MOJ

eISSN: 2572-8520

Research Article Volume 1 Issue 3

Department of Civil Engineering, University of Asia Pacific, Bangladesh

Correspondence: Sharmin Nasrin, Department of Civil Engineering, University of Asia Pacific, Bangladesh

Received: November 07, 2016 | Published: December 16, 2016

Citation: Nasrin S. Work travel condition by gender-analysis for Dhaka city. MOJ Civil Eng. 2016;1(3):83-91. DOI: 10.15406/mojce.2016.01.00017

This paper presents exploratory analysis of survey data to understand work travel condition by gender in the context of Dhaka, Bangladesh. Dhaka’s societal structure does not provide the degree of mobility independence to female inhabitants that is afforded to males. Therefore, it is necessary to incorporate work travel condition of male and female workers separately in transport plan and policy of Dhaka. Result indicates that gender is a key variable of work trip. Work travel conditions vary significantly between male and female workers. More interestingly, notable interaction between gender and income exists. We found that low income female workers are compelled to walk to their work place. Considering overall transport situation it can be said that if low income female workers income increase they would switch to other mode of transport to enjoy more comfortable travel options. With the increased income middle and high income female workers spend more on work trip. Middle income female workers mainly use bus for work trip, whereas high income female workers use car and three wheeler Auto-rickshaw, CNG, which are more expensive than bus. High income male and female workers do not tend to walk for their work trip. There are also significant differences in travel characteristics between male and female workers within each income group.

Keywords: travel pattern, gender and transport developing country

Dhaka is the capital city of Bangladesh, which by custom is a male dominant society. Even though a large work group consists of females, society in Dhaka does not provide the degree of mobility independence to female inhabitants that is afforded to males. Crime is another notable issue regarding mobility, almost 61% of Bangladesh’s crime occurs in Dhaka city, which contains approximately 11% of the nation’s population.1 Certain groups of trip makers, in particular females, do not feel safe, secure and comfortable on Dhaka’s transport system.2 As a result, gender issues can have significant impact on commuters’ mode choice, and should be carefully considered in the transport planning of Dhaka city.

This paper examines difference between males’ and females’ work trip making in Dhaka. The research questions addressed in the study are: Are there differences between male and female workers’ work trip making? Are there differences in work trip travel behaviour between different female income groups? A two phase survey was conducted from October 2011 to December 2012 in response to these questions. Exploratory analysis of the survey data was used as the methodological basis to understand differences between males’ and females’ work trip making. Although this study is in the context of Dhaka, conclusions from this study can potentially be generalized at least to some degree to other big cities in developing countries because of the shared feature of male dominance.

The travel patterns between male and female differs widely in developing countries.3 This difference is mainly a consequence of society and culture. Working women’s travel pattern is more complex than men in both developed and developing countries.4 Working women not only involve in outside job but also in domestic activities. These joint responsibilities make them travel more frequently than working men.

Female low income earners in Dhaka face more difficulty when travelling, as they have limited access to modes of transport other than walking.5 Female’s inadequate access to transport service is mainly because of patriarchy, poverty and policy regarding transport planning.6 In another study compared five different developing cities gender segregated travel pattern and for Dhaka city.7 He found that:

Paul-Majumder & Shefali8 in the consultant report for the World Bank Dhaka Urban Transport Project stated that in Dhaka women desire “women only” bus service.8 However, even though women only bus service was implemented it was not a big success.

Rahman9 explored the reasons for failure of ‘women only buses’ in Dhaka. He found that these bus services did not provide maximum profit as their routes and timing were not planned properly to cover all types of female bus passengers.

Zohir2 conducted a study entitled “Integrating Gender into World Bank Financed Transport Programs” for the case study of Dhaka.2 This study found that there is a disconnection between the gender enabling environment and the transport sector. Her focus group discussion revealed that even though overcrowding has been found main issue for females, practicalities regarding bus accessibility were not considered. She recommended that 25% seats in all public transport should be reserved for females only. It is also important to ensure that the seats for females are not occupied by males. Literature review on gender and transport demonstrates that gender has significant importance on transport planning. Even though many researchers have studied males and females travel behaviour none has discussed differences of travel behaviour among different group of income earners. Most of the studies generalize the difference of travel condition between men and women. This study will overcome that gap by segregating both men and women workers into different income groups and investigating their travel behaviour.

