MOJ

eISSN: 2573-2935

Research Article Volume 5 Issue 3

National University of La Pampa & National University of Rio Negro, Argentina

Correspondence: Luciano Levin, Deputy Investigator UNRN-CONICET, Associate Professor UNLPam, National Universityof La Pampa & National University of Rio Negro,, Villegas 360, San Carlos de Bariloche, Argentina, Tel +54 294 4428225, +54 9 11 50411508

Received: January 26, 2018 | Published: May 21, 2018

Citation: Levin LG. Addictions as a social construction: knowledge’s, public positioning, and state implementation of treatments. MOJ Addict Med Ther. 2018;5(3):106-120. DOI: 10.15406/mojamt.2018.05.00103

This paper describes and analyzes various ways in which drug addiction has been constructed from different cognitive perspectives, each of which has been conceptualized in terms of:

In this work we assume that the emergence of a problem of these characteristics, contingent decisions about how addiction is treated, what types of medical treatments should be implemented, where and by whom, are decisions that result from the interaction between different social actors that mobilize institutional mechanisms and knowledge that shape the interests of the parties involved and public opinion. Then we systematized each of the elements that have been identified in the respective conceptualizations, to show how the analysis of these dimensions allows us to explain the current structuring of the problem - social, public and knowledge.

Keywords: addiction, medicalized behaviors, deviant behaviors, neurobiological view, psychologists

In this work we assume that the emergence of a problem of these characteristics, contingent decisions about how addiction is treated, what types of medical treatments should be implemented, where and by whom, are decisions that result from the interaction between different social actors that mobilize institutional mechanisms and knowledge that shape the interests of the parties involved and public opinion. Then we systematized each of the elements that have been identified in the respective conceptualizations, to show how the analysis of these dimensions allows us to explain the current structuring of the problem - social, public and knowledge - in the local context.

Ways to conceive addiction

Four perspectives have been analyzed based on which the consumption of substances is problematized: Criminalizing conceptions, which conceive the problem in terms of the consumption of prohibited substances as "deviant practices" with respect to established norms.1–4 This conception has its axis in the substances, which they define as illegal. The users of drugs are, therefore, criminals and consequently the way in which they seek to intervene is the repression of the activities related to the use of substances and the confinement of the people who participate in these activities. The knowledge involved in this conception is of a quantitative nature. They are used as a rhetorical strategy to validate this vision and not as a constituent element in its construction. That is, knowledge is produced ad-hoc and is not the structuring variable of this conception, which is eminently ideological. It counts the production of drugs, the number of consumers and other variables that support the idea that the production of illegal substances is increasing and the number of consumers as well. The behaviors that are included in the field of action of this conception are classified as criminal behaviors and, therefore, deviant.

Biological conceptions, represented by the neurobiological view, which constructs the problem in terms of the neuronal receptors that make up a "diseased brain".5–9 The subjective conceptions, represented mainly by psychoanalysis, which conceives the problem in terms of the construction of subjectivity and where the consumption of certain substances forms the symptom of a dysfunctional psychic apparatus.10–12

This conception interprets the addictive phenomenon in different ways, but all of them have the common denominator of responding to a way of conceiving the functioning of behavior based on the existence of an immaterial psychic apparatus over which one can intervene subjectively, mainly by means of the word, whether it is the analyst's word or the addict's word. Unlike the biologizing conception, the central question here is about the causes that lead the subject (not the society) to consume, and that is the main object of the analytic intervention. The substance loses its centrality with respect to other conceptions, and becomes almost an excuse to treat the symptom of consumption. The subjects who consume suffer, and therefore their behavior is interpreted as deviant or abnormal. The knowledge invoked to validate this conception is quite limited, summing up the ideas developed by a handful of eminent psychologists who have tried to establish the bases of this type of behavior. Regarding the production of knowledge, since it is a focus on the subjects, it is mainly focused on the description of cases, with few or no attempts at generalization. Community conceptions, which construct the problem in terms of the social or socio-environmental dimensions that explain the tendency to addiction, and which make up a "socially problematic subject".13,14

Unlike the previous ones, he conceives the problem in terms of a dysfunctional society, a product of which the subject who consumes is a manifestation of a social symptom. The biological materiality of the brain, the functioning of the psychic apparatus and the interpretation of the different types of substances go to a secondary plane. The intervention is thought in terms of "social re-education", that is, teaching the individual social capacities through which he can channel his vital energy without resorting to the use of substances. In this way, consumption is a deviant behavior, but it is not a disease in the classical sense of the term. It is for these two reasons that the different therapeutic activities of this type of conception do not relate to the classical core of medical therapies, but rather respond to the format of workshops for the acquisition of social skills (work, education, art, etc.), accompanied by a group of psychological and psychoanalytic therapies, group and individual. This conception resorts to diverse knowledge without a clear structuring among them. Thus, they are influenced by dynamic psychology, social psychology, community psychiatric perspectives at the same time as psychoanalysis, all with strong ideological and / or religious components. The previous reasons explain the low professionalization of these therapies. As for the production knowledge, there is a wide production in the description of different therapeutic strategies within this diffuse framework, without a clear structuring.

Public problem/knowledge problem

The word addiction admits a variety of definitions that have the common characteristic of considering it a problematic behavior or, to be more precise, deviant. However, to consider addiction as a problem is to assume that a behavior, a current phenomenon -the consumption of certain substances-, has certain social characteristics that make it such. But the phenomena do not have social characteristics these are assigned to it through various definition processes. In doing so, they become a social issue. Therefore, any phenomenon becomes a social problem when it is subjected to a process by which members of groups or societies define it as such.15–18

At the same time, social problems are often public problems. A public problem is any activity that the social subjects that, either by the very magnitude of the action, by the number of subjects involved or by the treatment that the media made, reaches the public sphere and is collectively constructed as such.19 For a social problem to become a public problem, it must also be a source of controversy in the public arena.19 And as is clear from the above, disputes are promoted by different ways of conceiving and intervening on a problem. The fact that we openly acknowledge that substance addiction is a public problem indicates that there is a social concern about the problem as it has been constructed and presented in the public sphere and that, in addition, there are struggles to define the problem of one or another way that is expressed in that area. This social concern is manifested in the establishment of public policies to deal with the problem, in the emergence of institutions, in the implementation of treatments, in the coverage of the problem by the media, in the establishment of legislative debates, and in the demand for solutions by society, among other manifestations. However, this situation is neither permanent nor natural. The public problem has its genesis, its development and, most likely, its end.

In this work we assume that the emergence of a problem of these characteristics, contingent decisions about how addiction is treated, what types of medical treatments should be implemented, where and by whom, are decisions that result from the interaction between different social actors that mobilize institutional mechanisms and knowledge that shape the interests of the parties involved and public opinion. Public policies regarding drug treatment are based on a series of abstractions that select some characteristics of reality. Among these characteristics, we find a quantitative construction -that is, the number of addicts that the State knows and recognizes through different statistics-, the way of conceiving addiction, associated to scientific knowledge or not, that will influence the specific devices of treatment and the adoption of regulatory frameworks.

