Journal of

eISSN: 2573-2897

Review Article Volume 3 Issue 3

Leader researcher, Department of Archaeology, Institute of Latvian history, Latvia

Correspondence: Roberts Spirģis, Leader researcher, Department of Archaeology, Institute of Latvian history, Latvia

Received: February 15, 2018 | Published: June 14, 2018

Citation: Spirgis R. Finds in Latvia of 13th-century pilgrims’ crosses from the Holy Land. J His Arch & Anthropol Sci. 2018;3(3):494-499. DOI: 10.15406/jhaas.2018.03.00123

The paper is devoted to three finds of mother-of-pearl crosses from Latvia, representing two different types of such artifacts. The earliest crosses, in the form of the Kouvouklionof the Tomb of Christ, from Riga and Turaida, are pilgrims’ souvenirs from Latin kingdoms in Palestine. Two asphalt crosses found in Riga are possibly also connected with pilgrimages to the Holy Land.1 At that time the inhabitants of Livonia could reach the Levant either by a western or an eastern route. The cross from Cēsis takes us back to the events of the Livonian War in 1577. This find points out to the considerable role of items of personal piety among the Russian soldiers. The cross could have been made at Athos or in Russia itself using imported raw material. In medieval Livonia, naturally available materials, such as wood, clay, iron, wool, bone, limestone, leather, etc., were used in crafts, along with imported precious and non-ferrous metals: silver, copper, tin and lead. Objects made of these materials are widely represented among archaeological finds. On the other hand, items fashioned from non-traditional materials merit particular attention for the information they can provide concerning links with distant lands.

Keywords: mother-of-pearl, museum, Latvian history, pilgrims

1The preparation of this article has been supported from the science base funding of the Institute of Latvian History (Project: The territory of Latvia as a zone of contact between different cultural spaces, religions, and political, social and economic interests from prehistory up to the present day, No. D2015/AZ85).

Finds of mother-of-pearl crosses

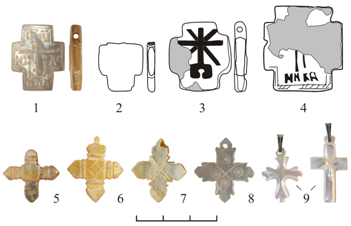

Important in this context are finds of crosses made of mother-of-pearl, or aragonite. The archaeological material from Latvia is rich in objects of personal piety. Thus, an article published by Ēvalds Mugurēvičs in 1974 covers some 500 crosses spanning the period from the 11th to the 15th century.1 However, only three examples made from mother-of-pearl are known.1 One of these was found at the Alberta laukums site in Riga (excavation in 1960 by the Museum of the History of Riga, under the direction of Melita Vilsone). It is in the form of a Greek cross, measuring 19×20 mm (Figure 11). The aragonite plaque is almost 4 mm thick. The cross has a square at the centre, while the arms are triangular, with a projecting band at the base. The upper arm had a hole drilled from the side, at which point it has broken. The front of the cross is yellowish and polished smooth, while the back is brownish and rough. Unfortunately, because the context record is inadequate, the object must be treated as equivalent to a stray find. There is a similar mother-of-pearl cross (Figure 1(2)) from Turaida Castle (excavation by the Institute of Latvian History in 1981, directed by Jānis Graudonis). This piece is only a few millimetres larger than the Riga find, but is flat rather than three-dimensional, having been cut from mother-of-pearl only 2.7 mm thick. There are circle-and-dot designs on both faces and a slanting cross carved in the centre. The object was found at the edge of the slope outside the castle.

