Journal of

eISSN: 2376-0060

Case Series Volume 8 Issue 3

1Division of Acute Care Surgery, Department of Surgery, Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, USA

2Rutgers Ernest Mario School of Pharmacy, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, USA

3Division of Acute Care Surgery, Froedtert Memorial Lutheran Hospital, Medical College of Wisconsin, USA

4Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, Rutgers School of Public Health, USA

Correspondence: Rachel L. Choron, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Surgery, Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, 125 Patterson Street, Suite 6300, New Brunswick, NJ 08901, USA

Received: June 09, 2021 | Published: September 3, 2021

Citation: Choron RL, Iacono S, Maharaja K, et al. Continuation of therapeutic anticoagulation before and during hospitalization is associated with reduced mortality in COVID-19 ICU patients. J Lung Pulm Respir Res. 2021;8(3):120-130. DOI: 10.15406/jlprr.2021.08.00263

Background: Literature has well established COVID-19 associated coagulopathy with resulting thrombotic complications including microthrombi as an underlying mechanism leading to severe respiratory disease. Therapeutic anticoagulation (TAC) for COVID-19 patients has therefore been widely trialed to combat COVID-19’s coagulopathic effects. However, literature has yet to define which population of patients TAC benefits; the most current randomized controlled trials (RCTs) reveal TAC to be possibly beneficial to moderately-ill hospitalized COVID-19 patients, whereas benefits did not outweigh risks in critically-ill ICU patients. Importantly, these studies excluded patients who received prehospital TAC. We examined outcomes in critically ill COVID-19 ICU patients who received TAC vs prophylactic anticoagulation (PAC) and specifically whether prehospital TAC effected outcomes.

Methods: Retrospective cohort study of 132 COVID-19 ICU patients admitted March-June, 2020. Initial clinical practice provided PAC, as literature demonstrating COVID-19 associated coagulopathy and increased thromboembolic complications emerged, a TAC protocol was initiated.

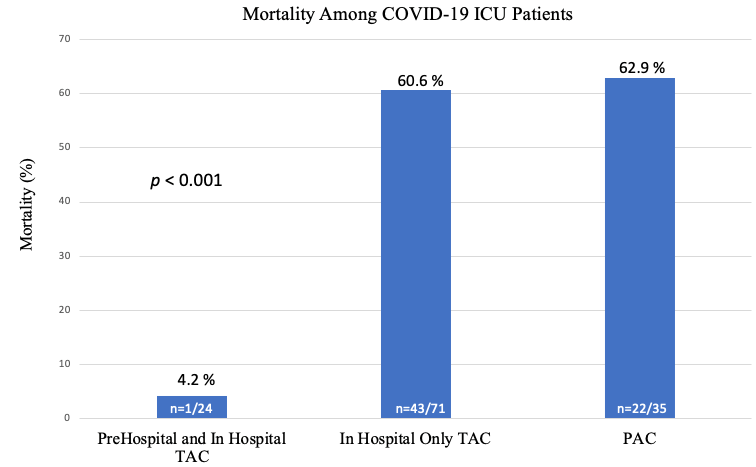

Results: 130 patients were included in the study, 95 of whom received TAC and 35 PAC. There was 50.8% overall mortality, with lower mortality in the TAC vs PAC group (46.3% vs 62.9%, p=0.094). There were few thromboembolic and hemorrhagic complications, with no significant difference between TAC and PAC patients. Of 24 patients anticoagulated prior to and during hospitalization, only 1 (4.2%) died, whereas the mortality was 60.6% among patients therapeutically anticoagulated during hospitalization only (p<0.001). Multivariable analysis revealed patients who received prehospital and in hospital TAC had a 92% lower risk of death (p=0.008) compared to in hospital only TAC and PAC patients.

Conclusions: Overall, therapeutic anticoagulation did not result in mortality benefit to COVID-19 ICU patients compared to prophylactic anticoagulation. However, a sub-population of patients who received TAC both prior to and during hospitalization had a 12-fold lower risk of death. This suggests a protective effect of TAC when it is continued before and during hospitalization. RCTs are needed to specifically examine this subset of COVID-19 patients.

Keywords: COVID-19, critical care, anticoagulation, thromboembolism, mortality

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was first reported in Wuhan, China in December 2019 and by March 11th, 2020 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) was designated a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO).1 Now, over 216 million cases of COVID-19 have been confirmed world-wide, including over 38 million cases and 630,000 deaths in the United States alone.2,3

Mortality rates in COVID-19 intensive care unit (ICU) patients are high with recent meta-analyses revealing a 39% mortality rate.4-6 As the pandemic progressed and the death toll continued to rise, research focused on potential therapeutic interventions to improve outcomes. The identification of COVID-19 associated coagulopathy led to anticoagulation as one potential treatment modality.

Recent literature identified laboratory associated coagulopathy in COVID-19 patients with high concentrations of coagulation biomarkers including D-dimer, fibrinogen, von Willebrand Factor, and thrombin anti-thrombin complex.7 Studies also demonstrated elevated D-dimer and prothrombin time were associated with increased COVID-19 mortality.8,9 Clinical manifestations of COVID-19 associated coagulopathy were inferred as patients developed higher rates of venous thromboembolism (VTE) compared to non-COVID patients; this included higher rates of deep vein thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolism (PE), mesenteric ischemia, lower limb ischemia, and cerebral ischemia.10,11 Autopsy reports also revealed a higher than normal incidence of DVT and PE among COVID-19 patients.12-14 In addition, post-mortem computed tomography (CT) scans revealed diffuse alveolar damage and tissue samples with endothelial vascular injury and widespread thrombosis and microthrombi were nine times more prevalent when compared to non-COVID-19 patients.14

