Journal of

eISSN: 2376-0060

Research Article Volume 4 Issue 6

1Health Information, Communication and Research Bureau, Provincial Health Division, Democratic Republic of the Congo

2Department of Pediatrics, University of Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo

3Higher Institute of Medical Techniques, Democratic Republic of the Congo

4Measure Evaluation, Democratic Republic of the Congo

5Department of Public Health, University of Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo

Correspondence: Olivier Mukuku, Department of Pediatrics, University of Lubumbashi, Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo

Received: October 14, 2017 | Published: December 22, 2017

Citation: Bafwafwa DN, Mukuku O, MbuliLukamba R, Tshikamba EM, Kanteng GW, et al. (2017) Risk Factors Affecting Mortality in Children with Pulmonary Tuberculosis in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo. J Lung Pulm Respir Res 4(6): 00151. DOI: 10.15406/jlprr.2017.04.00151

Introduction: Childhood tuberculosis remains poorly understood and presents diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. The objective of this study was to describe the epidemiological, diagnostic and therapeutic aspects of childhood pulmonary tuberculosis in Lubumbashi in the DRC and to identify risk factors for mortality.

Methods: This is a retrospective analytical study of the medical records of children (under 15 years of age) followed for pulmonary tuberculosis at the 22 centers’ tuberculosis Diagnostic and Treatment during the period 1 January 2013 to 31 December 2015 in Lubumbashi.

Results: 717 cases of pulmonary TB had been recorded during the study period. 377 were males and 340 were females. The mean age was 8.3 years (range: 6 months-14 years). The evolution was known for 674 children of whom 157 died (mortality rate 23.3%). In multivariate analysis, age ≤5 years (aOR=7.03 [4.36-11.35]), emaciation (aOR=2.95 [1.82-4.78]), HIV seropositivity (aOR=5.25 [3.20-8.62]), negativity by direct microscopy (aOR=2.04 [1.13-3.68]) and leukocytes ≥12000/mm3 (aOR=1.99 [1.28-3.09]) are independent predictors of mortality.

Conclusion: TB is still a very severe disease with high mortality rates in children. Early recognition of infection associated with correct early treatment, systematic entourage investigation and chemoprophylaxis by isoniazide in all children under 5 years of age is essential for attempting to reduce these prognostic indices.

Keywords: pulmonary, tuberculosis, national tuberculosis program, primary health care, acid-fast bacilli

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a major public health problem in the world and particularly in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). The recent World Health Organization (WHO) annual report estimated that 10.4 million new cases (incidents) of tuberculosis worldwide occurred, of which 61% of all cases were in Asia and 26% in Africa.1 Pulmonary form accounted for more than 80% of the cases diagnosed. The DRC is among the 22 countries in the world most affected by TB; it occupies the eleventh place in the world and the third in Africa.1 The DRC has reported 119,000 cases of all forms of TB in 2015. Tuberculosis accounts for 10% of all reported TB cases. According to the WHO report, the annual incidence of tuberculosis in children is estimated at 1 million, with 170,000 deaths in 2015.1 Tuberculosis in children remains poorly understood and a diagnostic challenge and therapeutic. This disease has a double impact on children: it is a major cause of mortality due to the rapid development of severe forms and is a source of precariousness in the health and social life of children following the death of their parents.2,3 In countries where TB is endemic, very few studies have been conducted on child mortality risk factors during TB treatment. Mortality of tuberculous children during TB treatment varies from one study to another. Rates of 3.3% in Ethiopia, 6% in Thailand and 8.3% in Burkina Faso; in these populations, a combination of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and malnutrition was associated with death.4–6 For this reason, we conducted this study to describe the socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB) patients, to determine the hospital mortality rate and to identify the factors associated with these deaths.

