Journal of

eISSN: 2573-2897

Research Article Volume 3 Issue 2

Universidad del Rosario, Colombia

Correspondence: Ruben Dario Serrato, Universidad del Rosario, Colombia, Tel 52 1667 2659 504

Received: August 26, 2017 | Published: April 20, 2018

Citation: Serrato RD. The weapons of money: financing and administration mechanisms in the second expedition of pedro de cevallos to the rio de la plata, 1777. J His Arch & Anthropol Sci. 2018;3(2):205-2017. DOI: 10.15406/jhaas.2018.03.00097

By the end of 1776, about 4,000 soldiers belonging to the Portuguese crown threatened the Spanish territories of the Rio de la Plata. In response, King Carlos III ordered the organization and shipment to America of the largest expedition, in terms of resources, which had been seen so far. On November 13 of this year, one hundred and sixteen ships (31 frigates, 2 frigates (urcas), 22 brigantines, 41 frigates (saetias) and 20 frigates of the King) carrying a total of 9,038 men, more than 2,000 pieces of artillery and an amount close to the 800,000 pesos to 8 reales in money,1 left from the ports of Cadiz to the control of the general Pedro de Cevallos, under the protection of 632 cannons.2 The objectives were precise to defend the dominions of the king before the Portuguese threat and to organize administratively the territories adjacent to the zone, (especially the port of Buenos Aires later turned into vice regal capital). In order to carry out such a large company, it was necessary a whole machinery of maintenance, financing, organization and logistics that guarantee its success. This research seeks to make an analysis of the logics of financing and economic administration of the second expedition of Pedro de Cevallos that would arrive to America in 1777,3 investigating the way in which this event energized the local market, being one of the clearest examples of direct injection of own money of the crown to America; To finally answer how the American reality can fit within a new theoretical methodological proposal the fiscal-military state.1−3

Keywords: economic history, fiscal-military states, Spain empire, war, buenos aires, xviii century

1The official account of the troops and the cargo is in the General Archive of the Nation of Argentina, (hereinafter AGN) IX, 4-3-8.

2AGN, IX, 1-1-3.

3By 1757, the Spanish crown decides to send about 1,000 armed men to the command of the newly appointed Lieutenant General of His Majesty's Armies, Pedro de Cevallos. The purpose of this first expedition would be to contain the Guarani indigenous rebellions directly supported by the members of the Society of Jesus (jesuitas). By november 1757, the date of that expedition's arrival, the rebellion had been subdued and limited to gathering and transferring approximately 15,000 Indians to the new villages to be built on the right Riviera of the Uruguay River. To enlarge, see: Albino (2005).

Much is the ink that has run in analyzing the composition of public expenditure of the reign of Carlos III, since it has been understood by historiography as a period of modernization, at least in its objectives and therefore a stage of change that would serve to explain the peninsular and overseas realities that would come in the later years. The reign of Carlos III was mainly concerned with responding to the objectives of expanding its territories, properly managing them and maintaining an effective market policy, elements of a colonial power as the 18th century Spanish monarchy attempted to be. However, it did not have an economic balance that allowed him to solve all his needs as an empire, giving a significant priority to some and forgetting others, equally relevant. 4 The previous perspective has been widely accepted by authors such as Jacques Barbier & Herbert Klein,4 who endeavored to study the complexity of the finances of the Old Regime and specifically fiscal policy from 1760 to 1778.4 According to these, the analysis of this period allows us to understand the intentions and aims of the crown that appear in the data of expenses and distribution of funds in the different areas that were handled at the time. From a series of quantitative methods, Barbier & Klein4 argue that war expenditures increased unmanageably for the crown. 5 The maintenance of the armies was too high for the empire and did not entail a production of resources that could solve this expense. This difficulty increased the increasing dependence on semiofficial entities that supplied resources to the Spanish crown, which would take the same very close to the ruin. The maintenance of the wars of this period and the payment of those that had previously occurred drastically limited the economic capacity of the crown, which would be tied up to direct these resources to new enterprises, evidently affecting the subsequent government of Carlos IV. According to these authors, the priority of the Empire of Carlos III was mainly the maintenance of the imperial war.6 The investment of enormous sums of resources in the navy and the military limited in a considerable way the capacity of the monarch to distribute its funds in companies of greater profitability and efficiency for its coffers that constituted a productive investment for its own ends.7

This inclination of the monarchy towards war, the presence of the military in civil administration and the increase of the budget in defense, even greater than the levels seen during the Habsburg era, are for John Lynch characteristics of the undisputed military dimension of the Bourbon state.8 In the same historiographical line, Josep Fontana, says that for the monarch it was always more important to invest his resources in military spending, leaving aside the construction of a series of modernizing reforms that allowed a strengthening and sustaining of the mercantile economy.9 This perspective has prevailed in some historiographical analyzes, even in recent authors and until some years ago there had been no further discussion. Following Vicent Llombart can be described as the historiographic current "fiscalist-warmonger". However, some Hispanists such as Rafael Torres Sánchez, Agustín González Enciso and José Jurado Sánchez, specialists in the eighteenth century, have begun to question the bases of this argument and especially the idea that economic development is disconnected from military activity or it has a negative influence. They affirm that it is necessary to make a contemporary interpretation of historical reality, detached from any anachronistic critique.10 Similarly, they insist on the possibility of questioning the idea of "warlike priority" that is said to have existed in the empire of Carlos III.

The ideal of these new Hispanist authors is based on returning to the sources of finance, through new statistical and quantitative analysis, to have a deeper and objective knowledge of this historical reality. This proposal has a novel character: comparative history.11 Thinking about the similarities and differences between the processes of different latitudes, without establishing a hierarchy between them, helps not only to understand one's own development, but also the general development of them. The process of comparing the British Empire with its Spanish counterpart, allowed these Hispanists to review the commonplace that "fiscalist-warmongering" historiography had accepted as analytical paradigms. A new methodological proposal was generated that has understood these processes of investment in the military as representatives of a "fiscal-military" state.

4Barbier y Klein H. (1985), 473-495.

5Barbier y Klein H. (1985), 491.

6Lombart (1994), 11-39.

7A controversial investment, since, from certain points of view, it has been considered as an obligation that had the Spanish crown and not an end in itself. For Agustín González Enciso, for example, Carlos III made such an exponential expenditure because it was strictly necessary and inescapable and was not seen as a means to increase his wealth and territorial influence. For this reason, the case of the Spanish monarchy becomes an example far from the fiscal-military states, since what characterizes these states is precisely military investment as a sure guarantee of economic, political and territorial growth. This discussion is proposed in: González Enciso (2008).

8Lynch (1991), 274.

9Fontana (1971), 20-29.

10Jurado Sánchez (2006); Torres Sánchez (2013).

11“En su gran résumé leído al Congreso Internacional de Estudios Históricos de 1928, Pour une histoire comparée des sociétés européennes, publicado más tarde en la «revue de Synthèse» de Berr, Marc Bloch definiría la historiografía comparativa como una varita mágica (baguette de sorcier) capaz de abrir nuevos campos de investigación y de formular nuevos juicios. Hasta hoy sin embargo, ha funcionado como método sólo en un sentido muy limitado: es más un procedimiento para plantearse preguntas.” Maier (1992-93), 11.

The concept of "fiscal-military state" originated from the study of the case of the British Empire and I consider it important to highlight this process. The first mention of the term is found in the text The Sinews of Power by historian John Brewer.5 The author presents an analytical picture to explain the case of the emergence of Great Britain as a colonial empire, consolidating itself as the power of greater power throughout the eighteenth century.12 The term "fiscal-military status" is defined as a category that seeks to explain how an adequate and efficient administrative apparatus, supported by an expansive fiscal and financial system, allowed Great Britain to maintain greater armed forces, win wars and eventually achieve an Imperial supremacy.

