Journal of

eISSN: 2471-1381

Mini Review Volume 2 Issue 2

Division of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, Childrens Hospital of Pittsburgh, USA

Correspondence: Zahida Khan, Childrens Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC, Division of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition 4401 Penn Avenue, Faculty Pavilion 6th Floor, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA,, Fax 281-854-8390

Received: March 11, 2016 | Published: May 17, 2016

Citation: Khan Z. Pathogenesis of alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency in the liver: new approaches to old questions. J Liver Res Disord Ther. 2016;2(2):44-49. DOI: 10.15406/jlrdt.2016.02.00023

Alpha-1 Antitrypsin deficiency (A1ATD) can progress to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma; however, not all patients are susceptible to severe liver disease. Liver transplantation is the only cure for A1ATD-related liver disease. A1ATD is caused by a toxic gain-of-function mutation in the human SERPINA1 gene, generating mis folded ATZ protein “globules” in hepatocytes. These insoluble aggregates overwhelm protein clearance pathways and lead to chronic intracellular stress. This review serves to summarize the basic hepatic mechanisms involved in A1ATD, as described in relevant in vitro and animal models. Potential treatments such as autophagy-enhancing agents and molecular therapies are also discussed. Clinical trials are underway to further assess some of these novel approaches in patients, but more safety and efficacy data is needed to successfully translate these interventions from the laboratory to the clinic.

Keywords: PIZ mouse, autophagy, ATZ globule, carbamazepine, C. Elegans, liver transplantation, PASD, SERPINA1, TFEB

A1ATD, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency; A1AT, alpha-1 antitrypsin; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; PAS, periodic acid schiff; SNPs, single nucleotide polymorphisms; ERManI, ER mannosidase I; IPSC, induced pluripotent stem cell; GC, globule-containing; GD, globule devoid; 4-PBA, 4-phenylbutyric acid; GFP, green fluorescent protein; LOPAC, library of pharmacologically active compounds

At the time of this writing, there are over 15,000 patients awaiting liver transplantation in the USA, but only 6729 liver transplants were performed last year.1 Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency (A1ATD) is the most common inherited cause of pediatric liver disease and transplantation. Liver transplantation remains the only treatment for patients with severe liver disease; however, it is difficult to predict which factors predispose some patients to develop liver disease while sparing others. For example, prospective studies of a Swedish cohort of 127 A1ATD patients identified by mass neonatal screening reported that ~8% of homozygotes develop clinically significant liver disease over their lifetime.2‒4 This suggests the role of other genetic and/or environmental modifiers of disease susceptibility.

The classical form of A1ATD is an autosomal co-dominant disorder that affects as many as 1 in 3000 live births in the United States and Europe.5 Normal human Alpha-1 Antitrypsin (A1AT) is a 52-kDa glycoprotein of the serpin family, predominantly produced in the liver and released into the blood. In affected patients, circulating levels of mutant ≤15% A1AT of normal are protein levels. Serum A1AT acts as an acute phase reactant and it functions to inhibit destructive neutrophil elastase in the lung; therefore, deficiency of the serum protein leaves the lungs exposed to damage. Mutant ATZ leads to respiratory cell proteinopathy and fibrosis later in life.6

The most common genetic defect in A1ATD involves homo zygosity for the Z allele (ZZ, causing Pi*ZZ phenotype) in the SERPINA1 gene on human chromosome. This single base pair substitution encodes a glutamate lysine mutation at position 342.7 This change in negative-to-positive charge results in a toxic gain-of-function mutation (ATZ), leading to conformational changes in the secondary and tertiary structure of the protein. Mis folded ATZ monomers accumulate in the Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) of hepatocytes, forming insoluble globules that are Periodic Acid–Schiff (PAS)+/diastase-resistant. ER protein degradation pathways, involving either autophagy or proteasomes, become overwhelmed. As the ATZ globules accumulate in the liver, chronic hepatocyte injury from ER stress, mitochondrial damage, and impaired protein clearance can progress to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in some individuals.8 Modifiers of disease susceptibility are therefore a focus of active investigation, especially in the age of “big data”. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the SERPINA1 gene have been identified in children with PiZZ phenotype and moderate-to-severe liver disease.9 Critical ER proteins that control ATZ degradation include the transmembrane chaperone calnexin and the enzyme ER Mannosidase I (ERManI), both of which have been implicated in reduced efficiency of degradation using cell lines derived from PiZ patients susceptible to liver disease.10‒13 These molecular findings are promising, but also highlight the question of how these biological processes can be harnessed to aid in the treatment and prognosis of A1ATD liver disease. Several laboratory models have been developed to further explore these pathways.