Context and population of the study

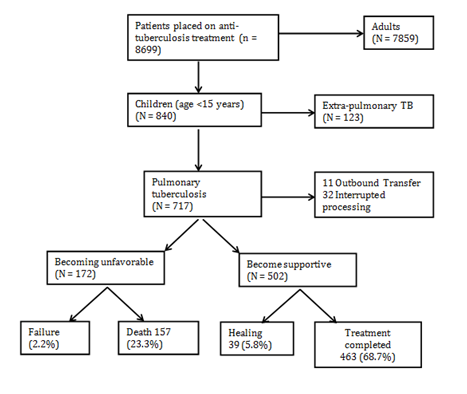

In the DRC, the fight against TB is the task entrusted to the National Tuberculosis Program (NTP), it is part of the direction of the fight against the diseases. In order to achieve its various objectives, the NTP recommends an integrated approach to TB control activities in Primary Health Care (PHC) structures in line with the strategy for strengthening the health system. The structure that provides diagnosis and treatment for tuberculosis patients is called the Diagnostic and Treatment Center (CSDT). The CSDT is the functional unit of the NTP. It is equipped with diagnostic tools (a microscope with immersion lens, rapid diagnostic tests, etc.) endorsed by the WHO, but also equipped with a trained staff. A sample of its smears is also regularly checked by the higher level according to the national strategy in this area. Some CSDTs are equipped with XPERT MTB/Rif machines depending on their strategic location and the number of suspected multi-resistant (MR) cases in the vicinity. Screening and treatment are free. The drug supply and other inputs to tuberculosis control are subsidized.7 We conducted a cross-sectional retrospective study. Our team collected data from the 22 CSDTs in Lubumbashi, the capital of the Haut-Katanga Province in the DRC. The target patients were children under 15 years of age admitted to the CSDT with a diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis between the 1st January 2013 and 31 December 2015. In total, 717 patients were treated (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Written and verbal informed consent was taken from the Medical Ethics Committee of the University of Lubumbashi, DRC.

Definitions of cases

The diagnosis of smear-positive TBP was made if a patient met at least one of the following criteria:7

The diagnosis of smear-negative TBP was made if the patient met the following criteria:7

AFB negative in three sputum samples,

At the end of treatment, the fate of the patient is recorded in one of the following mutually exclusive categories:7,8

Cured: patient whose sputum examination is negative during the last month of treatment and at least on a previous occasion;

In TBSCs, all TB children are screened for HIV infection after obtaining informed consent from their parents. We also included patients who were unable to produce appropriate sputum specimens but whose symptoms and clinical history were consistent with active TB. Patients with both PBD and extra pulmonary tuberculosis have been classified as TBP in accordance with the definition of the World Health Organization.9

Data collection and analysis

Demographic and clinical information was collected from medical records using a standardized data collection form. The following data were extracted from the records of each patient: age, sex, contagion with a known TB case, history of TB, presence or absence of BCG vaccine scar, and time to onset of symptoms before admission to the service. The following general and physical clinical signs were systematically recorded: asthenia, weight loss, anorexia, unexplained fever (≥15 days) greater than or equal to 38°C, persistent cough (≥15 days) and peripheral lymphadenopathy. The results of the direct tuberculosis bacillus test, as well as those of the hemogram and HIV serology of each patient at admission were also recorded and recorded. The fate of each child at the end of treatment was noted. Children who were cured and those who had completed treatment were classified as having successful treatment (or having a favorable outcome).10,11 Fate was rated unfavorable in the event of failure or death (Figure 1). The data were entered into an electronic database using Microsoft Excel 2013. The risk of death during TB treatment was measured. Patient characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics. For the investigation of risk factors for death, we used logistic regression models to produce adjusted odds ratios (ORa) and their 95% confidence intervals. The variables were introduced into the multiple logistic regression model when their p-value was <0.2 according to a downward step-down selection method. The level of statistical significance was set at 5%. All statistical analyzes were performed using Stata software version 12.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA).

Socio-demographic, clinical and paraclinical characteristics

During the target period, a total of 717 children were followed for a diagnosis of PTB. Table 1 presents the socio-demographic, clinical and paraclinical characteristics of the 717 patients included. The median age of patients was 9 years (range 6 months and 14 years); more than 52% of them were male or a sex ratio of 1.1. The absence of vaccination with BCG was found in 13.1% of cases and the notion of tuberculous infection in 70.7% of cases. Nearly 7 out of 10 patients were treated with nonspecific antibiotics prior to initiation of TB treatment. Previous anti tuberculosis treatment was present in 1.8% (13/717) of patients. Among all patients, ≥15 days was the most common symptom (72.1%), followed by asthenia (66.8%), anorexia (65.8%), persistent cough ≥15 days (64.0%) and weight loss (61.2%). The median duration of symptoms from inception to admission was 17 days (range from a few hours to 37 days). The positivity of intradermal reaction was noted in 452 patients (63%) and HIV serology in 139 patients (19.4%). In 28% (201/717) of cases, confirmation was given for direct microscopic examination of sputum. Confirmed cases increased significantly with age (p<0.0001).

