MOJ

eISSN: 2379-6294

Research Article Volume 4 Issue 1

Department of Pharmacology, University of Costa Rica, Costa Rica

Correspondence: María del Mar Castillo Guerrero, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Costa Rica, San Pedro, Montes de Oca, San José, Costa Rica, Tel 5062 5118 317, Fax 5062 5118 350

Received: February 08, 2018 | Published: February 19, 2018

Citation: Guerrero MMC, Mora FA. Poisonings and deaths caused by benzodiazepine drugs in costa rica, from 2007 to 2014. MOJ Toxicol. 2018;4(1):34–37. DOI: 10.15406/mojt.2018.04.00087

Background information: Medications are the main cause of poisoning in Costa Rica, and benzodiazepines are reported in many of the poisonings that occurred.

Objective: Analyze the poisonings and deaths caused by benzodiazepines in Costa Rica.

Method: A retrospective study was conducted. It included all the cases of poisonings and deaths by benzodiazepine poisonings in Costa Rica from 2007 to 2014. A logistic regression analysis was conducted to determine the probability of a person of dying by benzodiazepine poisoning. A descriptive analysis was performed with the information of the total population of people intoxicated by benzodiazepines.

Results: People intoxicated by benzodiazepines have higher possibilities of dying, than those who were not poisoned by benzodiazepines. Most cases of poisoning with benzodiazepines correspond to women in the 30 to 44 age range. Attempting suicide is the main cause of poisoning. The combination of benzodiazepines with other substances such as antidepressants, anticonvulsants and alcohol prevails in cases of deaths by poisoning with benzodiazepines.

Discussion and Conclusion: The main cause of poisoning is suicide attempt, so the potential high suicide risk that exists with the use of these drugs should be monitored. Most of reported cases of poisoning are in women, which are associated with higher rates of consumption of these drugs. Most deaths are associated with combinations of benzodiazepine and other drugs or with substances such as alcohol.

Keywords: benzodiazepines, poisoning, death, suicide, sedative, hypnotic, anxiolytic, anticonvulsant effects

Benzodiazepines are drugs that act on the central nervous system. Among others, these drugs have sedative, hypnotic, anxiolytic, anticonvulsant effects. Benzodiazepines bind to BZ receptor site of, which is a chloride channel in neuronal membranes of the central nervous system. These drugs do not directly activate receptors, but modulate GABA effects by an allosteric action.1 These drugs cause sedation effect at low doses and can induce sleep if the dose is sufficient. However, high doses produce central nervous system depression. They can even be used to generate anesthesia and respiratory depression.2 Benzodiazepines can be classified according to the duration of their action on the body. There are short-acting, intermediate-acting and long-acting benzodiazepines.3 Short-acting benzodiazepines are metabolized rapidly and many of their metabolites are inactive. For example, triazolam or midazolam are short-acting benzodiazepines used mainly to treat insomnia, reduce anxiety and alcohol withdrawal symptoms. Intermediate-acting benzodiazepines such as alprazolam and lorazepam are used for night sedation, muscle relaxation and anxiety symptoms. Long-acting benzodiazepines, such as diazepam or clonazepam, are biotransformed in the liver and many have active metabolites, these are used mainly for sedation and to reduce anxiety. The main use of benzodiazepines is due to their anxiolytic and hypnotic effect. However, treatment guidelines recommend a more restricted use and the selection of new drugs to treat anxiety and insomnia.4 Guidelines also suggest proper compliance with therapies for the treatment of depressive disorders, personality disorders and panic.5

In many cases physicians ignore the existing guidelines for prescribing benzodiazepines. In some countries ignoring the guidelines has become the norm, so two options have been proposed to address the problem: apply stricter guidelines or adapt the guidelines to daily practices. Many elderly patients suffer from chronic insomnia, which makes difficult to restrict the use of benzodiazepines to a short time. This strengthens the idea of adapting the guidelines to the real life. The use of placebos and stricter monitoring of polypharmacy patients are some alternative ideas offered.6

The widespread use and abuse of benzodiazepines can be explained by their ability to cause tolerance and dependence in the patients.7 Elderly people are a population at particular risk, because they are prone to become chronic users.8

In Costa Rica, drugs are the main poisoning agent.9 Although benzodiazepines are not associated with high toxicity even after a high dose,10,11 when combined with other central nervous system depressants, the interaction can induce serious consequences for people and in the most severe cases even cause death. Due to the wide use of benzodiazepines and possible abuse, the aim of the research was to analyze the cases of poisonings and deaths caused by poisoning with benzodiazepines in Costa Rica.

