was to use the institutional channel to achieve recognition of her legal status, which would bring her freedom and the possibility of being hired as a free worker.3

The journey towards its goal began on June 21, 1878 with its entry, as a deposit, into the Casa de Beneficencia. The city's Inspector of Surveillance and Public Security House also had to name two witnesses for assistance. For this case, Don Benito Besada and Don Agustín Romero, both of legal age and residents of the city, were chosen. The designation of said witnesses and the Surveillance Inspector was the first step to initiate any claim process.

In accordance with the provisions of the law, certain issues had to be clarified in the lawsuit initiated by Mariana. For example: with respect to the slave expedition in which he had arrived on the Island, he had to specify the name of the captain of the expedition ship, the place where the disembarkation took place and its date, and the date on which the Government Superior of the Island had declared the expedition exempt from its dependence.

At the same time, Mariana had to explain, in addition to the questions already mentioned, others such as: the number with which she was assigned, make known the names of some of the companions of her expedition, the name of the consignee or employer to whom she had been consigned. once the sentence of her capture was handed down, the reasons why the consignee did not comply with the resolution of freedom, as well as the existence of a possible contract between the employer and Mariana - if she had been released - and the reasons why which the emancipated woman had not been presented to the Government by her consignee.4

From a formal point of view, the procedure included: the preparation of the minutes which reflected: the instance of the claim, the day and time of the case and the prior summons to the consignees; the oath of fidelity in the statements of witnesses, instructors, emancipated persons and employers; the presentation of all documents related to the consignment; the process of statements from all possible parties, to gather all possible evidence and finally, the recognition of affiliation and other particular characteristics.

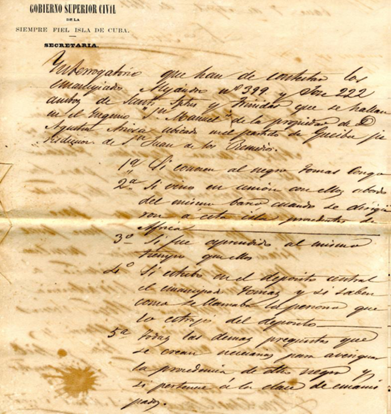

Mariana Bravo was interrogated in a trial that lasted almost 3 months. The delay of the processes depended, on many occasions, on the delay in the presentation of the documents that were in the hands of the consignees. These, in general, did not reside in the same places, sometimes they were outside the Island and some had even died and the documentation was in the hands of their guardians. On the other hand, transfers of emancipated people were carried out without the prior knowledge of the Government Image 1.

Image 1 Fragment of interrogation of an emancipated person.

Fountain: National Archive of Cuba, Havana (ANC), Miscellaneous Files, leg. 3656, no. Co. File formed to clarify the numbers and origins of the emancipated people returned by Mrs. Juana Izaguirre de Lombil, named Tomas and Francisco. Havana, February 1867.

Some of the questions asked during the interrogations referred to issues that enslaved Africans generally could not always answer, especially those referring to slave expeditions. However, Mariana's statements revealed a relatively informed woman, aware of her possibilities and that she fell within the legal framework to make use of her rights. For example, she pointed out that “…. She had landed with the name of Lemba and that when she was baptized, in the Mayor parish of the city by her godmother Doña Josefa Mendoza, they gave her the name Mariana. He also knew “... that the dark-skinned Constanza Picayo is in the city...”,5 of the same condition as her and has news that “…. “A countryman, Pio Echemendía, is in the Casilda district, and this may give rise to the name of the expedition in which we came….”

His statements denote the opportunities that the urban environment offered to the enslaved and free, as well as to the emancipated. They could go around the city, talk, listen and have connections with other people. Among them, with those who came from the same place or on the same boat, who, on more than one occasion, were united under ties of friendship and some other types of emotional ties that Africans and their descendants could create to live in slavery.

The place where they worked was another space that provided them with opportunities to acquire legal information. In this case, the house where she worked as a cook was conducive to creating a beneficial relationship not only with her consignee, but with other members of the family and members of the servants. The possibilities of information, mobility, integration with other social strata allowed Mariana to acquire the necessary legal rudiments to accuse her consignee and use the law for her own benefit. Hence, on Mariana's part, she herself expresses: "... that for her to be given her letter of freedom since others of her companions already have it...

To clarify the fact that was being processed, several people were called to give statements in the process. The first was Don Pablo Bravo—legal representative of his father Don Luciano Bravo—a native of Trinidad, of single status and owner by profession. He said that the brunette had been purchased for 500 pesos, but that there was no document proving it because it had been acquired in good faith. He also declared that he had no objection to being granted his right to emancipation even though he had only recently been aware of this issue for 2 months. The behavior of the employers was not always opposed to the claims of the emancipated. One group used the possibility of freedom to stimulate the work and dedication of its consignees.

The free Africans Constanza and Pio - both of free status - had to give statements under oath. Both agreed on the facts of having known Mariana for 16 to 18 years, for having been a companion on the same expedition in which they arrived to the Island, although they did not know the name of the ship, but according to what they had heard it was the expedition of Casilda.

The legal actions presented by the emancipated had to be verified in the filiation records and not only by the testimonies of trustees, assistance witnesses or inspectors, plaintiff and other declarants. The filiation document was essential for these processes, because after each capture, the Political Secretariat had to create a record for each captured muzzle, which must reflect the name, the vessel, the number of the expedition to which it belonged, particular signs of his body, such as the scarifications of his cultures of origin, or those produced by the carimbo and the consignee to whom he had been assigned.

In the case of the brunette Mariana, her status as emancipated could not be officially declared because the name “Lemba” did not appear in the list of muzzles captured in the “Casilda” expedition that existed in the archive of the Political Secretariat. With the cache captured on the island known as “Casilda” - a port in the Trinidad area - 70 were declared emancipated - according to Dr. Inés Roldán's database - and placed at the disposal of the local authorities. However, this case is exceptional because the statements of Pio, Constanza, the parish priest, and the mother of the now deceased baptismal godmother influenced the case to be sealed with a resolution that declared Mariana muzzled and emancipated and the manumission letter will be delivered to you by the consignee.

