MOJ

eISSN: 2574-9722

Research Article Volume 6 Issue 2

1Department of Biology, Payame Noor University, Iran

2Department of Pilot Biotechnology, Pasteur Institute of Iran, Iran

3Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine Institute, Islamic Azad University, Iran

Correspondence: Seyed Mohammad Atyabi, Department of Pilot Biotechnology, Pasteur institute of Iran, Tehran, Iran

Received: January 08, 2021 | Published: March 9, 2021

Citation: Soleimani S, Nazem H, Fazilati M, et al. Survey differentiation of mesenchymal stem cell to chondrocyte using synovial fluid and cold atmospheric plasma treated nanofibrous pcl substrate. MOJ Biol Med. 2021;6(2):52-56. DOI: 10.15406/mojbm.2021.06.00129

Tissue engineering has developed strategy for the repair and regeneration of a variety of tissues. The demand for effective treatment strategies of cartilage cause to autologous human Mesenchymal stem cells (hMSC) used for the repair of cartilage defects. In this study effect of some factors on human MSCs for differentiation to chondrocyte were surveyed such as Present of Poly Ɛ-caprolactone (PCL) nanofibrous scaffold and cold atmospheric plasma (CAP), also effect and amount of synovial fluid were evaluated. In this experimental study cell culture for differentiation assay performed in 6 well pellets by DMEM high glucose medium with a supplement of 10% FBS and synovial fluid 5% and 10% of medium add to pellets for 21 days. Total cellular RNA extracted was used for analysis by RT-PCR. Alcian blue staining confirmed the chondrogenic differentiation. MTT assay results in this study showed that the cells proliferation gradually increased from 1st day to 21st days on the electrospun nanofibrous scaffold. Cellular attachment and proliferation of hMSCs showed higher rate on PCL substrate, modified with Helium cold atmospheric plasma, compared to the unmodified and control group at the first day to 21st days. Chondrogenic differentiation confirmed by alcian blue staining, and show high degree of conversion to the chondrocyte. MTT assay and the expression of chondrogenic specific genes Collagen type П and Has-2 in comparison with control groups demonstrated cell survival ability, proliferation and cell differentiation by synovial fluid.

Keywords: mesenchymal stem cells, chondrogenic, differentiation, synovial fluid, cold atmospheric plasma, nanofibrous

The main goal of tissue engineering is to reconstruct or fabricate tissue or a healthy body to replace unhealthy tissues or repair damaged tissues of a patient. Limited capacity of adult cells of a tissue in terms of cell division and their proliferation and differentiation into differentiated cells and especially the lack of sufficient an absorption of these cells in the laboratory are their limitations in tissue engineering. Three parts of the formation of a tissue in tissue engineering are Cell type, scaffold, and growth factors.1 Therefore, tissue engineering involves the separation of special cells and Specifics of the appropriate cell source for growth and proliferation in three-dimensional spots under appropriate in vitro cell culture conditions. Finally, place this collection at the right place in the patient's body and leads to the formation of new tissue in the scaffold. Use of appropriate cellular sources, especially those obtained from the patient cause to reduce the immune system problems at a large extent.2 Stem cells are undifferentiated cells that have the property of self-renewal and the production of various types of specific cells. From adult stem cells, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are good sources of tissue engineering.3 These cells are easily derived from various tissues such as bone marrow, fat tissue, and the like and without loss of capacity and self-renewal, they are cultivated in vitro. Ultimately have ability to differentiate into cells such as chondrocytes, adipocytes and bone and hepatocytes.4 Tissue engineering combines the fields of cell biology such as engineering, material sciences, and surgery to provide new functional tissues using living cells, biometrics, and signaling molecules. At last decade this discipline has more expanded, and numerous research groups focusing on the development of these strategies for the repair and regeneration of a variety of tissues.5,6

Articular cartilage is a good purpose for tissue engineering strategies because it has been well evidence that harm to articular cartilage, without direct access to a significant source of repairing cells, is not self-healing. HMSCs derived from bone marrow and adipose tissue, have ability to apply to a range of ancestry including condrogenic and osteogenic lines.7 Some of research attempt are directed to the isolation of progenitor cells and Understanding the Mechanisms participating in their chondrogenic differentiation. Protocols for the isolation and mitotic procreation of adult human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells and the specific culture conditions developed for their chondrogenic differentiation.8-10