According to Gusfield,19 it is possible to differentiate two dimensions of a public problem: the cultural dimension that expresses the symbolic level in which the problem is represented, and the dimension of social organization, which considers the patterns of activities through which the phenomenon considered (the public problem) is systematized in data and theories.19 But there is another aspect of the public problem of addictions that needs to be considered. The fact that it has been defined, at least in theory, as a "health problem" implies that the biomedical field should be especially involved in definitions, disputes and modes of resolution. In the same way as what happens with the descriptions of the construction of other public health problems - Chagas disease,20 alcoholism,17,19 Viagra,21,22 AIDS,22 to name but a few - there is a strong influence of biomedical knowledge on the way in which public intervention is thought and the strategies that are imagined and implemented for your solution. In the case of substance addiction this relationship is, as we shall see, more complex. What is the production of medical knowledge around this problem? What impact does it have on the resolution of the public problem?

Medicalization

Defining a problem as a disease is a more complex process than it superficially seems. There are different theoretical positions about what we call "disease". Is the disease an objective reality - viruses, parasites, etc. - is it a subjective suffering of individuals or is it a social construction? Some theoretical positions consider that a disease only exists when a specific condition is defined in this way by culture.19 What we are interested in is not a particular definition, but the concrete mechanism by which a definition manages to impose itself on others and manifests itself in concrete treatment strategies.

The medicalization of addictive behavior is twofold. On the one hand, generalized human behavior - the consumption of certain substances - has been pointed out as a medical problem. The addiction can be interpreted as a modification caused by the pharmacological medical intervention. The abusive uses of certain substances are rooted in the use of opium as medicine during the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.23 But on the other hand, addiction has been medicalized in the sense of trying to intervene pharmacologically in its treatment. There is a double play of substances: Those that were originally introduced and then banned or rejected by the Hegemonic Medical Model (opium, cocaine, heroin), later they try to eradicate using new substances (methadone, bupropion, etc.). One of the authors who has dedicated himself to study the influence of what we know with the name of scientific medicine in the structuring of modern medicine is Eduardo Menéndez24. This author raises the concept of Hegemonic Medical Model to interpret the totality of medical practices. According to Menéndez,24 the Hegemonic Medical Model [MMH] refers to:

"The set of practices, knowledge and theories generated by the development of what is known as scientific medicine. This model has been left as subalterns to the set of practices, knowledge and ideologies that dominated social groups and was identified as the only way to address the disease, legitimated by both scientific criteria, and by States.24 The hegemony of this model, according to Menéndez,24 is based on the type of relationship it maintains with other health care and prevention models and practices that exist in society. Mainly with what the author calls the Subordinate Alternative Model [MAS] and the Self-Support Model [MAA].

The MMH presents a series of structural features, among which, the dominant feature is biologism or the concentration of medical practice in what has been called biomedicine. Biomedicine includes the knowledge of biology, which gives the model the guarantee of scientificity and a specific differentiation with respect to other models and other medical or health care practices, prioritizing the type of knowledge that the MMH uses. The construction of hegemony by the MMH points to the ideological and legal exclusion of other care possibilities. However, the MMH plays an important role in the implementation of other non-hegemonic practices. For example, self-medication, the consumption of drugs (or drugs) without medical prescription. Self-medication is one of the aspects of self-care practices that the MMH combats not perceiving itself as responsible for this type of practice. Where, if it is not from MMH itself, does society learn how, when and in what quantity medicines should be used, a practice for which it is then condemned? Despite this, the MAA is strongly questioned by the MMH, without being directly responsible for the issue. This fundamental characteristic of MMH is crucial, we believe, to interpret, not only the addictive phenomenon but the totality of drug use. In general terms, the type of link that individuals and societies establish with drugs is ambiguous since its conception. Self-care, expressed through self-medication, learned by the patients of the doctors and also exercised by the latter on their own bodies (who diagnoses a doctor?), Was no less in the process of historical expansion of the patterns of consumption of opium, cocaine and other medications that caused accustoming.

Where does MMH's ability to impose its hegemony come from? Scientific medicine is based on the development of a particular type of knowledge that privileged physical-mathematical science, scientific knowledge and the experimental model. However, the values that have been added to this type of knowledge, and in which a large part of their legitimacy capacity is based, are not intrinsic. Since it was defined in the early 1970s, medicalization has varied in conceptualization, magnitude and scope, since medicine itself has broadened its "field" of action.17 As they have already.

According to many authors, the history of medicalization itself has shown that there is no "necessary" relationship between biomedicine and the consumption of psychoactive substances.25 It is also clear to observe how the pharmaceutical industry has been a promoter, producer and then opponent of most of the substances considered "drugs". The history of medicalization has shown this process in opium, morphine, cocaine, heroin, methadone, benzodiazepines, psychotropics, etc.17,23,26,27 In this way, any social, historical or political process that can intervene in the generation, development, dissemination or even cure of the pathology in question is denied. This ubiquity of the suffering in the biological body is important, since it allows for its abstraction and, later, its objectification in order to be able to perform the necessary extrapolations in animals, as we will see when we approach the chapter on biomedical research. Conrad has indicated three levels in which the medicalization of a condition can occur. The conceptual, institutional and interactional level.28 These three levels imply the growing involvement of medical professionals in different institutional frameworks that aim, all of them, to monopolize health care strategies.

The conceptual level refers to the field in which the problems are defined in medical terms. This happens at the level of basic research in biomedical sciences and at the level of pharmaceutical companies that are not only looking for new products for health problems, but are constantly trying to expand the markets for existing products by "inventing" new ailments.27,29 The Institutional level refers to the political intervention that medical professionals can have, either directly, or as consultants of third parties that occupy decision places. These professionals work to impose their own conceptions of health-disease-care processes using, generally, a scientific, biological rhetoric and based on criteria of therapeutic success measured from medicine itself, ignoring the broader sociocultural contexts.

While in the first two levels, according to Conrad, medical treatments are not necessary (since the existence of a treatment is not necessary to intervene conceptually or institutionally), at the interactional level, the axis is placed in the doctor-patient relationship and the medicalization at that level. The interesting thing about these concepts developed by Conrad is that they can be interpreted as a process (Figure 1). Although the process is not continuous or linear, it provides tools to qualitatively evaluate the influence of medicine, the degree of progress of medicalization on a particular behavior.

The local construction of addiction as a knowledge problem

The criminalizing conception

Estimating the consumption of illicit substances is very complex. There are not yet truly integrated international systems of statistics on consumption and production, although much progress has been made in their implementation over the last two decades.30 To estimate the consumption, three methods are used and the crossing of the data thrown by each one of them. The first consists of evaluating the cultivated area with each of the plant species. This method is very useful for the plantations of coca bushes and opium poppy plants, but it is not very useful for cannabis plantations, since they can be done in much more variable conditions. The second method consists in evaluating the quantities of drugs and unprocessed products that were confiscated by the existing control mechanisms and other police and customs operations. By means of these figures extrapolations can be made to the total quantities of substances circulating, entering or leaving a particular territory. Finally, in many countries, and more and more, studies are being carried out on the population's consumption. Surveys in general, school, university, police data, hospital statistics, studies in different labor populations and even data from insurers, contribute to shaping this universe.30‒33

In general terms, it can be said that, compared to the previous decades, the world consumption of opiates, cocaine and cannabis has stabilized in the world, while the consumption of amphetamine-type stimulants has increased, as has designer drugs and the use of prescription drugs for non-medicinal uses.34,35

The preparation of data on consumption is the responsibility of two international bodies that are responsible for the control of narcotic drugs and psychotropic drugs. The Commission on Narcotic Drugs [EC] and the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) of the United Nations Organization. These bodies, in accordance with the provisions of Article 5 of the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs of 1961, keep track of the consumption, production and trafficking of substances under control, with the cooperation of the World Health Organization [WHO], which acts as a consultative body. The EC is a subsidiary body of the Economic and Social Council [ECOSOC], which is composed of the Member States of the United Nations. It is the central regulatory body of the United Nations system to deal with all issues related to drugs.