A retrospective study was conducted from January 1 2007 to December 31 2014, including all the cases of poisoning and deaths by benzodiazepine poisoning produced in Costa Rica. The information of the cases included were the ones induced by clonazepam, diazepam, lorazepam, alprazolam, bromazepam, ethyl loflazepate, midazolam, clobazam, clorazepam, chlordiazepoxide, flunitrazepam, mexazolam, nitrazepam, prazepam, temazepam and triazolam.

The poisoning cases information was taken from the National Poison Control Center (NPCC). The poisoning cases included in the research had at least one benzodiazepine drug. In total, the population of intoxicated people by benzodiazepines, from 2007 to 2014 was 5243 cases. The information of deaths caused by poisoning was obtained from the Division of Forensic Pathology, Department of Forensic Medicine of the Judicial Investigation Department (OIJ in Spanish) of Costa Rica. The deaths selected had the presence of at least one benzodiazepine as the cause of death, whether primary, secondary, tertiary or as a joint cause. In total from 2007 to 2014, 53 people were killed by poisoning with benzodiazepines.

Statistic analysis

A descriptive analysis of the population intoxicated with benzodiazepines was conducted according to the variables: age, sex and cause of poisoning. The age ranges were: 14 years or less, 15 to 29, 30 to 44 years, 45 to 59 years and 60 years or more. The cause of poisoning was classified, according to the categorization used in the National Poison Control Center in: suicide attempt, accidental, self-medication, adverse drug reaction, medication errors, addiction and others. Additionally, the probability of a person dying due to poisoning with benzodiazepines was determined using a logistic regression analysis. R program (The R Project for Statistical Computing) was the package used for statistical analysis.

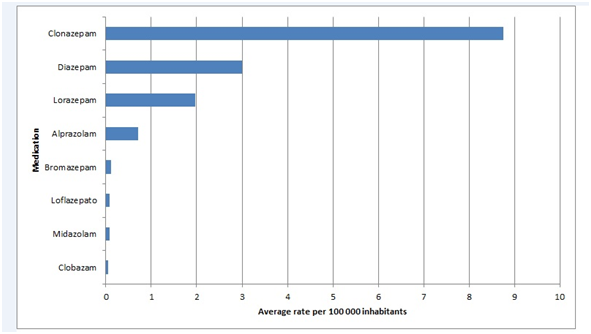

In Costa Rica, from 2007 to 2014, between 550 and 750 cases of poisoning with benzodiazepines were reported. Figure 1 shows the number of cases reported from 2007 to 2014. With respect to the number of cases of deaths reported from 2007 to 2014, the variations in different years are reported, with a maximum of ten deaths in 2012 and one case in 2008. Figure 2 shows the rates of poisoning per 100,000 inhabitants of the drugs studied. The average rate per 100,000 inhabitants during the study period indicates that clonazepam is the drug primarily responsible for poisoning with benzodiazepines in the country.

On average, there are nine clonazepam poisonings each year per 100,000 inhabitants. Clonazepam is followed by diazepam, which is responsible for three cases of poisoning each year per 100,000 inhabitants. Clorazepam, chlordiazepoxide, flunitrazepam, mexazolam, nitrazepam, prazepam, temazepam and triazolam caused less than ten poisoning cases during the study period, which is why those were not included in the graph shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2 Average rate of drug poisoning with each benzodiazepine per 100,000 inhabitants in Costa Rica from 2007 to 2014.