Survey design and implementation strategy

Survey design involved two main steps; sampling plan and establishing the procedure for obtaining sample data.10 Survey design for this study is divided into five steps: determine aim of survey, select sample, determine sample size, select survey medium, prepare questionnaire, and develop strategy for non-response bias. Aims of the survey were: 1) to determine the modes that commuters in Dhaka use for their home based work journeys; and 2) to determine the time, cost and distance by these modes. Two approaches were taken to recruit participants: 1) respondents approached through their employers; and 2) respondents contacted directly. Respondents, who were engaged in their usual service jobs, were contacted through their respective employer with that employer’s approval. The organizations were selected randomly from Bangladesh Business Directory.11 However, for covering wide range of workers Dhaka was divided into 4 zones and from each zone organizations and participants was selected randomly. Figure 1 illustrates Dhaka city map and 4 zones for survey. A list of randomly selected organization was generated and organizations less than or equal to 2 employees were excluded from the list. The responsible authority at the organization was contacted through email, phone or from personal visit and with their consent respondent was given questionnaires.

In Dhaka a wide range of people are engaged in domestic assistant and chauffer employment. Domestic assistants are predominantly female. They were contacted personally. These employees mainly have low income and very limited education, some being illiterate. A large sample size was obtained by this study to ensure non-biased representation of the population. A paper based survey was chosen for its simplicity and convenience for face to face interaction. With internet usage still infrequent in Dhaka, web based surveying was not a feasible option. Survey by telephone was also not considered feasible due to high cost. Glasow10 stated that survey questions should be consistent with the education level of the respondent.10 In this vein the survey was prepared bilingually in simple Bangla, which is easy to understand for most respondents, as well as English. The required completion time for the survey was 10 minutes or less.

Israel12 stated that no matter how well the sampling design is planned a poor response rate can make a study virtually useless.12 The response rate of this survey was about 90%. High response rate was ensured by conducting the survey at the presence of the surveyor. Some of the respondents agreed to participate at their most convenient time. Among those some of the respondents did not answer the whole questionnaire. To address non-response respondents were asked why they were not willing to respond. Questions were explained verbally to those who stated that the questions were difficult to understand. The only risk associated with this survey was time loss of workers. To reduce work hour loss they were proposed to be contacted during their most convenient time or during the hours when they had less work than normal hours.

Overview of survey

The survey was conducted from October 2011 and December 2011, and between September 2012 and December 2012. Samples differed entirely between these two phases. The first survey was conducted to understand whether questions were understandable to the various categories of workers. This survey was divided into a revealed preference (RP) survey and demographic questions. In the RP survey, respondents were asked how they usually travelled to work, travel time, travel cost, and any problems they faced while on work trip. Accordingly second survey was also divided in the same manner.

A large sample size was obtained for this study to ensure good representation of the total population. The first and second surveys included 426 subjects and 462 subjects respectively. In both survey’s respondents were asked limited demographic questions: age, income, and education. Table 1 lists the demographic characteristics of the survey data. To check the representativeness of the survey data some of the variables were compared with other sources. The ratio of male to female workers of the survey data is almost the same as the World Bank data.13 According to STP data most people (96%) in Dhaka fall into the low and medium income groups.14 Survey data also closely reflects this, although the higher income proportion is slightly higher, which is at least partially attributable to inflation. However, comparison of modal share with STP data shows that except car mode, percentages of modal share of other modes are similar.