Beyond the description of this claim process, Mariana's request involves a group of complex issues around the study of legal claims developed by emancipated women in Cuba. Through the analysis of the demands promoted from the Royal Decree of 1856 that legally established the right of the emancipated to be defended by the Trustees of the City Councils in conciliation and verbal trials, and the fiscal promoters and the Prosecutor of SMC would do so in written trials before judges and ordinary courts1 until the date of 1880 when information was found in the sources consulted for this research, the article contributes to the debate of women, in her double status as woman and mother, for her own emancipation and that of her children. Hence, I analyze the forms of interaction with the legal corpus based on the recognition that emancipated women had of their particular condition and their rights, especially maternal. At the same time, it reveals how in this context of legal support, fostered by a group of conditions that introduced institutional and attitudinal changes, the legal and social meaning of motherhood in the Cuban slave society gains voice.

This text will also approach the causes, difficulties, sentences and actions of other figures involved in the procedures of these processes through some of the life experiences collected in the personal stories told in the ANC files. It is necessary to point out that this reconstruction was extremely complex since it is known that emancipated people, slaves, embargoed people, barely left written testimonies and their activities exceptionally appear recorded in the public sphere. From these it will be possible to know the beginning of new practices around women such as transfers or returns.

The contributions that have been made to the topic of legal strategies of the group of emancipated people have been made in Brazil and Spain. For their part, in Cuban historiography, the emancipated have occupied a limited space. There were emancipated people in several regions of the Caribbean, however, the majority settled in Brazil and Cuba. The recent Brazilian historiographic production has made it possible for several spaces of the existence of this social group, in diverse regional and social spaces, to be known. Among these, Cyra Luciana Ribeiro de Oliveira stands out: Os Africanos livres em Pernambuco, 1831-1864.6 The author exposes the reasons why the condition of the emancipated is similar to that of slaves, at the same time, like these They were aware of their condition and fought through various “practices of resistance” for diversified treatment before the authorities and courts.

In Cuban historiography, some of the generalizations regarding the legal context of the birth of the emancipated have been taken up and new perspectives have been provided, such as the approach to the articulation of various businesses around the emancipated under the intervention of recognized personalities directly dedicated to the slave trade and the framework developed by the Captains General to guide local provisions and international policies for their benefit. Such is the case of the text by Cuban historian Juan Pérez de la Riva in his book: The reserved correspondence of General Don Miguel Tacón with the government of Madrid (1934-1936).7

Within contemporary Spanish historiography, the researcher at the Institute of History of the CSIC Inés Roldán de Montaud, in her bachelor's thesis titled: The social condition of emancipated blacks in Cuba (1817-1870),8 is interested in building a general vision of the group of emancipated people, which shows the importance of the topic at an international level. Its text, later edited in the form of an article, constitutes the fundamental reference for the analysis of the group's presence in Cuban society and the problems that this caused. Dr. Roldán's work analyzes the factors that degraded the condition of the emancipated; however, she states in her text that her research could not deal in any detail with the awareness that the emancipated had of their legal condition, due to the administrative nature of the main sources. that he used, deposited in the National Historical Archive of Madrid (AHN).

The study of the legal actions or claims processes undertaken by the liberated Africans was carried out based on case studies that do not constitute a sample, since the universe of the emancipated is not yet known. Below we present a Table 1 where the different legal claims made by them based on their sex are noted.

|

Claims |

||||||

|

Years for five years |

Test condition |

Request for letters of Freedom |

Complaints |

|||

|

Men |

Women |

Men |

Women |

Men |

Women |

|

|

1861-1866 |

7 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

|

|

1867-1870 |

15 |

5 |

30 |

21 |

83 |

38 |

|

1871-1876 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

||

|

1877-1880 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

4 |

1 |

|

|

Totals |

25 |

10 |

31 |

25 |

88 |

42 |

Table 1 Legal claims of emancipated people by sex (1856-1880)

Source: Database created by the author from the files of claims processes undertaken by the emancipated from the National Archive of Cuba of the Miscellaneous Files Fund.

Of a total of 221 claims studied in the period, men were the ones who approached the courts the most, 144 were carried out by men (65%) and 77 by women (35%). It should be noted that the number of men introduced in relation to the number of women was always greater, also that the benefits of having men enrolled is an important element. However, the presence of women in this study must be highlighted, as their resistance to the cruelest oppression, exploitation and mistreatment received is evident once again. But, furthermore, I would like to highlight that approximately 10% of these mothers. (use verb in past)

The claims that this text will address are framed between 1856-1880. It is not possible to assert that there were only legal actions by emancipated people on the dates for which information has been found in the sources consulted. The essence of this study period is the establishment of regulations for these processes, taking into account international treaties, but above all based on the legislation regulated by the Captain General of the Island.

1National Archive of Cuba, Havana (ANC), Miscellany of Files, leg. 3642, no. H. Prepared file of order of the Sr. Colonel Lieutenant Governor in investigation of whether the emancipated black woman Mariana Bravo corresponds to the class of emancipated, according to the same statement in the application presented to the aforementioned Superior Authority. Trinity, 1878.

