MOJ

eISSN: 2374-6939

Research Article Volume 10 Issue 2

Pediatric Department of Federal State Autonomous Educational Institution of Higher Education, I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, Russia

Correspondence: Osminina MK, Pediatric Department, IM Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, Moscow, Russia

Received: February 15, 2018 | Published: March 14, 2018

Citation: Osminina MK, Geppe NA, Shpitonkova OV. Articular involvement in juvenile localized scleroderma. MOJ Orthop Rheumatol. 2018;10(2):104–108. DOI: 10.15406/mojor.2018.10.00396

The articular involvement (ArIn) of juvenile localized scleroderma was studied retrospectively in 190 patients with juvenile localized scleroderma patients. Of these ArIn was detected in 125 patients (65,7%), among them 99% were in cases of linear and unilateral form of JLS. It was presented by joint pain in 25% of patients, limitation of joint movement in 62% of affected patients, mostly due to periarticular induration or tissue fibrosis, joint effusions – in 1% of ArIn. 25 % of affected children complained of joint pain. Limitation of joint movements was mostly (in 70%) due to the induration of soft tissue and skin around the joint and was reversible under therapy. Joint effusions were observed in 1% of ArIn. Ultrasound investigation imaging showed slight “subclinical” -synovitis and tenosynovitis in 80% of ArIn parients. Joint space narrowing by X-ray was detected in 12, articular erosions - in 2 children. In 1 girl with unilateral scleroderma MRI with contrasting detected avascular osteonecrosis of tibia. The levels of detected autoantibodies and markers of fibrosis were significantly higher in the patients with ArIn. All the patients with ArIn received immunodepressant therapy – glucocorticosteroids (GC) orally 1mg\kilo for 6-8 weeks, then tapered and withdrawn through the 3-6 months, and methotrexate (MTX) parenterally 12mg\sq.m. for at least 2 years. In 76% of cases of ArIn this treatment increased range of joint movements or stopped flexion contractures. Therapeutic efficacy was worse in prolonged JLS with ArIn.

Keywords: juvenile localized scleroderma, articular involvement, antibodies profile, X-ray, ultrasound changes, therapy

JLS, juvenile localized scleroderma; JSS, Juvenile systemic sclerosis; ArIn, Articular involvement; RF, rheumatoid factor; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; ANF, antinuclear factor; Cab, autoantibodies to collagen, CG, cryoglobulins;FN, serum fibronectine; HA, hyaluronic acid; GC, glucocorticosteroids, MTX, methotrexate

Juvenile scleroderma is a rare disease of childhood. It includes two main clinical entities, juvenile systemic sclerosis (JSS) and juvenile localized scleroderma (JLS). Both have a common pathophysiology, with an initial inflammatory phase of the disease associated with endothelial disfunction, and a later fibrotic phase with skin thickening. In JSS many organs and systems may be affected - vascular (Vessels) (Raynaud phenomenon), cutaneous (Skin), gastrointestinal tract, pulmonary, cardiac and musculoskeletal system, while in JLS the process of fibrosis involves manly the skin and subcutaneous tissues. Articular involvement (ArIn) is the most frequent finding in JLS, patients who developed arthritis often have a positive rheumatoid factor (RF), and sometimes elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and circulating antibodies.1

The pathogenesis of scleroderma and ArIn is compex and incompletely understood. Vascular injury, autoimmune dysfunction and connective tissue remodeling with excessive collagen production are the main pathways of the disease. Mechanism of fibrosis and the role of disease –specific autoantibodies have been extensively investigated. Antinuclear antibodies, RF, anti-double-stranded DNA antibodies and anti-histone antibodies were detected not only in the systemic,2 but also in the localized forms of scleroderma.3 Thus, according to some authors, the antinuclear factor is detected in 46-80%, antidouble- stranded DNA antibodies – in 50%, antihistone antibodies – in 47%, rheumatoid factor – in 26% of adult patients with limited scleroderma.4 There are some data stating that antinuclear factor directly correlates with joint lesions.5 Patients with rheumatic conditions often have mixed cryoglobulins, composed of class M and rheumatoid factor immunoglobulins, class G polyclonal immunoglobulins and fibronectin. The level of cryoglobulins also correlates with clinical and laboratory activity of scleroderma.

