Journal of

eISSN: 2573-2897

Research Article Volume 3 Issue 1

VSEGEI Geological Research Institute, Russia

Correspondence: Yury S Lyakhnitsky, VSEGEI Geological Research Institute, Russia

Received: October 30, 2017 | Published: February 21, 2018

Citation: Lyakhnitsky YS. Conservation of paleolithic cave art in the Capova cave. J His Arch & Anthropol Sci. 2018;3(1):137-141. DOI: 10.15406/jhaas.2018.03.00075

The Kapova Cave (Shulgan Tash) is located in Bashkortostan, the Southern Urals, in the Shulgan Tash Reserve. This is the only cave in Eastern Europe, where Paleolithic drawings of about 19,000 years old are preserved. To date, about 200 images are known in the cave including realistic zoomorphic drawings, abstract geometric figures and ochre spots. The paper is devoted to the conservation of ancient drawings and their peculiar features. The cave art resembles West European analogues, but it has specific features. This suggests the existence of a kind of a center of ancient culture in the Southern Urals in the Paleolithic.

Keywords: south urals, paleolithic cave art, conservation of drawings, peculiar features of the paleolithic cave art

Kapova Cave (Shulgan-Tash) is located in Bashkortostan, the Southern Urals, in the Shulgan Tash Reserve on the Belaya River. Its coordinates are 53°02' N; 57°03' W. It is a large karst three-level system of chambers, galleries and wells having the total length of 3323 m with vertical amplitude of 165 m. The karst system is characterized by large chambers and galleries, great dynamics of microclimatic and hydrological processes. This fact distinguishes it from most of West European caves with well-preserved artworks. Some of the drawings were badly damaged or turned into vague spots of red ochre due to negative environmental factors. VA Ryumin1 the biologist of the reserve,1 discovered Paleolithic drawings in the Kapova Cave in 1959. This is the only cave in East Europe with quite a few well-preserved Paleolithic drawings. The age of the drawings is about 19,000 years. Our group of the Russian Geological Research Institute (VSEGEI) with the support of speleologists from the Russian Geographical Society (RGO) carries out comprehensive monitoring of the karst system for more than 20 years.2,3 In addition, we completed the fixation of its Paleolithic paintings and in 2013 published the “Catalogue of Drawings and Symbols of the Shulgan-Tash (Kapova) Cave”.4 Now about 200 drawings are known in the cave. Archeology of the cave was studied by archaeologist ОN Bader5,6 and later by VE Shchelinsky,7 who uncovered an Upper Paleolithic cultural layer.7

Fixation of the kapova cave paleolithic drawings

The unique Paleolithic art of the Kapova Cave is of great cultural significance, as a phenomenon of creativity of our primogenitors. Unfortunately, environmental conditions have been unconducive for its preservation. Therefore, we take measures aimed at improving microclimatic and hydrological conditions. In summer, screens are installed to reduce the thermal and humid influence of weather outside on the interior of the cave. Shakeholes in the canyon were plugged back on the surface to reduce the inflow of karst infiltration water into the cave. Despite the measures taken, slow degradation of painting takes place. Therefore, it is very important to fix the drawings using integrated approach and preserve them for future researchers. The approach includes photo fixation, topographic tying-in to morphological elements of the cave, morphometry and computer image processing.

Photo fixation of cave images is quite a challenge. Oleg Minnikov and Anton Yushko from PGO took part in the work. They used modern Nikon D-3 and Nikon-700 cameras. We have developed a special shooting technique.4 There were problems with lighting the images. The light should be sufficiently bright, homogeneous and close in spectral characteristics to the solar one. Electronic flashes, halogen illuminators with bright white light, and diode lighters were used as well as the black-and-white standard “Kodak Gray Scale” and other color standards. When processing the images taken with different illumination, it was possible to obtain almost identical images with a true color similar to the solar one. In recent years, we only use diode lighters for photographing to ensure better preservation of drawings. In addition to fixing the image, it is necessary to show peculiar features of the substrate, relief: surface roughness, cracks, chips, etc. For this purpose, lateral, inclined light is used, emphasizing all the peculiarities of the wall surface. For more detailed recording the images and features of those parts of the wall on which they were applied, stereoscopic photography was used. Particularly good results have been obtained when taking photos with the Sputnik stereocamera using wide (6 cm) slide film.