Demographic Characteristics |

First Phase Survey |

Second Phase Survey |

Comparison of Survey Data with other Sources |

|

Gender |

Male |

62% |

65% |

67%1 |

Female |

38% |

35% |

33%1 |

|

Age |

Age 0-18 |

3.0% |

5.0% |

|

Age 19-25 |

14.0% |

18.0% |

|

|

Age 26-35 |

38.1% |

46.0% |

|

|

Age 36-45 |

28.5% |

23.0% |

|

|

Age 46-55 |

12.7% |

4.0% |

|

|

Age 56-65 |

3.4% |

3.0% |

|

|

Age 65 above |

0.3% |

1.0% |

|

|

Income |

Income Low(<12,500 BDT or approximately A$<180) |

43.0% |

40.0% |

45%2 |

Income Middle (12,500 BDT-55,000 BDT or approximately A$180-A$785) |

47.0% |

43.0% |

51%2 |

|

Income High (>55,000 BDT or >A$785) |

10.0% |

17.0% |

4%2 |

|

Education |

No certificate |

22.0% |

21.0% |

|

Primary |

14.0% |

8.2% |

|

|

Secondary |

5.0% |

4.8% |

|

|

Higher Secondary |

7.0% |

3.3% |

|

|

Graduate |

23.0% |

21.4% |

|

|

Post Graduate |

28.0% |

41.1% |

|

|

No answer |

1.0% |

0.2% |

|

|

Modal Share |

Bus |

45% |

47% |

Transit 37%2 |

Car |

9% |

7% |

Motorized non transit 25%2 |

|

Rickshaw |

17% |

14% |

Rickshaw 25%2 |

|

CNG |

5% |

0.22% |

|

|

Walk |

23% |

24% |

Walk 37%2 |

|

Other (Laguna, battery operated CNG, Tempo, motorcycles, bicycles, taxi etc.) |

2% |

7% |

|

|

Table 1 Percentage of Survey Data across Demographic Characteristics

1The World Bank (2007); 2 The Louis Berger Group and Bangladesh Consultant Ltd (2004)

Survey data analysis

To understand work travel condition of male and female workers, exploratory analysis was carried out based on income. Three income categories have been used for analysis: low (0 BDT -10000 BDT, approximately US$ 0- US$ 130), medium (10001 BDT-30000 BDT, approximately US$ 130- US$ 390) and high (above 30000 BDT, approximately above US$ 365). The income category is divided based on Strategic Transport Plan (STP) income segregation (14). STP is the most comprehensive transport planning document for Dhaka and documents long term transport planning from 2004 to 2024. However, in STP low income and middle income range is respectively from 0 BDT to 12,500 BDT (approximately US$0 - US$160) and from 12,500 BDT to 50,000 BDT (approximately US$160-US$650). Because of data unavailability exactly same income segregation was not possible for exploratory analysis.

Income impact

The main modes of transport for work trip are walk, bus, rickshaw, CNG (auto-rickshaw, local name is CNG as it is driven by CNG), and car. Also smaller version of auto-rickshaw named as mishuk also used by the worker. As very few respondents chose mishuk for their work trip this study aggregated mishuk with CNG users. Very few respondents also chose Laguna/I, battery operated CNG (banned by government), tempo, motorcycles, bicycles, or taxi for their work trip. These modes were aggregated into the “other” category. Low income earners are dependent on cheap modes of transport whereas those who are high income earner can spend more money on mode of transport for their work trip and rely on more comfortable but expensive transport options, such as car, CNG etc. Income and choice of mode of transport are closely related. Almost 75 percent of respondents with income less or equal to 500 BDT (approximately US$6.50), walk everyday to their work place. Most low income earners stated that they walk to their work place. Footpath conditions in Dhaka are very poor such that none of the respondents who walked stated they choose to walk willingly; rather, they stated that they were forced to walk because of their inability to pay for vehicular travel. Figures 2A-2F illustrate percentages of usage modes by different income categories female and male workers. Figure 2A shows that approximately three quarters low income female workers walk to work, while about 20 percent use bus, with access mode mostly walking. Figure 2B shows that maximum percentages of low income male workers use bus for their work trip. None of the low income male and female workers used car for their work trip. CNG use also significantly low among both low income male and female workers.

Almost two thirds of middle income female workers travel by bus with rickshaw as a dominant access mode Figure 2C. Only 3 percent of middle income female walked to work, which can be attributed to very poor pedestrian facilities. Modest proportions of middle income female workers travel by car, CNG or other. From the Figure 2D it can be seen that about one half of middle income male workers travel by bus with walking as main access mode and another one half travelled by Rickshaw. Modest proportions of middle income male workers travel by bus, car, CNG or other. A very small percentage walks. The main difference between middle income male and female workers is that all the way rickshaw and using bus with access modes as walk are more dominant among middle income male while rickshaw use as an access mode is more dominant among female workers. More percentage of middle income female workers use car and CNG compared to middle income male workers. Figure 2E & 2F show that most of the high income male and female workers used car, rickshaw, or CNG as their mode of transport. However proportions of car users among high income workers are the maximum compared to other income categories. Moderate proportion of high income male workers used buses including access mode by walk or by rickshaw. Very small percentage of the high income male and female workers travelled to their work place by foot. However, survey response showed these respondents lived very near to their work place and they preferred to walk for health reasons.