INCB is responsible for monitoring the implementation of international drug control treaties. The Board was established in 1968 through the Single Convention of 1961 on Narcotic Drugs. It is she who determines the deficiencies of the national and international control systems and helps correct those situations. The INCB analyzes the information provided by governments, the different organs of the United Nations, the specialized agencies and other competent international organizations. Annually, and since 1994, the INCB has published a report to ECOSOC. The report offers an analysis of the situation of the fight against drugs in the world. This report is supplemented by various technical reports on narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances that provide data on the production, manufacture, trade, licit consumption, and (much) lesser extent, the treatment situation and the prevention of the use of these drugs throughout the world. World.30,36 In turn, the UNODC published in 1997, in 2000, and thereafter, on a yearly basis, a World Report on Drugs. The international data given below was obtained from these sources and helps us to understand the magnitude of the phenomenon of drug use in the world, and the place occupied by Argentina in that context.

Consumption in Argentina

In Argentina, the Argentine Drug Observatory belonging to SEDRONAR carries statistics at the national level and is the agency in charge of providing data to international organizations on everything related to drugs. In 2007, the Observatory presented a study in which the national situation of substance abuse was evaluated,37 where the following results were presented: (Table 1) (Table 2).

On the other hand, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, UNODC, in its 2010 World Report, presented the following data on consumption in Argentina. The same report indicates data of annual prevalence in the population between 15 to 64 years of 2.6% for cocaine consumption, 7.2% for cannabis use, 0.6% for amphetamine consumption, 0 , 5% for ecstasy and 0.16% for opiates. The sum of these consumptions gives us an annual prevalence of illicit substance use (including amphetamines) of 11.06%. These data clearly indicate that the panorama in Argentina is currently dominated by marijuana and cocaine, which, taken together, account for almost 95% of consumption. We must not forget that these data are not informing us about the number "addicts".

The first local attempts to produce and systematize information on the control of illegal drugs came from the South American Agreement on Narcotics and Psychotropic Drugs (ASEP). Since 1979, the Party countries had to submit annual reports on the consumption and trafficking of controlled substances. During the 1970s, the only data that were available were those produced by CENARESO,38 which also did not develop any efficient or unified methodology, limited to reporting randomly selected information. political purposes rather than for statistical or health planning purposes, and some data from Borda Hospital.

The 1980s seem to be characterized by the emergence, driven by the ASEP and the 1971 Convention, of the first attempts to systematize drug control information. Consumption increases significantly with the consolidation of the Therapeutic Communities movement as a response from civil society to a growing problem that did not find a sensitive interlocutor in the State. Consumption continues to be dominated by marijuana, but the second place is divided between cocaine and psychotropic drugs which, since the latter are not under the same control structure, are often invisible to controls. Surge in this decade also, as a relevant social problem, intravenous drug use which, accompanied by the emergence of AIDS, and the characteristic ignorance of that early period of the epidemic, would have important consequences on the survival of addicts and in the conformation of the social representation of the same. The decade of 1980 is at the same time an "intermezzo" between two periods of greater controls, although the decade of 1990 would surpass by far the one of 1970 in this sense.39

In the 1990s, control mechanisms were deepened through the creation of SEDRONAR and an institutional space was consolidated through the centralize national information. The punitive measures are re-hardening and the control becomes more specific. The government of Carlos Menem, which lasted throughout the decade, adopted a policy of "zero tolerance". which raised the possession for personal consumption to the category of drug trafficking.40

In 1970 Maccagno mentioned 700 drug addicts, while in 2000 the UN indicates a prevalence of more than 2 million people. However, the addiction category represents, for Maccagno, those individuals interned or locked up in public institutions, while the UN points out those people who have consumed "at least once in the last year". The difference in the way in which the "addict" is characterized at each moment is not expressed here in the definition of the same, but in how a particular category is included or not in the numerical elaboration of the reality of consumption. Thus, the annual prevalence data, by which most of the current statistics are made up, actually serve exclusively to characterize people who do not consume drugs at all. All the rest, that is, those that consume at least once a year, become part of the same category, making the most relevant set of consumers invisible. This way in which the numerical elaboration is instrumentalized is closely related to the lack of a hegemonic definition of what it means to be an addict. When not having that definition, the only thing that can be known is that something is not an addict.

The above data indicate that, until the end of the 1990s, the consumption of drugs in Argentina was a problem from which, basically, everything was ignored. The number of consumers was unknown and there was much confusion regarding the type of substances that they consumed most frequently. There are, on the other hand, a series of studies that account for the consumption practices of certain groups of consumers, but these studies are qualitative and do not contribute much to assess the magnitude of the problem in terms of the public construction thereof.22,41‒43

The neurobiological conception

The knowledge developed in neurobiology of addictions has become hegemonic in many discourses and the definitions that have the brain as a protagonist have been consolidated in the international arena. The neurobiological perspective has provided convincing elements to deepen the medical interpretation of addictive behavior. In this sense, it favors the discourses of many civil society organizations that work towards the inclusion of this problem within a health perspective and not exclusively as an oversight. However, most of the organizations with international influence that intervene in the design of intervention policies and strategies regarding drugs and addictions, with the exception of the WHO, do not consider it that way. We have already pointed out that the INCB, the DEA, the NIDA and even large sectors of the WHO have increasingly adopted this perspective. The World Health Organization, although carrying the hegemonic discourse of the medical profession, and in this sense also an institution with biologizing tendencies, is less permeable to the controlling discourse and more sensitive to other perspectives that consider the social and other dimensions of being human. However, due to their internal discussions and the strength with which the biological perspective is presented in other areas, alternative perspectives have not been able to prevail.

This conception conceives the addictive phenomenon as a function of the decompensation caused by the ingestion of a certain substance in the "normal" functions of the brain and the ability of psychoactive drugs to generate lasting changes in the central nervous system, which oblige the individual to continue to consume. Here the variable of "deviant behavior" is introduced through what neurobiology considers to be the normal functioning of the brain defining, therefore, addiction as a biological disease. Although this view does not ignore the substances, it does place them in the background, focusing on the materiality of the brain as an object of study and the central axis of research strategies with a view to developing effective treatments against addiction. This way of conceiving the problem, invisibilizes most of the subjective and social conditioning that may be relevant in the study of the addictive phenomenon. Thus, there is almost no question about the reasons that lead a subject (or a society) to consume this type of substance, prior to the establishment of addiction.

On the other hand, most of the neurobiological research is not carried out on human brains, but is carried out in the brains of mice, mainly male mice, with the epistemological consequences and practices that this entails. The knowledge used in the consolidation of this theoretical view is nourished fundamentally by the most positive branch of biology, molecular and evolutionary biology and the physiology of the nervous system with a strong influence of the behavioral psychological currents that are manifested in the design of laboratory experiments. On the other hand, the function that can be assigned to the knowledge produced by this conception is not so clear, as there are no significant therapeutic results. However, the results of experiments in mice are used as a rhetorical tool to validate this vision in other areas.