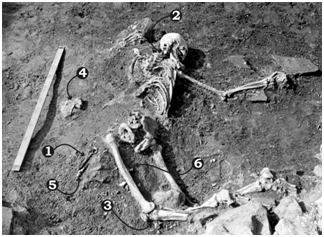

A third cross has been found on the slope outside Cēsis Castle (Figure 1(3)), at the neck of a fallen Russian solder (excavation by the Institute of Latvian History in 1985, directed by Zigrīda Apala). Because of the curvature of the shell, the front of the cross is somewhat convex, its thickness decreasing from 4.2 to 3 mm. The object is 23.3 mm long and only 18.7 mm wide, the lateral arms being almost half the length of the vertical ones. At the top is a drilled perforation for suspension, 2.3 mm in diameter. The front of the cross is light coloured, with a pearly lustre. At centre is the so-called Golgotha Cross–the hill of Golgotha is represented by a step at the foot of the cross. Depicted at the side is a spear with its shaft, having a round sponge at the end, along with the Cyrillic monogram IC XP commonly found on Orthodox crosses. At the top there are ligatures ЦР and СЛ and below the word НИКА (“Jesus Christ, King of Glory, Victory”). The images are placed within a frame. The back is smooth and yellowish. The depiction is thought to have been etched into the mother-of-pearl. The body of the fallen man was covered by rubble and lay in an unnatural prone position Figure 2. The bones of the skeleton had been shattered. An axe was also found with the deceased and by the left side of the pelvis was a pair of scissors, along with the iron tip of a knife sheath and the remains of a purse with 16th-century Russian coins. A crossbow bolt recovered near the left knee may indicate a wound to the leg. When the bones were removed, an impression from decoration on a kaftan was seen in the cultural layer.

Figure 1 Mother-of-pearl crosses found in Latvia: (1) Cross from Alberta laukums. (2) Cross from Turaida Castle ruins. (3) Cross from Cēsis Castle ruins.

Figure 2 Skeletal remains of a Russian soldier discovered on the west slope of Cēsis Castle (skeleton no. 7). (1) Iron scissors. (2) Mother-of-pearl cross. (3) Iron crossbow bolt. (4) Iron axe. (5) Fragment of iron knife blade. (6) Remains of a purse with silver coins.

Mother-of-pearl crosses as pilgrims’ souvenirs

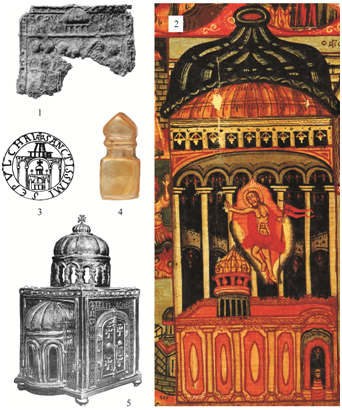

Pieces analogous to the crosses from Riga and Turaida have been found in fairly large numbers in Eastern Europe, as well as in Turkey, Syria and Palestine Figure 3. The time of production corresponds to the period of the Crusades: from the 12th up to the end of the 13th century. In the middle Ages the cross had a particular semantic significance in religion as an item of personal piety. In this particular case the choice of material is in itself significant. Semantically, the shell relates to the symbolism of the Mother of God and Jesus Christ, the Son of God being compared to a precious pearl in the womb of the Virgin Mary. The shell was also a symbol of the Tomb of Jesus (Figure 4) and the Resurrection.2 Even nowadays, mother-of-pearl is a traditional material for making pilgrims’ souvenirs in the Holy Land (Figure 5(10)). It is possible that the rounded form of the projections, with a raised band at the base, seen at the ends of the arms of the mother-of-pearl cross from Riga, was inspired by church domes. It may be added that the small chapel, known as the Kouvouklion (Aedicula), located above the Tomb of Jesus in the Church of the Resurrection in Jerusalem, also has a small domed tower. In this ensemble Figure 4, the dome symbolises the Resurrection and the triumph of Jesus Christ over death.3 The Turaida cross represents the same form. Even though the composition is simpler, the triangular projections at the ends of the flat arms of the cross schematically represent a dome. This is seen from a comparison between the crosses from Latvia and religious symbols found in Palestine, forming a unified typological series (Figure 5(6─9)).

Figure 3 Distribution of mother-of-pearl crosses. (1) Major towns, settlements and fortifications. (2) Find-spots of mother-of-pearl crosses. (3) Finds of uncertain or imprecisely known provenience in Syria and Asia Minor.