Disease models of A1ATD liver disease

Traditional models of A1ATD range from stably transfection cell lines to transgenic mice. Although these models and well-characterized, they may not efficiently fulfil the growing need for multiplex drug screening and personalized pharmacogenetics. To expedite translation of new potential therapies to the clinic, recent generation of effective rapid screening models have now been established. As personalized medicine evolves, complementary models of metabolic liver disease, such as patient-derived induced pluripotent stem (IPS) cells and mice with “humanized” livers, are in the pipeline, and will be innovative for the study of patient-specific variations and disease phenotypes in A1ATD. The primary models of A1ATD liver disease in the literature are reviewed below.

In vitro models of A1ATD

Mammalian cell lines have been used extensively to study the complex intracellular processing of mis folded ATZ proteins. Detailed sub cellular analysis in mouse hepatoma cell lines transfection with human ATZ expression vectors revealed that degradation of mutant ATZ proteins localizes within ER-to-Golgi vesicle trafficking in the early secretory pathway.14 Proteostasis is a dynamic process. Although insoluble macromolecular complexes form ATZ aggregates, smaller soluble forms do exist within the ER where they are subject to degradation pathways, possibly playing a role in maintaining protein quality control.15 As in PiZ mice, treatment of ATZ-expressing human cell lines with autophagy-enhancing agents reduced ATZ aggregates.16 The opposite effect is observed when treating the same cells with inhibitors of autophagy, or when studying autophagy-deficient cell lines and yeast strains.17,18

More recent work has focused on induced pluripotent stem cell (IPSC) lines as a method of modelling a wide range of monogenic metabolic liver diseases, including A1ATD. Direct reprogramming of somatic cells from PiZ mice was the first “proof-of-principle” step in developing an IPSC model.19 The technique was soon adapted to patient-derived iPSCs that could be differentiated into hepatocytes, allowing a novel platform to study variations in A1ATD disease modifiers and phenotype.20 Tafaleng et al.20 demonstrated that IPSC hepatocytes recapitulate the accumulation and processing of ATZ globules found in patients with severe liver disease.20 With scaled up differentiation protocols, patient-derived IPSC hepatocytes could also provide an unlimited source for drug discovery and screening, paving the way for personalized medicine. Wilson et al.21 recently identified 135 genetic modifiers of severe liver disease via global transcriptome analysis of IPSC hepatocytes.21 These cells also showed a favorable autophagy response to autophagy-enhancing agents in culture. Another potential application for IPSC hepatocytes is cellular and gene therapy.22

PiZ mouse model of A1ATD

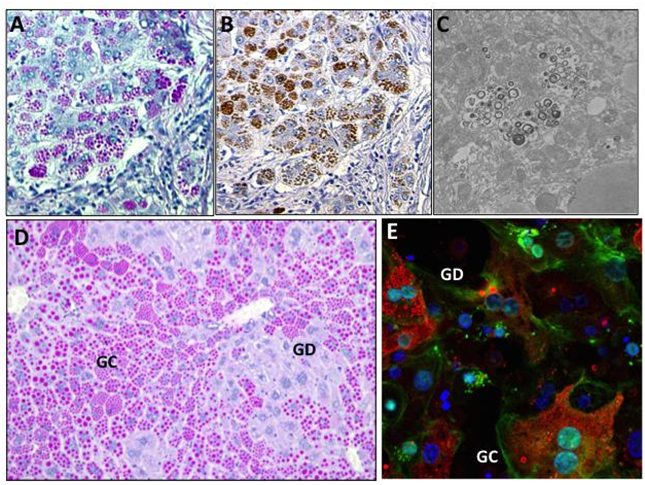

Despite knowing the molecular defect in A1ATD, there are still many unanswered questions about specific modifiers of disease severity and susceptibility. The clinical variability of liver disease in patients with A1ATD may be related to phenotypic differences at the cellular level. In PiZ hepatocytes, the balance of proteostasis, including autophagy and other protein degradation pathways, influences susceptibility to or protection from toxic ER stress.4,23 Histologically, there are two main hepatocyte subpopulations in A1ATD, described as “globule-containing” (GC) or “globule-devoid” (GD) cells (Figure 1), with distinct characteristics.