Neurobiological research in Argentina

As a way to have an approach to institutions and people who perform basic research in addiction neurobiology in Argentina, we searched different databases: SCOPUS, JSTOR, Medline, IME (Spain), Redalyc, Scielo and CONICET using the words ADDICTION + NEUROBIOLOGY (or Addiction + neurobiology), both at the international level and at the local level, up to and including 2008. This information was then crossed with information obtained from specific interviews to corroborate and expand it. The works found refer to the authors and institutions listed in Table 3.

This panorama situates us basically in three institutions: the Pharmacology Department of the University of Córdoba, the Pharmacological Research Institute [ININFA], of the UBA and the Research Institute in Genetic Engineering and Molecular Biology [INGEBI].

Juan Carlos Molina is a Principal Investigator of CONICET, a psychologist and a Doctor of Psychology. He has specialized in experimental psychobiology in particular in the mechanisms of early prenatal and infant development in the presence of alcohol. Although their research considers addictive behavior, they are not focused on the development of therapeutic measures, but rather on understanding the consequences of alcohol consumption on early embryonic and early childhood development and its cognitive implications.

The ININFA has an exclusive line of research in Neurobiology of addiction that is directed by Dr. Graciela Balerio. Dr. Balerio is a pharmacist and started working in 1992 with Dr. Rubio, current director of ININFA, on the mechanism of action of an agonist drug to GABA-B receptors and its inhibitory effects on the regulation of analgesia, baclofén. Balerio finalized his PhD thesis on this topic in 1996, one of whose results was to find relationships between the GABAergic system and the opioid system.44 In 1998, he requested his first grant to young researchers from the UBA to work on the effects of morphine in these systems. Dr. Balerio gets in touch with a very important researcher in the field of studies neurobiological of addictions, Dr. Maldonado, with whom he would end up doing his postdoctoral thesis at the Pompeu Fabra University, in Barcelona.

According to Dr. Balerio, there were no researchers in Argentina working in this area under this perspective at that time and her training was very self-taught, until the year 2000, when she accessed Dr. Maldonado.45 Upon his return, in 2004, he had to completely recondition the workplace in the UBA, as he was not prepared to develop the techniques he had learned in Spain. In 2007 they establish a line of knock-out mice in GABA-B receptors and begin to work in nicotine, preparing various biotechnological techniques that would allow the genetic data obtained from these mice to be systematized.

Despite, however, this apparent marginality in the field, the research conducted by Dr. Balerio and her group play some role in shaping the problem in our country, as we have been discussing: in 2008, Dr. Balerio organized a doctorate course in the Faculty of Pharmacy and Biochemistry entitled "Neurobiological Bases of Addictions", aimed at a wider audience than the specialists in neurobiology. In that course there were also some invited professors: SEDRONAR staff and Dr. Gorlero, of the Convivir Foundation. When investigating the types of links that exist between Dr. Balerio, ININFA and these institutions, we have not been able to find, on Dr. Balerio's part, any formality or commitment beyond the inclusion of certain assistance perspectives in the subject of course. However, when doing the opposite task, that is, when consulting the institutions about the reasons why they are interested in participating in a course of these characteristics, we received a marked interest, both from the Convivir Foundation and from the representatives of SEDRONAR to endorse the perspective promoted by the course. Both institutions mean it in terms of "the most advanced knowledge" or "a new perspective with which we have a debt, in the sense that it has not yet been included in welfare terms". Regarding Dr. Rubinstein, despite being the molecular biologist who has the most publications in the area, his research cannot be included in the local production of neurobiological knowledge about addictions, since his name is mentioned through the obtaining of certain modified mice, which later would be very useful in the study of certain aspects of addictions, as he points out:

"I made the mice, and then since those receptors are supposedly involved in certain circuits and linked to certain pathologies, and addiction is one of them, there were many jobs that we did, especially in collaboration, where the laboratories that are experts in addictions were not we were the collaborators.46

These are the main lines of research into the addictive topic from a neurobiological perspective in Argentina. As we see, the role they play in the local development of basic knowledge is very poor, and practically none in the development of knowledge applied to specific therapies. Despite this scarce local production of neurobiological knowledge in addictions, it cannot be said that the neurobiological perspective has no weight in shaping the problem at the local level. What happens, in our opinion, is that this perspective is operating at the conceptual level as it has been described by Conrad and for this, the development of local knowledge is not required. The research carried out at NIDA or the Pompeu Fabra University is as valid (or more) than the research carried out here. These observations also show the absence of an effective use of the little knowledge that is produced and what is even more striking, of the knowledge that is obtained as a result of the training of professional researchers.

The psychoanalytic conception

TyA (drug addiction and alcoholism)

In Argentina, the dominant psychological current (although this is currently changing rapidly), is Lacanism. This institution undertakes, for the first time in the national psychoanalytic field (and would be a pioneer at the international level), a research organized around the addictive theme through the Toxicomania and Alcoholism Group, the TyA. The TyA is a research and training department of the Lacanian Orientation School. It proposes research and specialized training in the field of Freudian Lacanian orientation in the area of addictions. This group emerges as an effect of the conformation of the EOL but has its national background in the Vector of Alcoholism and Drug Addiction of the International Library of Psychoanalysis and in the Working Group on Drug Addiction of the Symposium of the Freudian Field.

Originally the group TyA was developed, in Argentina, in the Institute of the Freudian Field. Its beginnings date from the year 1988.47,48 In 1992, with the formation of the Lacanian Orientation School (EOL), the TyA group became part of it and, since then, the TyA conducts a weekly seminar in an uninterrupted manner where various topics of discussion are discussed. drug addiction and alcoholism questioned from Lacanian psychoanalysis. This seminar is open and free.

Additionally, this group holds monthly meetings of organization and coordination. In 1994, TyA began to collect its research, publications and activities in a periodical magazine, Pharmakón, which has been published since 1994 on a semi-annual basis. It is important to note that the TyA does not perform treatments or attention, it is a space for theoretical reflection and training in which psychoanalysts of this orientation can obtain therapeutic tools and share experiences to apply in their professional practice.

The group TyA does not believe in emptiness. On the contrary, he has his background in the group GRETA (Research and Study Group on Toxicomania and Alcoholism) that takes place in Paris, the group CEREDA, also from France that was in charge of Hugo Freda, the group MACERATA, in Macerata, Italy and the Fundanalítica Center Group, of Caracas, Venezuela, created in 1986.48 From 1992 to the present, TyA has been constituted as a space for reflection on the addictive problems in the psychoanalytic field. He has contributed to the training of professionals, has offered courses and conferences in public hospitals and universities and has established himself as a reference in the area of drug addiction in mental health congresses in Argentina.

Since the publication of Pharmakon, TyA has a formal space from which to disseminate its research, its discussions, its annual activities, and the activities of associated groups around the world that, in 1993, formed the "TyA Network". This network is made up of different groups of similar characteristics that carry out research, training and even treatment of addicts from the same perspective in different parts of the world. These groups were related in the successive international meetings of the Freudian Field, expressing the idea of the realization of a joint publication and the formation of a network that uses it as a formal way of communication in the VII International Encounter of the Freudian Field that took place in Caracas in 1992.

In 1992, when the first meetings of the TyA take place, among others are Rudy Bleger, Graciela Brodsky and José Luis González, important Argentine psychoanalysts and structuring people in the field of addictions. It is very difficult to quantify the specific influence of the activities of the TyA Group in Argentina, but both its formal members and the professionals who attend or have attended its seminars are scattered throughout the public health system of addiction care. Likewise, their trajectory in informal training activities and extension activities means that they are on the lips of all professionals in the area. On the other hand, there is no space for specialized psychoanalytic training in addictions that represents other therapeutic modalities, so that the Lacanian orientation has become hegemonic. As an indicator of the extent of the influence of TyA activities, we will point out some institutional insertions.