Lawrence Stone develops this category more broadly, claiming that it was indeed war that took the place of catalyst for growth and subsequent domination in the modern world by the British Empire.13 This dominion allowed England to expand the roads and commercial routes that would be the basis of a strong, abundant mercantilism and with capacity to be in constant expansion thanks to the military apparatus. By the seventeenth century, the English state remained relatively separate from major continental conflicts. Because of this, it managed to grow as a strong and unified state, maintaining a central political power that was characterized by having the military forces under direct orders of the parliament. As a result, according to the author, a socio-economic advantage was created compared to other European states such as France, Spain or Prussia who sought to strengthen their military power while attempting to unify and build as centralizing states, which is why they failed to deploy the whole of the weaponry as England would do during the eighteenth century. The British Empire managed to exert a dominion not only on its own colonies, but also, to face and to overcome to the empires that sought to rival its power.14

It is now necessary to define the principles of the fiscal-military state in order to understand its application. Although the resources are necessary to sustain a war, the mobilization of the same obeys to an order of political character. The state is the one who confronts and justifies measures to finance a war. For this reason, seeing the state in action at the moment to hold a conflict helps in understanding the nature of the state itself. For a fiscal-military state, the priority in military activity over any other kind of government function must be obvious. This priority is rooted in three fundamental objectives: the maintenance of an armed force capable of managing the production and collection of resources; To guarantee maneuverability within a confrontation at the international level, either as an invader or in defensive terms; And, finally, to ensure a continuous flow of resources to pay debts from previous wars. These objectives, within the state logic, have an important basis in the fiscal apparatus. The supreme argument of the fiscal increase was the demand for resources of the war.15

This domination over fiscal resources is not only coercive, as Charles Tilly said;16 besides has to do with the legitimacy of the state vis-à-vis society. War is then part of the discourse of legitimacy in the eyes of the population, since until the end of the eighteenth century the greatest source of this will be the capacity for protection. For this reason, war is not only the main function of the state but the main way to guarantee its own legitimacy.17 These are the patterns that follow states characterized as fiscal-military. This term has awakened a number of responses, both positive and negative and has prompted academics to be interested in this type of realities, as is the case of Javier Cuenca Esteban who analyzes the case of the state fiscal-military in India;18 Jan Glete the case of Sweden from 1650 to 1815;19 Helen Julia Paul makes a thorough analysis of African companies;20 and even cases are found as far back as the Far East, studied by Professor Toshiaki Tamaki, who makes a comparison of the fiscal-military state between Europe and Japan,21 to cite some examples. Undoubtedly, in the case of Hispano-American, Rafael Torres Sánchez has been one of the most influential researchers in international historiography. His study does not focus on detailing only the components of the Spanish state, but also bases its work on a quantitative analysis with lines of comparison between the economic-military reality of the Spanish Empire and the English Empire.22

The first thing is to understand the historical reality of each of the appropriate measures by the state of Carlos III to understand how it mobilized resources for war.23 It is crucial to analyze in greater depth the priorities of the Spanish state in the Bourbon reform era and to understand how these had an impact on the economy. Torres Sanchez shows us through a series of timelines how many were the years in which the Spanish Empire really maintained an armed conflict and, comparatively, how many in which the English Empire was involved in a war. These periods are divided as follows: from the Spanish war of succession from 1701 to 1713, until the War of the Austrian Succession from 1739 to 1748, there would be about 30 years of conflict for each Empire. However, with the Francoindian War (1754-1763), the Seven Years War (1756-1763) and the American War of Independence (1775-1783), Britain would face about 19 more years of open conflict than the monarchy Spanish. Military competition was based on economic and scientific growth and this growth fueled the "arms race" in which the colonial powers would have a dominant place almost independent of victories or defeats. As the time of conflict in the Spanish monarchy was less than in the British Empire, after the latter became a centralized state, the Spanish economy did not have a sufficiently propitious way to expand a strong trade and access to new territories that were a source of resources. Torres Sánchez shows that practically all the entrances of war of Carlos III had a defensive character. For the Spanish Empire, no major conflict was concentrated on obtaining new resources or territories but seeking to protect and organize what was already there. As evidenced by statistics and data on sources of finance, it can be verified that the Spanish monarch spent much less economic resources than his English counterpart. According to statistical tables, presented in the work of Torres Sánchez, between the years of 1759 to 1793, the monarchy of Carlos III spent 334,103 release of fleece in its armed forces, divided in 197,452 for the army and 136,651 in the navy. England, on the other hand, would spend in the same period a total of 813.051 release of fleece, divided in 365.809 in own expenses of the army on foot and 447.242 in the investment to the marine forces.24 In addition to these data, quite telling, since we triple the investment from one empire to another, we have the data on administrative expenditure, which was thought to have been reduced according to military spending.25 During these years, the Spanish empire spent in the administration field a total of 178,192 release of fleece, while the British would spend 126,788.26 We can see two central conclusions in this data: first, military spending is supremely short in the reign of Charles III compared to that of George III; The warlike priority did not exist and even this non-existence was one of the reasons why the economy did not grow to the levels where it would in the British Empire. In addition, administrative expenditure in the Spanish Empire was greater than that of the English empire and yet the latter was consolidated as a much stronger, powerful and politically important military, fiscal and military state,27 contradicting the premises of the first stream presented in this work -Barbier and Klein-.6−10

The question that arises when analyzing these data is who is right. Does war produce an increase or decrease in the economy? Was Carlos III's exaggerated military spending the cause of the decline of the Spanish Empire? Or, from the economic point of view, was it a mistake not to have caused more wars? I am of the opinion that the pacifist option, according to the conclusive data exposed by the authors, was not reasonable at this moment in history if one wanted to grow economically. In addition, the Spanish monarchy had numerous failures from the military fiscal field. Resources, from a strategic point of view, should have been conducted to a much higher extent than the navy and not the army on land. Great Britain knew of the need to control the seas and this would give it a decisive advantage not only during the eighteenth century but also created the scaffolding of naval power evident in the twentieth century world conflicts where it continued to be maintained as the fleet more powerful in the world, which avoided, among other causes, its fall in the Second World War. This structure was maintained throughout the centuries and the expense, or investment, was well led from the royal coffers to the imperial seas.

However, many historians and social scientists have sought to analyze the societies of the past through a dichotomous relationship between the militia and the development of the economy of society. The war has a structural character, based on the socioeconomic policy of each state, which speaks of a social complexity related to hierarchical divisions, alliances and own logics.28 It can be a window to understand the social behaviors of each type of community. War is a cultural construction, as Malinowski29 once put it and we have understood it well in this part of the world. To name an example among many others, Eder Gallegos analyzes, in the case of New Spain, how the military tools, strategic knowledge, the artillery economy and arms themselves are cultural products that are modified from a series of interests Premises of the region at the end of the 18th century.30 It is clear that the relationship between economy and war is evident in the history of empires and societies, as shown by the fiscal-military state; and these new projects can also help understand a structural operation that allowed not only defending against enemies and threats, but also to access new territories and ensure the continuous growth of each community.

Some other studies touch slightly on the relationship between the economy and the militia, such as the work of John TePaske A New World of Gold and Silver,31 which publishes the collection of figures of the tax collection of the Spanish empire in different populations American; Or, the study by Carlos Sempat Assadourian about the importance of the South American colonial internal market.32 Others like Ruggiero Romano,33 Jorge Gelman,34 Juan Carlos Garavaglia,35 Fernando Jumar,36 Pedro Pérez Herrero,37 among many others, are tangentially approaching the debate. However, none of them uses the depth or the concept, nor the methodological logics presented here. All have an important place in the advance of economic historiography, but they are developed in other areas somewhat removed from the relationship proposed by the logics of the fiscal-military state. There is a dangerous absence within the analysis exposed so far. The work undertaken to understand the nature of the military-military state has focused on peninsular realities and large-scale armed conflicts, such as Spain's participation in the American War of Independence in the second half of the eighteenth century. However, the role of America is relegated, almost nonexistent, in the management of the logic of that state. Being considered a colonial territory, one among many others, do not take into account the processes of negotiation that existed between the peninsular and Hispano-Creole actors of the continent.

