Journal of

eISSN: 2376-0060

Mini Review Volume 3 Issue 5

Department of Pulmonary Diseases, Germany

Correspondence: Askin Gulsen, Department of Pulmonary Diseases, Westkstenklinikum Heide, Germany, Tel +90 545 5969708

Received: August 17, 2016 | Published: September 24, 2016

Citation: Gulsen A. Intrathoracic gossypiboma: 2 case reports and review of the literature. J Lung Pulm Respir Res. 2016;3(5):144–148. DOI: 10.15406/jlprr.2016.03.00100

Intrathoracic gossypiboma (IG) is a sponge inadvertently left in the thoracic cavity during surgery, also referred to as a retained surgical sponge, textiloma, gauzoma, muslinoma or cottonoid. Although gossypibomas are most frequently reported after abdominal surgery, they are occasionally associated with cardiac or pulmonary surgery. Although the actual incidence of IG is not precisely known, its estimated incidence is 1 case per 1,000–10,000 surgeries. Here we report two cases of IG treated in our hospital along with a systematic review of the current literature. The literature review revealed that patients can be misdiagnosed with ailments such as aspergilloma, bronchial carcinoma, bronchiectasis, hydatid cyst, and empyema. The average time from the initial surgery to diagnosis is 6.9yr (range, 3 wk to 52yr). The patient often presents with asymptomatic complaints such as cough, pain, vomiting or fever in the early postoperative period. Cases with a history of intrathoracic surgery should be assessed for possible IG in differential diagnosis of new masses. To avoid morbidity, it is very important that sponges used during operations be counted carefully and that radiopaque sponges be used.

Keywords: gossypiboma, intrathoracic surgery, differential diagnosis, retained sponge, complication

Intrathoracic gossypiboma (IG) is a sponge inadvertently left in the thoracic cavity during surgery,1 also referred to as a retained surgical sponge/swap, gauzoma, muslinoma, textiloma, or cottonoid. Although gossypibomas are most frequently reported after abdominal surgery, they are occasionally associated with cardiac or pulmonary surgery. IGs lead to serious surgical complications and are considered medical errors; thus, they are likely under-reported for medicolegal reasons.2 Although the actual incidence of IG is not precisely known, its estimated incidence is 1 case per 1,000–10,000 surgeries.3 A review of PubMed identified about 20 cases of IG worldwide. A systematic review of the literature on IG revealed that patients can be misdiagnosed with ailments such as hematoma,4 bronchiectasis,5 bronchial carcinoma,6 aspergilloma,7,8 and hydatid cyst.9,10 In some cases with cystic cavities, gossypiboma can be diagnosed immediately after the biopsy.11,12 The patient often presents with asymptomatic complaints such as cough, pain, vomiting or fever in the early postoperative period. The average time to diagnosis is 6.9yr,13 but can be as long as 52yr following surgery.11 Acute presentations typically involve a septic reaction with abscess or granuloma formation. Delayed presentation may also result in an adhesion or encapsulation.14

The first case presented here was selected to emphasize the importance of considering IG in differential diagnosis of patients following diagnoses of lung abscess and empyema. The second case is presented because there were no complaints over a long period of time.

Case 1: A 47-year-old male patient was admitted to our clinic with fever, cough, dyspnea, right flank pain and yellow-green sputum that had continued for 14days. He had a significant past medical history of coronary artery disease and mitral stenosis, as well as a history of tobacco use. A pacemaker (PM) had been implanted in the right side of his chest in 2002. The patient had been admitted to a cardiology clinic in February 2004 with a diagnosis of PM-lead infective endocarditis, and the PM was removed. A mitral valve commissurotomy via a right mini-thoracotomy had been performed in 2005.

