Journal of

eISSN: 2573-2897

Review Article Volume 7 Issue 2

1Doctor in Social Sciences, Archaeologist, Profesor and Researcher at the School of Anthropology of the University of Costa Rica, Costa Rica

2Magister Scientiae in Anthropology and Archeology, Professor and Researcher at the School of Anthropology of the University of Costa Rica, Costa Rica

Correspondence: Jeffrey Peytrequin Gomez, Doctor in Social Sciences, Archaeologist, Professor and Researcher at the School of Anthropology of the University of Costa Rica, Costa Rica

Received: August 04, 2022 | Published: August 12, 2022

Citation: Gomez JP, Bonilla MA. Abangares, Guanacaste. mining production as an example of industrial archeology in Costa Rica. J His Arch & Anthropol Sci. 2022;7(2):61-65 DOI: 10.15406/jhaas.2022.07.00256

This article focuses on the investigative potential of the contexts associated with a case of gold extraction developed in Costa Rica by a transnational during the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The intensity with which the ore was extracted from the Abangares mountain range, as well as the state-of-the-art technology at the time, which is present in a large part of the mines called Tres Amigos and Tres Hermanos (La Sierra district); makes this place an optimal space for the development of anthropological, archaeological and historical research. However, to start we will focus on the evidence found on the property of the Ecomuseo de Las Minas de Abangares, an instance directed by the local government (municipality).

Several of the material remnants of this mining production are found "in situ" and with part of them the Ecomuseum of Las Minas de Abangares was created, which has a declaration of "Historic Architectural Monument" according to Law 7555 of Costa Rica. The foregoing constitutes one of the first declarations of an asset as industrial architectural heritage in the country (declared in 2001) and that offers possibilities for future research, conservation and dissemination in Costa Rica of these contexts.

Keywords: Abangares, industrial archaeology, mining, gold, material culture

In Abangares, province of Guanacaste in the Costa Rican North Pacific (see Figure 1), mining production has not only modified the mountains, but also the way in which people have settled and linked to the production process of gold extraction.

This place was occupied since pre-Columbian times, however, the objects that were then made of gold arrived via transaction and came mainly from the South Pacific (South of Costa Rica, Northwest of Panama) and were made from "river gold". The exploitation of this resource in the North of the country during the pre-Columbian period is not known, so the local sources of this metal were not exploited until the end of the 19th century.

In the 19th century, a migration of inhabitants from the Central Valley of Costa Rica originated towards this locality, here places such as San Ramón, Poás and Atenas (province of Alajuela) stand out. Between the years of 1880 and 1900 there were two important factors that attracted migratory currents to the area; precisely one of them was the opening of the industrial extraction of the Abangares mines and the other the bitter cedar forests, activities that required a large amount of labor to exploit them.1,2

Historical context: During the 19th century and after independence, liberal governments sought to develop the vast territories outside the Central Valley (the most populated area at the time) and thus provided incentives for the "colonization of vacant land" (many of them were historical territories where indigenous populations could even continue to live and remote places whose access was limited due to the low investment and number of communication routes). The objective was for people to “open the way” and, at the same time, put the “idle” land into production, this focusing -mostly- on the agriculture of coffee, a monoculture that was exported through the port of Puntarenas in Costa Rica’s Central Pacific. This general environment led to the granting of concessions to transnationals in order for them to carry out road, rail and port infrastructure works in the Caribbean; which facilitated the exit of the coffee that was exported to Europe and North America.

In this context, several concessions are offered in different parts of the country, some for the production of agriculture and livestock, among them to Germans in La Angostura (Central-Caribbean sector) or to Italians in San Vito (South Pacific), among others; as well as concessions for the construction of railway lines that would cross the country and, in this way, lower the cost of exporting coffee (since it could be sent through the Caribbean, province of Limón).