2On September 23, 1817, a treaty was signed with the government of Madrid that marked the transition from simple debt, stipulated in 1814 in Vienna, to prohibition. In this new agreement, Spanish subjects are prohibited from dealing with the slave trade, immediately to the north of the Ecuador, leaving a period of six months for the expeditions begun to conclude their journeys, and allowing their continuation to the south of the Ecuador, until the May 30, 1820. The agreement also implied the commitment to deliver a certificate of emancipation in favor of the Africans who were on board. This situation caused the legal birth of the emancipated people in Cuba, which was specifically born in 1824 with the capture of the first brig. There were emancipated people in several European countries dependent on colonial metropolises, but the majority settled in Sierra Leone, Brazil and Cuba; although a significant segment of those liberated by the Mixed Commission in Havana went to Jamaica, Trinidad and Belize. In the case of Cuba, no certificate of emancipation has been found in the National Archives; apparently the document that replaces it is the document known as Filiation of signs particulars, delivered at the time of the sentence and in which the name, vessel and number of the expedition to which it belonged, consignee and other personal details of the body.

3The study of the legal actions or claims processes undertaken by the emancipated in Cuba is part of the project of the Slavery Studies Group in Cuba, which is based in the Don Fernando Ortiz House of Higher Studies of the University of Havana and forms part of the 2nd chapter of my master's thesis: The legal actions of the emancipated in Cuba (1824 - 1886) (Unpublished). In this way, we worked with: Files to prove emancipated status, Files requesting letters of freedom, Files for complaints against the consignees. In this work, the various actions of the emancipated people will be examined with the support of a set of indicators such as: the labor context in which the emancipated people who came to court were inserted, the dissimilar alliances formed, the time spent on the Island, the time elapsed from the beginning of the process to the sentencing, and ultimately, the results of the different claims processes.

4The consignees of the emancipated were constituted by the institutions, corporations or private persons that received them, by delivery of the Superior Civil Government - Political Secretariat - with the purpose that through a period of learning - of 5 to 7 years depending on being an adult, a woman or child - were to instruct them in the dogmas of the Catholic religion and teach them some trade or mechanical art. They had to pay compensation to the Government.

5National Archive of Cuba, Havana (ANC), Miscellany of Files, leg. 3642, no. H. Investigation of whether the emancipated black woman Mariana Bravo corresponds to the class of emancipated, according to the same statement in the application presented to the aforementioned Superior Authority. Trinity, 1878.

6Ribeiro de Oliveira, Cyra Luciana. The African books in Pernambuco, 1831-1864. Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, 2010. (Master's Thesis).

7Pérez de la Riva, Juan. The reserved correspondence of General Don Miguel Tacón with the government of Madrid (1934-1936). National Council of Culture. José Martí National Library, Cuban Collection Department, Havana, 1963.

8Roland de Montaud, Inés. The social condition of emancipated blacks in Cuba 1817/1870. Complutense University, Faculty of Geography and History, Contemporary History Section, Madrid, 1980. (Bachelor Thesis).

The term "emancipated" was born in the context of the campaign for the abolition of the Atlantic slave trade. It applied to all Africans who were found on ships involved in illegal trafficking and who were apprehended at sea or taken ashore. The condition of this new legal subject was that of a legally free individual, in application of the international treaties that prohibited the slave trade, signed between Spain and England in 1817 and 1835.9 In this regard, the Captain General of the Island of Cuba José Gutiérrez de la Concha stated:

That fear that, looking at the number alone, could seem exaggerated, would turn out to be fair and founded when considering that the class of emancipated people, a class imbued from the moment they entered the Island with the idea that they are entirely free, and who therefore suffers with more impatience the position temporary imposed by the regulations, is at the same time the least moralized because they lack an owner, who, even out of interest and fear of losing the capital employed in them, monitors them and guides them towards good.10

These ships were judged by Mixed Commissions established in Havana and Sierra Leone, and in charge of deciding on the legality of the captured prey, without possible appeal. These institutions had to deliver a certificate of emancipation and the corresponding Government is obliged to guarantee the freedom of those subjects.

The regulations for the emancipated always tried to implement measures aimed at establishing good treatment and preventing their reduction to slavery, but these provisions were violated in practice. Around them, actions such as concealment, plagiarism and transfers were instituted, in addition to being included in those common behaviors of the slave society such as buying, selling and renting. This meant that their condition was worse than that of the slave, as David Turnbull recognized at the time: “(…) the condition of the emancipated at the Havana is worse than ordinary slavery.”11

The emancipated lacked the legal rights established for slaves and a legal institution or person to defend them, at least in the first half of the 19th century. However, some tried to appeal to the methods of manumission or coarctation, without being attended to, since that right did not legally correspond to them. Others struggled to be recognized for their legal status and to achieve specific treatment through the court claims processes.

From the appearance of the category of emancipated, from the treaties condemning the slave trade, until its disappearance, a group of actions, strategies and provisions emerged, including legal institutions to regulate the life of the emancipated on the Island. Within In this group of regularizations, the Captains General paid great interest to aspects related to the consignment system, the treatment that the emancipated should receive, the new institutional control that emerged and, above all, the granting of letters of freedom. At the same time, in practice, said legislation did not reflect the spirit of the agreement that gave birth to this group.

Regarding the maternal bond between emancipated women and their children, the right of the emancipated black woman to care for her children was recognized in the regulations. The first legislation promulgated by the colonial authorities that govern the life of the emancipated on the Island is the Conditions of Distribution of Captain General Don Dionisio Vives, in which it is established that they would be consigned for an apprenticeship period of 5 years for the great and 7 for children and females who had a child unable to work. Which is important, especially for the final decades in which the demographic data of the group varies since the number of children and women increases to the detriment of the number of men with respect to the initial years. Vives' conditions that were intended to be transitory in 1825 were extended until the group's legal disappearance.

However, since the capture of the first brig, in the waters of the Island in 1824 until 1856, a set of factors existed that prevented the undertaking of claims processes so that they could claim certain rights included in legislation that sought humane treatment of slaves but that in practice they were violated. Hence, the analysis of what is articulated in these aspects will allow us to understand the legal conduct of the captains general, consignees and emancipated people.

The Cuban colonial authorities did everything possible so that the emancipated people did not know their official legal status. The fear that these would be part of the free community of color generated concerns regarding the possible outbreak of a racial revolution similar to what happened in Haiti and the impact it would have on the enslaved sector since there has always been the idea that the of free status influenced the slaves to fight for their rights. The main interest was to maintain the balance between slaves and free.