Gender and income interaction

Table 2 lists the descriptive statistics of all income category female and male workers. On average low income female workers travelled 4 km for their work trip and their in-vehicle time was about 8 minutes. Most low income female workers walked with average walk time 35 minutes and on average spent 2 BDT (approximately US$ 0.03) for their journey. In contrast low income male workers’ average in-vehicle time was 30 minutes, and travel cost was 17 BDT (approximately US$ 0.22). These differences highlight different travel characteristics between low income male and female workers. On average middle income female workers spent about 75 minutes inside a vehicle. Their cost of travel was on average 51 BDT (approximately US$ 0.70) and they travelled about 6 km for work trip. On contrary result shows that on average for middle income male workers in vehicle time was 65 minutes and average cost of their trip was 34 BDT (approximately US$0.50). Average distance they travelled was about 7km. This highlighted that, even though male and female workers travel about same distance, females spend more in-vehicle time and money for their work trip. On average high income female workers spent about 50 minutes inside the vehicle. They spent on average about 68 BDT (approximately US$0.90) and travelled about 5 km distance for their work trip. On the other hand high income male workers spent more in vehicle time and spent more money for their work trip. Average travel distance of high income male workers was 8 km. High income female workers travel for less time and shorter distance but spend about the same money on transport as do males.

Table 2 presents the average travelling distance for work trip for different income categories. The table shows average travelling distance for different income categories varies from 4 to 7 km. Overall average travelling distance for all is about 6 km. It can be concluded that both low income men and women workers live near to their work place compared to high and middle income workers. Middle income and high income workers live further from the work place compared to low income workers. Figure 3A & 3F illustrates the average cost for different income categories male and female workers. Figure 3A shows for low income female workers the expenditure on travel is skewed, with almost three quarter spending nothing (those who walk), and almost 20 percent spending the minimal amount of 1-10 BDT (approximately US$0.01-US$0.15). Other cost range were each negligible in proportions. Figure 3B shows that for low income male workers there is a fairly wide distribution of expenditure on travel. Almost 20 percent spend no money on their work travel, most likely walking. Only about 2.9 percent respondents spent the maximum amount of money.