Anticoagulants, such as heparinoids, reduce inflammation and the toxicity of histones on endothelial tight junctions decreasing lung edema and vascular leakage,15 therefore attenuating the hypercoagulable state induced by infection.8 Prophylactic anticoagulation provided to COVID-19 patients with sepsis induced coagulopathy (SIC) Score of ≥ 4 resulted in lower D-dimer levels and 20% lower mortality as compared to COVID-19 patients not treated with prophylactic anticoagulation.8 In this setting the International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) and the WHO instituted guidelines for VTE chemoprophylaxis.15-17 In COVID-19 patients at higher risk for VTE, higher anticoagulation doses were recommended.15,17,18

There are currently three platforms aligned enrolling hospitalized COVID-19 patients in a randomized controlled trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04372589) evaluating whether full dose anticoagulation reduces mortality and days free of organ support. This trial examined different subsets of patients including critically ill ICU patients, moderately ill hospitalized patients, and mildly effected patients. Importantly, this trial does not include patients who were on anticoagulation prior to hospitalization or those on anticoagulation for indications other than COVID-19 coagulopathy.

We hypothesized that COVID-19 patients with respiratory failure who received therapeutic anticoagulation had lower mortality than those who received prophylactic anticoagulation. Our secondary goal was to examine the patients who were excluded from the ongoing randomized controlled trials who received therapeutic anticoagulation prehospitalization and compare outcomes to those who received therapeutic or prophylactic anticoagulation during hospitalization alone.

Patient population and setting

We performed a retrospective, single center, observational study of the first 132 consecutive COVID-19 positive patients admitted to the ICU with respiratory failure. Patients were included from March 11, 2020 to June 11, 2020. The Institutional Review Board approved this observational study.

Final follow-up date was July 13th, 2020. At the study endpoint, 130 of 132 patients met inclusion criteria with confirmed COVID-19 by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of nasopharyngeal sample and discharge from the ICU or death by the final date of follow-up. Two patients remained admitted to the ICU at the study endpoint and were therefore excluded.

This study was performed at a 297-bed community hospital in central New Jersey. The ICU capacity prior to COVID-19 was 16 beds with a typical census of 10 patients. During the height of the pandemic, the ICU was expanded with the census peaking at 42 patients in mid-April. All critically ill COVID-19 patients were cared for by a multidisciplinary team led by a board certified intensivist 24 hours a day.

Anticoagulation protocol

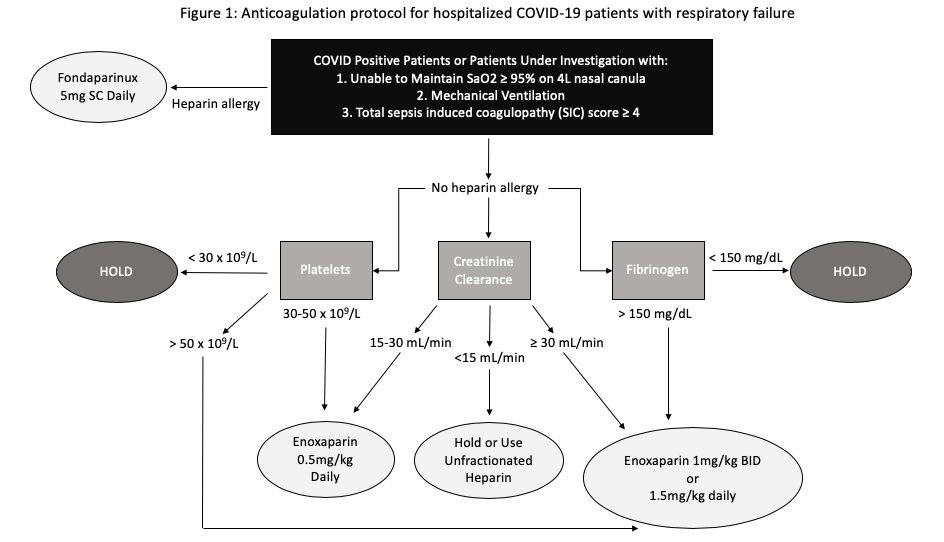

The initial clinical practice pattern at the beginning of the study period was to provide PAC to COVID-19 patients in respiratory failure admitted to the ICU. PAC during the early COVID-19 pandemic consisted of traditionally dosed VTE prophylactic therapy or occasionally intermediate-dose enoxaparin 0.5mg/kg subcutaneously (SC) twice daily (BID) or 1mg/kg SC daily. This practice pattern changed once a TAC protocol was adopted by the critical care division on April 6, 2020. This protocol was designed by a multi-disciplinary ad hoc committee based on recommendations as described above. All COVID-19 positive patients or patients under investigation (PUI) unable to maintain peripheral oxygen saturation (SaO2) >95% on 4 liters (L) nasal cannula, requiring mechanical ventilation, or with a SIC score ≥ 4 received TAC. The TAC protocol utilized enoxaparin 1mg/kg SC BID or 1.5mg/kg daily, or alternatively unfractionated heparin (UFH) infusion for those not candidates for Enoxaparin. Patients with a documented heparin allergy received therapeutic doses of fondaparinux 5mg subcutaneous injection daily (Figure 1). Dose adjustments were made for patients with organ failure and thrombocytopenia respectively. Patients with fibrinogen levels less than 150 mg/dL were not given anticoagulant therapy. Patients who were on TAC prior to the initiation of the protocol were maintained on TAC and analyzed as part of the TAC group.

Figure 1 A depiction of the therapeutic anticoagulation protocol used for COVID-19 patients with respiratory failure.