A. PASD stain highlights ATZ globules (pink) in a human explanted liver from a pediatric patient with severe liver disease (100x). B. A1AT immunohistochemistry of ATZ globules in serial section of A (100x). C. EM of pediatric liver explant showing accumulation of autophagolysosomes (15000x). D. PASD stain of PiZZ transgenic mouse liver highlights globule-containing (GC) and globule-devoid (GD) cells (100x). E. Confocal immunofluorescence staining of isolated primary PiZZ mouse hepatocytes in culture, showing A1AT (red) globules, DAPI (blue) nuclear stain, and phalloidin (green) actin cytoskeletal stain (200x). In general, hepatocytes contain a range of small, large, intermediate, or no ATZ globules.

From a cell biology perspective, the differential capabilities of GC and GD hepatocytes have been described in the well-established PiZ transgenic mouse strain, which over-expresses human ATZ (note that “PiZ” refers to having 2 copies of the transgene). The transgene consists of multiple genomic fragments of DNA that contain the coding regions of the human ATZ gene together with introns and ~2 kilo bases of upstream and downstream flanking regions.24 The transgene is expressed primarily in liver, making this a pure toxic gain-of-function model of hepatocyte ER stress.24,25 Minor levels are also found in other tissues known to express A1AT. Of note, the wild-type murine A1AT is still expressed in this model; therefore, serum levels of endogenous A1AT are preserved and the lungs are relatively protected.

In the PiZ transgenic mouse, GC hepatocytes are replaced over time with less stressed GD hepatocytes, making this an ideal model to investigate the differential capabilities of these two cell types (Figure 1D) (Figure 1E). Functionally, PiZZ mice have reduced hepatic glycogen stores and impaired fasting tolerance.26,27 At the tissue level, they develop low-grade hepatic inflammation, regeneration, steatosis, and even malignancies as they age, recapitulating the classical liver disease found in A1ATD patients.16,28 Mela et al.29 analyzed liver biopsies from 60 A1ATD patients with varying degrees of fibrosis, and found significantly larger hepatocyte nuclei and shorter telomere length, both markers of senescence, in A1ATD human hepatocytes compared to age- and sex-matched control liver tissues.29 PiZZ patients had significantly more changes than PiZ heterozygotes, suggesting a proteotoxic effect. Similar changes were noted in GC cells compared to adjacent GD cells within the same human tissue sections. These findings were associated with increased patient age, ATZ globule content, and fibrosis.

Several studies have investigated the pathogenesis of A1ATD in detail using the PiZ mouse. Comparable to humans, aging liver tissue from older PiZ mice contains increased reactive oxygen species, lower levels of protective antioxidant enzymes, and evidence of cellular damage when compared to younger mice.30 Interestingly, hepatotoxicity from ATZ globule accumulation is more severe in male PiZ mice compared to females, which parallels the disease spectrum found in humans.31,32 In fact, testosterone treatment of female PiZ mice increased ATZ expression and hepatocellular proliferation to a level comparable with that observed in males.31 Rudnick et al.31 found that although intracellular accumulation of ATZ globules is associated with a regenerative stimulus, GD cells still demonstrated a proliferative advantage over GC cells.31 Similarly, Ding et al.33 used cell transplantation to demonstrate that wild-type and to some extent GD hepatocytes have a proliferative advantage over GC hepatocytes.33 Isolated PiZ mouse hepatocytes are susceptible to decreased proliferation and increased apoptosis with increasing ATZ globule load.34,35 Taken together, these studies confirm that GD hepatocytes exhibit increased survival and regenerative capacity in times of stress.

