Journal of

eISSN: 2379-6359

Research Article Volume 11 Issue 6

Menoufia University, Egypt

Correspondence: Faculty of Medicine, Menoufia University, 7 Shaaban Diab Street, Shebin Elkom, Menoufia, Egypt, Tel +2-01007106778

Received: September 25, 2019 | Published: November 10, 2019

Citation: Ezzat E. Thenew in management of recurrent laryngeal granuloma: long term follow-up. J Otolaryngol ENT Res. 2019;11(5):245-251.. DOI: 10.15406/joentr.2019.11.00443

Background/Aim: Vocal fold granuloma (VFG) is a nonspecific inflammatory process with no well-defined pathogenesis so its clinical and surgical treatment is not standardized. The aim of the study is to determine accurately the longest permissible period of conservative treatment of recurrent VFG, after which the decision of surgery must be made through long-term follow-up of cases with large recurrent posterior VFG, in addition to assessing the results of anew regimen in management of VFG.

Material and Methods: this study conducted on 42patients with large recurrent posterior VFG that were on conservative management as long as the granulomas regress in size with follow-up intervals of 3 months through videolaryngoscope (VLS). Those with resistance VFG were subjected to surgical excision with intra-lesional steroid injection in the pedicle.

Results: The most frequent related etiopathogenic factor was gastroesophageal reflux, followed by laryngeal intubation and idiopathic. Clinical management with proton pump inhibitor, systemic or local steroids and voice therapy in addition to behavior modification techniques were enough for remission on 80.95% of the patients. Surgical excision for granulomas was effective in 87.5% of the patients. Early recurrences were noticed in only one patient that proved to have a major gastroesophageal problem.

Conclusion: VFG well responds to conservative treatment with complete recovery of maximum period 24months even if it is large and recurrent. Managing recurrent or large posterior VFG needs interdisciplinary team that involves an otolaryngologist, phoniatrician, gastroenterologist, and gastrointestinal surgeon. Voice abuse alone couldn't evoke the condition. Steroids are as important as anti-reflux medication in treatment of VFG.

Keywords: vocal process granuloma, post-intubation, dysphonia, recurrent granuloma, videolaryngoscope

VPG, vocal process granuloma; VFG, vocal fold granuloma; LPR, laryngopharygeal reflux; GER, gastroesophageal reflux

Vocal process granuloma (VPG) is first described by Chevalier Jackson in 1928 as “contact ulcer of the larynx”. It is also known by many names including; contact granuloma, vocal fold granuloma (VFG), post-intubation granuloma, and arytenoid granuloma.1 Vocal fold granulomas (VFGs) are benign lesions occurring from irritation of laryngeal structures on the vocal process of the arytenoid cartilage. As the mucosal covering in this area is a thin layer of stratified squamous epithelium, it is susceptible to being crushed by any object inserted into the glottis (e.g., tracheal or nasogastric tubes) and the cartilage beneath it, leading to inflammation and benign granuloma development.2 Jackson and Jackson,3 suggested that superficial ulceration and focal granulation result from a “hammer and anvil” action between both vocal processes. The etiology of VFG is still undetermined and it is mainly attributed to various factors: gastroesophageal reflux (GER) or sometimes named laryngopharygeal reflux (LPR), endotracheal intubation, vocal abuse, habitual throat clearing, low-pitched voice, and psychosomatic disorders. Smoking, postnasal drip, and throat infections may also be causative agents4. The designation of “idiopathic” VFG is given as a diagnosis of exclusion which posits that another etiology may exist.1