Figure 4 Pictures of the Kouvouklion of God’s tomb. (1) lead-tin alloy pilgrim token from hillfort Gorodishsche near village Shepetovka in Ukraine, 12th–13th centuries. (2) Passage of the icon “Palestinian topography”, Jerusalem, 1876. (3) Stamp of canon of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre on the 1175 document. (4) A part of the Mother-of-pearl cross from Alberta laukums, Riga. (5) reliquiarium of Aahen, Antioch, end of the 10th–11th centuries.

Figure 5 Mother-of-pearl crosses. (1) Cross from Cēsis Castle ruins (Latvia). (2) Cross from Pskov (Russia). (3) Cross from Avtunichi settlement (Ukraine). (4) Cross from Pskov. (5) Cross from Riga (Latvia). (6-7) crosses from Atlit Castle ruins (Izrael)

It may be noted that archaeological mother-of-pearl crosses were first identified as pilgrims’ souvenirs in the works by Russian researcher Aleksandr Musin.2 Finds of a whole series of such crosses (Figure 5(7,8)) in the 13th-century layer of Atlit Castle provide a clear indication that such crosses were also made in Palestine for pilgrims in the time of the Crusades.4 This so-called “Pilgrims’ Castle”–Château Pèlerin–was a major port receiving pilgrims travelling from Europe to the Holy Land. The find from Cēsis relates to the events of the Livonian War: in September 1577, besieged by the forces of Russian Tsar Ivan the Harsh and facing inevitable capture by the Russians, the noble residents of the castle preferred suicide and blew themselves up.5 As a result, a soldier of the attacking forces also remained buried under the ruins of the west block of the castle right up to the time of the excavation. In contrast to the crosses showing the form of a Kouvouklion, rectilinear pieces resembling the find from Cēsis are much less common. The author is aware of two crosses from Pskov, one of which has no inscription (Figure 5(3)), while the other, found in a burial in the churchyard of the Church of St John the Merciful (Иоанна Милостивого), albeit very poorly preserved (Figure 5(5)), has remains of a similar depiction of the Golgotha Cross and inscriptions. One more cross of a similar form (Figure 5(4)) has been recovered at the site of Avtunichi, Chernihiv Region, which, starting from the second half of the 14th century belonged to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

The cross from Cēsis does not have such an unambiguous connection with pilgrim culture as the crosses in the shape of the Kouvouklion from Riga and Turaida. The find context and the parallels with the find from Pskov illustrate the fact that this town served as the base for the Russian attack on Livonia,6 where forces from all regions of Russia assembled. The Cyrillic inscription on the cross raises certain questions. There was a boom in distant pilgrimages to the Holy Land during the age of the Crusades, when the Latin States were established in Palestine. Because of the expulsion of the Christians from the Holy Land and the Mongol invasion in the 13th century, pilgrimages from Old Russia were very difficult to make in the next centuries. Likewise, in the time of the Ottoman Empire, Christians from Europe did not have free access to the holy sites of Palestine. 16th-century written sources mention individual trips by Russian envoys, the travellers being protected by letters of safe conduct.7

In the Late Middle Ages, the working of mother-of-pearl encompassed a wider area. There is evidence that, starting from the mid 14th century, ritual objects of this material began to be made, primarily for pilgrims, in Veliko Tarnovo (Велико Търново), the capital of what is known as the Second Bulgarian Empire. Moreover, in cases where access to marine raw material was problematic, aragonite from freshwater mussels was used.8 Organised shell-working in Veliko Tarnovo is thought to have been connected with the spread of the teachings of the hermitic Hesychasts from Athos. The theme of the Transfiguration of Christ had an important place in the hermitic teachings. And because of its capacity for splitting light rays into the colours of the spectrum, mother-of-pearl obtained the significance of a symbol of the divine Light of Tabor.9 The blossoming of spiritual life and Christian ritual crafts at Veliko Tarnovo was connected with the attempt to create a new global centre of Orthodoxy in Bulgaria, but this was doomed to failure. In the late 14th century, through the activity of Cyprian from Tarnovo, who became the Metropolitan of Kiev, Lithuania and all Rus, similar ideas and the Hesychast movement itself spread further northwards.10