It is important to think adequately about the role of America since it does not comply with the colonial logics that proclaim the economic tradition of the nineteenth century, since the proceeds return as an investment to the American regions, in terms of political negotiation managed by different foci of power.38 America, for the eighteenth century, knows its geopolitical importance, so it must be understood as a fundamental actor in the process of building and consolidating the Spanish state. There we find an advantage that allows new researchers to enter into academic dialogue and contribute to the construction of this new explanatory model. It is now necessary to analyze the realities of the American continent, its conflicts, its participation in international wars, on a small and large scale, both to understand the way in which local interests and the peninsular were engaged in dialogue and to understand the way in which America Is established in this new model of the fiscal-military state.

In the previous historiographical balance a series of theses and approaches were presented that foment the debate in relation to determine if the Spanish Imperium of Carlos III can be or not considered a "fiscal-military State", in order to understand the reality of this in the context of reforms that, as historiography has shown, failed to achieve the stated objectives. I do not intend to make a definitive proposal, but to see how new interpretations can be formulated through the systematic study of economic sources such as letters accounts, purchase receipts and commercial orders; At the same time that we rethink the role that America played in this development. It is important to clarify that it is not a question of demonstrating that war, from a moral and ethical point of view, is positive. In this study, I sought to understand how states faced the need to be at war and how this position affected their economic development. It is evident that any individual who knows a little of the ferocity of war in the history of mankind knows the terrible tragedies and dantean images that are lived day after day in a conflict. As academics, we do not seek to judge these actions, we seek to describe, analyze and understand them, all within their context and analyzing case by case. Let's travel back in time to one of these.

12Brewer (1989).

13Stone (1994).

14Stone (1994).

15The principles of the Fiscal-Military State are presented in a more developed way in Torres Sánchez (2008).

16Tilly (1992).

17It is clear that the type of discourse on legitimacy was based on other areas of society as in discourses of collective imaginaries, imagined communities and religious character guaranteeing a membership. The fiscal-military state does not deny its importance, but does affirm that the war was consolidated as the best mechanism to guarantee such legitimacy. Expand in: Torres Sánchez (2008).

18Cuenca Esteban (2007).

19Glete (2007).

20Paul (2007).

21Tamaki (2007).

22One of his texts evidences this study: González Enciso (2008).

23Torres Sánchez (2013) busca responder a estos interrogantes.

24Torres Sánchez (2008), 419.

25Barbier y Klein (1985).

26Torres Sánchez (2008).

27Torres Sánchez (2008), 422.

28There are many authors who have supported this theory, coming from various areas such as the French anthropologist and ethnologist Pierre Clastres (2004) to the socioeconomic history of Anales, with Georges Duby (1988).

29"Humans never fight on a large scale under the direct influence of an aggressive impulse. They fight and organized for this because of the tribal tradition, the teachings of a religious system or aggressive patriotism, since they have learned certain cultural values that are prepared to defend, and are saturated with certain collective hatreds that make them ready to Assault and kill ... As a type of behavior can be diverted to an indefinite number of cultural motives.” Malinowski (1941), 132.

30Gallegos Ruiz (2011).

31In this study, the author is dedicated to verifying rather accurately the circulation flows of metals in certain particular regions of the continent. TePaske (2010).

32Assadourian (1982).

33Romano (2004).

34Gelman (2012).

35Garavaglia (1983).

36Jumar (2012).

37Pérez Herrero (1992).

38Juan Carlos Garavaglia (2005) condenses a great part of the arguments about the debate of the colonial relation, the colonial question and the vision of these on the part of the politics and the economy. On the other hand, Fernando Jumar (2014).

“Los Portugueses se entendieron y formaron establecimientos en los terrenos de SM [Su Majestad] al Sur de Río Grande y fundaron varios pueblos a la costa opuesta particularmente después del año de 1736 por la facilidad de la navegación de dicho río y por el comercio que mantenían por él con el Janeyro y con la isla de Santa Catalina con que la posesión de la Villa de San pedro y la boca del Río que les impide el ingreso inutiliza sus ideas de extenderse y poner freno a su ambición por esta parte.”39

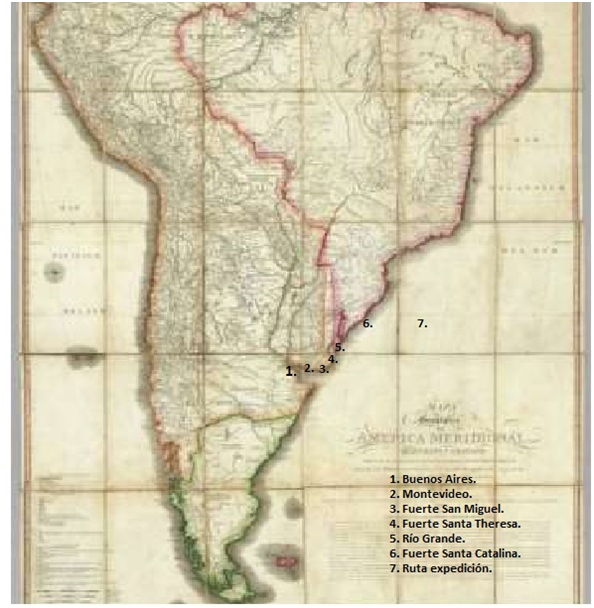

Bernardo de Alcalá, head of the government of Montevideo, would write the previous report in 1776 to describe the news and recent events that took place in territories bordering on the Portuguese empire of Jose I and later, Maria Francisca, its successor in 1777. The Portuguese expansion, although not very important, began to be a concern again for the Spanish Empire. The vestiges of the collective imagination of the conflicts brought to this part of the world by the Seven Years War (1756-1763) are still perceived in the 1770s. General Pedro de Cevallos already had experience in dealing with the Portuguese, since as governor of Buenos Aires he had mobilized his soldiers in defense of the Portuguese expansionist policy in 1757, waving the flag of the Spanish empire in the forts of San Miguel, Santa Theresa and Rio Grande, present federal state of Rio Grande do Sul of Brazil.40 These spaces would again be relevant to sustain the mercantile flow that would feed the second expedition of Pedro de Cevallos from Cadiz (Figure 1).41,10−15

Figure 1 Map of South America. This image is famous for the detailed Coasts and hydrography. It was a commission of the same Carlos III, in the Bourbon eagerness to collect information on the territory of which it was sovereign.

