MOJ

eISSN: 2573-2935

Case Report Volume 3 Issue 3

Department of Psychiatry and Neurobehavioral Sciences, University of Virginia School of Medicine, USA

Correspondence: J Kim Penberthy, Department of Psychiatry and Neurobehavioral Sciences, P.O Box 800623, University of Virginia School of Medicine and Health System, Charlottesville, VA 22908, USA

Received: November 28, 2016 | Published: April 17, 2017

Citation: Penberthy JK, Khanna S, Lynch M, et al. Effective treatment for co-occurring alcohol use disorder and persistent depression: a case report. MOJ Addict Med Ther. 2017;3(3):66-69. DOI: 10.15406/mojamt.2017.03.00035

Alcohol use disorders and persistent depression are highly prevalent, frequently co-occurring disorders, both of which pose significant burdens on the healthcare system in the United States. Treating both disorders concomitantly may significantly decrease health care demands, psychosocial disruption, and mortality rates, but effective treatment of this patient population is challenging and complex. Comorbid depression is associated with poorer prognosis during alcoholism treatment, and depressed mood may be an important trigger for relapse. Cognitive Behavioral Analysis System of Psychotherapy (CBASP) has empirical support in reducing depressive symptoms by increasing the patient’s emotional safety, decreasing their interpersonal avoidance, and improving their perceived functionality. The CBASP approach involves a unique case conceptualization and learning acquisition paradigm which emphasizes social learning and appears ideal for treating co-occurring depression and addiction. CBASP has only recently been employed for use in patients with comorbid depression and alcohol use disorders. We present a case of a 52-years-old male with diagnosed major depressive disorder, alcohol use disorder, and anxiety and describe implementation of CBASP with the goal of reducing both depressive symptoms and alcohol consumption. Outcomes and implications of this approach for treating comorbid depression and alcohol use disorder are presented.

Keywords: Depression; Alcohol use disorders; Cognitive behavioral analysis system of Psychotherapy; Comorbidities

CBASP: Cognitive Behavioral Analysis System of Psychotherapy; HAM-D: Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; CIWA: Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol; SA: Situational Analysis; SDU: Standard Drinking Units; CBT: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; MI: Motivational Interviewing; CSQ: Coping Survey Questionnaire; IMI-C: Impact Message Inventory Circumplex

Alcohol use disorder is frequently comorbid with other psychiatric disorders such as major depression, and professionals working with these patients are facing a unique challenge.1 The estimated cost of excessive drinking in 2010 was $249.0 billion, which equates to $2.05 per drink or $807 per person.2 The prevalence rate for major depression rose from 13.8 million to 15.4 million adults between 2005 and 2010, and this increased the cost by 21.5 % from $173.2 billion to $210.5 billion in 2010.3 As a result of the deleterious psychological impact on the individual and the economic burden on society, there is a growing need to develop and evaluate effective treatments for these significant and prevalent disorders.

There are currently multiple empirically supported behavioral treatments for depression and alcoholism as individual disorders. However, there have been few well-specified, empirically supported behavioral therapies with an integrated approach to treating symptoms of both disorders.4-6 The most commonly evaluated types of behavioral therapies for co-occurring disorders include motivational interviewing (MI), cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and contingency management (CM); 4 research supports that an integrated therapy possessing components of MI, CBT, and CM would be most ideal to target co occurring depression and alcoholism.4-6 The lack of successful treatment options for chronically depressed alcohol dependent individuals may be due in part to the complex characteristics these individuals possess that make their treatment more challenging.7-10 Comorbid depression is associated with poorer prognosis during and after alcoholism treatment and depressed mood may be an important trigger of alcoholic relapse.7,11 Interpersonal avoidance behaviors are salient variables in individuals diagnosed with both alcoholism and depression. These patients typically report a high rate of adverse early home environments, a lifelong history of intrapersonal and interpersonal failure, an earlier onset of depression and alcohol use disorders, more comorbidity, a more severe course of illness, and they demonstrate interpersonal avoidance and detachment.8,12,13 Early abuse/trauma history impairs development of adequate interpersonal coping skills, resulting in depression, social isolation, or withdrawal.14 In addition, real-world and prolonged environmental stressors usually accompany these individuals’ presenting complaints. They are often skeptical or ambivalent about change, and the processes of change are often slow, irregular, and inconsistent. In fact, a pattern of success followed by a setback is common and periodic plateaus in progress occur. Significant personality issues, ranging from extreme passivity and avoidance to full blown dependent personality disorder, may be more likely in this population. These individuals typically live in chaotic physical and interpersonal environments, and are frequently surrounded by significant others who have been lied to or stolen from and who do not trust the patient.