Despite its name, it is not a true granulomatous process in a pathologic sense as much as it lacks aggregates of mononuclear and multinucleated histiocytes, rather, it is a reactive/reparative process, in which an intact or ulcerated squamous epithelium is underlaid by granulation tissue or fibrosis.5 These changes consistent with underlying perichondritis that have been demonstrated on computed tomography (CT) scan.6 VFG is infrequent pathological lesion but has received considerable attention in the researches, probably because of frustration encountered in its clinical management. It is an exasperating lesion that has high tendency to recur irrespective of treatment. The recurrence rate after surgical excision is notorious approaching 92%.4,7 Benjamin and Croxson,8 reported a total of 50 surgical procedures to remove granulomas from 16 patients with an average of more than three surgeries per patient. Al‐Dousary,9 reported recurrence in 47% of patients 2 to 4 months after surgery. Because surgery is so frequently ineffective, other treatments have been reported. Many different therapeutic approaches have been used, but none with uniform success. Often, a conservative combination of empiric medical and behavioral therapy is initially tried in the symptomatic patient including; voice rest, voice therapy, topical and systemic steroid, anti‐inflammatory, anti-allergy, antibiotic, anti-reflux medications, post-excision irradiation, and botulinum toxin A injection. Surgery (cold steel, laser ablation/photothermolysis, or cryotherapy) remains an option when conservative measures fail, if airway obstruction is present, or when the diagnosis is uncertain (i.e., ruling out malignancy). These procedures can be performed in the operating room or as an in‐office setting.10–12

This is a prospective study conducted on 42 patients with recurrent large posterior VFG either after complete course of conservative management (5 patients) or post-surgical excision (37patients), whatever the technique, in the period between March 2014 and June 2019. Large VFG referred to the one which had diameter of ≥6.5 mm or that represented at least 50% of length of the vocal fold.13 These patients attended the outpatient clinic of Menoufia University Hospital or Tawasol Private Center, which specializes in sound pathology, to perform the necessary videolaryngoscopic examination prior to surgery, for follow-up of the result of conservative treatment, or presented by themselves when the symptoms reappear after a period of first improvement. After recurrence of the lesion, the patients consented for applying this regimen of treatment after a detailed explanation of its steps. Patients with concomitant diagnosis or history of epithelial dysplasia or laryngeal carcinoma or those with VFG anywhere other than posterior glottis were excluded from the study.

Data concerning gender, age, patients' complaints and their durations, suspected main etiopathogenic factor, first treatment performed, laryngeal signs through videolaryngoscope (VLS), the duration of complete resolution of the lesion, and duration of post remission follow-up to detected recurrence were tabulated and analyzed. All patients underwent VLS before applying the treatment and after it with 3months interval even after complete remission. The decision of surgical interference was performed on stabilization of the VFG in size, shape, and color for 3 successive follow-ups (more than 6months). Post remission follow-up period ranged from 10 to 39 months, mean of 21.88±3.87months. The diagnosis of contact granuloma was established by office VLS. Diagnosis was usually made on the classic appearance and position of the lesion, taking in consideration that the condition was in recurrence.

Etiologic factors had been identified as; GER or LPR, post intubation, vocal misuse/abuse, and Idiopathic based on history and physical examination, history, and symptoms. Patients were questioned about history of recent endotracheal intubation, and symptoms of reflux including; heartburn, belching, sour taste in the mouth, and water brash. To identify vocal abuse, patients were asked about shouting, loud talking, frequent pain or loss of voice with prolonged speaking, and the need to speak often in a noisy environment. Idiopathic VFG was a diagnosis of exclusion. Conservative therapeutic regimen included; behavior/life style modification, voice therapy, and medical treatment. Behavior modification techniques involved both voice hygiene education (voice rest, plenty fluids, increase environmental humidity when possible, decrease time spent in dry or dusty environments, reduction of laryngeal muscle tension, and elimination of phonotrauma), and lifestyle modifications to reduce GER that included avoiding provocative dietary agents (coffee, soda, chocolate, acidic foods, fried foods, spicy foods, artificial colors, preservatives, etc), avoid exposure to pungent odors, stop smoking, reducing stress, restrict meals' quantities with frequent episodes, increasing the interval between dining and sleeping, and elevating the head of the patient's bed, wearing loose clothes all the day, and chewing gum continuously.

Voice therapy technique used flow phonation of 3 voiced fricatives (/z/, /ƺ/, and /v/), one nasal sound /m/, and 3 vowels (/ha/, /hu/, and /hi/). Subjects received a weekly session of 30mints for at least two months that practiced twice daily at home. Voice therapy sessions stopped once improvement of voice quality achieved or of maximum 4 months (16 sessions). Voice therapy applied even if no dysphonia was reported. All patients received medical therapy consisted of: daily use of proton pump inhibitor (PPI) ControlocTM 40mg (Pantoprazole) tablets twice daily one hour before meals and MosaprideTM 5mg (Mozabride Citrate) tablets 3 times daily one hour before meals. Systemic steroid (DexamethasoneTM 3-5mg per day divided into two doses during meals for 3weeks without withdrawal) followed by anti-allergic cover, Prednisolone (xiloneTM syrup 5 mm three times daily for 2weeks). No antibiotics or inhalation steroids used. Anti-reflux medications continued for 3months after complete remission.