The fort of Santa Theresa, says of Alcalá, was reinforced by the considerable migration south of the Rio Grande. Growing trade with Rio de Janeiro increased production in the area, illegal commerce and increasing frequency in robberies of stables, cattle and offspring throughout the eastern margin of the Rio de la Plata. This situation of robbery and illegal trade in the Villa of San Pedro, next to the fort of San Miguel, increased the concern of the authorities, of Alcalá in Montevideo as well as of Juan Joseph de Vértiz, governor of Buenos Aires for 1776. San Pedro was distant 125 leagues from Montevideo and 165 from Buenos Aires, which made it imperative, in the words of Alcalá: "a competent garrison to keep for itself."42 The terrain was difficult and the Spanish authorities knew it. These fortifications: “están circundadas de construir así por el Río como por la sierra que llaman de los Tapes y por las lagunas que forman los derrames de aquél, por la que es preciso mucho número de tripa y un ramo de marina para la seguridad particularmente habiendo manifestado la experiencia se debe tener suma desconfianza del proceder de los portugueses a que se agrega la reflexión que estorbándoles esta posesión sus ideas es preciso que hagan esfuerzos para ocuparla.”43

For this reason, it is an area characterized by depopulation and zero cultivation. In order to carry out a military campaign for the area: “es preciso conducir los víveres de Buenos Aires cuyo transporte agrega un considerable gasto al Real Herario y ocasiona escases y crecidos precios en los mantenimientos, redundando de esto el disgusto y empeños de la guarnición. Habiéndose consumido los ganados desde dicha Villa de San Pedro al fuerte de Santa Theresa a excepción de unas cortas porciones para la subsistencia de las guarniciones de dicho fuerte y del de San Miguel se aumenta nuevamente el gasto de proveerlo de otra parte.”44 The concern of the Royal Treasury is not to maintain the ground to control its production, which is practically nonexistent, but because of the growing threat it would mean for the ports of the Rio de la Plata, which would soon fall again into Portuguese hands. The confrontation, then, began to be unavoidable, making visible the biggest problem that would have this military company: the maintenance and the direct flow of resources to feed it. At the end of the year 1776, a document that calls attention to its accuracy, with an unknown sender, was sent to the correspondence of Vértiz in Buenos Aires, which is intuitively sent by Alcalá due to the order of the documents in the General Archive. The governorate of Buenos Aires would have an estimate of the Portuguese forces that were ready to advance towards the south and the dominions of Carlos III, directly threatening the ports of exit of the Rio de la Plata and the entire surrounding commercial complex. He would find Alcalá on his desk the following information: "List of Portuguese forces: Infantry- 3216; Artillery- 200; Cavalry-400; Total: 3816.”45

39AGN, IX, 4-3-7.

40Barba (2009).

41“Geographic Map of South America, Arranged and Recorded by D. Juan de la Cruz Cano and Olmedilla, Geogfo. Pensdo. Of S.M. Individual of the Royal Academy of San Fernando, and gives the Basque Society of the Friends of the Country; Bearing in mind Various Maps and original news according to Astronomical Observations, Year 1775. London, Posted by William Faden, Geographer of the King, and Prince of Wales, January 1, 1799. "This image is famous for the detailed Coasts and hydrography. It was a commission of the same Carlos III, in the Bourbon eagerness to collect information on the territory of which it was sovereign. The present conventions were added at present to mark important points of location.

42AGN, IX, 4-3-7.

43AGN, IX, 4-3-7.

44AGN, IX, 4-3-7.

45AGN, IX, 4-3-8.

Under the shadow of this Portuguese threat, on November 13, 1776, the expedition consisted of the following: 20 King frigates, 31 frigates, 22 brigantines, 41 salutes and 2 merchant ships. These vessels carried more than 2,000 pieces of artillery of different calibres, 9,038 men ordered in 4 brigades of 16 battalions, real body of artillery, real body of engineers and the Staff of the expedition.46 Let's take a closer look at your crossing and the arrival to Santa Catalina Island. Following his departure from the ports of Cadiz, the expedition would see the island of Tenerife on November 20, 1776. This date would be the last time the convoy was seen united. By December 5 of that same year, more than 6 boats would be counted among the missing. In relation to the events, the commander of the fleet Francisco Tilly, would show his concern for the difficulty of the journey, the scorching heat that accompanied them and the growing problem of the disarticulation of the fleet: “The convoy daily was dismembered in a way That there were 24 separate boats, including the frigate Venus, brig Hopper and the two burlots and a few days later only 84 candles were incorporated.”47 On January 17, 1777, the convoy would arrive at the Island of Trinidad, to the northeast of Santa Catalina. At this meeting point, the generals, under Cevallos, decided to wait for the ships behind for 13 days. Similarly, 13 were the vessels that contacted the convoy, including the frigate Venus. Despite the absence of almost 2,000 troops, shortages of drinking water and little information collected from the territory where they were headed, the attack on the island of Santa Catalina was agreed for the day 29 of the same month. On that day the convoy sailed again, leaving the king's satire, Santa Ana, to gather the boats that could arrive in the next 7 days. Precisely, on February 6, luck would play in favor of the Spaniards. A small convoy of three Portuguese vessels was intercepted on its way from Rio de Janeiro to Lisbon. In addition to confiscating more than 86 thousand pesos in silver, a detailed listing of the state of squares of Brazil, in particular of Santa Catalina Island, was found. Tilly affirms, "With this light the generals walked with some knowledge and it was also known that the Portuguese were aware of the departure of our armament from Europe by a warning that arrived in Rio de Janeiro 37 days ago."48

On February 14, Don Pedro de Cevallos was recognized as Viceroy and Captain General of the provinces of the Rio de la Plata and it would be until the 20th, waiting for the most favorable conditions, that the navy captain would order the advance against the island. Those four o'clock in the afternoon would witness one of the quietest landings in marine history in connection with such a marine operation. No resistance was found. The northern zone, called Canaveiras, was landing place until the 23 of the same month. The following days were to recognize the territory, Cevallos ordering a caution with the central point of the island, where was a Portuguese castle that was thought empty. 150 riflemen under the command of Don Victorio de Navío marched to recognize the roads that led to the fortification, without immediate resistance. It would be at 3:30 in the morning that they would start the first shots against the Cevallos expedition. The castle fired two guns against the Septentrion, which was approaching on the east side of the fortification. Beginning a siege against the castle, Cevallos received a Portuguese artillery lieutenant who ran in the direction of the Spanish army, begging to be allowed to surrender, affirming the abandonment of the fortification. The Viceroy, a military expert, in the judgment of falling into a trap, prepared a group to inspect the castle and verify that information. On the afternoon of February 24, the fort was lined with the entire Spanish troop. For the 25th and 26th, the expedition concentrated on exploring the entire island in search of some sign of resistance. General Tilly would terminate the written relationship to his majesty as follows: “el día 27 toda la isla fue abandonada, y las armas de nuestro rey en pacífica posesión de ella, no habiendo costado, ni un solo tiro de fusil, sabiéndose por noticia, que la guarnición que tenía esta Isla se halla en la costa firme a distancia de 4 leguas experimentando las calamidades que trae consigo la guerra.”49

War is won with provisions. Cevallos was aware that with all the information he had about the Portuguese, he did not know exactly how long the conflict might last. He could not afford to skimp on economic efforts to supply the expeditionary force he commanded. If the objective is to secure the King's dominions, all political, social and economic forces must be moved to work on it. Let us see how the supply worked to supply the demands of the Viceroy.16−20

46AGN, IX, 4-3-8.

47AGN, IX, 4-5-1.

48AGN, IX, 4-4-1.

49AGN, IX, 4-5-1.

50It is a kind of unleavened bread, which delays its fermentation, allowing its storage for a longer time without risk to soon deterioration.

51AGN, IX, 4-5-1.

The economic circuit of the Rio de la Plata began to be the supply chain of the imperial army. In January of 1777, the preparations of sustenance of the expedition of Pedro de Cevallos begin to flourish. De Alcalá insisted on the urgent preparation of the salted meats and biscuit, peremptory for the adequate maintenance of the troop that is traveling across the Atlantic.52 Food is vital to the exercise of war. 40,000 bushels53 of wheat are ordered to be brought from nearby fields, sparing no logistical efforts. The ideal: that both parties, both the Royal Treasury, in charge of making the purchase, as the seller’s landlords had benefits. Alcalá affirms that wheat must be obtained "by paying its amount to cash and at the most moderate price, which at the same time, produce a profit to the Real treasury and offers profit to the landlords.”54

In America, the costs of expeditions, the characteristics of the climate, the geography and other local factors hindered the success of an invasion that did not have the best preparation and maintenance available at the time.55 Artillery had rendered the old medieval castles obsolete, turning the fortresses of the eighteenth century into important strongholds of resistance, which is why in most cases it was limited to establishing trenches around the besieged city or fortress and thus intimidating surrender. Military expeditions sought to minimize both human and material casualties because of the difficulty of replacing them on the American continent. The attack on a fortification then became a mathematical question, where food and supplies, both of the attacking side and the defender played the decisive role in the military contest.