This is how foreign capital entered and in the 19th century -through several negotiations- the concession of land to Mynor Cooper Keith and companies linked to him in the Caribbean area (Central, South and North) and later in Abangares. (North Pacific), subsequently at the beginning of the 20th century also in the Central and South Pacific; Abangares being used by them for mining extraction, unlike the other places mentioned, where bananas have been produced for almost a century (and in some sectors still today).1

It is necessary to clarify that during the colonial era in Costa Rica, mining extraction was not practiced, so the first incursions in this diligence were concentrated between 1821 and the 1840s, being the first mines (the Montes del Aguacate) discovered in a casual way. As Carolyne Hall (1972) points out:3

Despite the frustrated efforts in the colonial period to discover any kind of precious minerals, it seems that immediately after Independence, it was mining and not agriculture that became the main resource of the new Republic, the exploitation of the Montes del Aguacate between San José and the Pacific coast and in which the English miners were the promoters and achieved greater benefits, despite the fact that they could only extract a few million pesos. (p.30)

However, it is known that said exploitation -in the Monte del Aguacate- was carried out with a rather precarious technology, which did not allow it to generate a large amount of resources; this unlike the one implemented for the hills in Abangares in later years.

It will be until the 1860s when there is greater interest in the development of mining activity in Costa Rica, due to the fact that some local businessmen invest capital. For example, in San Ramón de Alajuela “(…) 23 veins are reported to work various minerals such as silver, gold, coal and quicksilver. Also in Esparza, Puntarenas and Atenas, there were around 19 mining complaints [denuncios] from individuals who, in turn, carried out different economic activities”.2

Mining and transnational companies: In Abangares the history of gold exploitation began in 1884 when Juan Alvarado Acosta discovered a mine, which he sold in 1887 to the brothers Vicente, Paulino and Rafael Acosta; who baptized it as "Three Brothers". Two years later, this mine was sold to the Anglo American Exploration Development Company Limited, during the government of Rafael Iglesias, and later passed into the hands of Abangares Gold Fields; where Minor C. Keith was one of his main associates.1,2,4

After obtaining the mine by said transnational mining exploration begins and new mines are created throughout the mountain range of the Sierra de Tilarán in Abangares territories. Exploitation techniques were imported that increased the productivity of gold processing. The application of cyanide, mercury and the spraying of gold-bearing material with complex machinery such as breakers or mallet boxes, filters, mills, air compressors, locomotives, lifts; determined the great development of the area (which is compared to the development that caused the gold rush in California) so much so that by the time of 1901, there was a commissariat (small market), hospital, shops, hotels, workshops, factory of ice, telegraph and an electrical substation.4

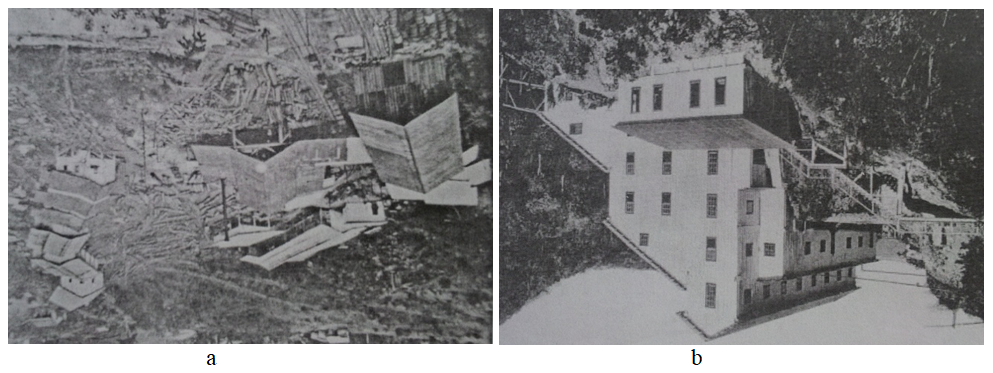

This mining development, according to Castillo (2009) and Calvo (2011),2,4 caused a significant flow of immigrants from different places, both within the country and throughout Central America. As an example: Italians who were brought as stonemasons to make the foundations of the Los Mazos Building (place where the gold was processed, (see Figure 2); Jamaicans, who had already carried out work with the transnationals in the construction of the railway and who served as foremen (in better working conditions than the others due to their command of the English language); Germans, English and North Americans who developed administrative and technical tasks. In the case of the Chinese, due to racist policies, they were unable to successfully enter the labor market, but they are the ones who are going to develop a strong services sector linked to commerce in the main population centers.