As we can see, the main public institutions for the treatment of addictions in Argentina are run by people who make up the TyA. This, together with the proper structure of the Freudian field of Lacanian orientation that was forming a very closed language and institutions with very clear initiation rites, fosters theoretical endogamy and the uniqueness of approaches.

The community conception

In 1973, Carlos Novelli became a pioneer in the attempt to develop treatment systems based on the therapeutic community in Argentina. This year the Andrés Program was founded, which was nothing more than the meeting of people with a common goal: to stop using drugs. It was what was known as the Community Farms, to which Novelli gave it a strong religious stamp. Carlos Novelli was born in 1953, at 18 he was a young addict on a trip to the United States. There he meets a person who introduces him into a church where he manages to recover from his addiction. It is not clear if this institution was Daytop or another institution with similar characteristics.49,50 The case is that Novelli manages to recover from his addiction and with the strength of this experience returns to Buenos Aires and begins with the task of trying to recover his old friends and acquaintances of their respective addictions. He tells them about his experience in sporadic meetings and gathers a small group of collaborators, addicts, evangelists and addicts-evangelists, with whom he forms what Grimson,51 prefers to call "Units of survival".51

There they gave roof to those who wanted to recover from addiction. They received help from families and religious organizations. They produced salable objects and tried to subsist in this erratic and unorganized way. The treatments, if that name can be given to what was done there, consisted mainly in sustaining abstinence by voluntarily submitting to the rules of the community. In 1986, Carlos Novelli founded FONGA, the Federation of Non-Governmental Organizations of Argentina for the prevention and treatment of drug abuse, which received legal status in 1991. With the political renewal that implied the return of democracy in Argentina, many institutions began to change. The CONATON, Until that moment directed mainly by Cagliotti, begins to be restructured in what would be the CONCONAD. Wilbur Grimson requests a special commission, which was called the "Prevention Commission". In this Commission, Grimson begins with the task of including different organizations of civil society: The Andrés Program, the Parents Association for the Prevention of the Use of Narcotic Drugs (APPUE), the FAT and the CT Viaje de Vuelta, among others.52,53 The CONATON that worked in CENARESO was dissolved and in its place the CONCONAD-CONAD was created, as it was alternatively called. De Vedia, the third executive undersecretary of CONCONAD. (after Malamud Goti and Bertoncello), he defended the participation of civil society in the topic of addictions. De Vedia had been Assistant Secretary for Human Development, a Secretariat created in 1983 in the Ministry of Health. The Council of the minor depended on him and he gives his support to Grimson in the implementation of the Prevention Commission.51,52 These civil society organizations received the first subsidies granted by the State to work in some aspect related to the prevention and/or treatment of addictions.52

De Vedia was a personal friend of Giulio Adreotti, who had been Prime Minister of Italy and would occupy the presidency of the Council of Ministers between 1989 and 1991. Andreotti was an important representative of the Italian Christian Democracy that, during the 1980s, was very active in the area of addictions in the United Nations (and still is) in the wake of the heroin epidemic that was in that country. In the United Nations, Italy was represented by the CEIS, a civil and Catholic organization that, as we pointed out earlier, was gaining space until becoming in 1985 an official consultative body: De Vedia goes to see Alfonsin and says, I have a way, with the drug issue that interests you so much, I'm Andreotti's friend, as you know, and he told me that he can get me an agreement, and they they will finance from the United Nations.52

Andreotti and De Vedia, through the Italian Chancellery, propose an agreement between Argentina, the United Nations and Italy to hold a training course on addictions. The Italian government, through the CEIS and with funds from important firms such as FIAT, Olivetti, La Banca Nazionale del Laboro and the Vatican, which strongly supported the CEIS, allocated a lot of money to the Italian Foreign Ministry, which referred it to the corresponding body in United Nations. In turn, the Italian Foreign Ministry made an agreement with Argentina.54,55 to finance a training course dictated by specialists from the Uomo Project. Finally, much of the money went back to the origin from where it had started. That is, the Italian companies financed the CEIS who contributed the money indirectly to the United Nations. This body financed, finally, the activities of the CEIS in Argentina.

In 1987 Novelli traveled, as president of FONGA, along with Grimson and Silvia Alfonsin to the annual meeting of the INCB, the International Narcotics Board of the United Nations, which contacted the Uomo Project.50‒52 From there begins an important link. In the same year, project AD/ARG/87/525,56 was signed between the Argentine Government and UNFPA. The objective of this project is the creation of a center that responds to the local demand for professional training in the area of addiction treatment.54 At that time, the national body in charge of the prevention and treatment of addictions was CONAD, which takes over the management of the future Center (which would never be carried out). With funds from UNFID, then, 30 scholarships are granted (27 were used) to send operators Argentine sociotherapeutics in Italy, to the CEIS facilities, where the operators would complete a 2-month training period there in the CEIS Therapeutic Communities, and return to the country under the idea of forming the aforementioned center.49‒51,54 The members of the Argentine group that travels to Italy were, mainly, former addicts in advanced stages of their treatment and a few professionals (psychologists and sociologists). CENARESO sent 3 people. Among them, the graduate in psychology Adriana Agrelo who upon her return resigned her position and became part of the first professionals who worked in a TC, joining Esperanza Youth Center.57 This group formed what today they call "the first generation of Therapeutic Operators".

Then, between 1988 and 1990, Italian professionals from CEIS, together with the operators trained in this experience, gave an annual course in Buenos Aires: In this period, the communities were still managed mainly by former addicts and religious leaders. The training at the CEIS in Italy and later in Argentina was the first approach to a professionalized staff. Neither doctors nor psychologists (except for exceptions) and much less psychiatrists, participated in the therapeutic programs designed in these institutions.

In 1987, the Andrés program had about 120 residents.49 Also by this time the proposals are extended. Appears next to the Andrés Program, the Viaje de Vuelta Program, directed by Jorge Castro, the Esperanza Youth Center, founded by Carlos Sánchez, an evangelist pastor. This center was then led by Rubén González,49 who had gone through the Andrés program and had traveled to Italy to train. Rubén González,49 worked as a teacher in the course that was dictated in Buenos Aires. The course given by the CEIS was gradually replacing its teachers by the locally trained operators. It was carried out for three years and trained 189 operators. With the change of government, in 1990 it was discontinued.