The resources for supplying His Majesty's arms are in America and it is the Americans who will find the benefit of the sale of such merchandise. The document entitled "Wholesale status of foodstuffs that have embarked on the convoy of the command of Pedro de Cevallos to Santa Catalina",56 whose complete transcription to be part of the annexes of this writing, is a real account that specifies in what they were invested part of the resources that counted the expedition. These foods are destined to the island of Santa Catalina, where we saw previously was the post of arrival of the expedition and place that exerted as a center of operations, shelter and, specifically, supply. Important qualitative information, besides the quantitative data, that appears in the document is worth highlighting. All the resources presented here were bought in the markets of the city of Buenos Aires. About 10,370 quintals of food were sent by water and 3,844 quintals by land in 169 transport carts.57 The resources sent by water were transported in the same frigates that brought part of the soldiers sent by Carlos III. The expedition served as an opening of markets to local traders in the region. One might think that the navy sent from the peninsula not only functioned as a military expedition that sought to defend the sovereignty of the Spanish Empire in America but also was directly related to the economic growth of the city. As can be seen in the annex, there are various types of resources that were organized and sent by the local government and not restricted to only a part of the market, but covered and increased the production of various supplies and implements necessary for consumption.21−25

The documents give evidence of the royal orders in which the governor Pedro de Cevallos sends official delegates to the different points of production, storage, collection and transport of great resources, mainly sponge cake and salted meat. Each of the merchants and merchants who seek access to this new market for their products had to meet a number of requirements58 and approve the recognition given by the real delegates in the inspection visits.59 It is then an interesting administration strongly controlled by the local government, where the objective is to maintain the quality of the resources and to obtain the maximum profit of its production, main premise of the Spanish Bourbon governments of the time. The gears do not stop advancing. On March 27, 1777, a report presented to the local authorities was signed in Buenos Aires, stating that from Balisas, a port on the western side of the River, "there is no boat useful for transportation of food other than with Loads of flour and biscuits, with the exception of those conducting troops, or war supplies, because, according to the urgency of the matter, the Lord Lieutenant of King of this place.”60 The inspections of these provisions are meticulous and continuous: “Fernando Sánchez Sargento de la Cuarta compañía del 5 Batallón de Martina y Antonio Mendez contramaestre ambos de la dotación del Navío de Santo Domingo, Declaramos que mientras nuestra residencia en esta ciudad nos hemos empleado en recorrer las panaderías en donde se fabrica el bizcocho y las harinas que se embarcan para provisión de la Armada y hemos encontrado que todo es de muy buena calidad, y para que conste lo firman a nuestro ruego don Domingo Fernandez y Santiago Miguel en Buenos Aires a veinte y seis de marzo de mil setecientos setenta y siete.”61 The flour necessary for the feeding of the troop seems to be in good condition, both in its production and in its transport. It is a necessary resource that mobilizes money and energizes commerce. In addition, it seems to be the indicated resource for the maintenance of real strength, as it lends itself to easy transport and effective storage. Mateo Perzicos, one of the royal officers in charge of the collection and distribution of vivieres, states in Buenos Aires on March 7: “Muy Señor mío: No me dispensaré de fatiga para embarcar cuantas Harinas y bizcocho pueda en todas las lanchas útiles, que navegan en este río, como VS se sirve prevenirme en oficio de 4 del corriente mes, con motivo de las noticias dadas a VS por el Alferez de Navío de José de Salcedo. Todo el bizcocho fabricado útilmente es superior, y de una segura duración, y por lo mismo preferible, a otro cualquiera para transporte. Todo lo demás según reconocimiento del sargento y contramaestre destinados al intento podrá permanecer embarcado sin riesgo cuatro meses; pero el fabricado por Villa es aporte para diaria en el Puerto, sin embargo de que este ha firmado su duración con responsabilidad del costo por siete meses como anteriormente tengo representado a VS.”62

However, it takes more than flour to win a war. The king's weapons need vitamins and minerals for their operation. The same ones, coming from the wheat, are vital. With the husk of wheat they secured a source rich in phosphorus, zinc, iron and vitamins of the complex B. Bernardo de Alcalá, exerting like Minister of Real way, wrote 26 of February of 1777 to the same Carlos III, lines of his correspondence with Don Manuel de Pinazo, responsible for the collection of provisions. In them it reflected the following: “en ella [la correspondencia con Don Manuel de Pinazo] vera VS que desde el instante que se consideró oportuno el acopio de la nueva cosecha de trigo, no pensé en otra cosa que conseguir el número de fanegas que VS se sirvió señalar, y noticia positiva de su efecto para dar parte a VS pero sin embargo de este empeño, aun hoy estoy con el disgusto de no haberlo podido conseguir, bien que con el consuelo de no haber omitido diligencia para ello.”63

Food, specifically the energy source from wheat, is necessary. Without its circulation, the expedition and the king’s imperial power, is at grave risk. Then, he continues with the inventory of what has been collected up to that moment: “El trigo que he recibido asciende a 6500 fanegas de las cuales se muelen cada dia sesenta y dos fanegas, que componen sobre 90 quintales de harina cernida, y se va remitiendo en todas las lanchas a esa plaza en donde estarán en breve los 40 qqs que VS se sirvió prevenirme invirtiéndose aquí alguna corta porción en bizcocho, así por ser especial como porque me parece conveniente mantener los hornos en disposición de fabricar hasta 200 quintales diarios si fuese preciso.”64

The production of food must not only be constant but, moreover, the resources must be transported in a fast and efficient way. The economic sustainability gear is based on the maximum use of the merchandise that is available. The king's weapons have a cord of supplies that can reach 200 quintals, about 2,000 kilograms of food between wheat and biscuit. However, unlimited spending was not a premise of the royal authorities. The royal hacienda had orders from the crown that sought to maintain savings for cases of extreme necessity. Despite being able to raise production to about 100 bushels of wheat per day, milling would be maintained at 62 bushels a day, since, according to Alcalá: “por medir, recibir, y moler cada fanega de trigo, se necesita arina y trabajo de ensacarla con responsabilidad de su buena calidad (para lo que se marcan los sacos) no pago más que 6 reales a Sebastián Rodriguez, Juan Villa andrés Villercho, Juan de Sierra y José de Acosta, y 5½ reales a José del Solar.”65 The body of labor, production and storage depended entirely on the laborers and merchants of the city. The arrival of the troops increased the demand for products, energized the labor force and vitalized the storage capacity of Buenos Aires. The Royal Treasury could not give an unnecessary luxury of dispensing with this work force: “Si estas fanegas se hiciesen por la Real Hacienda era menester pagar almacenes, sujetos que recibiesen el trigo lo midiesen, pesasen para llevar a las zahorras reconociesen la calidad de las harinas y volviesen a pesarlas, las ensacasen, en todo lo que estarían empleados, además de los de cuenta y razón, un crecido numero de peones cuyos sueldos y jornales sin contar los extravíos a que está expuesto este género aumentarían el costo de cada quintal de arina cerrida más de un tercio al de 20 rreales que es el que hoy tiene por mi esmero.”66 As a result, we can evidence a part of reality. For 1775, in data of Martin Cuesta, the bush of wheat was to 10 reales, being the lowest price referenced throughout century XVIII. With the arrival of the expedition, it increased considerably to 50 reais per bushel, due to the growing demand for food.67 The royal forces were held through the merchants and sellers of the city. It was not an autochthonous military enterprise, but it worked hand in hand with the commercial dynamics of the River Plate port. And also, its surroundings.26−30

52AGN, IX, 1-1-3.