Another important reason for continuing to falsify their condition was the authorities' interest in maintaining a enough slaves in productive activities. The captain generals had the responsibility of consigning them first, then they began to rent them and later to hire them. Hence, the emancipated workers, starting in 1835, were seen as the possible solution to make up for the shortage of labor and began to be used as a workforce in various workspaces.

Hospitals, charitable establishments and other government institutions (Government House, Political Secretariat) were favored in receiving emancipated people. However, individuals and corporations were the two sectors that benefited the most. The largest percentage of those destined for field work were in the sugar mills, but there is also news of them in coffee plantations, haciendas, pastures, meadows, ranches, work sites and other farms.2 They provided domestic services in private homes, as well as other jobs typical of the urban context such as cigar makers, water carriers, carriage drivers, bakers, stokers and shovelers on war steamers.

But above all, just like the maroons and the prisoners, they constituted cheap labor to be used in construction plans throughout the entire Island. The information compiled in the ANC shows that the Royal Development Board was the main corporation to which they granted themselves emancipated. They were destined for multiple public works such as the construction of the Roncaly Lighthouse, at Cabo de San Antonio and the fortification at Punta de Maternillos. They built roads and paths throughout the Island. They were used in such important and difficult jobs as the construction of the Railway, the Hospital for the Demented in the Ferro pasture and the aqueducts of Fernando VII first and that of Vento later.3–5 In road work, for example, they were dedicated to various jobs: stone splitters, carters, etc. Within this broad work universe, emancipated women were generally engaged in the tasks traditionally assigned to them, such as washing, ironing, sewing, and cooking. They also performed the same forced labor and lived in similar working conditions as men.

This is why what at first constituted a problem became a succulent business for all those involved in the life of the emancipated on the Island. First, the consignees began to positively value the consignments for their low cost. Although the aspect of remuneration—referring to the rent that the consignee paid to the Government by consignment—was one of the elements that was barely clarified and one of those that suffered the most variations within the consignment system, the emancipated always constituted a labor force lower prices than slaves.

Second, the consignments had to be for a certain period but the consignees had the possibility of avoiding their return at the end of said period, for which many were converted into slaves. These legalized mechanisms, only through practice, resulted in the extension of the consignment and an increasingly smaller number of emancipated people who managed to obtain their emancipation letter. The Captains General, who were responsible for this transfer, established the practice of extending the appropriations not for three but for five more years, if the interested parties expressed the prior donation and other stipulations.

The extensions were not the only business articulated around the consignment system. Thirdly, many of those emancipated were consigned to supposed people, that is, who had never existed and another number were considered dead without their employers having justified it. Likewise, rentals, transfers, subleases - other recognized forms of distribution for emancipated people - were used by the Government to get rid of maintenance charges and as an object of profit for the consignees.

Another element that shows the advantages for the consignees was the right granted to them to return them if they became unusable. Many were left disabled in one arm or leg; others were left blind. To take care of these Africans, the Emancipated Protective Board bought the Potrero Ferro to establish a health care house there, in which it was their duty to feed, clothe and cure them.

Although measures were implemented in the regulations for the emancipated to establish good treatment and prevent their reduction to slavery, the provisions were repeatedly broken. The captain generals considered it inconvenient to grant complete freedom to “savage” people, who were unaware of the means to earn a living and therefore would not know how to make use of it.

The special context of legislative and institutional renewal offered with the reorganization of the Emancipated Branch resulted in a major reform of the judicial administration system in Creole Cuban society. The emancipated were given the right to be defended by the trustees in court by Royal Decree in 1856. The trustees12 They oversaw processing these matters in the judicial processes of the slaves and therefore, they became representatives of the slaves before the law of their masters.3 On the other hand, in the processes for emancipated people, these figures were the ones who had the function of appearing before the fact, preparing, instructing and writing the file. These, together with emancipated people and consignees, had to swear fidelity to their obligations.

The Royal Decree of 1856 also stipulated that claim had to be heard in the Protective Board of Emancipates, also referred to in the files as the Bureau of Emancipates, or in the Royal Pretorial Court. According to article VIII of the Concha Ordinance, the Emancipated Protective Board would become the main body for any claim because, upon hearing the complaint presented fair, it had to notify the Superior Government. For this reason, in the legal processes he collected all the documents - consignment, rent, payment letters, security card - that the employer had to present to compare with those that he had to have in his file. By 1871, given the law of gradual manumission of slaves and complete freedom of the emancipated, its dismantling was thought appropriate; However, the number of claims, the prosecution of fraud, the formation of censuses that said law implied; for this date; influenced its permanence as an institution.

The Depósito was another of the institutions that played a fundamental role in the legal processes, since the emancipated had to enter immediately upon appearing in any court. Those residents of the city of Havana entered the Central Depot of Emancipados,13 while those who were in other regions of the country were in the maroon deposits of said regions, as demonstrated by the case files in Pinar del Rio, Matanzas, Santi Espíritus, just to mention a few examples.

After the Central Protective Board of Freedmen was established, created by the Law of July 4, 1870, the Government decided to abandon the powers it had been exercising regarding the protection of the emancipated. On July 30, 1873, those remaining in the Emancipados Central Depot were extracted, and the key to it was handed over to the owner of the property, Mr. Francisco Javier, in August 1873.14 So where did the Africans who still presented themselves for transfer of patronage, returns or claims processes that existed in the 1970s go? Documentary sources show contracts for properties to function as temporary warehouses in other areas of the city.15

It is necessary to clarify that in the analysis of the claims processes it is not possible to see whether the emancipated person who arrives at the warehouse, for this reason, can be consigned or sent to other workspaces until a solution to the claim is reached. However, Mr. José Espárrago y Cuéllar (1868, p. 34.) in the reform for the branch of emancipated people that he presents to the Captain General says: (….) the muzzles are worse cared for and educated in the warehouses, than when they are consigned (…) And what will I say if the existing emancipated people are collected in the warehouses, and they are made to work on behalf of the Government, paying them six or seven monthly pesos each, when free blacks or slaves earn twenty-five or thirty?