Variable |

Frequency (n=717) |

Pourcent |

|

Age |

≤5 years |

172 |

24 |

6-9 years |

229 |

31.9 |

|

≥10 years |

316 |

44.1 |

|

Average |

100.3± 47.6 |

||

Sex |

Male |

377 |

52.6 |

Female |

340 |

47.4 |

|

Family Tuberculosis |

Present |

507 |

70.7 |

Absent |

210 |

29.3 |

|

BCG vaccine scar |

Present |

623 |

86.9 |

Absent |

94 |

13.1 |

|

Non-specific antibiotics |

1 antibiotic |

187 |

26.1 |

≥2 antibiotics |

307 |

42.8 |

|

No antibiotics |

223 |

31.1 |

|

Anterior tuberculosis treatment |

Yes |

13 |

1.8 |

No |

704 |

98.2 |

|

Emaciation |

Present |

439 |

61.2 |

Absent |

278 |

38.8 |

|

Peripheral lymphadenopathy |

Present |

293 |

40.9 |

Absent |

424 |

59.1 |

|

Anorexia |

Present |

472 |

65.8 |

Absent |

245 |

34.2 |

|

Asthenia |

Present |

479 |

66.8 |

Absent |

238 |

33.2 |

|

Cough |

Present |

459 |

64 |

Absent |

258 |

35.9 |

|

Fever |

Present |

517 |

72.1 |

Absent |

200 |

27.9 |

|

Intradermal test |

Positive |

452 |

63 |

Negative |

265 |

37 |

|

Leukocytes |

<12000/mm3 |

237 |

33 |

≥12000/mm3 |

480 |

67 |

|

Direct microscopy |

Positive |

201 |

28 |

Negative |

516 |

72 |

|

HIV serology |

Negative |

578 |

80.6 |

Positive |

139 |

19.4 |

|

Table 1 Sociodemographic, Clinical and Paraclinical Characteristics of 717 Children with TBP

Risk factors for mortality

Of the 674 children whose progression is known, 157 died during treatment, which corresponds to a mortality rate of 23.3% (Figure 1). Table 2 shows the factors associated with mortality. Univariate analysis showed an association with higher mortality in elderly patients (age ≤5 years), in patients previously treated with TB, in the case of weight loss, peripheral lymphadenopathy, (≥12 000/mm3), direct microscopy negativity and HIV seropositivity. Multivariate analysis revealed that age ≤5 years (aOR= 6.95 [4.33-11.15]), weight loss (aOR=2.86 [1.77-4.60]), HIV seropositivity (aOR=4.93 [3.03-8.01]), direct microscopy negativity (aOR=1.86 [1.04-3.32]) and leukocytosis ≥12000/mm3 (aOR=1.99 [1.29-3.06]) were most closely associated with mortality during tuberculosis treatment in children.

Variable |

Death (n=157) |

Survival (n=517) |

Univariate analysis crude OR [IC95%] |

Multivariate analysis adjusted OR [IC95%] |

Age ≤5 ans |

84 (53.5) |

75 (14.5) |

6.78 [4.55-10.09] |

6.95 [4.33-11.15] |

Males and Females |

89 (56.7) |

266 (51.5) |

1.23 [0.86-1.77] |

- |

Family Tuberculosis |

104 (66.2) |

368 (71.2) |

0.79 [0.54-1.16] |

- |

BCG vaccine scar absent |

26 (16.6) |

62 (12.0) |

1.45 [0.88-2.39] |

0.70 [0.39-1.27] |

No non-specific antibiotics |

52 (33.1) |

154 (29.8) |

1.17 [0.79-1.71] |

- |

Anterior tuberculosis treatment |

8 (5.1) |

4 (0.8) |

6.88 [2.04-23.18] |

2.48 [0.64-9.47] |

Slimming present |

118 (75.2) |

292 (56.5) |

2.33 [1.56-3.48] |

2.86 [1.77-4.60] |

Peripheral lymphadenopathy present |

75 (47.8) |

198 (38.3) |

1.47 [1.02-2.11] |

1.48 [0.97-2.28] |

Anorexia presents |

104 (66.2) |

337 (65.2) |

1.05 [0.72-1.53] |

- |

Asthenia presents |

99 (63.1) |

349 (67.5) |

0.82 [0.56-1.19] |

- |

Persistent cough |

97 (61.8) |

336 (65.0) |

0.87 [0.60-1.25] |

- |

Unexplained fever |

110 (70.1) |

374 (72.3) |

0.89 [0.60-1.32] |

- |

Intradermo-positive reaction |

92 (58.6) |

332 (64.2) |

0.80 [0.55-1.14] |

- |

Leukocytes≥12000/mm3 |

71 (45.2) |

154 (29.8) |

1.95 [1.35-2.81] |

1.99 [1.29-3.06] |

Negative direct microscopy |

136 (86.6) |

345 (66.7) |

3.23 [1.96-5.29] |

1.86 [1.04-3.32] |

Positive HIV Serology |

61 (38.9) |

67 (13.0) |

4.27 [2.83-6.44] |

4.93 [3.03-8.01] |

Table 2 Risk factors for death in children with pulmonary tuberculosis in Lubumbashi