Judging from an inventory, craft activity was well developed at the Old Russian monastery at Athos already in the 12th century: there was a scriptorium, an icon workshop and a smithy.11 After a long interruption, regular contacts between Athos and Russia began to be re-established, particularly in the 16th century, as indicated not only by the frequent embassies of the monks in Moscow,12 but also by the development of the Monastery of Athos into an unusual kind of Greek language learning centre for Muscovy’s foreign affairs department.13 Thus, it is not impossible that the Cēsis cross was made in Athos or Bulgaria. It is also possible that the Cēsis cross was made from a shell found on the shore of the Aegean or Mediterranean coast by a Russian craftsman inspired by a pilgrimage. Thus, written sources preserve a report about a visit by the Muscovite Fyodor to Constantinople and Athos in 1582. It seems that Fyodor was professionally specialised in the manufacture of crosses.14 The deep relief and quality of the image on the Cēsis cross also corresponds to the stylistic characteristics of Moscow art of that time.15

Determination of the mother-of-pearl

Since culture-historical analysis in archaeology always benefits from validation with the help of the exact sciences, in the course of working with mother-of-pearl crosses, I turned to specialists in these fields. Questions arise because molluscs whose shells could be used to obtain a sufficient amount of aragonite to make such crosses do not inhabit the Baltic Sea. On the other hand, there are various mussels of the genera Unio and Margaritifera inhabiting rivers (Margaritifera margaritifera, Unio crassus, Unio tumidus) whose shells could have served as material for making small artefacts. Judging from the colour of the mother-of-pearl used for the Riga cross and the thickness of the growth layers, it comes from a shell of a mollusc from the genus Ostrea (visual examination does not permit determination to species), distributed in the Black Sea and Mediterranean. The same may be said of the Cēsis cross, which is likewise so thick that it could not have been made from aragonite of a freshwater mussel. On the other hand, the Turaida find is bluish in colour and thinner, which means that it might have been made from local material. However, the x-ray fluorescence analysis of all three crosses from present-day Latvia, conducted at the Assay Office of Latvia, indicates that the aragonite is of marine origin. Thus, manganese (Mn) is a component of pearls and mother-of-pearl from freshwater mussels, but this element is absent from the spectra. (The author is most grateful to Edgars Dreijers, senior zoologist and malacologist of the Latvian Museum of Natural History and Pēteris Brangulis of the Assay Office of Latvia, for analysis and consultation.)

Bitumen crosses

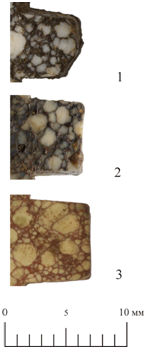

When the mother-of-pearl crosses were being investigated, two stone crosses, likewise found at the Alberta laukums site in Riga, also attracted attention. These crosses, about 20 mm long and 13.5–15.5 mm wide, are 6–7 mm thick, made of a grey material with light-coloured, rounded inclusions (Figure 6). There are similar crosses in Ancient Russian material, regarded as being made from Ovruch pyrophyllite slate. Indeed, production sites have been archaeologically excavated in north-western Ukraine that specialised in the extraction and processing of this rock. In the course of excavation, proof of the production of pyrophyllite crosses has been obtained, in the form of hundreds of rejected, broken and unfinished crosses.3

However, already twenty years ago specialists of the Faculty of Geography and Earth Sciences of the University of Latvia (A.Sabiele, G.Stinkulis) identified the material used to make the Riga crosses as bitumen with incorporated quartz grains.16 In the course of preparation of this article, the Assay Office of Latvia performed Raman spectroscopy on the crosses, identifying aluminium and silica oxides in the granular inclusions of the crosses. The dark matrix was found to have a high content of carbon, indicating its organic character, which excludes the possibility that the crosses consist of a monolithic rock such as pyrophyllite. Thus, the analysis confirmed the conclusion that the crosses were made of bitumen.