In 1994, the "pastor" Carlos Novelli dies and Grimson takes over the management of FONGA. From there, it begins to promote the professionalization of operators and the recruitment for FONGA of more civil society institutions that deal with the treatment of addicts: During the management of Novelli in FONGA, I served as Secretary of organization, recruiting new members, promoting training in prevention and treatment and organizing annual participatory seminars for member institutions and special guests, among them: Pedro Cahn, Dr. Cattani , Eduardo Amadeo, Father Gabriel Mejia of the Latin American Federation [of Therapeutic Communities], Andrés Thomson (Kellogg Foundation), Maria Marta Herz (Social Sector Forum). The culminating point was when, in 1994, the Rector of UNQUI, Engineer Julio Villar, invited us to lead the Prevention of Additions Area. But that's another story.51 Between 1997 and 2004, at the National University of Quilmes, under the direction of Wilbur Ricardo Grimson, a course of "Socio-Therapeutic Operator" was given. On November 20, 1997, the National University of Quilmes decided to create the Area of Drug Dependency through resolution 839/97.58,59

In this way, the UNQ became the first National University to resume what was proposed by the Ministerial Resolutions that had been coming into being since the beginning of the 1990s when treatments for addicts began to be regulated in law 23,737, a long process that would not be reflected until the second third of the decade with the implementation of the aforementioned joint resolutions.60,61

The Drug Addiction Area belonged to the University Extension Area. To implement the Course, the University signed an agreement with FONGA,62 which at that time was directed by Grimson. Through this agreement, the University pledged to pay FONGA the sum of 55,000 pesos per year in nine monthly installments, in addition to providing classrooms and brochures. On the other hand, an agreement was established between the UNQ, FONGA and the Secretariat of Prevention and Assistance to Addictions of the Province of Buenos Aires, directed at that time by Dr. Juan Yaría.63 In this resolution, the Provincial Secretariat undertakes to provide financial support to the UNQ, but no amount is set.62,64 These agreements were annual and were renewed periodically. In 2000, the agreement with FONGA was replaced by an agreement with Fundación Proyecto de Vida, also directed by Grimson.65 The courses lasted two years with a total of 144 classes. 496 theoretical hours, corresponding to eight subjects and 64 hours corresponding to eight workshops with an additional 254 hours for internships.

In addition to the management of Grimson, the course was coordinated by Silvia Vulijscher (social psychologist), Susana Scardera (social psychologist and group coordinator of the Life Project Foundation), Alberto Rey (Socio-therapeutic Operator Project Uomo-FNUFID, 1990) and Sandra Contrera. On the other hand, it had stable speakers of the first national level in the area of addictions. Among them were Lic. Graciela Touzé (Civil Association Intercambios), Lic. Alberto Calabrese (FAT) and María Elena Goti, among others.

From this description, it is clear the role played by Wilbur Ricardo Grimson in the promotion of, on the one hand, the general movement of Therapeutic Communities in Argentina, both from official areas and from their participation in organizations of the third sector. On the other hand, it was a strong promoter of the professionalization of the TC, a fact that is clearly manifested in its commitment to the training of operators, both in its role played in the consolidation of the Argentina/Italy agreement, and in the implementation of the course in Quilmes.

As Wilbur Grimson pointed out when he assumed the leadership of SEDRONAR in a journalistic interview:

Q: Is the health system in a position to recover an addict?

WRG: The public, no; the private one, yes. The mixture between the two gives us a possibility to carry out actions through the therapeutic communities. Ten years ago we had 10 institutions, now we have 60. Although they have felt in their own flesh the reduction of the budget item, which was 450 thousand pesos to 200 thousand and there are some serious commitments.

As he had been doing from his experience at Esteves Hospital, then at FONGA and at UNQ, Grimson would continue to support the CT movement from SEDRONAR. After the experience in Quilmes, the courses of socio-therapeutic operators diversified. The CTs proliferated and became a work outlet especially for recovered addicts (as it was before, but in this time, early 2000, multiplied): FONGA began to give its own course of operators; In 2006, the Civil Association Centro Psicosocial Argentino launched its own course, led by Daniel González; The Assistance Network of Buenos Aires has a sociotherapeutic operator career in drug addiction, as well as the University of Salvador where there is a center for the prevention of addictions directed by Juan Alberto Yaría.63

The construction of addiction as a public problem

CENARESO

In 1973, the National Center for Social Reeducation [CENARESO] was created, the first State institution dedicated exclusively to the treatment of addicts. This institutional creation is the result of an international movement promoted by the United Nations Organization from where it began to contemplate the need to establish assistance centers and research in the field of treatment for addictions. On the other, it is a response to what we might call the "first wave" of welfare demands that arose at that time in national public hospitals. But fundamentally, the creation of CENARESO is the product of the action of Carlos Cagliotti.

Towards the end of the 1960s and the beginning of the 1970s, a battle between two different ways of understanding Mental Health was taking place in the country. The old Psychiatry, solidly established in the psychiatric hospital and in the university chairs, proclaiming as its own the new economic place provided by the law of Social Works, and the new psychiatry, closely linked to psychology and psychoanalysis, which had won field in general hospitals, and in different non-medical psychoanalytic institutions that were developed in this era and that had a more social and democratic conception of care.

In December 1971, the VII Meeting of Ministers of Public Health of the Countries of the Plata Basin,33,66 was held in Buenos Aires. One of the objectives of this meeting was to discuss the modifications introduced in the recently signed Psychotropic Substances Convention with a view to updating the regulation of the region in the control of international traffic in narcotic drugs. In this Convention, as we have already mentioned, the international mechanisms for the control of narcotics were strengthened, but also for the first time in the field of international regulations with this decision, the need for medical attention of users of psychotropic substances was included. In this meeting, it was pointed out the need for each Latin American country to organize institutional structures that address the different aspects of the problem, in which the assistance and preventive aspects were included.

CENARESO,38 As a delegate from the Argentine Republic, Dr. Carlos Cagliotti, a psychiatrist who worked at that time in the INSM, attended that meeting. After the VII Meeting, according to versions collected orally and due to internal conflicts in the INSM, which most likely have to do with the management of Cagliotti as auditor of the Hospital Estéves in previous years, Cagliotti is assigned the task of " design "an assistance institution for drug addicts. Cagliotti was a person of action. Entrusting this activity, under the express instruction to do so "from the desk", had a specific purpose: to respond to the growing international demands. There is no data that suggests the idea that CENARESO was created to respond to the incipient demand for care that was being generated in national hospitals and to which no one knew exactly how to deal with it. Some sources point out that either this was a "punishment" perhaps because of the excessive public exposure that the events of the Esteves had or was a way of removing Cagliotti, for a time, from the public scene. The concrete thing is that it is not clear that there has been a real political intention to create a welfare center for drug addicts of particular characteristics.

The design of this center represented a challenge for Cagliotti, which was taken personally. For this, Cagliotti begins a process of research, institutional relations and international trips in order to study the state of the art of attention to drug addicts in the world. Cagliotti travels to different countries collecting local experiences in this type of treatment. In the United States he visits the Rehabilitation Centers of the State Department in the cities of New York, Lexington and Miami. Towards the end of the 1960s, in the United States, most of the states became involved in the creation of facilities to intern addicts.67

Cagliotti's visits to Lexington and New York are contemporary with these institutional creations and the first organic policies in the United States that sought to treat addicts (in line with what was proposed internationally).23 Given that there are data that confirm certain institutional links between CENARESO, NIDA and other North American institutes, the official activities that Cagliotti was to carry out in the United States should have put him in contact with these experiences.49,52 In 1972 Cagliotti travels to Geneva as Argentine Plenipotentiary delegate to the Conference where the amendment of the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs of 1961 was signed. He was also an advisor to the Argentine delegation at the South American Plenipotentiary Conference on Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropics held in Buenos Aires and where the South American Agreement on Narcotics and Psychotropic Drugs (ASEP) was signed on April 27, 1973, which would be validated later in our country by law 21,422, in 1976. From that moment, Cagliotti would be Executive Secretary of the Permanent Secretariat of ASEP, installing its offices in CENARESO and administering an annual budget of $100,000.

He was a delegate in the Latin American Seminar on Prevention and Education of Drug Abuse held in Washington and the Latin American Seminar on National Programs of Research in Drug Dependence, held in Mexico. He was also Argentine representative in the binational Argentine-American Commission for the fight against Narcotic Drugs, in 1972.