Polyesters, such as polylactic acid and polyglycolic acid, used in biological planting and tissue repair for several decades. These polymers are now used as copolymers. Generally, scaffolds such as polylactic acid with glycollide and polycaprolactone are used in medicine. The hybrid scaffold of polycaprolactone polyvinyl alcohol with chitosan used in tissue engineering and bio-implantation.11,12 Poly (e-caprolactone) (PCL) is one of the favorable synthetic biomaterials, because it has many comprehensive properties like: , flexibility and mechanical strength, biodegradability, biocompatibility.13,14 Although bio-substrate provides favorable microenvironments for cell seeding, but hydrophobic nature of PCL gives rise to low cell loading in the initiatory step of the cell culture leading to less migration, cellular adhesion, and cell proliferation.13,15 Cold Atmospheric Plasma (CAP) is an ionized gas which is also made of electrons, photons, positive and negative ions, atoms, free radicals and non-excited or excited molecules that are related to forth state of matters. CAP treatment results in physical and chemical changes by introducing new chemical functional groups, progression in surface permeability and hydrophilicity.15 To improve the biocompatibility, PCL substrate was selected and treated with O2 plasma technique. Pure helium gas ignited in a plasma chamber induced the bombardment of a homogeneous compound of charged particles, such as electrons, ions, excited molecules, and free radicals species on the polymer surface.15,16

Synovial fluid (SF) lubricates articular joint surfaces, feed articular gristle cells, also act as a shock absorber and contains growth factors like TGFβ-1.17,18 Hyaluronic acid (HA) is an important component of synovial fluid, that it is secreted by synoviocytes, are glycoproteins and protease inhibitors.16 It has been reported that modification of PCL nanofibers with CAP, improve cell attachment, adhesion, proliferation and viability on the nanofibrous substrate. In previous research cell attachment studied on PLGA using fibroblast and osteoblast cell adhesion compared on modified PCL.11,12 Also effect of CAP on cell viability evaluated and recently chondrogenic differentiation of HMSCs induced by synovial fluid on micro mass pellet assessed. In this study the effects of synovial fluid at culture medium on CAP treated PCL nano- fibers (as bioactive nano-fiberuse substrate) for hMSCs differentiation to chondrocyte were evaluated.

In this experimental study, the hMSCs were obtained from the Cell Bank of Institute Pasteur, Iran. PCL was purchased from Sigma Aldrich, Germany. dimethylthiazol diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), (Sigma) DMEM (Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium, Gibco), FBS (Fetal Bovine Serum, Gibco), Pen/Strep (Gibco, 100U/ml), Trypsin/EDTA 0.025% (Gibco,) were purchased. Synovium was taken from the knee of arthritic patients undergoing arthroplasty from loghman hakim haspital. Nanofibrous PCL were made by electrospinning method. PCL (12.5Wt %) was dissolved in (60:40 ratio of) acetic/formic acid for 24hours and mix by stirring. The polymer solution was loaded into a syringe fitted with a needle. Polymer solutions were injected into the needle tip using a syringe at a flow rate of 0.9 ml/h; in a drum collector covered with the aluminum sheet by applying (13-27kv) voltage.19 He2 plasma treatment of electrospun PCL nanofibrous substrates was placed in cell cultured pellet and subjected to plasma discharge for 45s with 13kv.

Cell viability of hMSCs tested at 24, 48, 72 h, 14 and 21 days by MTT assay. The absorbance values of formazan solutions, obtained from the above given substrates, were Measured using an ELIZA reader at 520 nm. Cell culture for differentiation assay performed in 6 well pellets by DMEM high glucose medium with supplement of 10% FBS by adding synovial fluid 5% and 10% of medium that changed twice a week in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air, 5% CO2 at 37 °C for 21days. Total cellular RNA was extracted from cultured cells, using the guanidine thiocyanate extraction method described by Chomczynski and Sacchi. These RNA preparations were used for analysis by RT-PCR. Relative quantification of mRNA expression of hyaluronan enzymes (Has-2) and collagen type П was performed. Hyaluronan synthesis, collagen type II gene and Beta-Actin genePrimer showed in below Table 1.20 cDNA was generated by using a cDNA reverse-transcription kit. The PCR reaction performed at 94°C5min for denaturation, and 30 cycles at 94°C 45s, 60°C 45s, and 72°C 45s and final extension at 72°C for 5min. The PCR products (3µl) were electrophoresis in a 1.5% agarose gel containing safe stain, and the resulting bands were visualized by UV transillumination. Alcian blue staining confirmed the chondrogenic differentiation of MSCs.