Indeed, an enlarged photograph of the crosses is sufficient to show that the grey matrix has exuded, forming small bulges projecting beyond the faces of the two Riga crosses (Figure 7(1,2)). By contrast, the items from Ovruch have smooth surfaces and feel greasy to the touch (Figure 7(3)). The entire surface is uniformly shiny and polished, with red veins. In terms of composition, pyrophyllite consists of aluminium silicate hydroxide and there should be no exudation from the layers. Indeed it is a refractory material, with a melting point of 1540º–1630º17 and could be used to make casting moulds. The manufacture of spindle whorls, quernstones and other rotary elements from this material demonstrates its resistance to mechanical abrasion and centrifugal force.18 Bitumen is an altogether different kind of material: a form of petroleum, with hard mineral materials, gravel or sand, embedded in the matrix. Bitumen melts at a temperature as low as 100º and clearly displays a degree of viscosity. Accordingly, it is concluded that the medieval stone crosses with rounded inclusions do not all have the same composition and origin and the examples from Riga have no connection with the pyrophyllite industry of the hills at Ovruch.

Figure 7 Erlargement of bitumen and pyrophyllite crosses. (1-2) Bitumen crosses from Riga. (3) Pyrophyllite cross from Zemgale.

Of course, hydrocarbons were not nearly as important as they are at the present day. Nevertheless, they did have their uses in those days as well. In the middle Ages all the known oil sources around the Mediterranean were strictly supervised by the Byzantines, because oil was the raw material for “Greek fire”. Bitumen is also known to have been the incendiary material used in nozzles used to squirt “Greek fire”. The best-known source of bitumen was the Dead Sea, which was accordingly known as the “Asphalt Sea”.19 Diodorus of Sicily, Flavius Josephus and Vitruvius all record that the residents of the coast of the Asphalt Sea collected the substance, known as Jewish bitumen and sold it to the Egyptians at a huge profit. Strabo relates in his Geography that the lake contained large amounts of bitumen, which would float up from the depths along with bubbling water. The information given by Pliny the Elder and Isidore of Seville concerning the bitumen from the Dead Sea has been reiterated in all the medieval treatises on natural history. The Assyrians, Phoenicians and Egyptians are known to have used bitumen extensively as a waterproofing agent in construction and shipbuilding. Moreover, the Egyptians used it in mummification: the Persian word mumiya itself means bitumen or tar. The medicinal properties of “Jewish bitumen” are described in a treatise by the well-known Arab scientist Avicenna.20

The significance of bitumen crosses

Archaeological finds of objects made of hydrocarbons brought from distant lands are exceptionally rare. Moreover, it is very difficult for archaeologists to determine the origin of such materials. A good example of scrupulous collaborative research is the analysis of pieces of bitumen from the well-known 7th-century royal burial mound with a boat burial at Sutton Hoo (England), which demonstrated that these samples belong to the Dead Sea family of bitumen. Accordingly, along with many other finds from the burial site–textiles from the Levant, a vessel from Egypt and table silver from Byzantium–the bitumen represented a prestigious item of luxury brought from afar.21 Much more intensive contacts between Europe and the Near East developed in the time of the Crusades. Knights and pilgrims returned from the distant lands could describe not only the sacred sites they had visited, but other wonders of the east as well, including the uses and natural forms of hydrocarbons: burning fountains and Greek fire.21 Of course, in those days nobody saw the connection between a small item of bitumen that had been brought back and the lethal invention of Greek engineers or the fountains of oil. A cross of “Jewish bitumen” constituted a sacred and magical relic from the Dead Sea of Biblical fame.