The extracellular matrix of skin, tendon and bonetissue is composed mainly of type I collagen, and of type III collagen to a lesser extent. Type II collagen is mostly located in the articular cartilage, collagen IV – in basal cell membranes. Some researchers detect type I and IV collagen molecule autoantibodies in systemic scleroderma.2 As the result of monocyte overproduction, an intensive secretion of monokines, such as fibronectin and interleukin-1 are stimulated. Fibronectin has a high affinity to the native and denatured collagen. Some data suggests that in scleroderma level of fibronectin and hyaluronic acid are increased, and could be used as biomarkers of fibrosis.6,7

The articular manifestations present both in JSS and JLS, as far as in children the incidence of JLS is fourfold higher than JSS, the articular involvement (ArIn) in JLS represents a challenge to growth disturbances. ArIn lead to severe joint contractions, orthopedic deficits and motor disabilities. Arthritis occurs in 27.5% of patients in pediatric JSS cohort and in 17% of JLS patients, in comparison to 18% in adult systemic sclerosis cohort.8

.Moreover, scleroderma affects children in the period of their intensive growth, so ArIn could cause extremity length differences, functional skeletal impairment, growth retardation of extremities (Figure 1) (Figure 2). Children with JLS and ArIn tend to have asymmetric joint involvement with no erosions, an accelerated course with predominant musculoskeletal disease and rapid development of contractures (Figure 3).

ArIn mostly develops in linear and deep subtypes of JLS. There is a unilateral subtipe, which usually begins in childhood and results in severe deformities of extremities (Figure 4). The origin of ArIn in JLS may be of different types: caused by scleroderma changes (induration or fibrosis) in skin and periarticular tissues, arthritis itself, avascular necrosis of joints and bones. Modern techniques such as ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging are used now in pediatric rheumatology to describe structural articular lesions at the early stages of JLS.

The ArIn was studied retrospectively in 190 children with JLS, girls -128, boys-62), who were under supervision at the specialized rheumatology department of I.M. Sechenov First. Moscow Medical University for a five – year period from 2006-2011. The surveyed group consisted of children from 3 to 17 years of age, including 128 girls and 62 boys (F\M ratio 1:2).The patients with JLS were divided into groups based on the clinical forms of the disease in accordance with the preliminary classification criteria.9 At the time of examination the patients with different clinical forms of the disease had dissimilar disease duration and activity, 65% of all the patients did not receive therapy with immunodepressants.

A history of joint manifestations was obtained by standard physical examination, X-ray, MRI ( in some cases), common blood tests, antinuclear antibodies (antinuclear factor (ANF), rheumatoid factor (RF), antitopoisomerase 1 and anticentomere antibodies,antibodies to DNA, autoantibodies to collagen (Cab) types I-IV, cryoglobulins (CG), serum fibronectine (FN) and hyalyronic acid (HA) levels. Levels of Scl-70 and аnti-centromere antibodies were measured by enzyme immunoassay test using kit “Anti-Scl-70 Orgentec”, (Germany). ANF was determined by indirect immunomanufacturer. The presence of cryoglobulins in blood serum was determined with “Solar” PV 1251C (Solar, Belarus) spectrophotometer at a wavelength of 500nm in accordance with the optical fluid density difference in a buffer solution (pH 8.6), incubated for 1 hour at the temperature of 4°С and then at 37°C.The normal values are up to 0.06 optical density. Determination of type I-IV collagen antibodies in blood serum was performed with ELISA method.The test was considered positive if the negative control value exceeded. To interpret the results of the research the concept of “positive” was introduced for this test. The results were thought to be “positive” if they showed exceeding reference values in the tests with quantitative expression, presence of Scl-70 and аnticentromere antibodies in blood serum, antinuclear factor titer of 1:80 or higher.

Statistical analysis of the results was performed with the use of Statistica 6.0 software. The quantitative indices were presented as mean values±standard deviation and range of values. Quality indices were presented as an absolute number of observations and proportion (in %) of the total number.The validity of differences in the compared values was determined by Student’s t-test for interval variables. The differences were considered statistically significant at p<0.01.

According to the clinical form of JLS the patients were divided into 4 groups: 14 patients with plaque morphea, 89- linear scleroderma, 77 – generalized morphea (including 31 with unilateral form), pansclerotic in 3 patients, mixed morphea – in 7 patients (Table 1).