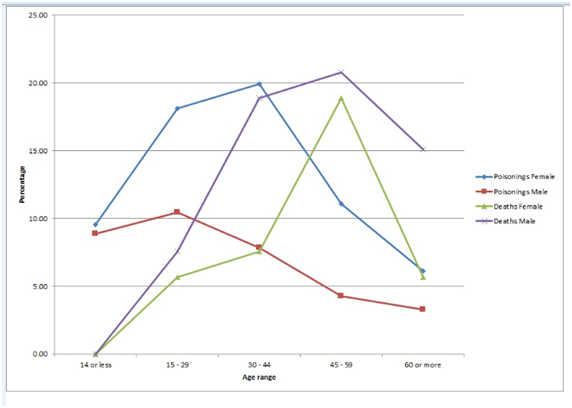

Figure 3 Age range and sex in cases of poisoning and deaths caused by poisoning with benzodiazepine in Costa Rica from 2007 to 2014.

Most cases of poisoning with benzodiazepines occur in women between the ages of 30 and 44 years. In men, the greatest number of poisonings occurred between the ages of 15 and 29 years. Regarding mortality, there was a higher incidence of death in men between the ages of 45 and 59 years. Figure 3 shows the percentage of cases that occurred during the study, according to age and sex. Attempted suicide is the primary cause of poisoning, followed by accidental causes. During 2007 to 2014 occurred 2885 cases of attempted suicide with benzodiazepine poisonings and 579 of the poisonings with benzodiazepines were because of accidental causes. Other causes were: self-medication (386 cases), side effect to medication (323 cases), medication errors (276 cases) and addiction (106 cases).

A logistic regression analysis was performed based on the data for poisonings and deaths with benzodiazepine drugs that occurred in Costa Rica between 2007 and 2014. The probability of death caused by poisoning was determined for the following variables: age, sex, drug, race, nationality, occupation, marital status, place of poisoning, type of poisoning and manner of death. People intoxicated with benzodiazepines are 1.47 times more likely to die (p˂0.1) than those who are not poisoned by benzodiazepines.

Table 1 shows the number of cases of poisonings and deaths caused by benzodiazepines as the single agent responsible and in combination with another psychoactive substance or depressant. Regarding poisonings, 2714 cases (58%) correspond to poisonings by benzodiazepines only. However, by analyzing the deaths, it appears that only in three cases (6%) was a benzodiazepine reported to be only drug responsible. Combining it with other substances such as antidepressants, anticonvulsants and alcohol is associated with a higher percentage of death cases, due to a higher risk for interactions that may occur. In the case of combining benzodiazepines with other substances, opioids, antipsychotics, analgesics, antihistamines, and other drugs are included (Table 1).

Combination |

Poisonings |

Deaths |

||

No. cases |

Percentage |

No. cases |

Percentage |

|

Benzodiazepines |

2714 |

57.99 |

3 |

5.66 |

Benzodiazepines + anticonvulsant |

355 |

7.59 |

10 |

18.87 |

Benzodiazepines + antidepressants |

715 |

15.28 |

16 |

30.19 |

Benzodiazepines + alcohol |

376 |

8.03 |

14 |

26.42 |

Benzodiazepines + others |

815 |

17.41 |

15 |

28.30 |

Table 1 Number of cases reported of drug poisoning and deaths caused by drug combinations of benzodiazepines with other substances that occurred in Costa Rica from 2007 to 2014

Note: Any other drug that is not classified as an anticonvulsant, antidepressant or benzodiazepine is included as others.

Poisonings by benzodiazepines are common in Costa Rica and maintained a similar behavior from 2007 to 2014. Annually, there are no more than ten death cases. This low death rate is explained by the low acute toxicity of benzodiazepines.1 However, at the time of peak concentration in plasma, hypnotic doses of benzodiazepines can be expected to cause varying degrees of lightheadedness, lassitude, increased reaction time, motor incoordination, impairment of mental and motor functions, confusion, and anterograde amnesia. Cognition appears to be affected less than motor performance. All these effects can greatly impair driving and other psychomotor skills, especially if combined with ethanol. When the drug is given at the intended time of sleep, the persistence of these effects during the waking hours is adverse.1

