MOJ

eISSN: 2576-4519

Review Article Volume 7 Issue 1

Department of Mechanical and Biomedical Engineering, City University of Hong Kong, China

Correspondence: Kelvii Wei GUO, Department of Mechanical and Biomedical Engineering, City University of Hong Kong, 83 Tat Chee Avenue, Kowloon Tong, Kowloon, Hong Kong, China, Tel +852-34424621, Fax +852-3442 0235

Received: July 13, 2023 | Published: August 9, 2023

Citation: Kelvii WGUO. NiTi shape memory alloys surface treatment for biomedical applications. MOJ App Bio Biomech. 2023;7(1):149-153. DOI: 10.15406/mojabb.2023.07.00187

It is well known that unlike human bones, metallic implants do not have self-healing ability and debris resulting from fretting between human tissues and implants may cause injury to human body. As an ideal candidate, NiTi shape memory alloys (SMAs) have good wear resistance because of martensite variants as well as superelasticity. In the period of loading and unloading, martensite transformation/transition and reverse transformation/transition effectively eliminate the strain and block the dislocation sliding in materials. As a result, the wear and fretting of material can be obviously reduced.

Nowadays, the commonly used materials for surgical implantation are titanium alloys, stainless steels and Co-Cr alloys. However, their Young’s module varying from 100 to 200 GPa and the values are quite different from that of human bones (1-30 GPa) resulted in causing “stress shielding effects” to loosen human bones.

Therefore, ascribed to more attractive promising clinical requirements with minimum potential environmental and human health risks, the approaches related to NiTi SMAs surface treatment for biomedical applications are remarked for long term biomedical applications.

Keywords: NiTi shape memory alloys, surface treatment, biomedical, nano, implant, wear

The unique shape memory effect in an equiatomic TiNi alloy was discovered in 1963.1,2 However, the efforts to make it commercialization did not take place until a decade later largely because of intrinsic difficulties involving melting, processing, and machining of alloy. It is delightful that many of these technical problems have been solved since the 1990s, and nitinol is actively pursued as biomaterials in biomedical engineering due to their unique mechanical properties.3,4 The corrosion resistance and biocompatibility are also quite desirable compared to other conventional biomedical metals such as stainless steels, Co-Cr alloys, and titanium alloys (Figure 1).5–10

As for shape memory effect, the relevant discovery in general actually dated back to early 20th century when Swedish researcher Arne Olander first observed the property from Au-Cd alloys.11 The same effect was observed from Cu-Zn.12 However, intensive studies on shape memory effect began only after the discovery of nitinol. The shape memory effect is a unique property of shape memory materials and NiTi SMA has the ability to return to a predetermined shape by heating.

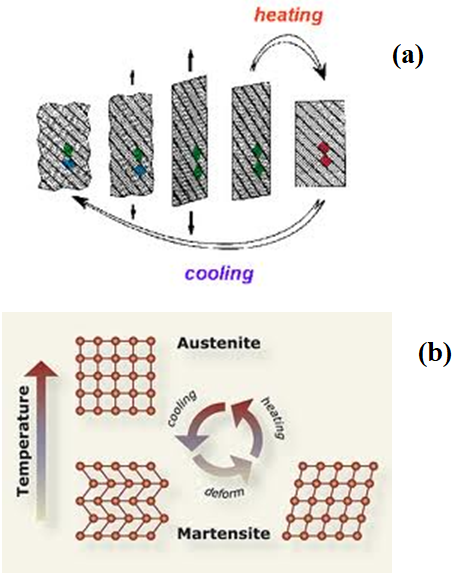

As shown in Figure 1a, when NiTi SMA is cold or below its transformation temperature, it has very low yield strength and can be deformed quite easily into a new shape which it will retain. However, when the alloy is heated above its transformation temperature, it undergoes a change in crystal structure which causes it to return to its original shape. Figure 1b depicts the crystal structure changes pertaining to shape memory effect. At original high temperature, NiTi SMA has an austenite phase (B2) with a cubic crystal structure. When it is cooled down, it transforms to a martensite phase (B19’) with a monoclinic crystal structure. At this moment, the martensite phase (B19’) is twinned. With subsequent deformation, detwinning occurs and the martensite phase is thus detwinned structure. The macroscopic shape of NiTi SMA is the one that deforms at a low temperature and subsequent heating converts the detwinned martensite to cubic austenite, at which the macroscopic shape is the original shape.

Figure 1 Schematic diagram of shape memory effect: (a) the variation of shape during the shape memory effect and (b) the variation of inside crystal structure during the shape memory effect.