2Musin AE (1999) Archeology of the ancient Russian pilgrimage to the Holy Land in the 12th-15th centuries. Theological Works No. 35: to the 150th anniversary of the Russian Ecclesiastical Mission in Jerusalem (1847-1997), Russia, pp. 96; Musin AE (2009) Pilgrimage in Ancient Russia: historical concepts and archaeological realities. In: Belyaev L (Ed). Archeologica Avraamica: research in archeology and the artistic tradition of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, Indrik, Russia, pp. 244; Musin AE (2010) Church and townspeople of medieval Pskov. Historical and archaeological research, Faculty of Philology and Arts, St. Petersburg State University, Russia, pp. 223; Musin A (2010) Russian Medieval Culture as an "Area of Preservation" of the Byzantine Civilization. In: Grotowski P Ł, Skrzyniarz S (Eds). Series Byzantina. Studies on Byzantine and Post-Byzantine Art, No. 8. Towards rewriting? New Approaches to Byzantine Archaeology and Art. Proceedings of the Symposium on Byzantine Art and Archaeology Cracow, september 8-10, 2008, Polish Society of Oriental Art, Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński University, Jagiellonian University, Pontifical University of John Paul II in Cracow, Poland, pp. 20, 22.

3Pavlenko SV (2006) Manufacturing of beads, crosses and images from pyrophyllite shale in specialized settlements of the medieval Ovruchsky volost. Slavic-Russian jewelry business and its origins. International scientific conference dedicated to the 100th anniversary of the birth of Gali Fedorovna Korzukhina. Abstracts St. Petersburg, April 10-15, 2006, Publishing House of SPbI RAS "Nestor-History", Russia, pp. 146; Pavlenko SV (2008) Studies of ancient Russian special settlements on the processing of pyrophyllite shale (based on the example of the settlement Pribytki-I). In: Makarov NA, Chernov SZ (Eds) Rural Russia in the IX-XVI centuries: a collection of articles, Science, Russia, pp. 249.

The advent of Christianity in the East Baltic brought the population new opportunities in the sphere of religious life. They became part of the pilgrimage movement, which encompassed the whole of Europe at the time and included travel to the Holy Land. The subject of distant pilgrimages is, as yet, quite a novel theme in the research literature in Latvia. Accordingly, crosses made from materials not available in the East Baltic, such as mother-of-pearl and bitumen; represent the most vivid archaeological evidence of trips to the Biblical sites.

The examination of mother-of-pearl crosses from present-day Latvia has shown that this is not a homogeneous group in terms of form and dating of the objects. In terms of their form, the crosses covered in the article may be divided into two groups. The early finds, from the 13th century, recovered in Riga and Turaida and depicting the Kouvouklion of the Tomb of Christ, are pilgrims’ souvenirs from the Latin States of Palestine. On the other hand, the context of the Cēsis cross recalls the tragic events of the Livonian War. This find indicates the significant role of items of personal piety among the Russian soldiers. The Cyrillic inscription raises the question of its manufacture outside of the Holy Land–for example at Athos, Bulgaria, or in Russia itself, using imported material. Among Ancient Russian archaeological finds there are many crosses made from different kinds of rock: amber, limestone, grey slate, crocoite, steatite, jasper, lazurite and marble. Because of the crosses from Riga, a further group can potentially be identified–crosses of bitumen, relating to distant pilgrimages and originating from the Holy Land. In order to confirm or reject this idea, there is a need to identify pieces made from bitumen among the stone crosses of Ancient Russia and to continue investigation of the hydrocarbon material that the crosses are made of. Starting from the 17th century, when medieval symbolism was beginning to disappear, mother-of-pearl became extremely popular and in addition to a variety of religious items, such objects as mother-of-pearl buttons and jewellery also became widespread in Europe, along with a great variety of everyday items inlaid with mother-of-pearl: tobacco boxes, weapons, fans, furniture and so on. On the other hand, the use of bitumen for similar kinds of small items or in jewellery did not see further development and the bitumen crosses discussed here remained as a minor detail in the historical mosaic of the Crusades.

None.

Author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

©2018 Spirgis. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.