Patients were monitored for signs of bleeding while on TAC. TAC was held if patients met any of the following criteria: hemoglobin decrease > 2g/L within 24 hours, observed bleeding, planned invasive procedure per physician discretion, or HAS-BLED Score ≥3. TAC was continued for at least 7 days, until extubation, or if any adverse hemorrhagic event occurred.

Patients who were treated with anticoagulation prior to hospitalization as an outpatient along with TAC during hospitalization were defined as “prehospital and in hospital TAC.” Patients whose confirmed outpatient medications did not include anticoagulation but received TAC during hospitalization were defined as “in hospital only TAC.”

Data collection and definitions

Patient information was collected from the electronic medical record (Allscripts-Sunrise Clinical Manager, Chicago, IL). The data collected included patient demographics, past medical history, prior anticoagulant use, initial vital signs, imaging, laboratory testing, presenting symptoms, and therapies received for COVID treatment. Chart review was conducted to collect information on patient disposition, ICU length of stay, hospital length of stay, ventilator days, days hospitalized prior to intubation, and mortality. Complications collected included acute kidney injury as defined by the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) definition,19 acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) defined by the Berlin criteria,20 culture proven infection, and imaging proven thrombotic and hemorrhagic events. Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) was defined as thrombosis within the deep veins identified on venous duplex ultrasonography of the lower or upper extremities. Pulmonary embolism (PE) was defined as thrombosis in the pulmonary arteries identified on computed tomography angiography of the chest.

Statistical analysis

The distributions of baseline characteristics, vital signs, laboratory results, treatments, and outcomes were computed for the entire study population, for patients who received TAC (all TAC patients, prehospital and in hospital TAC patients, and in hospital only TAC patients), and for patients who received PAC. Frequency and percentages are reported for categorical variables, and median and interquartile range (IQR) are reported for continuous variables. Since nearly all were determined to be non-normally distributed according to the Shapiro-Wilk statistic. Bivariate comparisons of categorical and continuous variables were tested using Pearson’s chi-square statistic (or Fisher’s exact test when warranted by small cell counts) or two-sided Wilcoxon Rank-Sum statistics, respectively. Adjusted relative risks were computed using multivariable modified (robust variance estimator) Poisson regression models. Survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

At the final date of follow-up, 130 COVID-19 positive ICU patients met study inclusion criteria. Of the total ICU population observed, 95 patients received TAC and 35 patients received PAC. Patients who were placed on TAC underwent therapy for a median of 11 days. The majority of these patients received enoxaparin (65.3%), 31.6% received therapeutic unfractionated heparin, and 3.2% received other forms of therapeutic anticoagulation. Twenty-four patients received prehospital and in hospital TAC and 71 patients received in hospital only TAC.

Patient characteristics

The median age was 63 years in TAC patients [range 25-89, IQR 17] and 64 years [range 34-86, IQR 19] in the PAC group (p=0.809). A higher percentage of patients were male in both TAC and PAC groups (63.2% vs 77.1%; p=0.133). The majority of patients were Caucasian (45.4%), followed closely by Hispanic patients (33.1%). A higher proportion of Hispanic patients received TAC compared to Caucasians (Table 1).

|

|

All COVID-19 ICU Patients (n=130) |

Among All Patients |

Among TAC Patients |

||||

|

All TAC (n=95) |

PAC (n=35) |

p value |

TAC Prehospital and In hospital (n=24) |

TAC In Hospital Only (n=71) |

p value |

||

|

Age, median (IQR) [range], years |

64 (17) [25-89] |

63 (17) [25-89] |

64 (19) [34-86] |

0.809 |

62 (14) [29-78] |

64 (18) [25-89] |

0.099 |

|

Sex, male (n, %) |

87 (66.9) |

60 (63.2) |

27 (77.1) |

0.133 |

16 (66.7) |

44 (62.0) |

0.680 |

|

Race/Ethnicitya |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Caucasian |

59 (45.4) |

37 (39) |

22 (62.9) |

0.056 |

10 (41.7) |

27 (38.0) |

0.253 |

|

Black |

17 (13.1) |

12 (12.6) |

5 (14.3) |

|

4 (16.7) |

8 (11.3) |

|

|

Hispanic |

43 (33.1) |

37 (39) |

6 (17.1) |

|

6 (25) |

31 (43.7) |

|

|

Asian |

11 (8.5) |

9 (9.5) |

2 (5.7) |

|

4 (16.7) |

5 (7) |

|

|

Comorbiditiesb |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

None |

21 (16.2) |

16 (16.8) |

5 (14.3) |

0.725 |

4 (16.7) |

12 (16.9) |

0.247 |

|

Chronic Respiratory Disease |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

COPD/Asthma |

14 (10.8) |

8 (8.4) |

6 (17.1) |

0.201 |

1 (4.2) |

7 (9.9) |

0.675 |

|

Obstructive Sleep Apnea |

9 (6.9) |

7 (7.5) |

2 (5.7) |

1.000 |

1 (4.2) |

6 (8.6) |

0.674 |

|

Diabetes |

56 (43.1) |

42 (44.7) |

14 (40.0) |

0.633 |

12 (50) |

30 (42.9) |

0.544 |

|

Obesity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Body Mass Index > 30 kg/m2 |

65 (50.0) |

48 (52.8) |

17 (50) |

0.784 |

13 (56.5) |

35 (51.5) |

0.675 |

|

Cardiovascular Disease |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hypertension |