CBASP is particularly proficient for use with the early onset of variety of unipolar mood disorders. Its etiological premise is that chronic depression arises as a result of a developmental history characterized by significant interpersonal trauma (e.g., physical/sexual abuse) or a low grade, but continuous stream of psychological insults (e.g., punishment/rejection of some form), which both lead to a preoperational form of thinking about one’s social world. This derailment is particularly characterized by a lack of causal awareness and egocentrism in the depressive patient. CBASP helps by creating an awareness of the impact of interpersonal behaviors as they occur in a therapeutic setting. This is done by aiding the patient in discriminating their experiences with the therapist from those experiences with harmful significant others from their past, to create a sense of felt interpersonal safety that can then be generalized outside of the therapy setting.15 Situational Analysis (SA), a major component of CBASP, is as an interpersonal problem solving tool which helps the patient actively re-experience an interpersonal encounter and safely learn social emotional interpersonal problem solving skills.15 These exercises help patients form causal connections between their mood symptoms and drinking behaviors which ultimately help in undoing these patterns.

In summary, CBASP is an intensive psychotherapy that focuses on addressing interpersonal avoidance and teaches coping skills by promoting felt emotional safety with the therapist which can then transfer to trusted others in the social environment. The patient will therefore gain the ability to recognize the interpersonal consequences of his/her behavior and will be enabled to do the work of change. CBASP has demonstrated effectiveness in treating chronic depression,16-18 and is also well suited for individuals who have extensive avoidance learning, high rates of early trauma, repeated interpersonal failures, and use alcohol to cope by “escaping,” “avoiding,” or “numbing.” CBASP is, therefore, ideal for treating this depressed population who also suffers from alcohol use disorders.

In light of the evidence suggesting CBASP as a promising psychotherapeutic model, a case study examining the use of 20 weeks of modified CBASP for co-occurring chronic depression and alcohol dependence was conducted at the University of Virginia School of Medicine in the Department of Psychiatry and Neurobehavioral Sciences in Charlottesville, Virginia. CBASP was minimally modified from the original format,19 and manualized for standardization and replicability. The initial phases mirrored traditional CBASP as it is used for persistently depressed individuals with additional assessments of the patient’s state of change and motivation levels for both depressive symptoms and alcohol use. The case conceptualization completed in the initial phase included a Significant Other History (SOH) of the patient to evaluate the learning impact of those individuals upon the patient, and assessment of the patient’s interpersonal style through the Impact Message Inventory Circumplex (IMI-C).

During the middle phase of treatment, the patient analyzes specific interpersonal situations using a social problem solving exercise called the Coping Survey Questionnaire (CSQ) to set realistic and attainable goals and explore what interpretations, beliefs, and behaviors help facilitate achievement of such goals. This is done by reviewing the CSQ and remediating it to help set realistic goals and achieve them. After remediation, alcohol reduction coping skills are identified and taught in the same manner that traditional CBT is conducted. Alcohol consumption goals are set in addition to depressive symptoms and quality of life/level of functioning goals for treatment. A harm reduction approach, similar to that utilized in motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioral therapy for alcohol dependence, is used to address alcohol consumption. Thus, patients do not need to be abstinent when in treatment and do not necessarily have to set abstinence as their goal, although it is preferred. The overall approach to symptom change is compatible with the CBASP essence of treatment, which allows the patient to establish how the therapy session will proceed and enables the patient to do the work of change.

The patient, Jon (fictitious name), is a 52-year-olddivorced, white male who has a past medical history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obstructive sleep apnea, and current major depressive disorder, moderate, as well as alcohol use disorder. He has had one prior psychiatric hospitalization after a suicide attempt via drug overdose. His current psychiatric medications include clonazepam 1 mg twice daily, aripripazole 5 mg daily, and desvenlafaxine 100 mg daily. On presentation, he reported that he consumes 47.5 standard drinking units (SDU) per week (a combination of beer and vodka) and started drinking at age 13. He also reported an extensive history of illicit drug use, further noting how his substance use helped him deal with negative emotions and interpersonal problems. Jon is no longer using illicit drugs, but has not been able to stop drinking. Jon’s stages of change data indicated that he was planning to reduce his current alcohol use and depressive symptoms, and appeared to be in the preparation stage of change for both. Initially his Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D)score was 16, which indicates mild-moderate depression,20 and Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol (CIWA)score was 2, indicating mild withdrawal symptoms.21 Jon’s goals for treatment were to reduce drinking and to better manage his mood so that he no longer uses alcohol to cope with his emotions.

Jon completed a SOH, IMI-C, and a timeline regarding onset of depression and alcohol and other substance use, which was used to inform his case conceptualization. Jon’s alcohol consumption was assessed using the Timeline Follow-back Method (TLFB), a psychometrically sound drinking assessment tool that is able to capture un patterned and sporadic heavy drinking days.22,23 Based on the SOH, Jon reported psychological and physical abuse at the hands of his father, and expressed that he learned as a child that it was not acceptable to express negative affect and that doing so would lead to rejection or harm from others. His scores on the interpersonal circumplex at the start of treatment indicated that he was typically submissive and hostile-submissive interpersonally and lacked ability to exert assertive behaviors.