As a preclinical model, the PiZ mouse offers a unique opportunity to study mechanisms of protein clearance of ATZ globules. Impaired autophagy is the major intracellular pathway implicated in A1ATD. During autophagy, autophagosomes engulf cytoplasmic components, such as cytosolic proteins and organelles, marked for degradation.36 Although starvation-induced autophagy is an evolutionarily conserved survival mechanism, fasting in PiZ mice leads to poor outcomes and no increase in hepatic autophagy.27 Baseline autophagosomes activity is observed in the liver of PiZ transgenic mice and in liver biopsy specimens from patients with A1ATD.37 Interestingly, it has been shown that the transcription factor TFEB appears to be a master regulator of autophagy and lysosomal biogenesis. The nutrient-sensing kinase enzyme mTORC1, a regulator of starvation-induced autophagy, phosphorylates cytoplasmic TFEB in fed conditions.38 Cytoplasmic TFEB is de phosphorylated in the fasted state, and translocates to the nucleus to induce autophagy-related gene expression. TFEB gene transfer in PiZ mice induced macro autophagy and corrected the liver disease, leading to increased degradation of polymerized ATZ in auto lysosomes and decreased expression of ATZ monomers.39

From a clinical perspective, recent studies have focused more on autophagy-enhancing agents to induce ATZ disposal. Rapamycin given in weekly pulses was the first drug reported to increase autophagic activity and reduce intrahepatic accumulation of polymerized ATZ proteins.40 Rapamycin is an mTOR inhibitor clinically in use as a potent immuno suppressant, but can have serious complications including lung toxicity. Hidvegi et al.16 examined the effects of carbamazepine (CBZ), a well-known FDA-approved anticonvulsant and mood stabilizer with an extensive safety profile, in PiZ mice.16 CBZ mediated a reduction on hepatic ATZ globule load and ameliorated hepatic fibrosis in PiZ mouse liver, making it an ideal therapeutic strategy. Currently, a Phase II/III clinical trial for the use of CBZ in severe A1ATD liver disease is ongoing, with dosing of 1200mg/day for subjects over 15years of age (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01379469). Members of the phenothiazine class of drugs, such as fluphenazine, also have combined autophagy-enhancing and mood stabilizing effects.41 As with CBZ, fluphenazine treatment in PiZ mice reduced the accumulation of ATZ in the liver and mediated a decrease in hepatic fibrosis, making it another promising agent.41 Synthetic bile acids, many of which are in clinical trials for treating other chronic liver diseases, have recently demonstrated potential benefits for inducing autophagic clearance of ATZ globules in PiZ mice.42

elegans model of A1ATD

It should be noted that identification of many of the above autophagy-enhancing agents would not have been possible without initial automated high-throughput live animal drug screening in roundworms.43C. elegans is a transparent nematode that is ~1-mm in length. Although C. elegans is a simple un segmented pseudocoelomate that lacks respiratory, circulatory, and hepatobiliary systems, it can be genetically engineered to express fluorescently-tagged wild-type (ATM) or Z mutant forms (ATZ) of the human SERPINA1 gene fused to green fluorescent protein (GFP).44 These animals secrete soluble ATM, but retain polymerized ATZ protein within dilated ER cisternae.44 Transgenic ATZ-expressing worms exhibit slow growth, smaller brood size, and decreased longevity, similar to PiZ mice (Figure 2). This novel C. elegans model has been adapted for screening a library of 1280 compounds in the Library of Pharmacologically Active Compounds (LOPAC), to identify drugs in active clinical use that could be immediately tested in clinical trials and “repurposed” for treating A1ATD-associated liver disease.43

Molecular therapies for liver disease in A1ATD45‒51

Gene therapy for A1ATD liver disease: Several approaches to gene therapy for A1ATD are under investigation (Table 1). One strategy involves targeted “knock-down” of the mutant ATZ gene, which has been studied both in vitro and in PiZ mice. In IPSC hepatocytes derived from patients with severe liver disease, Lentiviral vector-mediated expression of short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) directed against the ATZ led to a 66% reduction in intracellular ATZ protein, which was functionally relevant and efficiently maintained with hepatocyte differentiation.22 This opens up future possibilities for ex vivo targeted gene correction and autologous cell therapy. Recent studies have also focused on anti-sense oligonucleotides to effectively target and reduce human ATZ expression in PiZ mice.52 Short-term administration in these animals stopped liver disease progression, while long-term treatment reversed liver disease and decreased fibrosis. Administration in non-human primates led to a ~80% reduction in levels of circulating normal AAT, demonstrating potential for this approach in higher species.53 Repeat dosing had long-lasting effects, preventing and even reversing accumulation of ATZ aggregates in PiZ mice and cynomolgus monkeys.54 Finally, Micro RNA (MiRNA) “dual therapy” has also been studied in PiZ mice, where effective knock-down of mutant ATZ is accompanied by expression of wild-type A1AT (ATM).55 miRNA dual therapy led to decreased hepatic inflammation and ATZ globule accumulation, with concomitant increase in normal serum A1AT. A clinical trial is now under way to further investigate antisense oligonucleotides as a potential therapy for A1ATD liver disease in adult patients (ClinicalTrails.gov, NCT02363946).