Patients who showed resistance with no regression and stabilization of the VFG in shape, color, and size were subjected to surgical excision. VFG removed surgically with the patient under general anesthetic using micro suspension laryngoscopy with cold knife excision (MSL excision) and adjunctive intralesional injection of long acting steroid (DiprofosTM 2ml–Betamethasone– in 2patients and BetafosTM –Betamethasone– in 6cases). Those patients were admitted as day‐stay patients. Data was statistically analyzed using SPSS (statistical package for social science) program version 22 for windows; for all the analysis Chi square test was done for qualitative variable analysis and p-value < 0.05 was considered significant while < 0.001 was considered highly significant. Data were shown as mean, range or value in 95% confidence interval (95% CI), frequency and percent.

Forty two patients [34 (80.95%) were male, 8 (19.05%) were females] that were diagnosed as recurrent large VFG were studied. Forty one out of 42 subjects had unilateral VFG while only one female patient that had large bilateral idiopathic VPGs. Male patients had ages ranged from 35 to 55years with mean of 44.94±5.5years, while female patients had ages ranged from 30 to 44years with mean of 38.50±5.7years. The patients' complains were dysphonia, globus sensation, repeated throat clearing, chronic cough, odynophagia, and difficulty of breathing that were presented in the following percentages respectively; 66.7 %, 61.9%, 28.6%, 28.6%, 23.8%, and 9.5% with duration ranged from 14days to 15months, mean duration of 4.35±3.17 months whether this represented their onsets since the initial appearance which was not improved with the previous line of management or that appeared after a period of remission.

As regard the etiologic factors, referring to patients' history, symptoms, and laryngeal signs, 26(61.9%) of subjects diagnosed to have VFG due to GER with suggestive VLS findings (erythema and edema of arytenoid region, interarytenoids pakidermia, and subglottic edema) in addition to suggestive symptoms (globus sensation, dysphonia, chronic non-productive irritating cough, throat clearing, and odynophagia), 6 (14.3%) post intubation (the symptoms occurrence coincided with laryngeal intubation), 6 (14.3%) idiopathic (with exclusion of specific symptoms and signs), and 4 (9.5%) were vocal abuse/ misuse (with history of using very loud or inappropriate sound, or screaming). GER disease had been reported as the most common etiologic factor in male patients that was presented in 24 out of 34patients (70.6%) while post intubation was presented in 4 out of 8 female patients (50%) (Table 1).

|

Etiologic Factor |

Gender |

|

|

Male (n=34) N(%) |

Female (n=8) N(%) |

|

|

GER (n=26 ) Post intubation (n= 6) Vocal abuse/misuse (n=4 ) Idiopathic (n= 6) |

24 (70.6%) 2(5.9%) 4(11.8%) 4(11.8%) |

2(25%) 4(50%) 0(00.00%) 2(25%) |

Table 1 Etiologic factors related to the patients' gender

On identifying the relation between the patients' complaint and different etiologic factors, there was a statistical significant relation as regard odynophagia, and throat clearing with the etiopathogenic factors as odynophagia was the main complaint (66.7%) in post-intubation patients in the time it was presented only in 33.3% and 15. 4% in idiopathic and GER patients respectively, while both chronic cough and globus sensation were highly statistically related to GER patients (Table 2).