Figure 2 Abangares mining infrastructure at the beginning of the 20th century.

a: Sawmill of La Sierra. George Sloan Watson Archive. Abangares Mining Ecomuseum; b: Los Mazos Building, La Sierra. Fernando Zamora. Album of views of Costa Rica, both from the beginning of the 20th century(Castlillo, 2009, p. 164).

It is due to the above that for this location (politically denominates as “cantón”) of Guanacaste, Abangares, most of the mining evidence is concentrated in the Sierra district, which derives from the mountain range that crosses the territory. The head of the “cantón” is called Las Juntas, whose name has a very particular etymology: “The old miners say that after payday they met in the nearest town to drink liquor and play poker and this activity was called 'Las Juntas '”.4

On the extractive practice of gold and related material culture: As already indicated, it was the transnationals who, at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, dedicated themselves to building a large amount of infrastructure for the exploitation of minerals from the mountains, including: railway lines, the house (or building) of Los Mazos, the tunnels, the installation of electrical current (including inside the tunnels), the cellars for gunpowder, among other buildings. All of the above to facilitate the extraction of gold from the rocky matrix, also for this purpose they used cyanide; causing contamination in the area since the beginning of the mining activity. As time went by, various companies exploited the gold resource in the area until the 1990s, at which point they declared bankruptcy and left the country.1,2

It is precisely the footprint of this industrial production that can be found distributed -even today- for several kilometers in the middle of various properties in the area. Although it is necessary to clarify that it is not complete, since some materials have been reused, for example, part of the Los Mazos building was transferred to Turrialba, in the province of Cartago (Antonio Castillo, historian, personal communication, 2013), and now constitutes sections of the infrastructure of a mill; as well as some rails of Abangares were used by the neighbors both in the structures of their houses and in gates, bridges, etc.

On the importance of scientific work with industrial evidence and the Las Minas de Abangares Ecomuseum: For many decades, the “canton” of Abangares was the most important mining enclave in Costa Rica, starting mining activities there around 1885 and culminating -exploitation by transnationals- until the 1990s.1 In this area there was a development both in infrastructure, previously mentioned, and in trade and the services sector; this due to the influx of large numbers of immigrants from other regions of the country, as well as several foreigners.4

Despite this, in Costa Rica most people are unaware that there is intensive mining production from the 19th century to the present, including - at the national level - few are aware of places of tourist visitation linked to said production, as it is the Ecomuseum of the Mines of Abangares; which was created in 1991 and is located precisely where the gold processing plant used to be. This museum seeks to rescue part of the buildings and the machinery that was used in the era of greatest development and mining exploitation.

In total, the Ecomuseum has 38 hectares and belongs to the Municipality of Abangares. It offers an exhibition (in the open air) of machinery related to the mining, a room with photographs of the time when mining production was taking place and a room (or small museum) with objects typical of the production process such as: crucibles, carbon, pulleys, an oven, saws, bottles, household implements, tools of various functions, vehicles or their remains, etc.

Likewise, the Ecomuseum has immovable property, among them the stone bases carved by Italians and that constitute the foundations of the Los Mazos building; where up to 100 tons of gold-bearing material was ground daily for 30 years. At the same time, in its surroundings there is a dynamo or pelton that was used in the hydroelectric plant, as well as an air shovel or wagon loader and one of the steam railway machines called "La Tulita" (see Figure 3); this in honor of the wife of the administrator of the mines in 1904 (Kimberly Guadamuz, in charge of the Ecomuseo Las Minas de Abangares, personal communication, 2012).