Table 1 lists the mechanical properties of commonly used surgical materials. It shows that current implant materials such as stainless steels and Co-Cr alloys have Young’s module varying from 100 to 200 GPa and the values are quite different from that of human bones (1-30 GPa).13 An implant with a high Young’s module absorbs most of the loading causing “stress shielding effects” to loosen human bones. In contrast, the Young’s module of NiTi with the martensite phase is only about 26 GPa which is more similar to that of human bones.14

|

Materials |

Young’s module GPa |

Tensile Strength MPa |

Recoverable Strain % |

Elongation % |

Pressure resistance MPa |

Fatigue limit |

Hardness |

|

NiTi |

70~110 |

800~1500 |

2 |

- |

- |

100~800 |

65~68(HRA) |

|

NiTi (Nano) |

21~69 |

103~1100 |

8 |

>60 |

- |

50~300 |

- |

|

Annealed 316L |

176~196 |

552 |

0.8 |

50 |

550 |

343 |

170~200(HV) |

|

Ti6Al4V |

110 |

900 |

- |

12 |

900 |

170~240 |

- |

|

CoCr |

213~248 |

650~690 |

- |

8 |

- |

240~280 |

300(HV) |

|

Tooth enamel |

50 |

70 |

- |

0 |

265 |

- |

- |

|

Dentin |

14 |

40 |

- |

0 |

145 |

- |

- |

|

Cortical bone |

18 |

140 |

- |

1 |

130 |

- |

- |

Table 1 Mechanical property of biomedical materials

Surface modification of NiTi shape memory alloys

The bulk properties of biomaterials such as non-toxicity, corrosion resistance, degradability, modulus of elasticity, and fatigue strength have long been recognized to be highly relevant in terms of the selection of right biomaterials for a specific biomedical application. The events after implantation include interactions between the biological environment and artificial material surfaces, onset of biological reactions, as well as the particular response paths chosen by the body. The material surface plays an extremely important role in the response of the biological environment to artificial medical devices.

Titanium can be easily oxidized in the presence of oxygen. When samples are exposed to air, a thin oxide film forms on the surface. This native oxide layer can block the leaching of nickel ions from substrate to human body. However, the thickness of this layer is only about 3-7 nm.15 However, fretting may destroy thin oxide layer causing out-diffusion of nickel ions. Therefore, this native oxide layer is not adequate and some surface treatments must be conducted to improve the surface properties. Another important reason for conducting surface modification is that specific surface properties that are different from those in the bulk are often required.16 For example, in order to accomplish biological integration, it is necessary to have good bone formability. In blood-contacting devices such as artificial heart valves, blood compatibility is crucial. In other applications, good wear and corrosion resistance is also required.

Surface treatment is important in many bio-engineering products. They are typically small in size. Major dimensions are up to a few millimeters. Examples are dental blades and structures for implants, forceps and pincers for endoscopic procedures, and stents and scaffolds which go into vessels and parts of human body. Such products can benefit from surface treatment to improve mechanical properties near the surface.

Shot peening/Sand blasting

Engineering surfaces are often treated for the improvement of surface properties and removal of defects.17 It is well known that after the forming of engineering parts, surfaces are often subject to post-processing procedures to remove defects and to enhance surface properties. Sand blasting is done to remove machine marks and asperities from surfaces. Surfaces may also be blasted for texturization. Shot peening is considered a cold-working process. It is performed by throwing metallic shots on a metallic surface at high velocity. This helps to release residual tensile stress and introduce compressive stress near the surface, and to improve resistance to fatigue wear. Work was done to investigate the fatigue and corrosion behavior of stainless steel.18–20 Shot peening was applied to enhance the fatigue of aluminum alloy for aircraft application.21,22 It is used in various engineering components like leaf springs, gears and high strength fasteners. However, such methods to increase the strength and surface hardness may not be scaled down suitably for treating small structures or weak structures.

Laser cladding/Arc spraying/plasma spraying

Another approach of surface treatment is done by applying a hard or corrosion resistant surface layer on the part surface. A different metal is fused to a substrate through laser cladding. Examples include cladding on alloys of Ti, Al and Mg.23–28 Powder is either blown into the interaction zone or pre-deposited on the surface. Cladding should be done carefully to ensure high bonding strength with the least amount of dilution. Along the approach of forming a functional layer by melting of coating materials, other work includes arc spraying29–31 and plasma spraying.32–34 The surface of NiTi SMAs was also treated by laser melting and the corrosion resistance of NiTi SMAs in simulated body fluid (SBF) was improved. The treatment could effectively impede leaching of nickel ions into SBF solution. The drawbacks of such approaches are heat related processing which have the problem of heat affected zone (HAZ).35,36

Ion implantation

The third approach to surface treatment is through ion implantation. Ions bombard and penetrate a surface to change the lattice structure and thus the surface properties. Depth of penetration is in the micron level. The properties include hardness, resistance to wear and corrosion37 of metals and alloys were enhanced, and the properties of semi-conductors and of bio-materials38–42 were improved. The treatment depends on how the beam is produced and accelerated in a multi-step process.

Research has been done to modify the surface using N, O, and C implantation into NiTi SMAs to form TiN, TiO, and TiC films.43–47 The extensive studies reveal that all TiN, TiO and TiC films could effectively inhibit the release of nickel ions form NiTi substrate. In vitro biological studies show that the surface modified NiTi SMAs favors the proliferation of osteoblasts. But, ion implantation is expensive and its efficiency is slow.