Clinical subtypes of juvenile localized sclerodema |

Number of patients |

Articular involvement (%) |

|

JLS |

Plaque morphea |

14 |

|

-superficial |

4 |

|

|

- deep |

10 |

1 |

|

Linear scleroderma |

89 |

|

|

- trunk\limbs |

58 |

97 |

|

- head |

31 |

3 |

|

Generalized morphea(-unilateral form *) |

77(31*) |

26(100*) |

|

Pansclerotic scleroderma |

3 |

100 |

|

Mixed morphea |

7 |

20 |

|

Table 1 Articular involvement in different clinical subtypes of juvenile localized scleroderma

Indices |

The range of absolute value |

Mean level (М+м) JLS pts (N=190) |

% of positive in JLS pts with ArIn (group IN=125) |

% of positive in JLS pts without ArIn (group II N=65) |

|

Antinuclear antibodies* (titer) |

1:80 -1:640 |

- |

56 |

3,2 |

|

Rheumatoid factor*(IU/ml) |

11-125 |

82,4+60,3 |

28,4 |

2,1 |

|

ds-DNA (IU/ml) |

0-62 |

34,5+3,6 |

2,5 |

- |

|

Anti Scl-70 antibodies |

- |

- |

8,5 |

- |

|

Anti-centromere B antibodies |

- |

- |

0,5 |

- |

|

Cryoglobulins (optical density unit)* |

0,037-0,216 |

0,051+0,037 |

27,6 |

5,2 |

|

Collagen antibodies (mkg/ml) |

I type* |

0,297-0,893 |

0,405+0,112 |

71 |

11,5 |

II type* |

0,330-1,129 |

0,551+0,161 |

62 |

12 |

|

III type* |

0,287-0,681 |

0,370+0,108 |

58 |

8 |

|

IV type |

0,151-0,577 |

0,300+0,085 |

51 |

5 |

|

Serum fibronectin* (mg/ml) |

68-264 |

124,8+41,9 |

46,5 |

14 |

|

Hyaluronic acid* (ng/ml) |

5,4 -68,4 |

15,7+16,7 |

23,7 |

8,5 |

|

Table 2 Serum antibodies profile in JSL patients with and without ArIn

Note* difference between groups statistically valid (p<0,01)

Mean age of the disease onset was seven years and six months (range 18 months – 15.5 years). As the Table 1 shows, the vast majority of surveyed patients were children with severe forms of JLS - linear scleroderma of limbs, generalized morphea (including unilateral form) and pansclerotic scleroderma. ArIn was noticed in 125 patients (65.7%), among them the 99% was in cases of linear and unilateral form of JLS. It was presented by joint pain in 25% of patients, limitation of joint movement in 62% of affected patients, mostly due to periarticular induration or tissue fibrosis, joint effusions – in 1% of ArIn. Significantly more frequently joints were affected in linear scleroderma of extremites and unilateral form. In linear scleroderma of head, contracture of temporo-mandibular joint was only in 1 case, with prolonged disease duration, for more than 10 years.

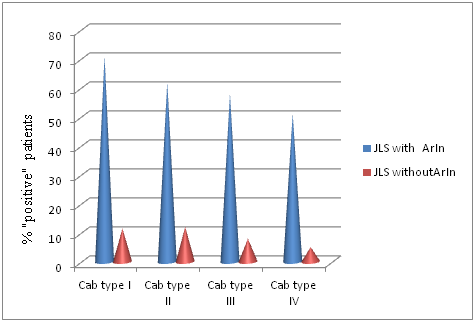

We did not find significant blood leucocytosis or elevated ESR in our series. The analysis of the data suggests that patients in both groups were “positive” for most of the required tests, except sclerodermospecific antibodies. At the same time, the absolute percentage of positive values was higher in the group I – children with ArIn. (Differences are statistically valid) (Figure 2).