It is interesting to highlight the idea that Cuéllar points out about the attitude taken by the Government with those emancipated people who are collected and placed in the warehouses. All consignees of emancipated persons in claims processes stop paying the advance fees corresponding to the established semesters. In the year 1856, for example, the Government stopped receiving 10,000 pesos for this concept.16

Together with the institutional and legislative renewal, the royal orders and decrees gave birth to a new policy regarding the slave trade. Hence, in the sixties a different dynamic began: declaring the group of expeditions captured between 1824-1836 exempt from government dependence. In general, it was established to grant freedom to men and women who nominally had to be declared free at least two decades ago.

If we take into account the average useful life of work and the average age at the time of the sentence, it will be understood that these projects were not aimed at declaring as free Africans who were still in a fertile working age, but rather to those who had survived a group of incidents and many were over 40 years old and older. And even so, the provisions referring to the group of emancipated people introduced before 1835 were repeatedly breached. But if the legislation shows the decrease in that resistance to declaring the emancipated people exempt from dependence on the Government, in practice, they did not want to enforce it. the new measures and maintain the state of things: the hiring of freedmen, rent requests and transfers continued.

The colonial legislation and its legal framework for Cuba did not facilitate the development of legal actions by the emancipated to improve or change their life situation until after the fifties of the 19th century, in which a group of conditions occurred that allowed the increase in these claims. Despite the advantages that the legislation continued to grant to the consignees and colonial authorities, institutional and attitudinal changes were introduced that opened up real possibilities for the period 1856 to 1880 to give a boost to the claims processes. Particularly the stories of those emancipated women, and especially mothers who approach the courts, reveal the legal strategies used to demand freedom and the improvement of their own living conditions and that of their most loved ones: their children.

9Great Britain also signed treaties with Portugal, Holland, the United States and five Spanish American republics: Chile (1839), Argentina (1839), Uruguay (1839), Bolivia (1840) and Ecuador (1840), which provided for the creation of Mixed Commissions in Sierra Leone, Luanda, the Cape of Good Hope, Cape Verde, Rio de Janeiro, Jamaica and Suriname. See: Arnalde Barrera, Arturo. (1992). The Mixed Anglo-Spanish Court of Sierra Leone, 1819-1873. (Doctoral Thesis). Complutense University of Madrid. Spain. For a more detailed analysis of the Treaty of 1817 and the Treaty of 1835, See: Meriño, M. A and Perera, A. (2015). Bozales smuggling in Cuba: pursuing trafficking and maintaining slavery 1845-1866. Mayabeque: Montecallado Editions.

10National Archive of Cuba (ANC), Miscellaneous Files, leg 3713, num. Bz. Report on the branch of emancipated people of the Island of Cuba, formed when the delivery of command of this Island to the Hon. Mr. Don Francisco Serrano, Count of San Antonio, by the undersigned Lieutenant General, Don José Gutiérrez de la Concha, Havana, 1855.

11(…) the condition of the emancipated people of Havana is worse than ordinary slavery. See: Turnbull, David (1840). Travels in the West. Cuba with Notices of Porto Rico, and the Slave Trade. Longmans, London.p. 75.

12The trustees were public servants who acted as the protectors of the slaves and who were supposed to know how to decide in the first case on the validity of their claims.

13National Archive of Cuba, Havana (ANC), Miscellaneous Files, leg. 3708, no. Az. About the rental contract for the citadel where the Emancipados Central Depot is located, Havana, 1868.

14National Archive of Cuba, Havana (ANC), Miscellaneous Files, leg. 3723, no. Year File on suspension of the Emancipados Central Deposit, Havana, 1872.

15National Archive of Cuba, Havana (ANC), Miscellaneous Files, leg. 3657, no. Ab. Regarding the application presented by Mr. Severo Portaz, resident of Calle del Príncipe Alfonso No. 1, requesting the amount of the rent for the house that he rented as a deposit, Havana 1867.

16BNE. Manuscripts. Trades changed upon emancipated between 1850-1858. About the emancipated ordinance. A balance of the situation. p. 186.

The project that justified the slavery of Africans and their descendants has placed the slave woman, in her social role, as a laborer, midwife, nurse or nurse. Several authors have supported the thesis of the impossibility of talking about maternal feelings in slave women, since they murdered their children "because they preferred to see them dead rather than slaves (Vainfas, 1999).6,7

These positions have been overcome by interesting and documented studies such as that of Aisnara and Meriño,8,9 Richard Follet (2003) and Eugene Genovese,10 which raise the social and legal meaning of motherhood for slave women. These authors analyze several factors that could influence the frequent losses of infants, such as the exhaustion of slave mothers after working long hours, which hindered their reflexes and frustrated their maternal performance.

Among women subjected to slavery, motherhood was generally assumed as a value foreign to them. But the presence of women in these legal processes shows how the emancipated women played a fundamental role in the preservation of their family. The fact that the mother is responsible for transmitting her condition to the legal status of the children means that in the processes to prove an emancipated condition, her motherhood is placed at the center of the dispute. According to the legal regulations, the children that the emancipated women had at the time of their arrest, as well as those that they had after the declaration of emancipation, would be consigned to their mothers - and remain under their care - until the age of fifteen, the latter without be subject to the status of settlers.17

This is why, although the various strategies used by the slave sector with the aim of achieving their freedom are known. Many rebelled, others resisted slave rule by becoming a “bad slave” to lower their prices in the market or change masters. Some hoped to obtain the lord's approval or accumulate a wealth that could be insufficient when its price was stipulated.8 Saying “be emancipated” in court was a strategy to try to defend your right to be free.18 Such was the case of Micaela Vallar, a slave sold for the price of 500 pesos by Mr. José Vila to Mrs. Salome García.