|

|

Etiology |

X2 |

P. value |

||||||||

|

GER |

Idiopathic |

Voice Abuse |

Post intubation |

||||||||

|

No |

% |

No |

% |

No |

% |

No |

% |

||||

|

Dysphonia |

Absent |

12 |

46.2% |

2 |

33.3% |

0 |

0.0% |

0 |

0.0% |

6.9 |

0.074 |

|

Present |

14 |

53.8% |

4 |

66.7% |

4 |

100.0% |

6 |

100.0% |

|||

|

Chronic cough |

Absent |

14 |

53.8% |

6 |

100.0% |

4 |

100.0% |

6 |

100.0% |

10.34 |

0.016* |

|

Present |

12 |

46.2% |

0 |

0.0% |

0 |

0.0% |

0 |

0.0% |

|||

|

Globus sensation |

Absent |

4 |

15.4% |

6 |

100.0% |

4 |

100.0% |

2 |

33.3% |

21.99 |

0.0001** |

|

Present |

22 |

84.6% |

0 |

0.0% |

0 |

0.0% |

4 |

66.7% |

|||

|

Odynophagia |

Absent |

22 |

84.6% |

4 |

66.7% |

4 |

100.0% |

2 |

33.3% |

8.64 |

0.034* |

|

Present |

4 |

15.4% |

2 |

33.3% |

0 |

0.0% |

4 |

66.7% |

|||

|

Throat clearing |

Absent |

22 |

84.6% |

0 |

0.0% |

2 |

50.0% |

6 |

100.0% |

20.51 |

0.0001** |

|

Present |

4 |

15.4% |

6 |

100.0% |

2 |

50.0% |

0 |

0.0% |

|||

|

Difficulty of breathing |

Absent |

22 |

84.6% |

6 |

100.0% |

4 |

100.0% |

6 |

100.0% |

2.72 |

0.437 |

|

Present |

4 |

15.4% |

0 |

0.0% |

0 |

0.0% |

0 |

0.0% |

|||

Table 2 Shows the distribution of laryngeal symptoms in relation to different etiologic factors.

*= significant correlation. **= highly significant correlation

As regard the distribution of VLS findings in relation to different etiologic factors, (Table 3) showed that posterior erythema and edema, and interarytenoids pakidermia were presented as the most common laryngeal findings in GER patients (80.8% and 76.9% respectively) with significant correlation when comparing their presence in other etiologies, while localized vocal fold submucosal hemorrhage was significantly related to patients with post-intubation VFG. Subglottic edema didn't show in statistical significant difference on relation to different etiologies (Table 3).

|

|

Etiology |

X2 |

P. value |

||||||||

|

GER |

Idiopathic |

Voice Abuse |

Post intubation |

||||||||

|

No |

% |

No |

% |

No |

% |

No |

% |

||||

|

Posterior erythema & edema |

Present |

21 |

80.8% |

2 |

33.3% |

1 |

25.0% |

4 |

66.7% |

8.45 |

0.038* |

|

Absent |

5 |

19.2% |

4 |

66.7% |

3 |

75.0% |

2 |

33.3% |

|||

|

Subglottic edema |

Present |

14 |

53.8% |

2 |

33.3% |

0 |

0.0% |

4 |

66.7% |

6.2 |

0.103 |

|

Absent |

12 |

46.2% |

4 |

66.7% |

4 |

100.0% |

2 |

33.3% |

|||

|

Interarytenoids Pakidermia |

Present |

20 |

76.9% |

2 |

33.3% |

1 |

25.0% |

2 |

33.3% |

8.66 |

0.034* |

|

Absent |

6 |

23.1% |

4 |

66.7% |

3 |

75.0% |

4 |

66.7% |

|||

|

Localized vocal fold hemorrhage |

Present |

2 |

7.7% |

2 |

33.3% |

0 |

0.0% |

3 |

50.0% |

8.3 |

0.04* |

|

Absent |

24 |

92.3% |

4 |

66.7% |

4 |

100.0% |

3 |

50.0% |

|||

Table 3 Shows the distribution of videolaryngoscopic findings in relation to different etiologic factors

*= significant correlation.

All patient received a common regimen; Behavior modification (voice hygiene and anti-GER measures), Dexamethasone 5mg/day for 3weeks, Prednisolone syrup 15 mm/day for the next 2 to 4weeks, PPI (ControlocTM 40 mg/day) and MosaprideTM 15mg/day for 3 months after complete remission (reported period from 6 to 37 months, of mean 16.14 ± 2.11 months), and voice therapy sessions (once weekly) ranged from 8-12 session with mean of 9.7±1.6 session.