|

beta-Actin |

5-GGCACCCAGCACAATGAAG-3 |

|

5-CCGATCCACACGGAGTACTTG-3 |

|

|

Collagen type II |

5 -CCGCCGCTTCACCTACAGC-3 |

|

5-TTTGTATTCAATCACTGTCTTGCC-3 |

|

|

Has-2 |

5-CAGACAGGCTGAGGACGACTTTAT-3 |

|

5-GGATACATAGAAACCTCTCACAATGC-3 |

Table 1 Primer Sequence for, 2Beta-Actin gene, Collagen type П and has-2.18

Statistical analysis

The experiments were performed in triplicate and data were evaluated by a Dunnet one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using software SPSS version 18. Data reported as the mean value with the standard deviation of ± 0.5.

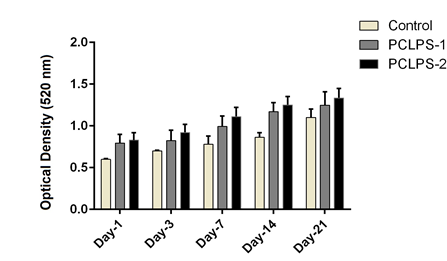

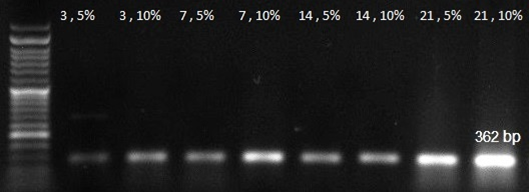

HMSCs cultured for 21 days on PCL scaffold at present and absent of CAP and different amount of synovial fluid carried out. MTT test for cell viability and mRNA expression for differentiation were assessed. MTT assay results in this study showed that the cells proliferation gradually increased from 1 day to 21 days on electrospun nanofibrous scaffold. MTT test for different conditions of cell culture showed at Figure 1 and Figure 2. Cellular attachment and proliferation of hMSCs on PCL substrate modify with He2 plasma, showed higher rate compared to the unmodified scaffold and control in the first day. These results confirmed that modified nanofibrous PCL by He2 plasma has effect on cell proliferation, viability and differentiation due to rough surface of scaffold. For hMSCs, the cell proliferation gradually increased on PCL nanofibrous from 1 to 14 days. But from 14-21 days there has been a downward trend in growth and proliferation. It’s may be due to differentiation state. RT-PCR analyses: An expression analysis for the known chondrogenic markers has-2 and collagen type П genes using RT-PCR was performed for hMSCs differentiation. In this manner, we showed that has-2 and collagen type П were induced during the course of hMSCs differentiation into chondrogenic lineage. In present of PCL substrate and treatment with cold atmospheric plasma and adding 5% and 10%synovial fluid increased collagen type II expression at days 14 and 21, respectively, when compared with the cells cultured in the control groups. Collagen type П gene expression in primary days was low but increase piecemeal that show in Figure 3. Has-2 gene expression is lately and expressed at days 14 and 21 that show in Figure 4.

Figure 1 MTT test for cell proliferation at 1, 3, 7, 14 and 21 days at different conditions.

Control: PCL: poly caprolactone, PCLP: poly caprolactone + plasma.

Figure 2 MTT test for cell proliferation at 1, 3, 7, 14 and 21 days at different conditions.

Control: PCLPS1: poly caprolactone + plasma + synovial fluid 5%, PCLPS2: poly caprolactone + plasma + synovial fluid 10%.

Figure 3 RT-PCR analysis result for collagen 2 gene expression at 3, 7, 14, 21 days in 5% and 10% amount of synovial fluid on modified PCL.

Figure 4 RT-PCR analysis result for Has-2 gene expression at 3, 7, 14, 21 days in 5% and 10% amount of synovial fluid on modified PCL.

Alcian blue staining confirmed the chondrogenic differentiation of stem cells. High degree of conversion to the chondrocyte observe at 14 and 21st days on modified PCL, with 10% synovial fluid that showed in Figure 5. The A image is Alcian blue staining for 14 days in 5% synovial fluid and B is for 10% amount of synovial fluid on modified PCL. The C image is Alcian blue staining for 21st days in 5% synovial fluid and D is for 10% amount of synovial fluid on modified PCL.