The records of slaves who decide to prove an emancipated condition show that, even though the number of emancipated people was a minority compared to the slave population, the opportunity to form chains among them existed. Slaves and emancipated people lived common experiences: they received the same punishments, they served the same masters, they were employed in the same tasks, they were dressed and fed in the same way. Manuel Barcia (2006, p. 167) points out: "They speak, they make their comments and more than once it is possible to hear them use words with double meanings and certain comments." Thus they managed to accuse their consignees/owners and use the law for their own benefit in protests based on this knowledge.

In the court of Port-au-Prince in 1867, the request made by Antonio Benítez Pardo, a bricklayer by profession, was not valid. Antonio's two natural children - José de la Rosa, 4 years old, and María Bartola, 2 years old - remain under the care of his mother, the emancipated Catalina, assigned to the Infantry Captain Dn. Augusto Ullon despite there being evidence that he oversaw supplying him with what he needed in food and clothing.19

On the other hand, considering what is established in the legislation, the emancipated Rosa or Juana, member number 288, from the capture of Santi Espíritus and Trinidad asks that her children: Pedro and Ceferino, who are working on the Dam, be in her care. up to the age that the same article prevents. Such a situation was resolved by the resolution in article 6 of Chapter 1 of the Emancipated Orders, in 1867, recognizing their maternal rights.20

For her part, Trinidad, daughter of the emancipated Josefa de Jesús affiliated with number 238 of the Gerges expedition, at the age of 26 went to the authorities to demand her freedom. In her statement, Trinidad explains that at the age of 6, when her mother died, she was placed under the consignment of Mr. José Martín as a domestic employee, and that, having now reached the age of majority, she placed herself at the disposal of the Government to obtain her letter of freedom. He also alleges 3 fundamental reasons for presenting his petition: “he considers that he requires the necessary circumstances to enter into the enjoyment of the rights that free people have, he considers that if his mother had not died, she would have been declared exempt from the same as her. dependence on the Government and finally that he would achieve the necessary conditions to care for the upbringing of his 7-year-old son Salomé.21

Finally, we present the request presented by the emancipated Margarita Fusebo to be provided with a free identity card. Her goal was for her two children, Manuel and Candelaria, to also be declared free.22 Margarita's story reveals how legal mechanisms also constituted a strategy to protect the family she created from slavery or poverty.

The documents presented so far define the emancipated mother as protagonists of the destinies of their children, through the tough battles developed in legal claims, by presenting as a legal argument that they can take care of the upbringing of their children. Even though motherhood was another of the forms of control developed by the masters, another highly relevant factor that shows that the mothers did not docilely accept the annulment of their maternal ties due to the breaking of slave legislation was their act of denouncing the slaves. abuses committed with their children.

Many of these children were turned into slaves. The consignees did not declare them as born nor did they register them in the parish registries and on several occasions they chose to keep children of deceased emancipated mothers without informing the Government. Such was the case of José, son of the emancipated Manuela affiliated with number 689 of the capture of the “Santi Espíritus and Trinidad”, who at the age of 20 was still rehired at the “María” mill, owned by Dn. Gabriel Pérez and Ricart.23 José's own statement also states that the administrator of said mill put him in shackles. In this way he was restricted from a right that belonged to him: his freedom.

Another of the abuses committed with the children of the emancipated women was the lack of concern on the part of the consignees in their care. The number of files that can be found in the ANC on the deaths of emancipated children seems to indicate that the consignees were neither affected nor concerned by such a situation. Hence, as Miguel Estorch - Member of the Emancipated Protective Board, created by Captain General José Gutiérrez de la Concha in 1851 - would say that most of the females were sterile or many abuses had been committed.2

It is true that the limited knowledge that was had at the time of the diseases that affected the child population and the poor conditions that existed in the destinations to which they were consigned and in the warehouses also influenced the death of their children. In the warehouses for public works, for example, according to the description of the Director of Public Works Gabriel Cárdenas himself, in his first inspection of the Cimarrones Storage House, he stated that it was a necessity to look for a room that would serve as a relief for the blacks, who they all slept in a narrow room.

The living room had a newly made plank floor and could not be cleaned. The filth of the blacks, which is inevitable, seeped through the cracks where the water did not enter to clean but to stay and conserve humidity, always giving off a bad smell and dirt.24

A significant example of women who mourned the loss of their children were those sent for public works (Table 2).

|

Data of the emancipated other |

Toddler Data |

||||

|

Name |

No |

Expedition |

Name |

Age |

Year of death/ Death cause |

|

Assumption |

3592 |

Aguica |

Sebastiana |

11 months |

1868 /Enteritis |

|

Aguica |

Saturnine |

6 months |

1870/Whole=chronic colitis |

||

|

Monserrate |

3656 |

Aguica |

Matilda |

1864 |

|

|

Florinda |

3352 |

Aguica |

Victory |

4 years |

1870/Whole=chronic colitis |

|

Telesfora |

3995 |

Aguica |

Julia |

2 years |

1869/Mesenteric tibis |

|

Vincent |

3550 |

Aguica |

Venancia |

1867/Acute enteritis |

|

|

Timothy |

3587 |

Aguica |

Manuela |

1869/ was born with an ulcer on his head, and the coronal and parietal bones were almost destroyed. |

|

|

Carmen |

3023 |

Canoe |

Paula |

1867/ Chronic diarrhea |

|

|

Brigida conga |

305 |

Pools |

Bernardino or Federico |

2 years |

1867/ Dysentery |

Table 2 Emancipated women assigned to public works

Fountain: Database created by the author of death records of emancipated children from the National Archive of Cuba of the Miscellaneous Records Fund.