In photo fixation, it is not enough to show only the image, it is also necessary to capture the interior of the cavities in which it is located. For this purpose, various types of shooting the walls were used. All the walls of the chambers with drawings were shot including circular panoramas, when the whole interior of the chamber is covered to a height of about 10-15 meters. Topographic tying-in the images involved the creation of grid coordinates system along the walls with drawings and the binding of their axes to the plans of the chambers. Morphometry of the drawings included measurements of dimensions of the drawings and their main elements. Besides, colour standards had the millimeter scale, which allowed to judge drawing dimensions.

The images were processed in digital form using special programs that allowed obtaining more saturated and contrast colours similar to primary one while maintaining the appearance of the wall. The fact is that for many thousands of years, the drawings have been subjected to negative environmental factors and have been significantly spoiled. They became much paler, less contrasting and became almost monochrome. Their primary appearance, perhaps, was polychrome. This is evidenced by the discovery of a composition “Little Horses of the Chamber of Chaos”, which was found under the layer of calcite cores and retained its primary bright polychrome appearance.

Peculiarities of paleolithic artworks in the kapova cave

The collected materials allowed grouping the images and deduce preliminary inferences about their relative age. Drawings of the Kapova cave form several groups presumably of different ages based on a set of symbols and their location in certain chambers. They are executed in slightly different styles, in accordance with traditions and perception of environment prevailing at the time of their creation. These differences, perhaps, can be explained by the functional purpose of the images, the canon of their placement in the cave sanctuary. The most realistic red contour images of the chamber of drawings on the second level are well-preserved and best known (Figure 1). They are dominated by mammoths (7 drawings); there are woolly rhinoceroses (2), little horses (2), one buffalo and two schematic anthropomorphic images. Almost all these drawings are contoured and only one, the Red Mammoth, is a silhouette; it is completely painted in red with ochre. The colour of these drawings is practically scarlet, the intensity of the dye is not uniform; it is medium to low. All the images of the Chamber of Drawings are zoomorphic and executed in a single style, as if following a certain canon. In each composition, there is one anthropomorphic schematic drawing. It is of interest that the anthropomorphic image on the eastern wall is drawn in front of the mammoth, next to it. This is not a hunting scene. In the chamber, there is only one geometric symbol a large trapezium with twelve inner ribs located in the lower right corner of the first composition. This is undoubtedly a single formational group of drawings closest to the West European Magdalenian or Solutrean epoch. According to the classification of Leroi-Gourhan, it refers to the transitional group, between the third and fourth ones. Age of the charcoal from the O.N. Bader’s pit under the eastern wall of the chamber uncovered by Tatiana Shcherbakova, is 17,000 to 19,000 years according to results of the VSEGEI laboratory. This is the Upper Paleolithic VE Shchelinsky also obtained the Paleolithic age of the cultural layer.7 It is important that in the cultural layer he found a fragment of limestone with a drawing (sketch) and ochre. This fact suggests that the age of painting is similar to the age of the cultural layer.

Figure 1Composition No. 1 on the eastern wall of the Chamber of Drawings. These drawings are apparently most ancient in the cave.

Realistic red partially polychrome drawings with well-defined styling elements accompanied by at least two trapezia can be assigned to the second group. This group includes Little Horses of the Chamber of Chaos (Figure 2) and Bison from the Chamber of Symbols. There are no mammoths among the animals. The stylization of the drawings is expressed in the elongation of the horse noses, distortion in the contour of the upper little horse silhouette, the sharp unnatural bending of its tail and the exaggeratedly voluminous mane. Trapezia are drawn geometrically clearly and differ in the number of ribs and internal features of the structure. A new symbol appeared a one-sided curved Ladder above the Upper Little Horse. In 2018, an experienced restorer from Andorra, Edual Guillaume, revealed in this composition a very interesting realistic drawing of a camel. First poorly preserved schematic image of a camel was identified by our group in 2008. It is important to note that Paleolithic images of camels have not been found before in caves anywhere in the world. These compositions are located on the first level of the cave, at the entrance to the Chamber of Symbols and into the Chamber of Chaos. This is the continuation of the ancient tradition with the observance and development of its canons. The age of the drawings of this group is supposedly the latest Paleolithic.