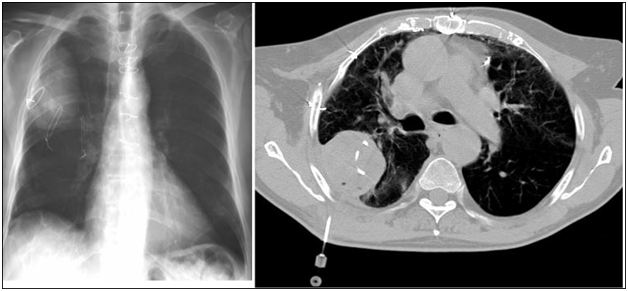

On physical examination, his temperature was 38.5°C, his pulse was 60bpm, his respiratory rate was 16breaths/min, his blood pressure was 135/80mmHg, and his oxygen saturation was 97% on room air. His white blood cell (WBC) count at the time of admission was 15,600/µL. In his respiratory system examination, dullness was detected on percussion in the right middle zone. His auscultation and other system examinations proved normal. A chest X-ray showed a 6cm mass in the right middle zone (Figure 1). A computerized tomography (CT) scan of the thorax showed a 6x8cm2 homogeneous soft tissue mass in the right hemithorax adjacent to the pleura, suggesting a diagnosis of empyema or lung abscess.

Figure 1 Posteroanterior chest X-ray (a) and CT of the thorax (b) showed a 6x8 cm2 homogeneous soft tissue mass in the right hemithorax adjacent to the pleura.

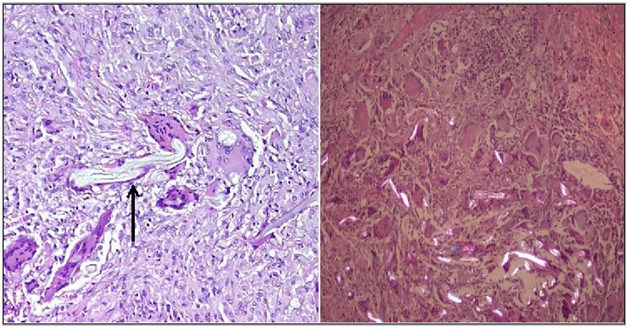

We obtained purulent material with therapeutic thoracentesis. The pH of the fluid was 7.29 and the bacterial culture result was negative. The patient underwent a CT-guided, fine-needle aspiration (CT-FNA) and a catheter was inserted into the pleural space by interventional radiology (Figure 2). Pus was aspirated from the catheter each day and irrigation was performed with normal saline. An indirect hemagglutination assay for a hydatid cyst proved negative. We began a carbapenem and aminoglycoside combination for a lung abscess and empyema diagnosis. The pus became liquid following the treatment and radiological regression was observed in the first week. Despite 2wk of therapy, there was radiological progression and a debridement with video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery was carried out. The macroscopic appearance of the outer surface of the surgically removed material was irregular and grayish-brown. Once a surface section was removed, grayish-yellow and grayish-white areas and sutures were also observed. Microscopic observations included suture sections in fatty and fibrous connective tissue areas and a foreign body reaction consisting of foreign body giant cells, histiocytes and mononuclear cells (Figure 2). The diagnosis was a foreign body tissue reaction (IG). The characteristic appearance of the material suggested a sponge left behind during a past operation in the thorax. One month later a chest X-ray showed that the radio density had adequately regressed (Figure 3).

Figure 2 Microscopic observations included suture sections in fatty and fibrous connective tissue areas and a foreign body reaction consisting of foreign body giant cells, histiocytes and mononuclear cells.

Case 2: A 67-year-old male patient receiving long-term, regular treatment due to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was admitted to our clinic with complaints of shortness of breath for 1wk, phlegm, and sweating. He had a smoking history of 20packs/yr. A coronary artery bypass graft had been performed in 2005 and a left anterior descending coronary artery stent implanted in 2007. Although a mass was detected in the left lung and surgery had been recommended, he had not consented to surgery.

Physical examination revealed a fever of 38.3°C and diminished breathing sounds in the respiratory system examination. Other systemic examinations were normal. His WBC was 11,000/µL, sedimentation was 44/h, and C-reactive protein was 2.41mg/dL. Pulmonary function test findings were forced expiratory volume 1 (FEV1) of 1.64L 50% and FEV1/forced vital capacity (FVC) of 54%. Following these tests, the patient was started on clarithromycin and theophylline due to exacerbation of COPD. In the initial posteroanterior chest X-ray on admission, a 4-cm well-circumscribed mass was observed in the upper left zone. CT of the thorax showed a 4x5cm2 mass in the left upper lobe adjacent to the pleura. Suture materials were observed inside the mass (Figure 4). A possible IG was diagnosed and surgery was recommended. However, the patient did not consent and a follow-up period was begun.