The experiences lived show some of the different forms of control, abuse, and business on African women, but above all they were deprived, to a certain extent, of the protection in the legislation of their personal relationships as mothers. The law recognizes the right of employers over the children of their enslaved women. They were victims, together with their children, of abuse and punishment, but at the same time they knew how to demonstrate that they were competent as mothers and the fairness of their claims in legal processes.

17Historical Archive of Madrid, Spain, (AHM), Ultramar, 04666, Exp. 002, N.028.

Historical Archive of Madrid, Spain, (AHM), Ultramar, 04666, Exp. 001, N.001. About the New Emancipated Regulations.

18National Archive of Cuba, Havana (ANC), Miscellany of Files, leg.3660, no. Ac. On the marital status of Micaela Vallar, Havana, 1868

19National Archive of Cuba, Havana (ANC), Miscellany of Files, leg. 3701, no. Bd. On a request made by the brown man Antonio Benítez so that the 2 children that he has with the emancipated Catalina be given to him. Port-au-Prince, 1867.

20National Archive of Cuba, Havana (ANC), Miscellaneous Files, leg. 3700 no. W. Petition of the emancipated Rosa or Juana no. 288 Santi Spirits and Trinity so that hers may be placed in her care. Havana, 1867.

21National Archive of Cuba, Havana (ANC), Miscellaneous Files, leg. 3700, no. Ba. Regarding the communication that Mr. José Martin has addressed to the Lieutenant Governor of San Juna of the remedies, making his disposal to Trinidad, daughter of the emancipated Josefa. Havana, 1867.

22National Archive of Cuba, Havana (ANC), Miscellany of Files, leg. 3657, no. Y. Mr. Ramón Abreu goes to that deposit to choose an emancipated one granted by HE in exchange for Baldomera No 189 Isla de Pinos that he has returned. Havana, 1870.

23National Archive of Cuba, Havana (ANC), Miscellaneous Files, leg. 3651, no. O. File filed by Eleuterio and José María Trinidad, from the emancipated class, complaining that some recontracts have been extended without their consent. Pinar del Río, 1878.

24National Archive of Cuba, Havana (ANC), Royal Consulate and Development Board, leg. 5, no. 263. Report of the Director of Public Works on the Depot House and on roads. Havana, 1823.

The story of the emancipated Luisa Conga - in her country Yumba -, affiliated with the number 5128, of the capture of the 3rd Neptune, is one of the documented cases in which she uses institutional means to complain and thus negotiate a better situation not only for her but also for her son. In 1867, when she had been in the service of Don José Castroman for 3 years, she appeared at the Emancipated Bureau demanding that her consignment in this house be terminated and that her entry into the Central Deposit be arranged. According to Luisa's own statements, "... Don Castroman's wife mistreated her for having had a 1-month-old child with said employer..." This child had been the result of the sexual abuse that she had suffered. Luisa managed to achieve a change in her situation by obtaining a favorable solution to her request.25

There are many stories that tell of such unfortunate experiences that in turn refer to the intimate relationships formed between the enslaved and the family life of their consignees. The legal and moral implications that united white families and black families were used by emancipated mothers as an argument or reason in defending their requests. The emancipated Luciana Conga, affiliated with number 144 of the capture of the "Second Neptune" appeared at the Emancipated Bureau expressing that her employer Mrs. Salvadora Rubio "...did not give her clothes, shoes, good food or the three pesos a month to which I was entitled.” She alleges that, “…in addition to ironing and washing, she was forced to make the beds and sometimes mop the floors on Sundays and she only lets her go out once every 3 Sundays.” She also explained that “… they put him in shackles for three days when he asked for soap to wash her clothes, telling him that she spent a lot because she was pregnant.” In the end it was decided to admit Luciana and her two children - Agueda, 3 years old, and Catalino Pilar, six months old -, to correct their faults, in the Paula Hospital to serve as the laundromat of that asylum for two months.26

These stories also show disagreements with certain behaviors of the consignees and also reveal certain details about the living conditions in the different destinations to which they were consigned. The exposed documents also reveal some of the reasons for filing a complaint against its consignee. The extension of contracts already fulfilled non-payment of monthly payments, the collection of letters of freedom, threats of being sent to the sugar mill, mistreatment, punishments and beatings, the increase in working hours and tasks at work are some of these causes. But, the intimidation with the retention by the employer of the infants was another reason for emancipated women who had children. Such was the case of the emancipated Julia, affiliated with number 722 of the capture of Cayo Sal, who testifies that her employer Doña Beatriz González has told her to take away her daughter Benita, so that she could work more.27

Many were not able to change the course of their lives and in exchange they received punishment by being sent to hospitals, public works or charitable institutions, to undergo a period of correction. In the first 30 years of the group's existence, there is a small sample of emancipated women who were sent to the Development Board to work in the Husillo pipes, in road work and on the Camino of Hierro as corrections. Although it is true that on this date there are no claims processes, it demonstrates the extension of said practice until the definitive disappearance of the group of emancipated people.

The emancipated women were subjected to sexual abuse. They were not only abused by those who were supposed to instruct and moralize them but also while in the warehouses.28 In 1866, a case appears signed by Don Manuel Rodríguez, caretaker of the aforementioned warehouse, complaining about the poor treatment to which the emancipated people were subject. As a result of the investigations into the clarification of the reported abuses, it was found that the foreman gave cruel treatment to the blacks of both sexes, punishing them terribly when they complained that they were not given enough to eat, hitting them with the handle of the whip, and for this reason he punished a black woman so excessively that there was no point on her body where blood did not come out. And, also using threats and punishments, he abused women to provide himself with illicit pleasures.29