Figure 2 The composition Little Horses in the Chamber of Chaos on the first level of the cave. In this composition, the camel was first identified.

The third group of images is characterized by small stylized and formalized, rather primitive zoomorphic images (Figure 3) and the lack of traditional trapezia. Instead, various new symbols appear: U-shaped, radial, circular, trapezium derivatives, etc. In this case, there is no connection of zoomorphic drawings with symbols. Perhaps they belong to groups having different age. They are characterized by poor preservation, lack of painting details, static figures of animals. All of them are located in the Dome Chamber and in the Chamber of Symbols on the first level. Typical zoomorphic drawings of this group are Little Red Horse, Last Mammoth, Dragon, New Mammoth and, possibly, ibex (Argali).

Figure 3 Example of drawings of the third group – the New Mammoth. Static sketch. Its zoomorphic image was identified in the course of computer image processing.

cThe fourth group of images is a variety of red geometric symbols located on the ceiling of a low flattened cavity under the eastern wall of the Chamber of Chaos. Similar symbols have not been seen before. Among them, there are very complex derivatives of trapezia (Compound Trapezium) (Figure 4), original (Tower and Dagger), compound, consisting of several elements (forked sticks with line segments). In general, the group is characterized by abstract patterns. It is based on a completely new concept as compared to the previous one, although some rare details have passed from old symbols of previous groups. For example, double “earlets” on some compound symbols. Perhaps, this group of images was created in the post-Palaeolithic time.

Figure 4 Compound trapezium, an example of compound geometric symbols of the fourth group, a derivative of traditional trapezia.

The fifth group of images is conditional since the authenticity of the drawings has not yet been proved. They are black charcoal archaic drawings, with features of primitivism, which are located only in the Chamber of Drawings on the second level. An example is the Black Mammoth (Figure 5) and the Little Black Horse. If their authenticity is proven, it can be assumed that they are the oldest drawings in the cave. According to Leroi-Gourhan, they belong to the first or second group. The sixth group includes numerous dots. They are symbols that indicate various items in the cave. Among them the Acoustic Point (Figure 6), Pale Triangle, and the Hidden Symbol above the stone sack near the northern wall of the Chamber of Chaos. The Acoustic Point indicates a place in the cave, where acoustic effects echo and reverberation are particularly well heard. Numerous dots can be seen on the southwestern walls of the Dome Chamber and the Chamber of Chaos.

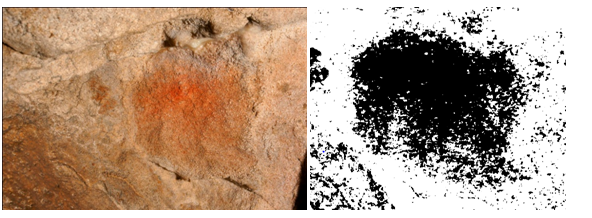

Besides, there are many blurry red spots in the cave (Figure 7). Their nature is identified in the course of computer deciphering. Some of them turned out to be relics of drawings. Sometimes, it is even possible to restore partially their initial image. Others are possibly natural spots of iron oxides. This classification is based on a set of features. The materials obtained in the course of image fixation allowed the authors to draw a number of conclusions, and to make several suppositions. In his monograph, OH Bader put forward the idea of a considerably high degree of similarity between the Shulgan Tash (Kapova) cave art and West European analogues. We presume that there are notable differences between them, too. The concept of creating the earliest compositions as well as many drawings and symbols in the Kapova Cave are quite peculiar and by right can be considered featuring distinctive identity, although being a part of the global Paleolithic culture.

Figure 7 Spot on the northern wall of the Chamber of Symbols. The authors failed to restore its initial image.