81 (62.3) |

59 (62.8) |

22 (62.9) |

0.992 |

16 (66.7) |

43 (61.4) |

0.647 |

|

Heart Failure |

16 (12.3) |

11 (11.7) |

5 (14.3) |

0.765 |

2 (8.3) |

9 (12.9) |

0.723 |

|

Coronary Artery Disease |

23 (17.7) |

14 (14.9) |

9 (25.7) |

0.153 |

4 (16.7) |

10 (14.3) |

0.749 |

|

Myocardial Infarction |

7 (5.4) |

2 (2.1) |

5 (14.3) |

0.016 |

1 (4.2) |

1 (1.4) |

0.448 |

|

Atrial Fibrillation |

8 (6.2) |

4 (4.2) |

4 (11.4) |

0.210 |

0 |

4 (5.6) |

0.569 |

|

Cerebrovascular Accident |

7 (5.4) |

5 (5.3) |

2 (5.7) |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

Thromboembolic History |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Deep Vein Thrombosis |

5 (3.9) |

4 (4.2) |

1 (2.9) |

1.000 |

1 (4.2) |

3 (4.2) |

1.000 |

|

Pulmonary Embolism |

3 (2.3) |

3 (3.2) |

0 |

0.563 |

0 |

3 (4.2) |

0.569 |

|

Malignancy |

12 (9.2) |

7 (7.4) |

5 (14.3) |

0.303 |

1 (4.2) |

6 (8.5) |

0.675 |

|

Coagulopathic Disorder |

3 (2.3) |

2 (2.1) |

1 (2.9) |

1.000 |

1 (4.2) |

1 (1.4) |

0.443 |

|

Smoking History |

25 (19.2) |

16 (16.8) |

9 (25.7) |

0.255 |

3 (12.5) |

13 (18.3) |

0.754 |

|

Chronic Kidney Disease |

14 (10.8) |

7 (7.5) |

7 (20) |

0.056 |

2 (8.3) |

5 (7.1) |

1.000 |

|

End Stage Renal Disease requiring Dialysis |

2 (1.5) |

2 (2.1) |

0 |

1.000 |

2 (8.3) |

0 |

0.063 |

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of critically Ill patients with COVID-19

Abbreviations: TAC, therapeutic anticoagulation; PAC, prophylactic anticoagulation; IQR, interquartile range; ICU, intensive care unit; COPD, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

a Race and ethnicity data were collected by self-report

b Comorbidities listed were medical diagnoses included in the medical history defined by ICD-10 coding

The most common comorbidities among COVID-19 ICU patients were hypertension (62.3%), obesity (50%), and diabetes (43.1%). Comorbidities were similar between the TAC and PAC patients; however, more PAC patients had a history of myocardial infarction (14.3% vs 2.1%, p=0.016) and chronic kidney disease was more prevalent among PAC patients (20% vs 7.5%, p=0.056).

Admission vital signs, laboratory values, and diagnostic studies were similar between the two groups (Table 2); however, TAC patients had a higher median heart rate compared to the PAC group (101 beats per minute [IQR 28] vs 94 [IQR 27], p=0.016). These patients also trended toward a higher temperature compared to PAC patients (100.3 degrees Fahrenheit [IQR 3.1] vs 99.2 [IQR 3.8]; p=0.072).

|

|

All COVID-19 ICU Patients (n=130) |

Among All Patients |

Among TAC Patients |

||||

|

All TAC (n=95) |

PAC |

p value |

TAC Prehospital and In hospital (n=24) |

TAC In Hospital Only (n=71) |

p value |

||

|

Admission Vital Signs |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Temperature, median (IQR), degrees Fahrenheit |

100.1 (3.5) |

100.3 (3.1) |

99.2 (3.8) |

0.072 |

100.2 (2.7) |

100.3 (3.7) |

0.911 |

|

Heart Rate, beats per minute |

99 (25) |

101 (28) |

94 (27) |

0.016 |

94 (27) |

94 (29) |

0.119 |

|

Systolic Blood Pressure, mmHg |

130 (31) |

131 (31) |

128 (40) |

0.707 |

131 (24) |

130 (35) |

1.000 |

|

Initial O2 Saturation |

90 (12) |

90 (12) |

88 (12) |

0.808 |

92 (10) |

90 (13) |

0.355 |

|

Admission Laboratory Results |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

White Blood Cell Count, x109/L |

7.7 (5.9) |

7.6 (5.7) |

8.6 (6.5) |

0.889 |

7.2 (6.9) |

7.9 (5.5) |

0.841 |

|

Creatinine, mg/dL |

1.0 (0.7) |

1.0 (0.5) |

1.1 (1.1) |

0.159 |

0.9 (0.5) |

1.0 (0.6) |

0.469 |

|

Hemoglobin, g/dL |

13.2 (2.7) |

13.2 (2.5) |

13.2 (4.1) |

0.385 |

13.7 (2.3) |

13.1 (2.6) |

0.197 |

|

Platelets, x109/L |

214 (122) |

221 (115) |

188 (108) |

0.239 |

221 (142) |

222 (102) |

0.785 |

|

International Normalized Ratio, sec |

1.0 (0.1) |

1.0 (0.1) |

1.0 (0.1) |

0.737 |

1.0 (0.1) |

1.0 (0.2) |

0.606 |

|

Prothrombin Time, sec |

10.9 (1.5) |

11 (1.5) |

10.8 (1.2) |

0.350 |

10.9 (1.4) |

11 (1.5) |

0.673 |

|

Diagnostic Studies |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bilateral Infiltrates on Admission Chest X-ray, n (%) |

112 (86.2) |

81 (85.3) |

31 (88.6) |

0.628 |

20 (83.3) |

61 (85.9) |

0.746 |

|

Highest Value During Hospitalization |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lactate Dehydrogenase, U/L |