53Each bush is equivalent to 70 kilograms of wheat.

54AGN, IX, 1-1-3.

55Marchena Fernández (1983), 170. Cita carta de Gálvez. Aranjuez, 15 mayo 1779. Archivo General de Indias, Santa Fe, 557-A.

56AGN, IX, 1-1-2.

57As a measure of Spanish weight, it should be made clear that a yard is converted into 100 Castilian pounds. They equate to exactly 46.01 kilograms, or 4 arrobas. Moretti (1828), 137.

58Later, when analyzing the role of the Government through the Royal Treasury, these requirements will be analyzed.

59AGN, IX, 1-1-3.

60AGN, IX, 1-1-3.

61AGN, IX, 1-1-3.

62AGN, IX, 1-1-3.

63AGN, IX, 1-1-3.

64AGN, IX, 1-1-3.

65AGN, IX, 1-1-3.

66AGN, IX, 1-1-3.

67Cuesta (2007), 49.

Currently, a joint research project on the commercial circuit of the Río de la Plata is being developed, understood as a homogeneous economic space.68 For the research group, led by Fernando Jumar, the complex mercantile circuit was responsible for commercially connecting the port area of Buenos Aires and the region of Lima and Potosí, vital as a center for extracting metals, serving as "land ports" Santiago de Chile, Mendoza, Cordoba, Salta, Tucumán, among others. There are 371 leagues separating Buenos Aires from Santiago de Chile.69 The intermediate cities had a fundamental importance not only in the transport but also in the agricultural production of food, wine, vinegar, dried fruits and other products. Mendoza and Córdoba will then be characterized as the throat of commercial traffic, between the port of Buenos Aires and the economic space of the Kingdom of Chile. For the Cevallos expedition, this commercial apparatus became one of the most important supply chains in terms of production and security.

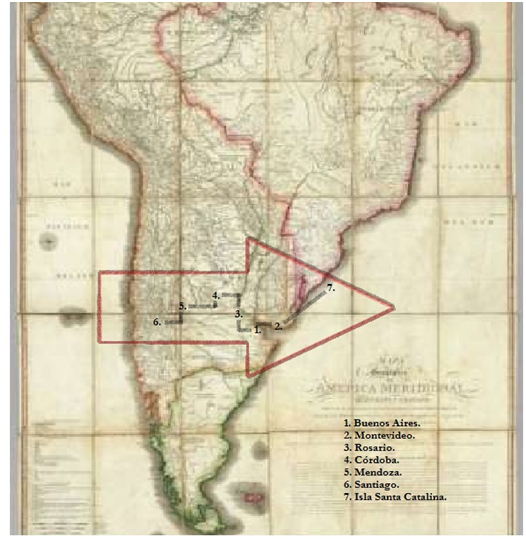

In a record of early 1777, Manuel de Pinazo receives the report of the expenses of production and transportation of wheat that is close to reaching Buenos Aires. A minimum of 62 imported daily bushels of wheat is needed. There is talk of a daily amount of 4,320 reais if all the wheat arrived from Chile. On average, monthly, only in the wheat trade, between production, transportation and the packaging process, the expedition was mobilizing around 100,000 real pesos monthly. This money, it should be noted, did not remain static in one of the actors of the commercial circuit. The importance of the expedition to the American economy lay in the constant exchange and continuous flow that produced the commercial dynamization. Now, it is evident that the commercialization and production caused by the arrival of the king's arms did not only have an economic impact on the city of Buenos Aires but was felt in most corners of the newly founded viceroyalty. The cities of Mendoza, Cordoba, Rosario, San Luis, San Juan, Santiago del Estero, among others, functioned as terrestrial ports. In these places, the population had to serve as a connection between the merchandise that came from the commercial route of Upper Peru and the Buenos Aires markets of the eastern plains. As a result, they had to expand their facilities to protect supplies while interconnecting transport. Merchandise that was not found on transport trolleys and was to be used in any way was marketed within the local markets of such land ports. This reality is worked in depth in the investigation of José Sovarzo and his analysis on the land port of Mendoza, one of the cities of the commercial circuit of the late eighteenth century.70 What I want to emphasize is that this trade feeds directly from the situation that is lived in Rio Grande. Cevallos needs these resources and its expedition becomes the main cause of trade boom during 1777. More than 130,000 kilograms of food are transported each month along these routes. Within a period of 5 months, trade was capable of transporting about 9,300 bushels of wheat, out of the 40,000 it requested from Alcalá for the maintenance of the whole expedition (Figure 2)71 (Table 1).

Figure 2 Map of South America, the commercial route moves from east to west, departing from Santiago to Montevideo, this last place of storage for the supplies with which the expedition counts.

Nombre de las embarcaciones del Rey |

Quintales de Bizcocho en limpio |

Quintales de Harina Cernida |

Quintales de Harina Salada |

Quintales de Tocino |

Quintales de Garbanzo |

Quintales de Arroz |

Navío San Agustín |

- |

434.39 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Idem Se|rie de transporte |

- |

601.11 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Fragata aurora n° 53 |

1621.72 |

- |

298.3 |

101.52 |

135.61 |

47.4 |

Fragata Nazareno n° 57 |

536.9 |

- |

145.73 |

- |

179.38 |

- |

Saeta los desamparados n° 20 |

824.1 |

- |

116.23 |

71.74 |

195.72 |

88.87 |

Saeta San quince y Santa Julieta n° 38 |

818.3 |

- |

156.51 |

29.93 |

236.5 |

- |

Saeta Misericordia n° 79 |

775.6 |

- |

152.65 |

- |

138.49 |

- |

Saeta la Merced n° 39 |

643.21 |

- |

85.3 |

69.24 |

163.39 |

- |

Saeta San Juan Bautista n°50 |

374.78 |

- |

115.85 |

- |

- |

- |

TOTAL |

5593.44 |

1035.5 |

1070.57 |

1048.64 |

1048.64 |

135.91 |

Nombre de las embarcaciones del Rey |

Quintales de lentejas |

Fanegas de Sal |

Sacos de cuero que llevaban bizcocho |

Sacos de cuero que se vaciaron |

Idem del envase de los garbanzos |

Idem del envase de arroz |

Navío San Agustín |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Idem Serie de transporte |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Fragata aurora n° 53 |

138.97 |

- |

723 |

70 |

70 |

24 |

Fragata Nazareno n° 57 |

102.39 |

- |

203 |

105 |

105 |

- |

Saeta los desamparados n° 20 |

71.4 |

4.11 |

392 |

110 |

110 |

43 |

Saeta San quince y Santa Julieta n° 38 |

- |

19.6 ½ |

358 |

130 |

130 |

- |

Saeta Misericordia n° 79 |

- |

- |

356 |

80 |

80 |

- |

Saeta la Merced n° 39 |

- |

11.7 |

267 |

100 |

100 |

- |

Saeta San Juan Bautista n°50 |

131.88 |

14.1 |

72 |

4 |

4 |

- |

Nombre de las embarcaciones del Rey |

Idem de las lentejas |

Idem del de la sal |

Sacos de lino que se vaciaron |

Guarnición con arcos de envase de carne |

Idem de tocino |

Tercera ración del de la carne |

Navío San Agustín |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Idem Serie de transporte |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Fragata aurora n° 53 |

56 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Fragata Nazareno n° 57 |

56 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Saeta los desamparados n° 20 |