CONATON

As a result of the aforementioned activities, Cagliotti promoted the creation of a Commission that would take charge of these issues and that would work as a way to respond to their professional interests and to the commitments assumed internationally. As a result of these efforts, the National Commission of Drug Addiction and Narcotics (CONATON) was created by decree 452 of 1972, within the Ministry of Social Welfare. This commission was chaired by the Minister of Social Welfare, who received technical assistance from an executive secretary: Carlos Cagliotti. CONATON was, therefore, an independent and inter-ministerial body. Cagliotti managed with this maneuver to evade the disputes that he had in the field of mental health while he managed to "escalate" politically, capturing the attention of other government areas on the problem in which he had been, in a very short time, an expert. His expertise, on the other hand, did not come from spaces of academic or assistance training. It came on the contrary of institutional relationships and, above all, trips abroad and participation in international forums. From his position in the CONATON Cagliotti suggests the creation of a specialized center that, as we pointed out, he was already designing for some time. This is how CONATON created CENARESO in 1973 through law 20332.

CENARESO

CENARESO is created as a decentralized entity of the Ministry of Social Welfare of the Nation, belonging to the Secretariat of Promotion and Social Assistance. Here it should be noted that CENARESO is not created within the Ministry of Public Health existing in that Ministry. This institutional dependence would mark its trajectory and signify the conflicts that broke out in the 1980s. Unlike most of the care mechanisms that existed in public hospitals or the Therapeutic Communities where the care structures were armed with a strongly practical imprint, driven generally by the demand for care, which led to the organization of specific areas that they decided, with time, in departments with a greater or lesser degree of institutionalization, CENARESO is an institution that was born in a desk. Cagliotti wrote the project (although Alberto Calabrese insists on pointing out that the institutional design is a copy of a Hospital in Lexington,52 he carried out the managements to obtain a property and the necessary funds for its conditioning. Cagliotti was director of CENARESO between 1973 and 1987, at the same time that he worked, during most of this period, as executive secretary of CONATON and executive secretary of ASEP.

Since its creation, the Center offers free assistance to drug addicts. In addition, local and remote prevention tasks are carried out, informing and educating about the risks of drugs and specialized training and training for professionals, technicians and university students. Its objectives are, among others, to provide comprehensive responses, addressing all aspects of the addictive phenomenon in relation to the preventive, assistance and re-socialization segments.

CENARESO has gone through different institutional ways of addressing the problem of the addict. These can be organized in three periods, according to the assistance criteria that were implemented and that differ in central points between one stage and the next. The first period begins with its creation and extends until 1986, under the direction of Cagliotti, and which we call "classic period". It is the period that responds most faithfully to its original conception. In the second period, the Center is intervened during the government of Raúl Alfonsín and adopts a modality more akin to the movement of Therapeutic Communities. We call it "community period." Finally, a third period, which began in 1992, but which was consolidated in 1994, when José Luís González, the current Assistant Director of the Center assumes that position, and who is characterized by a strong psychoanalytic imprint of Lacanian orientation. We call it "Lacanian period." In 1985, shortly before his intervention, CENARESO was transferred to the Ministry of Health of the Ministry of Health and Social Action. This is the first time, since its creation, that the Center has become the direct jurisdiction of Health. Currently, it functions as a decentralized agency of the Ministry of Health.

SEDRONAR

In 1983, when he assumed the constitutional government of Raúl Alfonsin, CONATON was disarmed and the National Commission for the Control of Drug Trafficking and Drug Abuse (CONCONAD or CONAD) was created by decree 1383/85. This commission was chaired by the President of the Republic, had a vice president, the first of which was Dr. Jaime Malamud Goti. As additions were Silvia Alfonsín and Alberto Calabrese Jr., who has collaborated with Alfredo Carballeda and Graciela Touzé, former colleagues of the FAT.

In February 1982, the President of the United States, Ronald Reagan, officially declared the "war on drugs".23,68 A strategy of his government to face the problem that considered that a large part of the high consumption of drugs in that country was a consequence of external factors. It made the producer countries publicly responsible, originating the stereotype of the foreign drug trafficker.69 Sometimes later, his wife, Nancy Reagan, launched her "Just say NO" campaign. This campaign was launched on April 24, 1985 at a conference to which the First Ladies of America were invited to personally deal with the problem of drug addiction, presiding over the fight against the drug problem in each of their countries. As Raúl Alfonsin's wife was very ill, Silvia Alfonsín, her sister, occupied that place. Upon his return from this meeting, Silvia Alfonsín, along with Anne Morel de Caputo, the wife of the Argentine Foreign Minister, constitute the Convivir Foundation, which would also play an important role in the consolidation of civil society organizations in the country. Through this Foundation, CONCONAD and CONICET the first investigations were carried out in the area of addictions.70,71

CONCONAD/CONAD provided, to the extent possible, support to civil society organizations, and maintained a distance from the interventionist policies of the United States. In 1989, when the handover of the presidential command took place, an event occurred that caught the attention of those who worked in the area. For years, the national parliament did not agree on the contents of a law regulating everything related to drugs. The controls and judicial decisions of this period show a more open interpretation of the existing laws with respect to the previous periods, which meant that a new law would follow this direction. However, in September of 1989, less than two months after assuming the presidential control, the current law 23,737 was sanctioned in which the possession of drugs was penalized.

This law was formed on a bill that had been introduced by the deputy Lorenzo Cortese in 1985 (Cortese would be Secretary of SEDRONAR in 2000).72 The new government dissolved the CONCONAD and created, through decree 671/89, the current Secretariat of Programming for the Prevention of Drug Addiction and the fight against Drug Trafficking, SEDRONAR, whose first Secretary was Alberto Lestelle.

SEDRONAR is the state agency responsible for coordinating national policies to combat drugs (drug trafficking, chemical precursors, legal trade in narcotics) and against addictions (prevention and assistance). For the first time, control, prevention and assistance actions were unified in our country, a fact that, according to some authors, hindered the good performance of all of them.

However, SEDRONAR has imposed a mission impossible to be fulfilled by law: that of dealing with money laundering, drug trafficking, control of income and production of drugs, educational training, prevention and treatment of addictions. On the one hand, it must coordinate the actions of the Police, the Customs and the Gendarmerie, and also establish banking policies to control money laundering. It is obvious that the sum of the fields does not benefit the development of the policies, generating a well-known phenomenon in several countries: the development of traffic control actions ends up absorbing more resources than the reduction of demand, financially, politically and in the difficulty of concentrating on different problems".73 The assistance of the consumers in SEDRONAR is coordinated through the Undersecretary of Planning, Prevention and Assistance, which is responsible for coordinating and implementing national plans and programs, taking into account the guidelines set forth in the "Federal Plan for the Prevention of Drug Dependence and Control of Illicit Drug Trafficking ".

When it comes to providing treatments, SEDRONAR makes referrals. It has an admission system, where the drug user is interviewed and the need for treatment is defined. In this interview, it is established to which institution it will be derived, according, among other things, to the complexity of the case. SEDRONAR, as we have already mentioned, has a registry of Lending Institutions, which are those authorized to receive the hospitalization subsidies that are granted to patients. This registry consisted,74 of 112 institutions. Of these, 64 provide residential treatment.