Figure 3 Las Minas de Abangares Ecomuseum.

a: Ecomuseum Hall; b: “La Tulita”, Photographs Mónica Aguilar, 2013.

The inventory of industrial archeology in Abangares: The work carried out in the Abangares Mines Ecomuseum consisted -mainly- of several archaeological reconnaissance visits, by the authors, in order to identify the appropriate places to concentrate on data collection; as well as inquiring into the museum's own registry to find out if the goods had a previous and adequate cataloging, in addition to knowing the possible information gaps.

At the same time and as mentioned in another paper related to the National Inventory of industrial goods in Costa Rica,5 for the actions pointed out in Abangares, it had the collaboration of a group of students from the course AT-1159 (Industrial Archaeology) that was taught in the second semester of 2013 at the University of Costa Rica. The latter were the ones in charge of inventorying part of the collection of goods present there, both in the hall itself and in some sectors on the grounds of the Ecomuseum property.

The work in the place was organized in three subgroups located in different altitudinal floors, the first directly in the Ecomuseum facilities; the second in the vicinity of it and up to the fourth floor of the Los Mazos building; and the third in the last 3 floors of said building and around it.

In the case of the work carried out in the room where the artifacts are deposited for the exhibition (“museum”), this place has an organization according to the following categories cited by Monge et al.6:

For its registration, then, this same ordering was followed; the first and fundamental task being the recording of the information in accordance with -and in- the inventory sheet built specifically for these purposes.6

This working subgroup managed to report more than 190 artifacts distributed in the various categories indicated. At the mining level, several materials were identified from the Gyanide Supply Co. 56 New Broad Street London factory, which sold certain supplies to be used in the mines, such as cyanide, arsenic and chemical products used to treat rocks and extract gold.6

Another material correlate in Abangares of these international relations, imports and globalized production and characteristics of these times, is the presence of an EPP NCR_reve (t/L) and SGDG 20275 watch (see Figure 4), which was manufactured by the National Manufacturing Company in Dayton, Ohio; company that specialized in producing and selling the first cash register, invented in 1879 by James Ritty. In 1884 the company and its patents were purchased by John Henry Patterson and its name was changed to the National Cash Register Company. On the other hand, of the canfin or kerosene lamps, the only one that could be identified in the Ecomuseum sample was the Butterfly trade Mark.6

Figure 4 EPP clock NCR_reve (t/L) and SGDG 20275.

Manufactured by the National Manufacturing Company in Dayton, Ohio.6

Photography: Monge et al., 2013; edited by Marco Arce 2015.

The tasks carried out in the immediate vicinity and up to the 4th floor of the Los Mazos building revealed porcelain objects and others, which were linked to the electrification of the building. For the bases of this building (both the carved stones and the supports on which the large machines rested) it was recorded that they were made with stones (river stones) and cement; protruding from them some thick iron screws with their respective joints.

The evidence varies depending on the floor of the Los Mazos building, due to the fact that in each of these there was a specialization (a specific part) of the gold production chain, handling the heaviest actions, such as grinding rocks, on the upper floors; while in the lower ones the ore was increasingly processed until it ended up in the form of ingots. In addition to the descriptions of the building, we proceeded with the floor plan survey -floor by floor- of this structure.7

However, in the surroundings (between the museum and the Los Mazos building) larger objects and in a better state of conservation were recorded, mainly machinery. Among them we have: small wagons to transport rocks from the mines (see Figure 5), a box of hammers to crush rocks and whose inscription indicates that its origin is from San Francisco, California, of the Company Union Iron Works; large wheels that were used to raise and lower miners' tools or to move the miners themselves (but later as part of a mill). Another example is an air compressor in good condition, with which holes were opened in the mines (pressure air was injected) and it was also used to ventilate the interior of the mine tunnels Kimberly Guadamuz, in charge of the Las Minas de Abangares Ecomuseum, personal communication, 2013.7

Figure 5 Views of the Las Minas de Abangares Ecomuseum

a: Lower part of the Ecomuseum; b: Los Mazos Building Sector; c: High part. Photographs Monica Aguilar, 2013.