Therapeutic Agent |

Therapeutic Mechanism |

Methodology |

Clinical Trial ID |

Current Status |

References |

Carbamazepine (CBZ) |

Mood stabilizer and anti-epileptic drug that enhances autophagy to increase ATZ protein clearance |

Phase 2, interventional |

NCT01379469 |

Recruiting |

|

ALN-AAT |

RNAi-based knockdown of ATZ protein expression |

Phase 1/2, interventional |

NCT02503683 |

Recruiting |

|

ARC-AAT |

RNAi-based knockdown of ATZ protein expression |

Phase 1, interventional |

NCT02363946 |

Recruiting |

|

rAAV1-CB-hAAT gene vector |

AAV gene transfer of normal A1AT into muscle cells |

Phase 1, interventional |

NCT00430768 |

Completed |

[46-49] |

rAAV1-CB-hAAT gene vector |

Phase 2, interventional |

NCT01054339 |

Active, not recruiting |

||

rAAV2-CB-hAAT gene vector |

Phase 1, interventional |

NCT00377416 |

Active, not recruiting |

||

4-phenyl butyrate (4-PBA) |

Molecular chaperone to increase ATZ protein secretion from liver |

Phase 2, interventional |

NCT00067756 |

Completed |

Table 1Clinical studies listed in ClinicalTrials.gov for therapy of liver disease in A1ATD.45

Protein-directed therapy for A1ATD: In addition to enhancing autophagic degradation, proteinopathies can be managed by increasing the endogenous protein (i.e., increasing production, correcting mis folding and increasing secretion) or by replacing with functional exogenous protein. Although A1AT is an acute phase reactant that increases with fever, shock, trauma, or pregnancy, pharmacologic strategies to enhance endogenous production in deficient patients have not proven to be effective.56 Though not discussed here, intravenous augmentation using pooled human A1AT is currently the most direct and efficient means of elevating A1AT levels in the plasma and in the lung interstitium in adults.5 Another attractive liver-based strategy is the use of chemical chaperones to correct protein mis folding. 4-phenylbutyric acid (4-PBA), used safely as an ammonia scavenger in patients with urea cycle disorders, partially corrected deficient circulating levels of ATZ in PiZ mice.50 Increased secretion of ATZ protein was also observed in cultured cells treated with 4-PBA. Despite this reversal of protein mis folding, a randomized controlled trial of oral 4-PBA did not increase serum protein levels in patients, and symptomatic and metabolic side effects were significant.51

Since the first description of A1ATD over 50years ago, significant progress has been made in understanding the basic pathobiology of both the liver and lung disease. Despite these achievements, current management primarily involves supportive measures, such as augmentation therapy for lung disease. Transplantation is still the only cure for severe chronic liver and/or lung disease. Recent findings on intracellular protein processing and autophagy have identified novel therapies to prevent liver damage from ATZ accumulation; however, strategies to alter gene expression and protein secretion are still under investigation. Further work is needed comparing both genome-wide associations as well as personalized patient-specific variations. Understanding these mechanisms at the molecular level will help shed light on modifiers of disease susceptibility in patients with A1ATD.

Dr. Khan acknowledges grant support from NIH/NICHD PHS K12HD052892, the Alpha-1 Foundation, and the Hillman Foundation. Dr. Khan also acknowledges assistance with Figure 1 from Dr. Donna B. Stolz (University of Pittsburgh’s Center for Biologic Imaging, Core A), as well as from Dr. Sarangarajan Ranganathan (Pathology Department, Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh).

Author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

©2016 Khan. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.