For FONGA, the Federation of Non-Governmental Organizations of Argentina for the prevention and treatment of drug abuse, most of the institutions included in its registries belong to the modality of Therapeutic Community. FONGA has in its registries around 70 institutions that offer some type of treatment. Of these, at least 43, provide residential treatment and are considered in their vast majority, Therapeutic Communities. It is very difficult to estimate the number of institutions that, at present, work with the modality of Therapeutic Community in Argentina. This is due, fundamentally, to the difficulty of defining what a therapeutic Community.

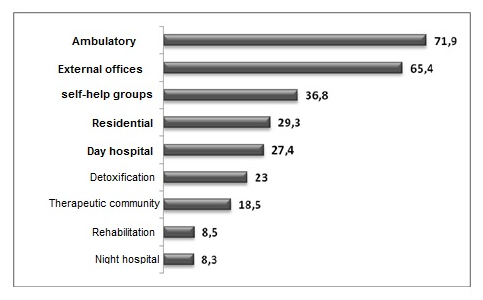

In a study conducted by SEDRONAR itself, which attempts to characterize all the healthcare institutions in Argentina, regardless of whether they are providers or not, the following figures are presented (Figure 2).

In this graph, obviously, each center responds to more than one category (% does not add up to 100). However, the TCs have their own category, although they could be subsumed within the type of treatment called residential. According to those responsible for the preparation of the survey, this is so due to the number of institutions that call themselves in this way and do not correspond exclusively to the category "Residential" (responsible for the survey, personal communication). It is complex to unravel, based on the methodology used in this survey, the actual number of TCs. The total number of centers in this study is 592. Therefore, 109 centers belong to the TC category (18.5%) and 173 provide residential services (29.3%). Therefore, out of 173 residential centers, the majority (63%) are TCs. Many institutions will have resolved to respond in one category or another, since the definitions are lax. This decision may respond to the stigmatization that TCs have received in certain areas (due to their religious or authoritarian structure) or to the idealization that they have also received in others. Depending on the context, the fact that an institution is considered a TC or can not result in benefits or harm to it. However, comparing these data with those of the FONGA registries and the Registry of Institutions that provide SEDRONAR, it is evident that the number is closer to 173 than to 109. In any case, with more than 110 centers, the modality CT becomes the most numerous residential treatment modality in the country.

On the other hand, when the study carried out by SEDRONAR analyzes the type of financing received by the TCs, it is pointed out that they receive mainly private or mixed financing -public and private-. What the study does not say, is that the totality of the CTs surveyed (108) are the same that benefit from the subsidies granted by the State. Nothing prevents these institutions, in addition to receiving patients subsidized by the state, having their own patients (and thus become "mixed" institutions), so we believe that the conclusions of this study do not reflect reality.75,76 The TCs represent the specific devices for the treatment of addictions that are more financed by the State at present, because not only the number that, as we just showed, is more than relevant, is of interest. The amounts involved in this treatment modality, being residential, are much higher than those of other non-residential modalities.

Figure 2 Distribution of treatment centers according to the treatment modality they offer in 2009 (% of total centers)..

Main Drug (%) |

|||||||

Year |

Cannabis |

Opiates |

Cocain |

Amphetamines |

Ecstasy |

Inhalants |

Treatments |

2006/2007 |

40,2 |

0,5 |

51,2 |

0,5 |

0,4 |

7,3 |

2434 |

Table 1 Main drug (%)

Annual Prevalence 15-64 Years Old (%) |

|||

Mens |

Women |

All |

|

Opiates |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Cannabis |

8,8 |

5,4 |

6,8 |

Cocain |

2,1 |

2,1 |

2,5 |

Ecstasy |

0,5 |

0,4 |

0,4 |

Any illicit drug |

8,41 |

6,25 |

7,3 |

Table 2 Annual Prevalence 15-64 Years Old (%)

Researcher |

Institution |

Articles |

Molina Juan Carlos |

Inst. Inv. Médicas Mercedes y Martin Ferreyra |

12 |

Rubinstein Marcelo |

ININFA/INGEBI |

7 |

Cancela Liliana |

Inst. Inv. Médicas Mercedes y Martin Ferreyra |

6 |

Molina, VA |

Inst. Inv. Médicas Mercedes y Martin Ferreyra |

6 |

Almirón RS |

Inst. Inv. Médicas Mercedes y Martin Ferreyra |

2 |

Balerio Graciela |

ININFA |

1 |

Diaz Valeria |

ININFA |

1 |

Bonacita |

ININFA |

1 |

Table 3 The works found refer to the authors and institutions listed

Thus, as we have been able to reveal through various interviews and the analysis of the treatments for addicts existing in Argentina, the absence of medical professionals is revealed as a characteristic and widespread feature, although not universal. The origin of the treatments in Argentina, at least of the treatments that later resulted in the establishment of a public care system, was strongly related to religious movements, self-help groups of the Alcoholics Anonymous type and certain therapeutic strategies taken, almost without the intervention of medical professionals, of the new social psychiatry developed since the 1950s and its community derivations.13,51,63,71,78-89 These treatments have been professionalized over time, but even today, the care structure within this system continues to be mixed.74 On the other hand, most addicts are treated in institutions that are physically separated from the central health institutions (hospitals).

This could be taken as an indicator that indicates that, although the addictive behavior is medicalized, this occurs mainly at the conceptual levels, which allow rhetorically to influence reality and institutional levels, that is, those from which the strategies are designed. intervention policies (medical or not), but not at the interactional level, the doctor-patient relationship is not verified. For example, it is clear that the main care strategy of SEDRONAR is the use of the therapeutic capabilities of third sector organizations. The registry of SEDRONAR provider institutions and the registration of institutions affiliated with FONGA are highly coincident. These characteristics could be an indicator of the "state" of the medicalization of the addictive behavior in Argentina, but also, of the strategy deployed by the MMH to hegemonize its view regarding the problem.

As we pointed out, the criminalizing conception has become the hegemonic view on drug addiction. This concept has spread to the whole world and to our country, mainly through the signature of the different international conventions that, since the beginning of the 20th century, have been established in terms of international control of substances. This conceptualization had a huge impact on the rest of the ways of conceiving the problem. Both in the biologizing conception and in the subjective conceptions it had the double effect of limiting the possibilities of research on the one hand, and hindering access to medical treatments on the other. This provoked a therapeutic vacuum that was filled by community strategies that were not submitted, at least for a time, to the same type of regulations and forms of social control as the more structured medical systems. This mechanism is observed in a paradigmatic way through the process of reception of the Therapeutic Communities and in the "compartmentalization" that has received the medical treatment of addiction, both in institutional terms and in specifically spatial terms: addicts are not treated in the same physical spaces as other diseases. This does not respond to problems of infrastructure or therapeutic devices, but to the way in which addicts are conceived and treated by a society (by sectors of society) at a given historical moment, and by a particular medical system. If we observe the problem of addiction to substances at the interactional level, we observe that, in our country, the Therapeutic Communities conform, in terms of assistance institutions, the privileged way that the State has chosen, since the beginning of the 2000s, to give answer to the problem. However, they are not fully validated by the medical system, as can be seen in the regulatory attempts that have been made, in which the medical aspects do not achieve adequate structuring. Additionally, the physical separation to which we mentioned, causes the health effectors working in these institutions to be disconnected from the broader scope of general health, provoking this but even today, the care structure within this system continues being mixed.74 On the other hand, most addicts are treated in institutions that are physically separated from the central health institutions (hospitals).