The cohort study of patients showed that ANF was detected in 56% and RF in 28.4 % of patients with ArIn. The obtained data are compatible with the results of the international multicenter studies of children, in which the proportion of ANF detection in children with JSS ranges from 81% to 97%8 and it amounts to 42.3% in patients with JLS.9,10 It is known, that in scleroderma the presence ANF and RF correlates with articular manifestations of the disease. RF has been detected, as low titre, in 16 % of the patients who had JLS, and significantly correlated with the presence of arthritis.1 In adults, Ig M RF is present in 30 % of patients who have LS, particularly who have GM, and seems to be correlated with disease severity.11 According to the literature data, there is no connection between antinuclear factor detection and any clinical form of JLS.5

In our series sclerodermospecific antibodies and ds-DNA were detected in small percentage of ArIn patients and in none without it. It is no wonder, because these antibodies are mainly found in JSS. Surprisingly, the levels of CG and collagen antibodies were elevated in patients with ArIn. CG was the third most frequently detected element (27.6%) in JLS with ArIn, while its detection rate was less than 5.2% in patients without ArIn. Increased level of CG in ArIn patients confirms the role of immune mechanisms in the pathogenesis of this clinical form.12 Similar to it, the levels of FN and HA in serum had a higher detection rate in children with articular manifestations.

Summing it up, the levels of autoantibodies and markers of fibrosis were significantly higher in the patients with ArIn (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Detection rate of antibodies to type I-IV collagens in patients with ArIn and without ArIn.

Ultrasounography showed synovitis or tenosynovitis. Radiologic abnormalities in knee, hip, ankle and wrist joins were seen 8 patients with linear JSL, 5 with unilateral generalized morphea and 1- pansclerotic morphea. In 12 children joint space narrowing was detected, in 2- articular erosions. Patients with articular erosions had prolonged disease duration (more than 7 years) and were treated unadequate. MRI with contrasting visualised avascular osteonecrosis of tibia in 1 girl with unilateral scleroderma.

All the patients with ArIn received immunodepressant therapy – glucocorticosteroids (GC) orally 1mg\kilo for 6-8 weeks,then tapered and withdrawn through the 3-6 months, and methotrexate (MTX) parenterally 12 mg\sq.m. for at least 2 years. In 76% of cases of ArIn this treatment increased range of joint movements or stopped flexon contractures. Therapeutic efficacy was worse in prolonged JLS with ArIn, in case of 5 and more years without treatment.

ArIn in JLS influences greatly the outcome of the disease and social adaptation of children. The frequency of occurance of ArIn in JSL has been previously reported. In the present series of 190 JSL chidren, ArIn was detected in 65.7% of cases, mainly in linear and unilateral form of JLS. Only 25 % of affected children complained of joint pain, tenderness, or pain on joint motion. Flexion contractures of joints with disability were the main complaint. Limitation of joint movements was mostly (in 70%) due to the induration of soft tissues and skin around the joint and was reversible under therapy. In the contrary to lower percentage of joint effusions – in 1% of ArIn. Ultrasound investigation of affected joints showed slight “subclinical” -synovitis and tenosynovitis in 80% of ArIn parients. While join space narrowing by X-ray was detected in 12, articular erosions - in 2 children. In 1 girl with unilateral scleroderma MRI with contrastingdetected avascular osteonecrosis of tibia.

In our series the levels of detected autoantibodies and markers of fibrosis were significantly higher in the patients with ArIn. The detection of autoantibodies and markers of fibrosis involved in the pathogenesis of JLS is an evidence of systemic autoimmune and collagen synthesis disturbances in these patients and also determines the target points for the treatment with immunosuppressants and antifibrotic agents. According it JLS with ArIn of numerous joints could be considered as systemic form of scleroderma. Especially, it is true for the unilateral form JLS, that usually starts in childhood and leads to disability and impaired quality of life.

Contractures in JLS are mainly reversible thanks to reversibility of oedema and induration stages of scleroderma under treatment with GC and the* partly reversible (fibrotic lesions)*, while treated with MTX. Only few patients had irreversible arthritis with joint space narrowing and erosions. In JSS clinicians rarely doubt about the decision of including GC and cytotoxic drugs in the therapy. In contrast, the treatment of LJS is believed to have successful outcomes with the local use of immunosuppressive agents.

It should be emphasized that the chronic nature of scleroderma, the prevalence of linear form of the disease in children, complicated by irreversible fibrosclerotic defects of the musculoskeletal system, growth retardation of extremites encourage pediatric rheumatologists to elaborate a unified treatment protocol with GC, MTX or other antifibrotic drugs. There are few reports of successful treatment with biologic agents in resistant cases.13,14 The appropriate treatment must be started at early stages of JLS, to prevent joint contractures and severe deformities of legs and hands. Additionaly patients with ArIn need orthopedic correction (Figure 6), reconstructive surgery in adults (arthrodesis and flap surgery).

None.

Authors declare there is no conflict of interest in publishing the article.

©2018 Osminina, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.