He was also not perceived as friendly. Jon’s onset of depression occurred early in life, presumably in tandem with trauma from his father. He developed an alcohol use disorder as a teenager by his report to “escape the hell of his life,” as a maladaptive coping strategy in response to depressive symptoms as well as to reduce anxiety and fear regarding expressing negative effect. This fear of interpersonal rejection and lack of felt emotional safety was addressed in treatment by using the SOH and Interpersonal Discrimination Exercise (IDE). This exercise helped the patient discriminate between the past experiences which shaped the negative learning and present day experiences, where this learning may no longer apply. Despite the patient’s initial difficulty discriminating between feedback from the therapist and feedback from significant others when he expressed negative effect, he reported an increased sense of self-confidence to assert himself in a safe way with the therapist and others around him. Additionally, Jon and his therapist reviewed situations via the CSQ where he increasingly was able to set realistic and attainable interpersonal behavioral goals and achieve them. He was increasingly able to problem solve without drinking. He was able to thus gain perceived functionality and a sense of control over his interpersonal domain. He practiced and increasingly demonstrated the following coping skills: talking to self about coping with cravings, replacing alcohol use with more adaptive behaviors, setting realistic and attainable goals, demonstrating appropriately assertive interpersonal behaviors.

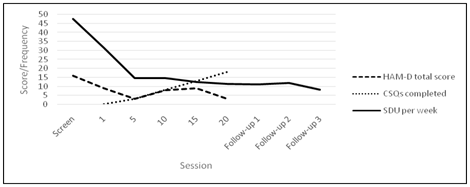

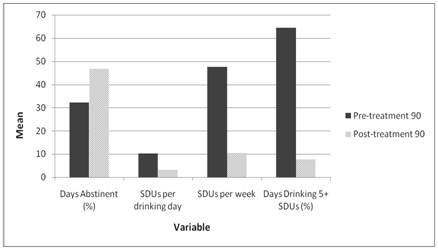

Over the course of treatment, assessment of Jon’s interpersonal style changed and on his final session he was less submissive, less hostile, and was assessed as slightly more friendly compared to his initial assessment (Figure 1). At screening, Jon was averaging 47.5 SDU per week, and had a HAM-D score of 16. In his final session, he was drinking less than 10 drinks per week with a CIWA score of 0, and his score on the HAM-D was 3, which indicated mild depression, which was much reduced from his initial score (Figure 2). A comparison between Jon’s drinking patterns 90 days pre-treatment and 90 days post treatment show profound improvements in both drinking frequency and magnitude (Figure 3). Furthermore, SDU consumption was maintained and revealed a decreasing trend from the final session to follow-up 3, four months after the final session (Figure 2).

This case demonstrates the effectiveness of CBASP in a patient with moderate depression and alcohol use disorder. During therapy, the patient was able to learn that his behavior had certain interpersonal consequences, and that he was able to attain desired outcomes by expressing his needs. This further aided him in connecting with his social environment, and helped him solve interpersonal problems in order to achieve realistic and attainable goals. By targeting these skills, the patient acquired “perceived functionality,” the awareness and capability to manage interpersonal consequences,24 which the patient utilized to reach their drinking goals. The patient’s skill modifications were effective in decreasing drinking consumption throughout treatment, and these changes were maintained at follow-up 3, indicating that the therapy’s effectiveness was maintained even four months following treatment.

There is growing interest in the co-occurrence of mood disorders and substance use disorder due to widespread prevalence, socioeconomic and healthcare burden. According to the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, nearly 41% of individuals who were getting treatment for an alcohol use disorder also had at least one co-occurring independent mood disorder, and alcohol dependent patients were 3.7 times more likely to have major depression. 25Therefore, effective treatments are urgently needed to treat chronic depression and alcohol use disorders concurrently, and CBASP is a “third wave” psychotherapy, which may be employed as an adjunct to medications. CBASP is designed for people who may have traumatic developmental histories, lack of motivation to change, poor awareness of their interpersonal interactions and problem solving skills.24 It is well tolerated by patients, safe to administer and is particularly beneficial for chronically depressed, alcohol dependent populations with high rates of “avoidance” learning.24 CBASP is unique in its ability to target and personalize to interpersonal issues and skill deficits, especially in patients who use alcohol to “escape.”Patients with chronic depression are particularly challenging and CBASP was specifically designed to meet the clinical requirements of these patients.26 Patient problems are viewed from an “outside in” rather than “inside out” perspective with a focus on interpersonal problems.26 The CBASP model is based on two assumptions: 1)“the interpersonal Skinnerian avoidant lifestyle of early onset patients is maintained and fueled by Pavlov an fears of being hurt by others” and 2) the patient is perceptually disconnected from the interpersonal world of people which can be observed during therapy sessions.15

The role of a CBASP clinician is unique as these patients are extremely ego-centric and often challenging to work with. The clinician must facilitate perceived emotional safety in order to help these fear-avoidant patients, develop new patterns of interpersonal approaches, consisting of moving towards people rather than retreating away.27 Studies are needed to dismantle the various components of CBASP in order to explore the role of each component in impacting change. Further, we also recommend more studies exploring the role of CBASP in treating comorbid disorders such as chronic substance use and depression over time. CBASP is yet to be studied in large trials, however this case report demonstrates that it may be an effective new tool in reducing symptoms of persistent depression and drinking behavior.

We would like to thank Dr. Jim McCullough, Jr. who developed CBASP.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

©2017 Penberthy, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.