40 |

10 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Saeta San quince y Santa Julieta n° 38 |

- |

12 |

- |

- |

6 |

4 |

Saeta Misericordia n° 79 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Saeta la Merced n° 39 |

- |

10 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Saeta San Juan Bautista n°50 |

53 |

10 |

45 |

6 |

- |

8 |

TOTAL |

205 |

42 |

45 |

6 |

6 |

12 |

Nombre de las embarcaciones del Rey |

Barriles de la tercera ración de la carne |

Barriles de la ración de tocino |

Sacos de cuero del envase de la harina |

Navío San Agustín |

- |

- |

102 |

Idem Serie de transporte |

- |

- |

165 |

Fragata aurora n° 53 |

170 |

59 |

- |

Fragata Nazareno n° 57 |

84 |

- |

- |

Saeta los desamparados n° 20 |

68 |

41 |

- |

Saeta San quince y Santa Julieta n° 38 |

86 |

- |

- |

Saeta Misericordia n° 79 |

90 |

- |

- |

Saeta la Merced n° 39 |

50 |

40 |

- |

Saeta San Juan Bautista n°50 |

38 |

- |

- |

TOTAL |

586 |

140 |

267 |

Fanegas de trigo |

Quintales de Harina |

Quintales de Bizcocho |

Quintales de minestra |

Quintales de Grasa |

Quintales de Sal |

Quintales de Carne salada |

||

Lo remitido por tierra |

- |

1953.79 |

1597.53 |

- |

- |

65.2 |

- |

|

Lo que queda existente en la ciudad |

1860 |

316 |

2821.65 |

1846 |

650 |

81.18 |

150 |

|

Quintales de Hierba |

Quintales de Tabaco |

Quintales de Ají |

Quintales de leña |

Sacos de cuero del envase - trigo |

Idem del Bizcocho |

|

Lo remitido por tierra |

149.48 |

51.7 |

29.65 |

- |

605 |

846 |

Lo que queda existente en la ciudad |

62.5 |

- |

40 |

16500 |

- |

- |

Sacos del envase-hierba |

Idem del tabaco |

Idem de la sal |

Idem del ají |

Carretas |

Carretillas |

|

Lo remitido por tierra |

82 |

23 |

48 |

15 |

127 |

42 |

Lo que queda existente en la ciudad |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Table 1 Wholesale state of the foodstuffs that have embarked in the convoy of the control of pedro de cevallos towards santa catalina

68This concept is extensively developed by Fernando and Biangardi (2014).

69Sovarzo (2014).

70Sovarzo (2014).

71Geographic Map of South America, Arranged and Recorded by D. Juan de la Cruz Cano and Olmedilla, Geogfo. Thought Of S.M. Individual of the Royal Academy of San Fernando, and gives the Basque Society of the Friends of the Country; Bearing in mind several maps and original news according to Astronomical Observations, Year 1775. London, published by William Faden, Geographer of the King, and Prince of Wales, January 1, 1799. "On this occasion, the commercial route moves from east to west, departing from Santiago to Montevideo, this last place of storage for the supplies with which the expedition counts.

Within the organization of the Royal Treasury, factors of unification and control were becoming increasingly important. Towards 1750 the system reached its maturity.72 This fiscal control body played a fundamental role in the collection, administration and shipment of food that would feed the Cevallos expedition in the first half of the year 1777. The figure of 14,916 pesos real silver is what the Real Estate injected of direct form to the guild of sifted flour merchants and sponge cake manufacturers of the city.73 6,182 pesos destined the Real Hacienda to the commercialization of 1,608 bushels of wheat, paying salaried workers for cleaning, grinding, sifting and storing. According to the report of Sgt. Antonio Carrera, presented to the Royal Treasury, the transportation of said merchandise to Rio Grande, for the supply of the expedition, had a cost of 1,580 pesos.74 This sum is divided into the contracting of 87 carts, the payment to the day laborers who carried them and unloaded the merchandise from the vessels and all the material for the packaging and storage process, from its departure in Buenos Aires until the arrival at the Santa Catalina Island.75 The fiscal-military state is not only implemented in the collection of taxes, which is the first thing to be seen, but in the management and distribution of the money in the royal coffers. Taxation includes the management of the treasury and its subsequent distribution to the needs of the empire.31−39

To see a specific case, Don Mateo Petizco, Treasurer of the Navy of Buenos Aires, in charge of collecting the money destined to the payment of the production, storage and transport of the provisions that fed the expedition, would receive, by March of the year 1777, the sum Of 30,000 real pesos coming from the coffers of the Real Estate.76 This amount of money would go to food assisstors charged with "satisfying some of the many creditors, who have so far supplied various quantities of supplies”.77 These figures were also fed by the incoming resources of the royal cajas de Lima that found in Buenos Aires a market to provide. Real money reactivated trade, trade stimulated by militarization. Trade impacted on all components of society. From the governor, in charge of the logistics and maintenance of the same, to the humble manufacturers, just as important in the commercial gear that activated the arrival of the expeditionary force, all perceived the commercial dynamization. Don Juan Villa, maker of biscuit, worker by commercial contract, presented the order to the Royal Treasury on the existence of one thousand six hundred quintals of bread, “el cual lo sacaré y marcaré con una V a fuego, y remitiré en las lanchas que se me destinaron para llevar a Montevideo en donde debe ponerse separado, y para verificación de su buena calidad, y subsistencia lo aseguro por siete meses contados desde la fecha, y siempre que en el referido tiempo se perdiere por falta de su fabrica quedo responsable con mi personaly vienes a reponer dicha cantidad de bizcocho.”78 Quantity and quality, the two characteristics were forced to meet each trader. This document was signed under oath with two witnesses in Buenos Aires on January 7, 1777, proof that even before the arrival of the expedition the governorate in Buenos Aires was preparing the food collection. Subsequently, 18 days later, the report that guaranteed a government order from Vértiz, where the urgent preparation of food was requested, arrived in the office of the Royal Treasury. It has been arranged "to embark for that port 27 barrels of salted meat and contracted for all the immediate February up to 1000 qqs of equal spice with precision that I have to deliver 100 barrels in 15 of the month.”79 The flow should not only be timely but constant. Each month a minimum of food for the expedition must be met. The Royal Treasury guaranteed in this process an adequate production of the food that Cevallos would request three months later. In addition, storage was of vital importance, as was production and transportation. De Alcalá would write to Vértiz on January 29 a report about the stores available for the real service. Once the large storage spaces have been completed, "it is considered as advisable that the remittances of this square to be used for all the sponge cake, guns, butter, salted meats, bacon and fat which is available to prove its embarkation”.80 The Real Estate, permeated by the Bourbon reforms, had to handle accurate information month after month. Production in Buenos Aires, merchandise from the commercial circuit of Chile, transport by the Rio de la Plata, storage in Montevideo, was always found under the organizational eye of Her Majesty's offices.

72Idea worked in Ruiz (1994), 77.

73AGN, IX, 4-3-7.

74As the captain wrote to Governor Joseph Vértiz, the boats used to transport food through the Rio de la Plata had the capacity to carry on average 138 sacks of sponge cake, 60 sacks of flour, 68 barrels of meat and 8 balls of grease. Melchor González, freight forwarder and transporter, would receive 70 pesos real for the payment of the transport of the provisions. AGN, IX, 1-1-3.

75AGN, IX, 4-3-7.

76AGN, IX, 1-1-3.

77AGN, IX, 1-1-3.

78AGN, IX, 1-1-3.

79AGN, IX, 1-1-3.

80AGN, IX, 1-1-3.