Chronic benzodiazepine use poses a risk for development of dependence and abuse.12 Benzodiazepine dependent patients are at increased risk of using benzodiazepines in high doses for prolonged periods. They also experience increased symptoms of anxiety, neuroticism and introversion. Addicted patients are characterized by a greater number of adverse events at earlier ages. For example, they experience domestic violence, spousal addiction, or job loss.13 Prolonged use of benzodiazepines is associated primarily with a hypnotic use compared with anxiolytic drugs, used primarily for sleep disorders.5

Clonazepam is the main drug reported in cases of poisoning with benzodiazepines, followed by diazepam. According to the guidelines for the prescription of clonazepam, it is indicated primarily for the treatment of some types of seizures and panic disorders (panic), with or without agoraphobia.14 However, the large number of poisonings reported with this drug provides a warning about the possible use that is currently taking place in the country. Flunitrazepam is a drug that is not reported as cause of poisonings, unlike in other countries, where it is used for crime as a "date-rape drug".15 Women have higher rates of consumption of benzodiazepines than men.5,16 This explains a higher incidence of cases of poisoning in women. In a study in Mexico, it was concluded that women have a greater tendency to use benzodiazepines; however, the dependence is greater in men.17

Patients’ age is another important feature related to the use of benzodiazepines. Most cases of poisoning were reported between the ages of 30 and 44 years, while deaths occurred mainly in people between the ages of 45 and 59 years. This is true, despite the fact that the increased use of benzodiazepines has been associated with people over the age of 60. It has been observed that an increase in the prevalence and incidence of the consumption of these drugs occurs as age increases.5,16 The highest incidence of insomnia in elderly patients is associated with an increased use of hypnotics, such as benzodiazepines.18

Attempted suicide is the main cause of poisoning with benzodiazepines, which could be due to disinhibition and paradoxical reactions that can occur with benzodiazepines. This is consistent with research data that analyzed the role of benzodiazepines in suicide attempts. A study in Sweden concluded that hypnotic benzodiazepines were present in most cases of suicides by poisoning with medication in people over 65. In another study in Canada there is a significant association between suicide attempts and the use of benzodiazepine.19 Benzodiazepines, especially those classified as hypnotics, are common in cases of suicide by poisoning with medication, so you should be aware of the high potential risk of suicide that a patient may have with the use of these drugs, mainly high-risk patients such as the elderly.20,21

The widespread use of benzodiazepines for anxiety, depressive, personality and sleep disorders promotes the use of these drugs in combination with other drugs such as antidepressants and anticonvulsants. Combining them with other substances induces significant clinical interactions that may be caused by induction or inhibition of hepatic enzymes or additive effects with substances such as alcohol and opioids, because of central nervous system depression.22

The combined use of alcohol and benzodiazepines can trigger pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic interactions, which may have important clinical implications, such as impaired motor and neurological functions, with an increased risk of sedation.23 The interaction occurs because alcohol affects the GABA chloride channel, similar to the pharmacological action of benzodiazepines. Therefore, a summation of effects occurs. Alcohol also has anxiolytic effects, causing many people with anxiety problems and probably medicated with benzodiazepines to take advantage of this effect.24

There have been cases reported where respiratory depression continues even four days after ingestion of high doses of benzodiazepines (diazepam, nitrazepam and medazepam) and alcohol.25 There are also reports of abuse of flunitrazepam in combination with alcohol.26 The widespread use of benzodiazepines for anxiety disorders and abundant alcohol use by society make it necessary to be especially careful about the interaction that can occur between these substances.24 It is important for doctors to consult their patients about their drinking habits when they prescribe a benzodiazepine so that they can inform the patient about the interaction between both substances, and prevent potential risks.23

The main limitation of this study is the possibility of underreporting of cases of poisoning because the system does not guarantee 100% reporting of cases occurring in the country. Suicide attempt with benzodiazepines is the main cause of poisonings in Costa Rica. Clonazepam is the primary drug responsible for poisoning with benzodiazepines in the country. Most reported cases of poisoning are in women between the ages of 30 and 44 years. Most cases of poisoning with benzodiazepines include these drugs as the sole agent responsible for the poisoning. However, for deaths, most cases are associated with associations of benzodiazepines with other drugs or with substances such as alcohol.

This work was funded by the University of Costa Rica.

None

The author declares no conflict of interest.

©2018 Guerrero, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.