548 (322) |

576 (319) |

498 (235) |

0.112 |

532 (304) |

618 (343) |

0.067 |

|

Ferritin, ng/mL |

1140 (1375) |

1132 (1432) |

1153 (1324) |

0.801 |

1039 (1245) |

1171 (1741) |

0.711 |

|

D-Dimer, mg/L |

4.3 (12.1) |

4.3 (12.8) |

4.1 (5.9) |

0.850 |

3.0 (9.8) |

4.4 (16.1) |

0.248 |

|

Fibrinogen, mg/dL |

634 (256) |

634 (312) |

634 (150) |

0.683 |

613 (403) |

636 (314) |

0.517 |

|

Lowest P/F Ratio |

74 (60) |

73 (51) |

78 (93) |

0.415 |

65 (73) |

74 (41) |

0.834 |

Table 2 Admission vital signs and laboratory results of Critically Ill patients with COVID-19

Abbreviations: TAC, therapeutic anticoagulation; PAC, prophylactic anticoagulation; IQR, interquartile range; PF, arterial oxygen partial pressure to fractional inspired oxygen

Patients in both the TAC and PAC groups were critically ill. 94.6% of all COVID-19 ICU patients were diagnosed with ARDS, 68.5% with severe ARDS. Mechanical ventilation was required in 110 patients, 78 (82.1%) TAC patients vs 32 (91.4%) PAC patients (p=0.191). The majority of patients had shock requiring vasopressors during ICU admission (74.6%) (Table 3). Concomitant bacterial pneumonia was significantly higher in TAC patients (44.7% vs 22.9%; p=0.024); however, there was no difference in other infectious complications between the two groups.

|

|

All COVID-19 ICU Patients (n=130) |

Among All Patients |

Among TAC Patients |

||||

|

All TAC (n=95) |

PAC (n=35) |

p value |

TAC Prehospital and In hospital (n=24) |

TAC In Hospital Only (n=71) |

p value |

||

|

ARDS |

123 (94.6) |

90 (94.7) |

33 (94.3) |

1.000 |

22 (91.7) |

68 (95.8) |

0.598 |

|

Mild ARDS |

6 (4.6) |

4 (4.3) |

2 (5.7) |

0.662 |

1 (4.4) |

3 (4.2) |

1.000 |

|

Moderate ARDS |

30 (23.1) |

22 (23.4) |

8 (22.9) |

0.948 |

7 (30.4) |

15 (21.1) |

0.360 |

|

Severe ARDS |

89 (68.5) |

66 (70.2) |

23 (65.7) |

0.623 |

14 (60.9) |

52 (73.2) |

0.260 |

|

Vasopressor Requirement |

97 (74.6) |

71 (76.3) |

26 (74.3) |

0.809 |

9 (39.1) |

62 (88.6) |

<0.001 |

|

Infectious Complications |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bacterial Pneumonia |

50 (38.5) |

42 (44.7) |

8 (22.9) |

0.024 |

8 (33.3) |

34 (48.6) |

0.195 |

|

Urinary Tract Infection |

26 (20.0) |

20 (21.1) |

6 (17.1) |

0.621 |

3 (12.5) |

17 (23.9) |

0.235 |

|

Bacteremia |

28 (21.5) |

21 (22.1) |

7 (20.0) |

0.798 |

2 (8.3) |

19 (26.8) |

0.060 |

|

Acute Kidney Injury |

82 (63.1) |

59 (62.8) |

23 (65.7) |

0.757 |

9 (39.1) |

50 (70.4) |

0.007 |

|

Kidney Replacement Therapy |

31 (23.9) |

26 (27.4) |

5 (14.3) |

0.120 |

3 (12.5) |

23 (32.4) |

0.059 |

|

Acute Hepatic Injury |

9 (6.9) |

7 (7.4) |

2 (5.7) |

1.000 |

0 |

7 (9.9) |

0.185 |

|

Cardiac Complications |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Arrhythmia |

35 (26.9) |

26 (27.4) |

9 (25.7) |

0.850 |

4 (16.7) |

22 (31.0) |

0.174 |

|

Myocardial Infarction |

4 (3.1) |

3 (3.2) |

1 (2.9) |

1.000 |

0 |

3 (4.2) |

0.569 |

|

Cardiomyopathy |

8 (6.2) |

4 (4.2) |

4 (11.4) |

0.210 |

0 |

4 (5.6) |

0.569 |

|

Venous Thromboembolism |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) |

3 (2.3) |

2 (2.1) |

1 (2.9) |

1.000 |

1 (4.2) |

1 (1.4) |

0.443 |

|

Days to DVT, median (IQR) |

19 (10) |

15.5 (7) |

22 (0) |

|

19 (0) |

12 (0) |

|

|

Pulmonary Embolism (PE) |

3 (2.3) |

3 (3.2) |

0 |

0.561 |

1 (4.2) |

2 (2.9) |

1.000 |

|

Days to PE, median (IQR) |

3 (5) |

3 (5) |

-- |

|

5 (0) |

1.5 (3.0) |

|

|

Ischemic Cerebrovascular Accident |

3 (2.3) |

3 (3.2) |

0 |

0.562 |

1 (4.2) |

2 (2.9) |

1.000 |

|

Hemorrhagic complications |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Intracranial Hemorrhage (ICH) |

2 (1.5) |

2 (2.1) |

0 |

1.000 |

1 (4.2) |

1 (1.4) |

0.443 |

|

Gastrointestinal Bleed (GIB) |

6 (4.6) |

5 (5.3) |

1 (2.9) |

1.000 |

1 (4.2) |

4 (5.6) |

1.000 |

Table 3 Treatments provided and complications of Critically Ill patients with COVID-19

Thrombotic complications

There was no difference in DVT or PE rates between the TAC and PAC groups (Table 3). Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) occurred in two patients in the TAC group and one patient in the PAC group (2.1% vs 2.9%; p=1.000). However, only one of the two patients with DVTs in the TAC group was on therapeutic anticoagulation at the time of DVT diagnosis and had subtherapeutic anticoagulation laboratory levels. Pulmonary embolism (PE) occurred in three patients, all of whom were in the TAC group, however only one patient was on therapeutic anticoagulation at the time of diagnosis. These TAC patients that were not on TAC at the time of VTE diagnosis were either admitted just prior to the initiation of the TAC protocol or developed VTE after discharge from the ICU and completion of the TAC protocol. Three patients had ischemic cerebrovascular accidents (CVA), all of whom were in the TAC group.