Income Status |

Variables |

Female |

Male |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Mean |

Median |

Mode |

S.D |

Min. |

Max. |

Mean |

Median |

Mode |

S.D |

Min. |

Max. |

||

Low Income |

In-Vehicle Time (Minute) |

18 |

0 |

0 |

18 |

0 |

120 |

22 |

20 |

0 |

29 |

0 |

135 |

Walk Time to Work Place (Minute) |

46 |

30 |

60 |

23 |

0 |

60 |

38 |

0 |

0 |

17 |

0 |

60 |

|

Cost for Work Trip (BDT) |

8 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

0 |

55 |

7 |

14 |

0 |

22 |

0 |

120 |

|

Distance Travelled for Work Trip (km) |

3 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

11 |

3 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

1 |

20 |

|

Middle Income |

In-Vehicle Time (Minute) |

46 |

75 |

90 |

45 |

0 |

250 |

45 |

60 |

60 |

45 |

0 |

180 |

Walk Time to Work Place (Minute) |

10 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

15 |

17 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

15 |

|

Cost for Work Trip (BDT) |

45 |

40 |

25 |

44 |

0 |

215 |

28 |

30 |

40 |

22 |

0 |

100 |

|

Distance Travelled for Work Trip (km) |

5 |

5.7 |

5 |

4 |

1 |

20 |

5 |

5 |

3 |

5 |

1 |

25 |

|

High Income |

In-Vehicle Time (Minute) |

32 |

45 |

30 |

33 |

5 |

120 |

53 |

60 |

60 |

32 |

10 |

195 |

Walk Time to Work Place (Minute) |

6 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

0 |

15 |

8 |

0 |

0 |

1.6 |

0 |

15 |

|

Cost for Work Trip (BDT) |

47 |

30 |

30 |

77 |

0 |

250 |

53 |

50 |

50 |

61 |

0 |

400 |

|

Distance Travelled for Work Trip (km) |

3 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

0.5 |

12 |

7 |

7 |

7 |

5 |

1 |

25 |

|

Table 2 Descriptive Statistics of Female and Male Workers

*BDT is Bangladeshi Currency

Unlike low income female workers, middle income female workers could afford to pay for transport for their work trip Figure 3C. The greatest percentage of respondents spent in the range of 21-30 BDT (approximately US$0.30-US$0.40). As walking facilities in Dhaka are very poor, when respondents have ability seldom they choose to walk. Most middle income male workers spent in the range of 30-50 BDT (approximately US$0.40-US$ 0.70) (Figure 3D). For some of the middle income male workers, their work trip did not cost anything as they walked. Distribution of cost is normal for both middle income male and female worker. The greatest proportions of high income female workers spent in the range of 21 to 30 BDT (approximately US$0.30- US$0.42) Figure 3E and high income male workers spent in the range of 41 to 50 BDT (approximately US$0.60- US$0.70) (Figure 3F). Very small proportions of them spent above 50 BDT for their work trip.

Figure 4A-4F illustrates distance travelled by different income categories male and female workers. Both low income male and female workers predominantly travel between 1 and 5 km. A slightly higher percentage of low income females than low income males travel between 6 km and 10 km. Figure shows that most of the middle income female and male workers travelled a maximum 10 km for their work trip. There is more dispersion in travel distance amongst middle income male than female worker. Most of the high income workers surveyed travelled in the range of 1 to 10 km distance for work trip. More percentages of high income male workers live far away from the work place.

Comparison of different travel attributes of work trip

Different travel attributes for work trip are compared by normalizing the data. Normalization of data means adjusting values measured on different scales to a notionally common scale.15 Normalized values allow the comparison of corresponding normalized values of different datasets. Therefore, data has to be converted into unit less measurement. Data normalization is done based on linear algebra by treating the data as a vector in a multidimensional space.16 According to Salkind16 in this normalization process data vector is transformed into new vector whose norm (i.e. length) is equal to one. Norm of a vector measures its length equal to the Euclidian distance of the endpoint of this vector to the origin of the vector space. Based on Pythagorean theory norm is computed as the square root of the sum of the squared elements of vector. For example, Equation 1 denote Y vector, Equation 2 calculates norm of vector Y, Equation 3 normalize data vector Y with norm.

Eq. 1

Eq. 2

Eq. 3

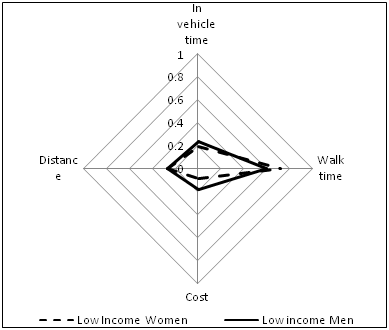

Figures 5-7 illustrate the comparison of average in-vehicle time, cost, distance, and walk time for low, middle and high income male and female workers respectively assigned in normalized scale. Equation 1, 2 and 3 were used for normalizing data. Apart from high income male workers, workers across all income categories travelled same distance on average. In normalized scale walk time is the maximum for low income female workers (0.7) followed by low income male (0.6) and middle income male (0.3) workers. Compared to them walk time is low for middle income female (0.2) and high income male (0.09) and female workers (0.1). In-vehicle time is least for low income female workers (0.2) followed by low income male workers (0.19). Average walk time is the maximum and in-vehicle time is least for low income female because they are mainly walking to their work place. In contrast in-vehicle time is more for middle income female (0.5) and high income male (0.6) and female (0.34) workers because they seldom prefer to walk due to insufficient walking facility instead take any mode that is affordable to them for work trip. Again for travelling same distance for work trip high income workers spend maximum (0.59 for male and 0.52 for female) whereas low income workers spend least (0.19 for male and 0.08 for female). Higher income category workers are at the higher end of normalized scale compare to low income category workers because those with higher income tend to choose any vehicle instead of walking to their work place.