From the desk of Joseph de Galvez, visitor and reformer of the Spanish empire, secretary of the Indies from 1776,81 an order would be signed in the name of the King addressed to the governor Vértiz, dated June 1777. In said writing, it was affirmed that, under the knowledge of His Majesty, the royal coffers of Buenos Aires have received the sum of 740,637 pesos. This amount should have been used only "in the monthly payments that are made to the troop, the collection of food for the expedition and other indispensable important objects of Royal Service.”82 From this we can conclude several things. As more relevant, one of the principles of the fiscal-military state becomes evident. The resources of the State, for the most part, had to be destined to the maintenance of the military apparatus. Such superiority allowed for an increase in the royal treasury, guaranteeing control of production, commercial flow and imperial mercantilism (allowing a subsequent investment in education, health, among others). We have seen throughout this little journey through the years that the war against the Portuguese invasion brought a military and economic stability to the newly founded Viceroyalty of La Plata. The production of resources and provisions to supply the king's weapons was constant. To acquire these resources, royal coffers and money from the same peninsula were used, which would go against the old colonial logics. In my view, having already drawn attention to the conceptual problem about "the colony", a more correct option is to study these types of societies as Hispano-American proper to the Old Regime. It is a complex polycentric system, often with juxtaposed powers, articulated in terms of pursuing and achieving certain imperial and regional objectives. That said, the conception of fiscal-military status, as was explained in the brief historiographic balance at the beginning of this paper, is a better characterized concept to refer to the logic of the Spanish state and its units, peninsular and American. The continuous growth of the markets and the dynamization of the local commerce and the commercial routes with other latitudes became evident, articulating around imperial objectives (the military defense of the Empire) and local (the sale of American merchandise paid with Spanish money).

For the Spanish empire of King Charles III, the mobilization of economic resources obeyed a political order. The desire to maintain the dominion of its territories and to organize it in a more pragmatic way, with the foundation of the Viceroyalty of the Rio de la Plata, was the one that mobilized both the money coming from its own royal coffers in the peninsula and the resources found in the American continent. These resources were the ones that fueled the war against the Portuguese in the eastern band, echoing a political guideline. In addition, as a fiscal-military state, it was sought to maintain a powerful armed force that not only secured the king's domains but also was able to manage the production and collection of resources. We were able to demonstrate through the sources that it was mainly the militia and the spanish generals who were in charge of transporting, storing and distributing the provisions and money, supported by the officials of the Real Estate. This first objective, fundamental within the fiscal-military state, opens the way to the fulfillment of the second, since it guaranteed maneuverability within a confrontation between empires, being able to act defensive and offensively, as exemplified in the assault on Island Santa Catalina (Table 2).

Chile |

Reales de plata |

La fanega de trigo compone 3½ quintillas escasas de la de esta ciudad de Buenos Aires, se conceptua que sea su valor |

16 |

Su flete desde Chile a Mendoza |

16 |

Desde mendoza a esta ciudad |

32 |

El saco |

6 |

Total |

70 |

Mendoza |

Reales de Plata |

La fanega de trigo compone 3½ quartillas cargas de las de esta, se considera su valor |

16 |

El flete desde Mendoza aquí |

32 |

El saco |

3 |

Total |

51 |

Córdoba |

Reales de Plata |

La fanega de trigo corresponde lo mismo que la de Buenos Aires, se conceptúa su valor |

16 |

El flete desde Córdoba aquí |

16 |

El saco |

2 |

Total |

34 |

Santiago Estero |

|

Poco más o menos lo mismo que Córdoba |

Table 2 News of the price and cost of transport of wheat of the places that will be expressed

In order to address the third objective of the fiscal-military state, which I believe to be true, we must investigate what happened after the invasion and confrontation with the Portuguese. On June 11, 1777, the royal order would arrive, marking the end of hostilities. In the words of Charles III himself: “luego que recibía esta mi real cédula se acaben absolutamente de presente y futuro las hostilidades y toda efusión de sangre, a cuyo fin os mando que sin pérdida de tiempo deis las más eficaces y positivas órdenes a todos los generales. Gobernadores, comandantes y demás de mar y tierra, de esos mis dominios que se abstengan de cometer acto alguno de hostilidad contra los vasallos, y territorios de la Reyna fidelsisima, así por mar como por tierra, previniéndoles igualmente que eviten con el mayor cuidado y vigilancia cualquiera disturbios, o perturbación entre los súbditos de las dos coronas.”83 According to Juan Carlos Luzuriaga, it would be until October 1 that Spaniards and Portuguese would sign the Treaty of San Ildefonso. This document "granted Spain the Colonia del Sacramento and the Eastern Jesuit Missions of Paraguay. Portugal, moreover, promised to give up its aspirations on the Philippines and the Marianas and to give Spain to the islands of Fernando Poo and Annobón. In exchange, Portugal would keep Rio Grande de San Pedro and recover the island of Santa Catalina.”84 When peace arrived, commerce and the market would feed on what the war left behind. On September 23, it would be Galvez who would give the good news, that it would not be surprising if they were already known on American soil. The secretary of the Indies would affirm that "for any movement that might be offered there, I warn you that the surplus of the expedition is left with all that you do to the case for the purposes you wish and that in the Not having to fill a line, advise anyone to arrange their shipment.”85 As a fulfillment of the third fundamental objective of the Spanish fiscal-military state of Carlos III, the continuous flow of resources continues. The money brought by the expedition, which, as we have seen, reached a figure close to 800,000 pesos of 8 reales and the profits produced for the market by the sale of food directly fed the local economy, stimulating trade, The interconnection of cities and the transit of trade routes. The reader will ask for some previous data with which a comparison can be seen in relation to this amount of money with which he used to circulate by the viceroyalty in previous years. In the article written by Fernando Jumar and Maria Emilia Sandrín the public expenditure managed through the Real Estate is analyzed like dynamizer of the local economy, in the years of 1734 to 1742. According to the account letters of the Caja de Buenos Aires, for this period, in the 8 years that elapse, the branches of real estate, deposits, half anatas and camera penalties amount to a total of 652,740 pesos to 8 reales. A little more than 30 years later one can understand the extent of the impact of the second expedition of Pedro de Cevallos on the local economy. Even this same investigation serves us to present a second case about a previous military expedition. The site to Colonia de Sacramento by the armed forces of the Spanish crown that took place in 1735 and extended until 1737 left the following statistical data: in total, between expenses of feeding, salary and management expenses and camping expenses are Allocated 226,619 pesos to 8 reales. Money that, according to Sandrín and Jumar, directly stimulated the local commerce since more than 60% of the resources were bought in the local markets.86 The growth for 1777 is evident.

I do not want to propose, as might have been perceived in the text, that the fiscal-military state is an explanation for the conceptual problem that the term "colony" implies. There are better proposals that fully explain the whole and not just one of its parts. The concept of "polycentric monarchy", which emphasizes a socioeconomic order based on multiple centers of power, is one of them. In truth, there was not a single political or economic authority that directed at its whim the fate of American and peninsular lands. Instead, from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century a network of local and imperial powers was built, operating under the terms of constant negotiation, where it is often the American actor, not the peninsular, who has the last word.87 If the polycentric monarchy explains the operation of the whole, it is the fiscal-military state that envisions one of its most important dimensions: the means that the crown sets in motion to take an active part in the negotiation process.

81Marchena Fernández (1983).

82AGN, IX, 4-5-1.

83AGN, IX, 4-3-8.

84Luzuriaga (2008).

85AGN, IX, 4-5-1.

86Jumar y Sandrín (2015), 242.

87There are to date several historiographical examples that raise the question of the polycentric monarchy. In my opinion, one of the most complete is the compilation made in 2014 with the support of the Seneca Foundation, the Study Center of German and Red Culuminaria. V. Cardim, Herzog y Ruiz Ibáñez (2012).

None.

Author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

©2018 Serrato. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.