Hemorrhagic complications

There was no significant difference in gastrointestinal bleeds (GIB) or intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) between the two groups (Table 3). Hemorrhagic complications were observed in eight patients during their hospital course, seven of whom were in the TAC group. Two patients (2.1%) in the TAC group experienced ICH while receiving therapy; zero patients in the PAC group had ICH. One ICH patient died and one recovered and was discharged to a rehabilitation facility. Neither patient was supratherapeutic on anticoagulation at the time ICH was diagnosed. GIB occurred in five patients (5.3%) in the TAC group and one patient (2.9%) in the PAC group. Two of the five GIB patients in the TAC group died, although death was not due to hemorrhage shock. The remainder were discharged to rehab.

Anticoagulation as related to mortality:

The overall mortality was 50.8% for COVID-19 ICU patients, with hospital length of stay greater among survivors (21 days [IQR 18.5] vs 12 [9]; p<0.001). There was a trend toward lower mortality in the TAC group on univariate analysis (46.3% vs 62.9%; p=0.094). ICU length of stay (13 days [IQR 14] vs 6 [5]; p<0.001), hospital length of stay (17 days [15] vs 12 [9]; p<0.001), and ventilator days were greater among TAC patients (13 days [IQR 13] vs 5.5 [4.5]; p<0.001) (Table 4).

|

|

All COVID-19 ICU Patients (n=130) |

Among All Patients |

Among TAC Patients |

||||

|

All TAC (n=95) |

PAC (n=35) |

p value |

TAC Prehospital and In hospital (n=24) |

TAC In Hospital Only(n=71) |

p value |

||

|

Invasive Mechanical Ventilation, n (%) |

110 (84.6) |

78 (82.1) |

32 (91.4) |

0.191 |

14 (58.3) |

64 (90.1) |

0.001 |

|

IMV on admission |

38 (29.2) |

25 (32.1) |

13 (40.6) |

0.390 |

6 (42.9) |

19 (29.7) |

0.358 |

|

Hospital days prior to IMV, median (IQR) |

3 (2) |

3 (2) |

3 (4) |

0.990 |

4 (2.5) |

3 (2) |

0.391 |

|

Ventilator Days |

9.5 (10) |

13 (13) |

5.5 (4.5) |

<0.001 |

12 (9) |

13 (13) |

0.549 |

|

ICU Length of Stay (days) |

9 (12) |

13 (14) |

6 (5) |

<0.001 |

7.5 (12) |

14 (14) |

0.044 |

|

Hospital Length of Stay (days) |

16 (14) |

17 (15) |

12 (9.0) |

<0.001 |

23 (15.5) |

17 (15) |

0.200 |

|

Mortality, n (%) |

66 (50.8) |

44 (46.3) |

22 (62.9) |

0.094 |

1 (4.2) |

43 (60.6) |

<0.001 |

|

Discharge Disposition |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rehab |

25 (19.2) |

20 (21.3) |

5 (14.3) |

0.640 |

8 (33.3) |

12 (17.1) |

<0.001 |

|

Skilled Nursing Facility |

5 (3.9) |

4 (4.3) |

1 (2.9) |

|

1 (4.2) |

3 (4.3) |

|

|

Long Term Care Facility |

2 (1.5) |

2 (2.1) |

0 |

|

0 |

2 (2.9) |

|

|

Home |

41 (23.9) |

24 (25.5) |

7 (20.0) |

|

14 (58.3) |

10 (14.3) |

|

|

Discharged on Home Oxygen |

15 (11.5) |

12 (23.1) |

3 (21.1) |

1.000 |

5 (21.7) |

7 (24.1) |

0.838 |

|

30 Day Readmission |

7 (5.4) |

6 (35.3) |

1 (50) |

1.000 |

1 (20.0) |

5 (41.7) |

0.600 |

Table 4 Outcomes for critically Ill patients with COVID-19

Abbreviations: TAC, therapeutic anticoagulation; PAC, prophylactic anticoagulation; IMV, invasive mechanical ventilation; IQR, interquartile range

Twenty-seven patients were chronically anticoagulated prior to hospitalization. 24 of whom remained on TAC throughout their admission and therefore received prehospital and in hospital TAC. Of those 24 patients, only 1 died resulting in a 4.2% mortality rate, as compared to a mortality rate of 60.6% in those who received in hospital only TAC and 62.9% in those who received PAC (p<0.001) (Table 4, Figure 2). Of the 3 patients who were anticoagulated prehospital and were not therapeutically anticoagulated during hospitalization, 1 died. Higher survival probability was observed among prehospital and in hospital TAC patients compared to in hospital only TAC patients and PAC patients (Figure 3).

Figure 2 Mortality rates among COVID-19 ICU patients depicting lowest mortality among patients who were anticoagulated prehospital and in hospital compared to those who were only anticoagulated during hospitalization only or who received prophylactic anticoagulation.

Figure 3 Kaplan-Meier survival curve depicting a higher survival probability among critically ill COVID-19 patients who were treated with therapeutic anticoagulation before and during their hospitalization as compared to patients who received therapeutic anticoagulation only during hospitalization or who received prophylactic anticoagulation.