Thirty four (80.95%) out of 42 patients (30 male and 4 females) exhibited complete remission after a period of conservative treatment ranged from 6 to 24months with mean 13.88±5.4 months. Patients who reported complete remission are followed up to the end of the study duration for purpose of recurrence detection. The follow-up period ranged from 10 to 39months with mean 21.88±3.87. Those who exhibited resistance with stabilization of the lesion in shape, color, and size [8 out of 42patients (19.05%)] were subjected to direct microlaryngoscopic surgical excision with intraoperative intralesional injection of long acting steroid and oral antibiotic for one week post-operative beside the common regimen. Those patients were followed up for a period ranged from 15 to 21months with mean 17.75±2.55. On follow-up, only one male patient with right posterior large VFG of GER etiology who was subjected to its surgical excision after a period of conservative treatment of 24 months and exhibited complete remission for 7months, showed recurrence of a moderate sized VFG on the same side. The patient was referred to a gastrointestinal surgeon, laparoscopic fundoplication was performed and follow-up was completed.

A regard the relation between the remission and different etiologic factors, (Table 4) showed that there was highly significant relation between the etiology and the rate of complete remission as VFG caused by GER had the greatest ability for complete resolving upon conservative management (92.31%), while post intubation granuloma had the least ability to resolve upon conservative management as all patients with post intubation granuloma involved in this study needed surgical interference.

|

Etiologic Factor |

Complete remission after conservative treatment |

X2 |

P.value |

|

|

Yes |

No |

|||

|

GER (n=26 ) Post intubation (n= 6) Vocal abuse/misuse (n=4 ) Idiopathic (n= 6) |

24 (92.31%) 0(00.00%) 4(100%) 6(100%) |

2 (7.69%) 6(100%) 0(00.00%) 0(00.00%) |

30.03 |

0.0001** |

Table 4 The relation between different etiologic factors and the rate of complete remission

**= highly significant correlation.

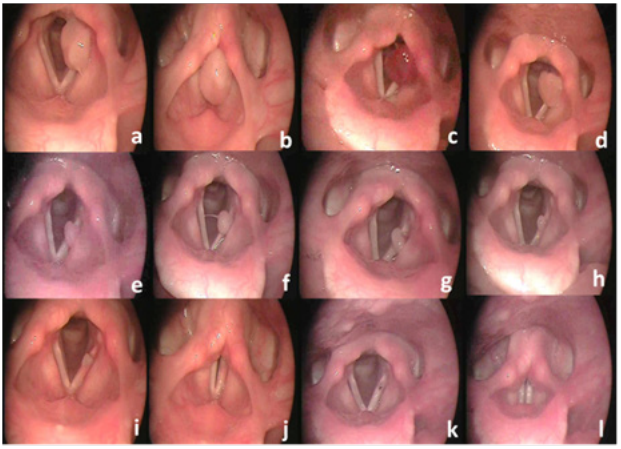

Case 1: A 42years old house wife female was referred to phoniatric clinic at our specialized private center with a 4-month history of voice change. Over this period, her voice had become increasingly worse. The patient had symptoms suggestive of gastroesophageal reflux (globus sensation, throat clearing and odynophagia). Examination of her glottis with a 90о rigid fibreoptic laryngoscope revealed a large posterior supraglottic granuloma of his left vocal fold 12.5mm in diameter (Figures 1A& 1B). After 2weeks the patient referred for post-operative assessment, as she subjected to surgical excision of the lesion that revealed nearly a same picture as that reported preoperatively. After 2months, the patient referred again for VLS examination after another operative session but this time with another same sized by severely congested hemorrhagic lesion at the same site (Figure 1C). At then, and after communicating with the responsible surgeon and taking his agreement for using the designed conservative regimen with the patient, the stages of treatment were presented to the patient who approved it. The patient had started behavior modification measures and medical treatment as soon and was arranged for voice therapy that lasts 2months (8 sessions). Figures 1F–1M showed VLS serial follow-ups of 3months intervals. The patient achieved complete remission after 21months and followed up after that for 26months without recurrence.

Figure 1 Rigid fibreoptic laryngoscopy showing large left vocal fold granuloma of gastroesophageal reflux etiology (preoperative). (A): respiration, (B): phonation. (C): assessment after surgical excision for the second time. Serial follow-ups. (D): after 3mons, (E): after 6mons, (F): after 9mons, (G): after 12mons, (H): after 15mons, (I): after 18mons respiration, (J): after 18mons phonation, (K): after 21mons respiration, (L):after 21mons phonation.