On more than one occasion, the consignors believed they had the right to mistreat and punish them. Some authors try to justify such behaviors. According to the opinion of Mr. José Espárrago Cuéllar (1868, p.25) when stating that “as the consignee pays his money to the Government for the emancipated people that he delivers to him, he is excusable for any excess he commits to make his money produce more money.” On the other hand, Article # 7 of the consignment or contract documents allowed the consignees to impose, if necessary, the corrections of stocks, shackles or arrest for 1 year and, on the other hand, the loss of salary during the same time. They would be disciplined for lack of subordination to consignees or employers, resistance to work or lack of punctuality in the performance of their tasks, escape, drunkenness and violations of their employer's disciplinary laws.30

On the other hand, many consignees were willing to negotiate their interests. Hence, despite being in a judicial process that could last months without a ruling for any of the parties involved, they did not renounce the contributions of the emancipated plaintiffs. Of the total cases examined, 32.6% had a favorable result for the consignees. Although the slave system, starting in the 1950s, allowed the emancipated to defend their rights; This indicator shows that the colonial authorities always maintained their criterion that the emancipated represented a danger to the tranquility and maintenance of slavery on the Island.

However, the files that appear in the National Archive of Cuba on transfers of patronage and returns point in another direction to the strategy of other consignees. By the sixties there was an increase in these new practices. There are numerous requests from employers asking the Government to exchange women for men or for other women, who, above all, do not have small children. Don Ramón, who had the emancipated Rosa for rent, affiliated with number 288 of the capture of the “Santi Spíritus”, requests her return and that she instead be, granted Pedro, one of her children.31 Don Esteban appears at the Superior Civil Government of the Island to transfer the patronage of Clara affiliated with number 148 of the capture of the “Maniabón”. According to his statement, it was not possible for him to continue paying the assigned fee, so he wanted to return it with his 5-month-old son, Emilio Serafín.32

A reading of these files shows that the largest number of referrals was precisely among emancipated women, especially those who had small children. As explained above, the consignees did not wish to have emancipated women who had children under their patronage, since according to the legal regulations, the children that the emancipated women had at the time of their arrest, as well as those after the declaration of emancipation, would be consigned with their mothers. This situation would bring two inconveniences for consignees. First, in the slave order the son inherited the condition or legal status of the mother. Second, they had to be cared for and assisted until the age of fifteen.

The stories that accompany this article about the study of legal actions used by emancipated women in Cuba in the period between 1856 and 1880 may not be the only ones. Many others wait to be found in the documentary sources housed in the National Archive of Cuba.

25National Archive of Cuba, Havana (ANC), Miscellaneous Files, leg. 3663, no. An. Complaint against her employer Mrs. Salvadora Rubio by the emancipated Luciana No. 144 2nd Neptuno of the Conga nation. Havana, 1867.

26National Archive of Cuba, Havana (ANC) Miscellaneous Files, leg. 3656, no. Cñ. About the complaint that the emancipated Julia makes against her employer. Havana, 1867.

27The stay in the warehouse was not permanent, until they were consigned, since it was nothing more than the place where they were fed, cured, and distributed for work. All those who were part of what Professor María del Carmen Barcia calls “Black Force” lived in the warehouse (Barcia, 2016). Those consigned to individuals or to institutions such as Hospitals or Corporations lived in other spaces. In the case of those who worked in the Streets Branch, they could be kept in the warehouse, so that the Administrator could take them at 8 in the morning and return them in the afternoon, if they met the transportation for their food and formation of the numerical status of emancipated people who went to work daily.

28National Archive of Cuba, Havana (ANC), Miscellaneous Files, leg. 3714, no. Bx. Regarding the summary carried out in the investigation of abuses of the Emancipados Central Depository. Havana, March, 1866.

29National Archive of Cuba, Havana (ANC), Miscellaneous Files, leg. 3720, no. J. Marianao Railways. Havana, June, 1868.

30National Archive of Cuba, Havana (ANC), Miscellaneous Books 1701, Emancipated Bureau. Registration of the files that are instructed by the Head of the Bureau. Havana, March 1, 1867.

31National Archive of Cuba, Havana (ANC, Miscellaneous Files, leg. 3653, no. Ah. On request presented by Dn. Esteban Minie to the Civil Government of Cuba transferring the patronage of the black Clara No. 148 of Maniabón. Havana, 1867.

32National Archive of Cuba, Havana (ANC), Miscellany of Files, leg. 3703, no. Ae. Instance presented by the emancipated Luisa No. 5128, 3rd Neptune in complaint against the wife of Dn. José Castroman, Havana, 1867.

Files to prove emancipated status, requests for letters of freedom and instances of complaints against consignees constitute some of the claims processes promoted by emancipated women to defend their dual status as women and mothers. These strategies elevate the meaning of motherhood in slave societies, evidencing how the slave woman played a fundamental role in the preservation of her family, especially her children; changed the meaning of freedom when, far from not wanting to see their children subjugated, they fought to raise them and sought to improve the living conditions of their children in response to the denunciation of the conversion of their children into slaves, the concealment of their births and poor care. to which they were subjected.

The legislation had not denied her maternal capacity. However, the development of different legal actions that give new value to the vision of motherhood was possible during the period from 1856 to 1880, in which important conditions occurred. First, the interest of the colonial authorities in establishing a group of decrees, provisions to grant letters of freedom to those emancipated from the expeditions captured between 1824 to 1836. Together with the granting in 1856 of the right to be defended by the trustees in court because of the great reform of the judicial administration system of the 1950s in Cuban society. This Royal Decree not only shed light on the legislation but also caused an institutional renewal by creating new institutions whose function would be to process the claims of emancipated people. Among these are the Emancipated Protective Board, also referred to in the files as the Emancipated Bureau, and the Emancipated Central Depository.

The testimonies of emancipated mothers collected in this article give the opportunity to learn about the situations in different environments in which they were consigned, the reasons why they approach the courts, the possible sentences among other issues. At the same time, this article makes us think, from a gender perspective, about the complexities of the Cuban slave society.11–21

None.

The author declares there is no conflict of interest.

©2024 Martí. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.