Prehospital and in hospital TAC patients compared to in hospital only TAC patients

When comparing characteristics and comorbidities of patients who received prehospital and in hospital TAC compared to those who received in hospital only TAC, there was no statistically significant difference (Table 1). When comparing admission vital signs and laboratory results among these two groups, there was no difference (Table 2). When comparing complications between these groups, there was no difference in ARDS, bacterial pneumonia, cardiac, thrombotic, or hemorrhagic complications among the two groups (Table 3). More patients who received in hospital only TAC required vasopressors for shock [9 (39. 1%) vs 62 (88.6%), p<0.001] and had acute kidney injury [9 (39.1%) vs 50 (70.4%), p=0.002]. Although not statistically significant, more in hospital only TAC patients had bacteremia [2 (8.3%) vs 19 (26.8%), p=0.060].

Less prehospital and in hospital TAC patients required mechanical ventilation compared to in hospital only TAC patients [14 (58.3%) vs 64 (90.1%), p<0.001]. Of the patients who were mechanically ventilated, there was no difference in the number of ventilator days [12 (IQR 9) vs 13 (13), p=0.354] between these groups. ICU length of stay was less in the prehospital and in hospital TAC group compared to the in hospital only TAC group [7.5 (IQR 12) vs 14 (14), p=0.044]. Hospital length of stay was not different (Table 4).

Multivariable analysis

In multivariable analysis, patients treated with prehospital and in hospital TAC had 92% lower risk of death (RR=0.08, 95% CI: 0.01-0.51, p=0.008) than patients treated with PAC when adjusted for age, sex, race, and severe ARDS (Table 5). Patients who received in hospital only TAC had a similar risk of mortality as compared to PAC patients (RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.69-1.24, p=0.621).

|

|

Mortality |

Model 1 RR (95% CI) |

Model 2 RR (95% CI) p-value |

Model 3 RR (95% CI) p-value |

Model 4 RR (95% CI) p-value |

Model 5 RR (95% CI) |

|

TAC Prehospital and In Hospital |

4.2 |

0.07 (0.01, 0.46) 0.006 |

0.08 (0.01, 0.52) 0.009 |

0.07 (0.01, 0.51) 0.008 |

0.10 (0.02, 0.66) 0.017 |

0.08 (0.01, 0.51) 0.008 |

|

TAC in Hospital Only |

60.6 |

0.96 (0.70, 1.32) 0.818 |

1.02 (0.76, 1.38) 0.880 |

0.97 (0.7, 1.33) 0.837 |

1.00 (0.74, 1.35) 0.992 |

0.93 (0.69, 1.24) 0.621 |

|

PAC |

62.9 |

Reference |

Reference |

Reference |

Reference |

Reference |

|

Age, per one year |

|

-- |

1.01 (1.00, 1.03) 0.037 |

1.02 (1.00, 1.03) 0.035 |

1.02 (1.00, 1.04) 0.013 |

1.02 (1.00, 1.03) 0.012 |

|

Sex |

|

-- |

|

|

|

|

|

Male |

57.5 |

|

1.56 (1.06, 2.29) 0.025 |

1.53 (1.04, 2.25) 0.03 |

1.52 (1.03, 2.22) 0.033 |

1.50 (1.03, 2.17) 0.033 |

|

Female |

37.2 |

|

Reference |

Reference |

Reference |

Reference |

|

Race |

|

-- |

-- |

|

|

|

|

Caucasian |

52.5 |

|

|

Reference |

Reference |

Reference |

|

Hispanic |

53.5 |

|

|

1.21 (0.81, 1.80) 0.349 |

1.16 (0.80, 1.68) 0.425 |

1.13 (0.78, 1.64) 0.506 |

|

Black |

41.2 |

|

|

0.92 (0.55, 1.54) 0.746 |

0.82 (0.50, 1.37) 0.457 |

0.88 (0.58, 1.36) 0.574 |

|

Asian |

45.5 |

|

|

1.01 (0.67, 1.51) 0.970 |

0.96 (0.68, 1.36) 0.823 |

0.99 (0.66, 1.47) 0.950 |

|

Mechanical Ventilation |

|

-- |

-- |

-- |

|

-- |

|

Yes |

|

|

|

|

3.87 (1.12, 13.4) 0.033 |

|

|

Severe ARDS |

|

-- |

-- |

-- |

-- |

|

|

Yes |

62.9 |

|

|

|

|

2.35 (1.41, 3.90) 0.001 |

Table 5 Multivariable modified poisson regression analysis of critically Ill patients with COVID-19

Abbreviations: TAC, therapeutic anticoagulation; PAC, prophylactic anticoagulation; RR, Risk Ratio; CI, Confidence Interval; ARDS, Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome

Mortality was associated with age such that for every additional year of age, the risk of death increased by 3% (RR=1.03, 95% CI: 1.01-1.04, p=0.002). The risk of death was higher for males (RR 1.50, 95% CI: 1.03-2.17, p=0.033). Patients with severe ARDS experienced nearly a 2.4-fold increased risk of death relative compared to patients without severe ARDS when adjusting for TAC, age, sex and race.

This retrospective review of a natural observational cohort study of COVID-19 ICU patients did not reveal a difference in mortality when comparing those treated with TAC vs PAC (Table 4). However, in comparison to patients who received in hospital only TAC or PAC, those who received TAC before and during hospitalization had a 12-fold lower risk of death (p=0.008). Mortality among patients who received prehospital and in hospital TAC was 4.2% compared to 60.6% in patients who received in hospital only TAC and 62.9% in patients who received PAC (p<0.001). This is the first study to our knowledge that demonstrates lower mortality among COVID-19 patients with prehospital anticoagulation therapy.