Exploratory analysis of survey data highlighted that worker’s travel condition varies between men and women. Even though, all income category workers on average travelled 6 km distance for work trip, there is wide range of spending for work trip based on income. Low income workers spend least for work trip and middle and high income workers spend more money for work trip. When women workers have increased income they usually switch to better options. Unlike low income female workers middle income female workers spent more compared to middle income male workers. High income female workers have more ability to own private vehicle which gives them the maximum comfort, flexibility, safety and security. High income male and female workers spent about same amount of money. Usually a higher percentage high income female workers use car compared to male workers.

Our analysis shows low income female workers are the most unprivileged group of travellers in Dhaka. Most of the low income female workers stated that they cannot afford transport for going to their work place. The workers who travelled to their work place on foot stated many problems, such as bad road condition; less space for walking; bad drainage facility etc, for walking. Still most proportion of low income female workers walked to work place as they did not have any other choice other than walking to their work place because of their financial constraints. Low income male workers are more able to afford for their work trip. This can be explained as most of the male workers are at the higher end of low income category. Another explanation can be drawn because of cultural reasons with the limited income low income female workers tending to save more money for their family rather than spending for their own comfort. Most of the low income male and female workers live very close to their work place. So overall it can be said low income female workers’ work trip is different from male workers with respect to chosen mode, and cost even though they were travelling about same distance. In both surveys low income female workers respondents stated that they have limited ability to choose any modes of transport for travelling to their work place.

From the analysis it can be understood overall female workers are more vulnerable than male workers while travelling to their work place. In spite of absence of safety and security and proper pedestrian facility mostly female workers walk to work place when they have financial constraints. In Dhaka pedestrian facilities are very poor due to poor road condition and lack of safety and security. It is obvious when there is so many problems faced by pedestrians, they do not walk willingly instead they do so forcedly. Women workers who can afford any type of mode of transport tend not to walk to the work place. When female workers have ability to pay for buses when they live far away from work place of course they use buses instead of walking to their work place. Not only as pedestrians, have female workers faced challenges with the unfriendly situation while travelling by bus as well. Bus users’ main problems were overcrowding; non availability of enough seats; and high fare compared to service and distance. Some of the female respondents’ of bus users stated the male co-passengers, drivers’ attitude towards them were not good and some female passengers also complained that in many occasion they are abused by some male passengers. In response of problems of bus users some of the female passengers’ reaction is “…. Sometimes we don’t even can get into buses. In spite of availability of seat, bus helper tells that there is not seat inside buses. They push us so that we cannot get into buses.” Usually in Dhaka helpers of bus do not want to take more female passengers because they cannot squeeze themselves into less space as female passengers do not want to be touched by male passengers. Government has policy that at least 9 seats have to be reserved for female passengers. However, many times these seats are occupied by male passengers. Survey response also showed that female passengers do not like to have their personal space compromised by male for cultural reasons. In Dhaka waiting time for bus is high and condition for buses is also bad. Female bus passengers usually wait on roads for buses. They sometimes find this very difficult especially at night.

Using personalized public transport, such as rickshaw and CNG, not only increases the flexibility of workers but also increase safety and security while travelling to work place. Therefore, female workers who can afford, choose personalized public transport. However, travelling by personalized public transport is costly, unsafe, insecure and sometimes unpredictable. Personalized public transport users sometimes become victims of hijackers. Bad road condition and unskilled drivers often cause severe accident while travelling by personalised public transport. Female rickshaw user’s common concern was banning rickshaw use from certain roads without prior instruction and without implementing alternate modes. They also told that sometimes without any prior instructions suddenly Government do not allow rickshaws to enter into some roads; this not only cause hassle but also increase their travel time as then they have to take different route or have to wait for different mode of transport. Because of income constraints not all female workers can own a private vehicle. If female workers have ability, they choose better and expensive mode of transport. This is mainly because better and expensive mode of transport can give them a greater sense of security and comfort. However, this attitude is not highly prevalent among male workers.

Analysing survey data showed that travel pattern differs between different income male and female workers. Travel pattern greatly differs between different income female workers. These differences should be incorporate into transport planning for Dhaka. In the future research to understand the magnitude of impact of gender and income mode choice model will be calibrated with the RP data. The model result will help for policy formulation to improve the transport situation in Dhaka.

Authors would like thanks to workers and employers in Dhaka who participated in the survey for this research.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

©2016 Nasrin. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.