In this sector, too, there is a pellet of electricity that is in the back part of the museum; which was in charge of moving the turbines to produce electricity by means of hydraulic force. Some of these goods were made by the Pacific Gold Mining, among them: flat, half-round, round, dotted files; machine locks, horns, saws; steel rods; saws with accessories; iron screws; potash; mineral oil; iron and steel tools (ANCR, 1892).7

On the other hand, the work carried out in the highest sector of the Ecomuseum property provided information of various kinds about the mining locomotive ("the Tulita") and the stones used in this mining trade, which were brought from Australia (due to their great hardness and to serve as part of the abrasive that was placed inside the mallet boxes); as well as with respect to different machinery, car engines, artifacts related to the electrification of the tunnels and items of daily use of the miners such as plates, among others.

Among the machinery evidence, information was recovered from an Elmco Model 12b “Rocker Shovel” excavator, whose production dates back to the 1930s; a stationary motorcycle and deck boxes manufactured by Edward P Allis & Co. of Milwaukee. Although specifically the machines present in the Ecomuseum come from this same company, they were manufactured in Chicago.8

1A clarification is made, the mining activity in Abangares continues in force these days, however; it is of an artisanal nature (not at an industrial level).

The inventory work on industrial archeology developed in Abangares has been fruitful, these in terms of quantity and diversity of information collected. In short, it was possible to inventory more than 250 materials from large-format machinery to screws, nails and various metal sheets that were part of the mining infrastructure; as well as the lifting of plans (maps) of the various floors of the Los Mazos building.

At the level of temporality, materials that were mainly manufactured between 1880 and 1950 are observed; which coincides, directly, with the time of greatest mineral extraction in this place.

The inventory record was put to the test, several adjustments were made and, although much remains to be inventoried, it is necessary to locate other fundamental contexts related to the mining activity of the place. For example, we have to locate the ancient settlements (one located in the upper part of the mountains and close to the mines) and carry out their scientific excavation; apart from the study of the context in which several mine workers were buried, this after a strike and revolt that took place at the end of the 19th century, as well as registering more infrastructure that is in private hands and properties, some of which already were visited by the authors.

Although at the beginning it is based on the material culture, the inventory and the maps made are conceived as a very preliminary work. In this sense, it is necessary to complete them and, above all, value the history of these sites. We need to collect the stories and memories of Abangares related to mining, not only those that contemplate the magnificence of the productive and organizational boom (by the enclave), but also; those that tell us about the daily life of the miner and his life in this community.

All these data will be essential to be able to return that information to the locals, thus strengthening the identity of the Abangareños. In addition, it should be taken advantage of the fact that this place is open to public visitation (the Ecomuseum) and the importance that this research situation can enhance for the general visibility of industrial archeology in Costa Rica.

Together with the above, being able to develop this first stage of the research with a group of advanced archeology students allowed us to assess an industrial archaeological heritage that, together with the "historical" or that associated with the colonial era, is little addressed in the country. .

Thanks

To the Municipality of Abangares for allowing the research to be carried out at the Ecomuseo Las Minas de Abangares, mainly to Ms. Kimberly Guadamuz, in charge of said museum and who is always willing to collaborate.

To the archaeologist Marcos Arce Cerdas who collaborated with the images.

To the archeology group of course AT-1159: Alberto Aguilar, Luis Angulo, Yamileth Angulo, Keller Araya, Ricardo Chacón, Ignacio Díaz, Alejandro Cambronero, Andrés Esquivel, Jonathan Herrera, Cindy Monge, Diego Montero, Gueisy Mora, Natalia Pacheco, Estefanny Ramírez, Sofía Ramírez and Josebec Ureña.

To the historian Antonio Castillo for his support.

None.

None.

©2022 Gomez, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.