When comparing patients who received prehospital and in hospital TAC to those who received in hospital only TAC, there was no difference in initial baseline characteristics, comorbidities, initial vital signs, or laboratory values on admission. However, of those that had continued anticoagulation prehospital and in hospital, fewer had bacteremia and acute kidney injury, and fewer required vasopressors. While one possible explanation is this population was less sick, there was no difference in severe ARDS, yet less prehospital and in hospital TAC patients required intubation compared to those who received in hospital only TAC. We hypothesize that this finding along with the mortality benefit is secondary to a protective effect from continued anticoagulation.

Recent literature describes COVID-19 induced coagulopathy with increased VTE rates despite PAC, PE rates of 16-35% in mechanically ventilated COVID-19 patients, and cumulative VTE complication rates of up to 87%.10,22,23 This rate is substantially greater than the described 2.77% thromboprophylaxis failure rate in randomized controlled trials among acutely ill non-COVID-19 patients.24,25 In our study, there was a 2.3% rate of PE, 2.3% rate of DVT, and 2.3% rate of CVA among critically ill COVID-19 patients. We did not perform routine screening diagnostic imaging to evaluate for VTE in COVID-19 ICU patients which may account for our overall low VTE complication rate as compared to recent literature, however this may also be attributable to a protective effect from TAC. Our overall low 8.4% VTE complication rate among the 95 TAC patients, suggest the anticoagulation dosages used in this protocol may improve COVID-19 related morbidity.

Historically, there is a small, accepted rate of hemorrhagic complications when using TAC in order to achieve a larger benefit across the greater population; however, anticoagulation is not without risk and usage needs to be individualized to each patient. Only eight patients (6.1%) had hemorrhagic complications, seven of whom were in the TAC group. Five of these patients had mild GIBs and two TAC patients had ICH, one of whom died. While initial emerging single center studies showed the risk of VTE in COVID-19 patients was higher than the risk of significant bleeding events,24,25 and COVID-19 patients treated with therapeutic anticoagulation had decreased rates of mortality compared to patients not systemically anticoagulated,21,22 larger more recent randomized controlled trials are not as clear.26-30 As we had one death secondary to an ICH and did not see an overall benefit in mortality to patients who received in hospital only TAC, we do not advocate for the blanket usage of TAC among all COVID-19 ICU patients but recommend an individualized approach instead.

There are several ongoing randomized controlled trials in hospitalized COVID-19 patients to best evaluate the benefits and harms of anticoagulation.26-30 There are currently three platforms aligned enrolling hospitalized COVID-19 patients in a large international randomized controlled trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04372589) evaluating whether full dose anticoagulation reduces mortality and days free of organ support.30 While this study has yet to be completed, the National Institute of Health released two statements, the first that the trial paused enrollment of critically ill COVID-19 patients as therapeutic anticoagulation did not reduce the need for organ support and a potential harm in this subgroup could not be excluded.31 Conversely, their second statement reported a trend in the reduction of mortality and decreased need for organ support in moderately ill COVID-19 patients, defined as patients not admitted to the ICU without mechanical ventilation requirements.32 Importantly, patients who require anticoagulation for other medical indications are excluded from enrollment in this randomized controlled trial.

These early reports match our findings that critically ill patients who received in hospital only TAC did not have a mortality benefit as compared to PAC patients. However, as our study is the first to demonstrate patients anticoagulated before and during hospitalization have a reduced mortality with a 92% lower risk of death, this subset of patients who receive anticoagulation for indications other than COVID-19 are excluded from the ongoing randomized controlled trial emphasizing our trial’s findings and the need for further studies to examine this patient population.

This was a single center study, limited by its observational nature, with a relatively small population, not designed for randomization or intervention. As our center was among the first affected by the pandemic in the United States, clinical practice patterns changed over the course of this study as new literature emerged related to COVID-19. This potentially introduced confounding bias regarding other therapies provided such as IL-6 inhibitors, antivirals, steroids and convalescent plasma. Further studies including patients who received prehospital anticoagulation are needed to truly determine whether therapeutic anticoagulation before and during hospitalization confers a survival benefit to critically ill COVID-19 patients.

In this observational cohort study of critically ill COVID-19 patients admitted to an ICU, there was a significantly lower risk of mortality among patients treated with therapeutic anticoagulation prior to and during hospitalization compared to those treated with in hospital only therapeutic anticoagulation or those treated with prophylactic anticoagulation. We believe systemic anticoagulation has a protective effect on critically ill COVID-19 patients who receive prehospital anticoagulation. As these patients have been excluded from ongoing randomized controlled trials, further studies including this patient population are needed to determine the mortality benefit and risk profile of TAC.

To the best of our knowledge, no personal conflict of interest exists. There are no other disclosures. All authors have made substantial contributions to all of the following (1) the conception and design of the manuscript, or acquisition of data, or interpretation of data/dilemma, (2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, (3) final approval of the version to be submitted.

None.

©2021 Choron, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

World Tuberculosis Day (March 24) provides the opportunity to raise awareness about TB-related

problems and solutions and to support worldwide TB-control efforts. While great strides have been made to control and cure TB, people

still get sick and die from this disease in our country. On this event, we request researchers to spread more information and awareness

on this by their article submissions towards our JLPRR. For this we are rendering 25% partial waiver for articles submitted on or before

March 24th.

World Tuberculosis Day (March 24) provides the opportunity to raise awareness about TB-related

problems and solutions and to support worldwide TB-control efforts. While great strides have been made to control and cure TB, people

still get sick and die from this disease in our country. On this event, we request researchers to spread more information and awareness

on this by their article submissions towards our JLPRR. For this we are rendering 25% partial waiver for articles submitted on or before

March 24th.