Chemical treatment

Chemical treatment is another means to modify the surface properties of NiTi SMAs to improve the biomedical properties. Researchers processed Ti with HNO3 to form a passive TiO2 and a Ni depleted region on the surface. NaOH or KOH was also used to treat the surface to enhance the bioactivity. After that, H2O2 + NaOH treatment was developed to modify the surface of NiTi SMAs. The investigation shows that an in situ TiO2 layer grows after pre-treatment with H2O2. The subsequent NaOH treatment leads to the formation of a titanate/titania composite layer. The simulated body fluid (SBF) soaking test indicates that pre-treatment in H2O2 improves the bioactivity and the nucleation period of apatite in SBF is obviously shorted.48–52 Advanced oxidation was also developed to fabricate in situ TiO2 on the surface of NiTi SMAs. This technique employs •OH which possesses a higher oxidation potential than H2O2. Therefore, the oxidation efficiency is greatly improved and the results show that both corrosion resistance and blood compatibility are enhanced. The anodic oxidation was adopted to prepare a dense TiO2 layer with a thickness of 10 μm in methanol. This technique reduces the nickel concentration in the TiO2 layer on the surface of NiTi SMAs.53–57

Another chemical method, the sol-gel method, was taken to fabricate TiO2 and SiO2-TiO2 layers on NiTi surface and their results sho that the TiO2 and SiO2-TiO2 layers could improve the blood compatibility of NiTi SMAs.58–64

Generally, implants are chemically coated to promote cell growth on the surface.65–67 However, the adhesion strength is weak and coating material is easy to peel off under scratching. Alternate coating treatments like plasma spraying and laser cladding are not suitable due to uneven distribution of residual stress, and heat effects on the coating and on the substrate layers.

Detachment of the coating layer can initiate at crack sites of chemically coated surfaces (Figure 2). So, an effective method should be developed to enhance the adhesion between the functioned layer and the substrate by (i) re-distributing residue stress and materials near the surface, (ii) ‘hammering down’ layer materials slightly elevated near the crack (Figure 2a); and (iii) ‘hammering down’ the elevated pieces, and (iv) breaking loose those fragments which are severely separated from the substrate (Figure 2b). Table 2 lists the relevant applications of surface treated NiTi SMAs.

|

Applications |

Surface treatment |

|

Bone fixation |

Chemical treatment; Ion implantation; Sand blasting; Shot peening |

|

Dental implant |

Chemical treatment; Ion implantation; Arc spraying; Laser cladding; Plasma spraying |

|

Heart valve |

Ion implantation; Shot peening |

|

Heart assist device/ Pacemaker |

Ion implantation; Shot peening |

|

Stent/Scaffold |

Ion implantation; Shot peening |

|

Breast helper |

Chemical treatment; Ion implantation; Arc spraying; Laser cladding; Plasma spraying; Sand blasting; Shot peening |

|

Eye aider |

Chemical treatment; Ion implantation; Arc spraying; Laser cladding; Plasma spraying; Sand blasting; Shot peening |

|

Others (dental blades; forceps/pincers) |

Chemical treatment; Plasma spraying; Sand blasting; Shot peening |

Table 2 Applications of NiTi SMAs with various surface treatment methods

Although NiTi SMAs can be modified by various techniques to improve the specific surface properties and functions, not all the problems can be overcome and further surface modification is often needed. One of the problems is associated with Ni which is known to have some toxicity and cause allergic reactions in some people. The study shows that the amount of Ni released from commercial orthodontic wires varied in a wide range from 0.2 to 7 μg cm-2. It has also been reported that Ni release can increase significantly with time and the high concentration will be maintained up to a few months.

Another problem is the disruption of surface coatings due to the mechanical abrasion. Cyclic motions between implants and human tissues not only disrupt the protective surface coatings, but also generate wear debris, further increasing the risks of immunological response. The failure of biological coatings due to the long term corrosion, wear, and fretting is a serious concern and it has been reported that wear debris mainly causes the failure of joint replacements.

However, TiN or TiO film fabricated on NiTi alloys is usually less than 200 nm thick and any disruption of the film due to the mechanical abrasion can easily reduce its biocompatibility. Although a thicker titanium oxide layer can be produced on NiTi alloys by thermal oxidation, the phase transformation behavior is usually altered because it is sensitive to temperature. Hence, in order to obtain a high-quality biological coating on NiTi SMAs for long term biomedical application, the treatment temperature, bonding strength between the coating and substrate, and the thickness of the coatings should be considered.

Therefore, a not-expensive mechanical method for the surface treatment of small structures of bioengineering products, which is beneficial to the release of residual stress and increase of surface hardness, without damaging the form of the base structure, with capable texturizing surfaces for functional purposes, should be explored along with the eco-requirements.

None.

None.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

©2023 Kelvii. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.