The hospital mortality rate among TBP children in the city of Lubumbashi reached a rate of 23.3%. This mortality in this study is higher than that reported previously in other African countries where TB is endemic: 3.3 to 5.8% in Ethiopia,4,12–14 7.3% in Senegal,15 9% in Benin,16 10.5% in Botswana,17 and 10.9% in Tanzania18 and 17% in Malawi.19 Lower rates were also reported in Asia: 1.1%20 in India and 6% in Thailand.5 This high mortality in our study could be attributed to late diagnosis and delayed treatment. These reported death rates in all of these studies may be underestimated due to the lack of data on the out-of-pace and out-of-pupil outcomes. A number of factors associated with death have been reported. The mortality rate among children under 5 years of age was significantly higher than that of those over 5 years of age (aOR=6.95 [4.33-11.15]). Our results corroborate those of the studies conducted by Hailu in Ethiopia,4 Salarri in Iran,21 and Wu in China.22 In line with this finding, a study in Malawi revealed a fall in death rates with older age.19 Younger children, especially those younger than 2 years of age, are at increased risk of death from infectious diseases, including tuberculosis due to the immaturity of the immune system. In addition, disseminated tuberculosis and tuberculous meningitis, associated with high mortality, are more common in young children.23–25 The diagnosis of tuberculosis in younger children remains challenging and most of them end up with anti-tuberculosis treatment without confirmation. This leads to a delay in the diagnosis and treatment of other serious diseases, especially opportunistic HIV-related infections, leading to increased mortality.4

In many of our patients (61.2%), we observed a significant loss of weight and a correlation between mortality and weight loss (aOR=2.86 [1.77-4.60]). Previous studies have suggested that a low BMI and a lower concentration of serum albumin are important risk factors for mortality in tuberculosis patients.26–28 It can be assumed that malnutrition would be a clinical finding reflecting the severity of pulmonary tuberculosis and that the determinant of intra-hospital mortality is due to the severity of pulmonary tuberculosis rather than to malnutrition itself. Wen's study showed that underweight was associated with a 10-fold increase in tuberculosis mortality.29 TB-HIV co-infection was 19.4%. Knowledge of the HIV status of HIV is essential for better management of TB and HIV infection. Nearly half of all HIV-infected children with tuberculosis died during the treatment of tuberculosis. In this study, co-infection with HIV was found to be an independent predictor of death (aOR = 4.93 [3.03-8.01]) and this is consistent with previous studies elsewhere.4,17,28,30 Lolekha found that HIV-infected tuberculous children were 6.9 times more likely to die than those who were HIV-negative (aOR=6.9 [1.4-33.0]).5 HIV contributes substantially to burden of childhood tuberculosis. HIV co-infection is commonly associated with multiple infections that complicate diagnosis and treatment, leading to greater morbidity and mortality.4 In this study, negativity of direct microscopy (smear negative) was associated with death (aOR=1.86 [1.04-3.32]).As in our study, some studies12,18,20 reported that smear-positive TBP was associated with favorable treatment outcomes. Contrary to our findings, Hailu4 and Bloss31 found that children with smear-positive PTB died more than smear-negative children and assumed that it was related to the advanced stage of tuberculosis in which the majority of patients in their series.

Limitations of the study

This study is not without limits and therefore the results of this study should be interpreted in the light of the following limitations. Our study has certain limitations related to its retrospective nature. First, socio-economic data, including family income and the educational status of parents that may influence the outcome of treatment, have not been documented and therefore the role of these variables has not been studied. In addition, some potential risk factors for mortality, including co-morbidities, were not recorded sufficiently in the medical records and chest x-rays were not available. We did not have data on the treatment of patients transferred and transferred under treatment. Failure to include them in our calculation could lead to some bias in the analysis of risk factors for mortality. This study has limitations in its lack of data for patient compliance in taking medications. It is possible that a patient may take anti-tuberculosis drugs appropriately as recommended.

TB is still very severe with high mortality rates in children. Knowledge of these risk factors for death during the treatment of TB should enable specific actions to be taken to improve the survival of these patients. Early recognition of infection associated with correct early treatment, systematic investigation and chemoprophylaxis by isoniazid in all children under 5 years of age is essential for attempting to reduce these prognostic indices.

All authors carried out the conceptualization, design, data collection and analysis for the study, contributed to the interpretation of the findings and the drafting of the article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

©2017 Bafwafwa, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

World Tuberculosis Day (March 24) provides the opportunity to raise awareness about TB-related

problems and solutions and to support worldwide TB-control efforts. While great strides have been made to control and cure TB, people

still get sick and die from this disease in our country. On this event, we request researchers to spread more information and awareness

on this by their article submissions towards our JLPRR. For this we are rendering 25% partial waiver for articles submitted on or before

March 24th.

World Tuberculosis Day (March 24) provides the opportunity to raise awareness about TB-related

problems and solutions and to support worldwide TB-control efforts. While great strides have been made to control and cure TB, people

still get sick and die from this disease in our country. On this event, we request researchers to spread more information and awareness

on this by their article submissions towards our JLPRR. For this we are rendering 25% partial waiver for articles submitted on or before

March 24th.