Cartilage differentiation can be done in several different ways, each of which has its own problems.21 A method for solving chondrogenesis complexities is to study simple laboratory systems. HMSCs have the ability to differentiate into multiple connective tissues, including bone, tendon, ligament, cartilage, fat, and muscle.22 A number of scientists have reported in vitro chondrogenic differentiation of hMSCs in a micromass pellet culture with the defined medium containing bioactive factors such as BMP-6, TGF-β and dexamethasone.23 Several research reported effect of different scaffold role in chodrogenesis such as nanofibrous PLGA and PCL.10,14 In this study we demonstrated that synovial fluid of the human's knee has an effective potential to induce chondrogenic differentiation of hMSCs on PCL treated with CAP.24 Treatment with electromagnetice wave has been received attention for bone tissue engineering due to its confirmed clinical application and osteogenic and condrogenic effects.25 Cell attachment is so important in tissue engineering. Better cellular attachment may be related to the surface hydrophilicity. Presence of polar functional group change hydrophobic surface to a hydrophilic. Unmodified PCL has hydrophobic properties. Using cold atmospheric plasma for surface modification of biomaterial has many adventage like produced chemical functional groups and improving hydrophilicity.19 Coupling factors that accumulate inside the scaffold increase connectivity and cell migration henc they reduce the duration of the reconstruction and the length of the period. Accurate control over the structure of the scaffold provides minimizes side effects such as inflammation and early enzymatic degradation.26 These scaffolds are not toxic to the body and do not cause an immune response.27

The MTT assay results demonstrate the PCL modifying byHelium CAP cause to increasing of surface roughness and hydrophilicity hence induced cell adhesion, cell attachment and proliferation. Synovial fluid acts as a model for finding effective combinations of differentiation factors and deserves further research on its components and their potentials to induce chondrogenesis.28,29 MSCs are genetically stable after limited passage but several alternation occure at epigenetic level. Increased histone acetylation leads to decrase in expression of pluripotency genes and up regulation of condrogenic genes.30,31 RT-PCR analysis result for collagen 2 and Has-2 gene expressions at 3, 7, 14, 21 days in 5% and 10% of medium synovial fluid show that collagen 2 gene expressed increased from 3 to 21 days but Has-2 gene expressed at 14 and 21 days. And 10% of synovial fluid has more effect on differentiation to chondrocyte at the present of CAP treated PCL. HAS-2 is the major expressed isoform in chondrocytes and cartilage, there are appreciable levels of HAS-1 in contrast to reports by Nishida et al.32 The nano-structured PCL scaffold acted as a positive factor for cell growth. These findings confirm the results of the adhesion test and all of them were due to electrospun nanofibrous. Also, cell proliferation and cell viability was measured using MTT assay and showed that, the electrospun nanofibrous had better performance for suitable cell behavior. Scaffold topography strongly effects on cell morphology, and impressive on cell adhesion, proliferation, and gene expression.33 These findings underline the fact that SF contains factors such like hyaluronic acid and insulin which promotes and enhances the development of cartilage synthesis by mesenchymal stem cell and progenitor cells. SF also contains factors of the TGFβ sub family, FGF (fibroblast growth factors) and BMP (bone morphogenetic proteins), which are able to induce the chondrogenic differentiation.27 However, the stimulation with synovial fluid was not sufficient to detect some aggrecan or type II collagen on protein level, but can detect it on mRNA level.34-36 Synovial fluid has a major potential to induce chondrogenic differentiation. The concentration of hyaluronic acid in synovial fluid is approximately 2–4 mg/ml. Prolactin hormone is one of the efficient factors of human synovial fluid, which integrates the growth and chondrogenic differentiation of hMSCs.37 Synovial fluid also containsTGF-β1 and insulin in high concentration (100 µIu/ml) also contains glucose and protein that cause to cell proliferation and differentiations.17,24

In this study, our obtained results from MTT assay, alcian blue staining image and the expression of chondrogenic specific genes in comparison with control groups demonstrated cell survival ability, proliferation and cell differentiation by synovial fluid on CAP treated PCL. It is suggested that this method can be used for induction of chondrogenesis.

We wish to thank personal of Department of pilot biotechnology, Pasteur institute of Iran- Tehran and Loghman hakim hospital- Tehran trust for them effort and help.

None.

None.

©2021 Soleimani, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.