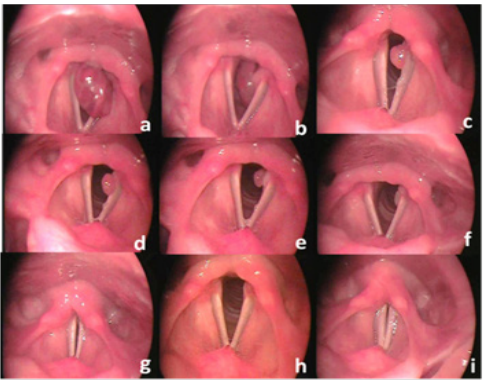

Case 2: A 30-years old female works as a tax officer that had attended to the phoniatirc unite Menoufia University Hospital with old history of change of voice character associated with difficulty of breathing on effort few days after a general anesthetic for a Caesarean section. She turned to an otolaryngologist who diagnosed her as having post intubation large left VFG and performed surgical excision. The patient did not experience any improvement after surgery. Upon VLS examination, a large sized recurrent VPG detected that was reddish in color, pedunculated with healthy intact mucosa and measuring nearly 2.3×1.7×1.5cm (Figures 2A&2B). After receiving the patient's consent to be involved in the study, conservative management started that lasts 9months with initial rapid regression in size through the first 3months (Figure 2C) but stabilization in shape, color, and size then developed running on 3 successive follow-ups (Figures 2D&2E). According to the current study the decision of surgery had been taken. The patient subjected to surgical excision with intra-operative intralesional long acting steroid (Betafos) injected in the base of the lesion. VLS performed one week post-operative that revealed mild to moderate tissue edema at the site of the lesion (Figures 2F&2G). Complete resolution had achieved 3months post-operative Figures 2H&2I and followed up after that for 17months without recurrence.

Figure 2 Rigid fibreoptic laryngoscopy showing recurrent post intubation large left vocal fold granuloma (postperative). (A): expiration, (B): inspiration. (C): assessment 3mons after starting conservative management. Serial follow-ups. (D): after 6mons, (E): after 9mons. one week post-surgical excision with intralesional steroid injection. (F): respiration, (G): phonation. 3mons post-surgical excision (H): respiration, (I): phonation.

Posterior vocal fold granuloma, or vocal process granuloma as described by many articles, is a haunting problem for the patient, speech language pathologist, and the otolaryngologist. The main etiology of VFGs remains undetermined but they are thought to be the end‐result of inflammatory processes promoted by chronic irritation of a damaged region of laryngeal mucosa. Initial laryngeal trauma may occur with mucosal injury from intubation, voice abuse/ misuse, or exposure to acid refluxed fluid. An inflammation is potentiated by repeated mechanical impact on voice abuse and chemical irritation due to gastroesophageal reflux, causing submucosal chronic inflammatory infiltration and arytenoid perichondritis, leading to granuloma formation.10 Laryngeal granuloma is reported in 22% of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) patients according to Koufman.14 The term vocal fold granuloma (VFG) is used as it is a broad term than vocal process granuloma (VPG) which restricts the site of the lesion on the vocal process of the arytenoid cartilage while in research; it was found a variety of VFG locations in posterior glottis.

In the current study Males are highly affected than female with male to female ratio 4:1. Despite there is no convincing explanation for this phenomenon in articles but with discussing cases of post intubation, change of the ration on expense of females was detected, it could be explained that as a result of decreased intermemberanous to intercartilagenous ratio during adduction in females than in males that makes female larynx (specially posterior region) more vulnerable to trauma by endotracheal tubes.7,15 It could be hypothesized that increased incidence of GERD in males than in females with increased tobacco and caffeine consumption, and eating habits of males in Egypt may explain this observation. These results coincided with many other studies.1,7,15

In the present study the identified etiologic factor in 26 (61.9%) of the cases was GER, 6(14.3%) had had laryngeal intubation, 4(9.5%) were vocal abuse and 6(14.3%) were considered idiopathic. While it is widely held that vocal process granulomas occur following intubation trauma and vocal fold abuse, Havas et al.,10 supported the view that laryngopharyngeal reflux plays a most important role in granuloma etiology and propagation. Upon their voice clinic experience, hyperfunctional voice abuse alone has rarely been seen to be a cause of VPG. Patients with poor vocal patterns tend to develop a muscle tension dysphonia rather than a granuloma. So they postulated that in the absence of GERD, functional laryngeal irritation is not sufficient to cause desquamation and has not ability to develop granuloma. Havas suppose could explain the high resistance of post intubation posterior VFG that was reported in the patients who did not excluded from having concomitant GERD before being included in the study (Table 4). Zhang et al.,16 noted the high recurrence rate of granuloma after surgical removal and suggested that gastroesophageal reflux could play a role in pathogenesis.

