Journal of

eISSN: 2573-2897

Mini Review Volume 2 Issue 1

Perm Federal Research Center, Russian Academy of Sciences, Russia

Correspondence: Krylasova NB, Perm Federal Research Center, Russian Academy of Sciences, Russia

Received: November 02, 2017 | Published: November 6, 2017

Citation: Krylasova NB. Origin of knitting in Eastern Europe (On the first finding of a fragment of a knitted product in the Urals). J His Arch & Anthropol Sci. 2017;2(1):15-17. DOI: 10.15406/jhaas.2017.02.00043

The issue of the origin and distribution of knitting on knitting needles in the territory of Eastern Europe is still poorly studied; no special studies on this topic have been conducted. At the same time, in the process of archaeological research a source base is gradually being formed, which makes it possible to answer the question of the time of penetration of knitting into the culture of the medieval population. Honestly, in the Urals one of the burials of the X century, a small piece of a sock or stocking is found, which indicates the early spread of knitting among the indigenous Finno-Ugric population.

Keywords: Russia, urals, archeology, middle ages, knitting

Knitting is the process of making products from continuous yarns. It is believed that at first knit simply on the fingers and later invented knitting needles and a hook. An elementary unit of a knitted product is a loop formed from a thread by means of spokes or a hook. In ancient times, most often knitting needles used are bone, wooden, metal. Knitting with knitting needles is a process of converting a continuous thread into loops which joins together horizontally and vertically, form a continuous web. The origin of knitting in Eastern Europe has been little studied due to the lack of a source base.

In historical essays accompanying handicraft allowances, it is asserted that the homeland of knitting is the Middle East. The oldest knit article is a child's sock from the Egyptian tomb, which is more than IV thousand years old. Knitted socks found in Coptic burial of the 5th century. It is believed that knitting penetrated into Europe through the Copts or was borrowed during the Crusades from the Arabs, who were considered the most skillful knitters in the middle Ages. For example, fragments of the original Arabic knitting (about the 7th-9th centuries AD) with complex multicolored geometric patterns and a small part of the scarf with a similar ornament of about the 12th century are known. AD In the opinion of some authors, the penetration of knitting on needles into Europe occurred in the 9th century, according to others not earlier than the 12th-13th centuries. Knitting has spread in Spain, Italy, France, England, Scotland, Germany, in the Baltic countries. Most often knitted mittens knitted needles, socks and stockings. In France in 1206 the first book on Etienne Pualo's needlework was published, in which it was also spoken about knitting hats. At the end of the XV-XVI century, knitting became especially popular in Europe, which was due to the widespread knitted stockings that were very expensive and were considered an exquisite gift.

On the territory of Russia, according to art historians and ethnographers, knitting on knitting needles appeared late, from Western Europe and the Finno-Ugric culture penetrated from the Russians even later. So, according to SV Ivanov and GN Klimova, knitting on knitting needles drooped from the West first to Permian Finns who lived in the western foothills of the Urals and from them to the peoples of Western Siberia not earlier than the 17th-18th centuries.1,2 At the same time, archaeological data remain unheeded, while on the territory of Russia are known finds of knitted products, which date from an earlier time.

The earliest is the fragment of a knitted woolen product from the female burial No. 1 of the Chelmuzhi-2 mound in Prionezhye. In the rich inventory of this burial there were seven coins, the latest date of which was 988/989. Thus, the burial refers to the boundary of the 10th-11th centuries.3 As OI David,4 for a small piece of knitted product is difficult to determine its functional purpose, but the very fact of the find is very interesting, since knitted products are rare finds.4 To a somewhat later time are findings of knitted goods from the cities of North-Western Russia, where woolen socks, stockings, shoes, knitted mittens are found.5−8 For example, found in the late 12th century layer. In Beloozero, knitted woolen products (a slipper-slipper, a children's slipper and sock fragments, according to the description of LA Golubeva, are distinguished by even and beautiful knitting.) By the way of knitting, the products are reminiscent of old Russian stockings without heels, which in the middle of the 19th century were knit rounded with a single (often bone) knitting needle.5

In the Urals, many samples of textiles are known in medieval materials: fragments of canvas and woolen fabrics of plain linen and twill weave imported silk taffeta, woven and woven belts. There were also speculations about the existence of knitting in this territory. For example, RD Goldina9 came to this conclusion on the basis of finds of long bone needles, which could serve as knitting needles. In her opinion knitted stockings and mittens.9

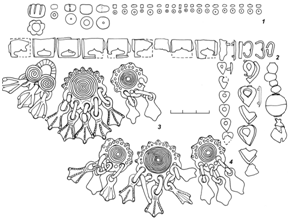

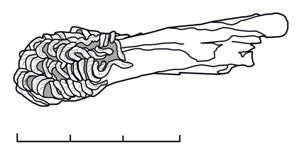

In 2009, a fragment of a knitted product was discovered for the first time on the territory of Permsky Krai. This, perhaps, is the most eastern of known to date such finds. This fragment was found in the burial No. 166 of the Christmas burial ground in the Perm region. In the funeral inventory there were fragments of a ceramic vessel, glass beads and beads (Figure 1(1)), lining sets, bronze beads and a bells (Figure 1(2)), as well as 6 bronze noisy pendants with a base in the form of an umbon and pendants in the form of duck legs (Figure 1(3-4)). Similar pendants were used to decorate the shoes of the Volga Finns. At the Christmas burial ground they usually served to decorate women's waist bags, but in burial No. 166 they, certainly, served as an ornament of footwear. The small depth of the graves and the features of the funeral rite do not contribute to the good preservation of the skeletons. But in this case, thanks to the preserving properties of copper oxides, the bones of the metatarsal were preserved under the suspensions, which, judging from the conclusion of the anthropologist, lay in anatomical order and were closed, which indicates that the deceased was shod in dense shoes. On one of the bones a small fragment of the sock, connected by simple stocking is preserved (Figure 2).

According to the composition of the funeral inventory, the burial date back to the end of the tenth century. In the very burial of narrowly dated things have not been met, but in the neighboring burials 7 coins are collected, the chronological range of which is from 929/930 to 980/981. Thus, the burial No. 166 of the Christmas burial ground is chronologically close to the burial from the Chelmuzhi-2 mound. Which of the bone spokes, in many presented in medieval materials of the Perm region, could be used for knitting, is not reliably established. Most of the needles, made mainly from the bones of large sturgeons (Figure 3), are thick enough and not suitable for sewing - they could not pierce the dense tissue that was widespread at that time and even more so the skin. On fragments of products with preserved seams, it can be judged that they sewed with thin steel needles similar to modern ones which are known from the materials of the excavation of settlements. But most of the known bone needles are too short to serve as knitting needles. Perhaps they were the tips of a flexible spoke. Such a spoke, which is still used today, consists of two tips connected by a flexible cord to which the loops are dropped. Many of the known bone needles can be referred to the tips of such a knitting needle. Less common are relatively long needles that could be used for knitting around five spokes. At the site of the Kupros ancient settlement in the Perm region, 5 bone spokes were found in one place (Figure 4) just the necessary kit for knitting around. In the course of the experiment it was found that these spokes are very convenient for knitting around small products (for example, socks and mittens).

The earliest European patterns of knitting come from the Finno-Ugric burials. Finno-Ugrians, in particular, who inhabited the territory of the Perm region, could easily borrow the knitting skill from the Arabs, with whom they had strong economic ties. And most likely it was the Finno-Ugrians and not Western Europe that Russian skill adopted.

None.

Authors declare there is no conflict of interest.

©2017 Krylasova. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.