Gossypiboma is a foreign body reaction against the cotton matrix in a sponge and formation of a radiologically observable mass.1 Based on the literature, the average time from the initial surgery to diagnosis is 6.9yr (range, 3wk to 52yr).11,13 Time to diagnosis was 5-9years in our cases. In our clinic, patients with IG commonly present with complaints varying from chronic cough to shortness of breath, chest pain, fever and weight loss. Some cases, such as Case 2 presented here, may be asymptomatic for several years. Radiologic findings can be misdiagnosed as hematoma,4 bronchiectasis,5 malignancy,6 aspergilloma,7,8 hydatid cyst,9,10 and empyema (Table 1).

Author |

Operation History |

Time to Diagnosis |

Complaints |

Tentative Diagnosis |

Coskun M et al. [4] |

Mitral valve operation |

3 week |

* |

Hematoma |

Suwatanapongched et al. [5] |

Left under lobectomy |

22 years |

Chronic Cough |

Bronchiectasis |

Garcia et al. [6] |

Pneumothorax operation |

23 years |

Sputum Dyspnea |

Bronchial carcinoma |

Park et al. [7] |

Right middle lobectomy |

31 years |

Hemoptysis |

Aspergilloma |

Mir et al. [8] |

Right upper lobectomy |

9 years |

Cough |

Aspergilloma |

Vara C et al. [9] |

Left under lobectomy |

37 years |

Chest pain |

Hydatid cyst |

Patel et al. [10] |

Mitral valve repair surgery |

18 years |

Hemoptysis |

Hydatid cyst |

Parra M et al. [11] |

Lung Bilobectomy |

52 years |

Hemoptysis Chest Pain |

Gossypiboma |

Sologashwili et al. [12] |

Tricuspid valve repair |

11 years |

Asymptomatic |

Gossypiboma |

Case-1 |

Mitral valve repair surgery |

5 years |

Sputum Right flank pain |

Empyema |

Case-2 |

CABG |

9 years |

Asymptomatic |

Gossypiboma |

*: no information |

||||

Table 1 Initial complaints, the operation history, time to diagnosis and tentative diagnosis of the cases diagnosed with intrathoracic gossypiboma in the literature

Gossypibomas are most frequently observed in the abdomen (56%) and less frequently in the pelvis (18%) or thorax (11%).15 Gossypibomas are reported to occur more frequently after emergency abdominal surgeries and in obese patients.3 Obesity increases the technical difficulty of an operation, and a large body cavity can result in the loss of a sponge or instrument. More involvement of staff experienced in emergency surgery may reduce this risk.

Although radiological findings may vary, well-circumscribed soft tissue density or calcification can be observed in chest X-rays. CT is the preferred tool for diagnosing IGs.16 The CT aspect may differ by location and factors such as a high-attenuating mass, air bubbles, and granulomas. Spongiform patterns are characteristic of abdominal and intrathoracic gossypibomas.17 These findings may be misdiagnosed as empyema or abscess. Air crescent signs5,7 or cystic cavities.11,12 Can be observed in some cases.

Ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging can also be used for diagnosis.18,19 Observing suture samples in the ultrasound or foreign body reactions in ultrasound-guided FNA material can be helpful for diagnosis. Treatment of IG is surgical excision.20 In the USA, hospitalizations due to lost medical objects cost more than $60,000 per patient and related malpractice suits may cost $150,000–500,000 per case.21 Thus, prevention should be emphasized.

Patients with a history of intrathoracic operation should be assessed for IG in differential diagnosis of new masses. To avoid morbidity, it is very important that sponges used during operations be counted carefully and that radiopaque sponges be used.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

None.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

©2016 Gulsen. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.