Dysphonia was the most common complaint that presented in 66.7% of patients. As VFG is a posterior glottis lesion that affects the cartilaginous portion of the glottis, it is suspected to preserve the voice being away from the membranous portion but large volume lesions (even extremely posterior) in the current study do. This finding matched with Lemos et al.,15 and Rimoli et al.,7 who reported dysphonia as the main complaint in 47.26% and 95% of their patients respectively. Being a recurrent lesion with long history and previous interference all patients involved in the current study had symptoms that mainly related to the etiology rather than specific to VFG itself except of dysphonia and difficulty of breathing that presented in 4patients (9.5%) as it was related to the lesion size (Table 2). In other words, chronic cough, globus sensation, odynophagia, and throat clearing in cases of VFG are etiological related symptoms.

On the other hand, on identifying the relation between different etiologic factors and the rate of complete remission without need to surgical excision (Table 4), patients with GERD, vocal abuse/misuse, and idiopathic cases showed the most favorable results with 92.31% of patients having GERD did not need further interferences as seen in all patients of the other two etiologies. On the same time patients with post-intubation granuloma showed the worst result as all of them were responding to conservative management to a lesser extent. It could be explained by that conservative management was directed specifically to GERD which reported as the most-important factor in VFG pathology in addition to early presence of GER in those patients as a concomitant etiology. Conservative treatment regimen applied in the present study achieved complete remission in 80.95% of subjects within a mean period of 13.88±5.4 months of maximum 24months that reported to be the maximum period permitted for spontaneous remission under optimal conservative management. There was no other article that identified the maximum permissible duration for complete remission among patients with VFG.

Upon discussing the study's conservative regimen; the behavior modification techniques, including both voice hygiene education and anti-GER measures, aimed to reduce both chronic functional (mechanical) and chemical laryngeal irritation. Voice therapy aimed to reduce hyperfunction muscular activity, elevate the pitch up to a comfortable level, and increase the number of vocal inflections. These measures reduce the aggression to the arytenoid vocal process, allowing improvement.17,18 PPI aimed to reduce gastric refluxant amount and contents (PH) and it is reported to be more efficient than anti-histaminic H219 while MosaprideTM aimed to eliminate the underlying prechondritis. Treatment with steriods has good response in granulomas, and it may be the first treatment before surgical intervention.10 One out of 8 subjected (12.5%) that showed resistance to conservative treatment and subjected to surgical excision with intralesional injection of long acting steroid showed post-operative recurrence that explained by having major gastroesophageal problem indicating laparoscopic fundoplication. Intraoperative intralesional long acting steroid injection aimed to eliminate the inflammatory process further than the prechondritis.

Vocal fold granuloma is a lesion that well responds to conservative treatment with complete recovery of maximum period of 24months even if it is large and recurrent. Laryngeal granuloma has high recurrence rate after early surgical removal. It affects mainly men, except for cases associated with laryngeal intubation. The term vocal fold granuloma (VFG) is broader than the term vocal process granuloma (VPG) that a variety of VFG locations in posterior glottis are found. Managing patients with recurrent large posterior vocal fold granuloma needs interdisciplinary team that involves an otolaryngologist, phoniatrician, gastroenterologist, and gastrointestinal surgeon. Laryngoscopy and ambulatory pH manometry are essential for assessment and follow-up. The main etiopathogenic factor associated was GER followed by laryngeal intubation. Voice abuse alone couldn't evoke the condition. Systemic and local steroids are as important as anti-reflux medication in treatment of VFG. Voice therapy cannot be overlooked.

An informed consent using appropriate language was taken before starting the study. It included Study title, Performance sites, Purpose of the study, Study procedures, Benefits, Risks, Right to refuse and Signature.

I would like to express my deepest thanks to all subjects for their cooperation and the associates who helped within the work.

No conflicts of interest declared.

This research was carried out without funding.

©2019 Ezzat. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.