First of all, this relates to the conceptual discrepancies between the first group of drawings (in the Chamber of Drawings) and Magdalenian or Solutrean analogues in West Europe. The first composition on the eastern wall of the Chamber of Drawings (Figure 1) is a solemn procession of animals, embodying some groups of people’s totems. The animals are orderly positioned and linked together due to the composition. All the animals are in the process of walking along the hall perimeter from right to left, except one. That is a lonely Walking Mammoth ahead of them, a dynamic, well-drawn figure. The other animals moving some distance behind it form a large wedge with Big Horse at its apex. Behind and above it there is Big Mammoth, below it there is Big Rhinoceros. In the background, separated by a vertical gutter, there are some animals forming the second train: a little horse, a mammoth and a baby mammoth. Perhaps this procession, walking through the space of the hall towards the sun, represents the life cycle of the Universe. Walking mammoth holding aloof is depicted with its head turned to the horse on its right upwards and seems to be drawing viewers’ attention to it. The scene produces the impression of being a solemn procession. This is not just artwork; it is an esoteric story, made up in accordance with a certain canon. The second composition on the western wall in the Chamber of Drawings is distinguished by lack of solemnity and convention in the arrangement of the figures (Figure 1). The mammoths are walking across a hilly plain, which is formed by the wall with oval niches, some distance ahead of them there is Buffalo. Next to Central Mammoth, there is a small figure of a running man. It is very likely to be a scene from everyday life, made with consideration of unity in composition and the same stylistic devices. It is notable that the animal images are not simply fit in the wall relief. Rather, the relief itself was responsible for their position and the inner structure. The master took advantage of it in order to achieve the greatest possible expressiveness. The wall is large enough to place many figures, but only four were drawn. They are all oriented from right to left. When compared with West European cave drawings, at first, these compositions seem to be much more primitive, but being given a thorough thought and in-depth comprehension, they appear to have been conceived in a quite different way. Different approaches to creativity account for differences between West European multi-figurative masterpieces of art and the compositions from the Kapova Cave. In the Kapova Cave the artist hardly tried to render the external beauty of animals, rather it was an attempt to create their images, to convey inward solemnity of the moment when people meet with higher powers. This is a kind of Paleolithic "altar", rather than an art gallery. A certain canon and conventionality in images are hence observed. Perhaps it is appropriate to draw a similarity between them and masterpieces of art in Vatican, as well as the "Holy Trinity" icon by Rublev. Perhaps the people who created paintings in Western Europe and the Urals, thought differently and felt differently. In one situation, artistic aesthetic impulse prevailed, in the other situation it was an urge to reveal spiritual potential. The symbols differ significantly. In the West, they are simple rectangular lattices that are not associated with zoomorphic images, a variety of ovals, lines, etc. Whereas specific trapezia with hanging "earlets" predominate in the Kapova cave upper corners (Figure 8). They are naturally associated with zoomorphic images and have a different number of internal sub vertical ribs. Thus, there appears to be a distinct system. The other, apparently later symbols are no longer associated with the drawings and form clusters away from them. Unfortunately, we simply do not understand the language of these symbols. Among them, there are certainly petroglyphs-symbols and petroglyphs conveying information (predecessors of hieroglyphs). People might well have been longing to pass information. At that time, people already made attempts to create calendars.8 There exist some hypotheses interpreting ancient drawings as a kind of a map of the area.9 Perhaps they tried to invent numerical symbols. We do not find the traditional view, according to which all petroglyphs are considered male or female, quite right. Even at that time, people were more spiritually mature, their creativity could not only reflect their sexual impulses and it could also reflect their needs in spiritual and intellectual life.

Figure 8 Geometrical abstract symbols that occur in the cave. There are trapezia with variable number of ribs typical of the Kapova Cave.

Traditional trapezia in the Kapova Cave are of great interest (Figure 9). They are beautiful, geometrically perfect figures. They might have appeared as a development of the female triangle, as well as an abstract model of an animal with a short earlet a head and a long tail. Options that are more utilitarian are also possible: a basket, a bowl, a hut. It is noteworthy that they always accompany the drawings of animals, often located below and to the right of the animal. It is logical to assume that trapezia are certain determinants informationally complementing totem images. Since there is always different number of ribs in the trapezia, one can make a logical assumption that the trapezia are numerical symbols that somehow characterized zoomorphic totem drawings.

From our point of view a variety of the drawings’ stylistic features, alterations in the traditions of symbols, their morphological diversity, accompanied by changes of sites constitute convincing evidence that the Kapova cave was used as a sanctuary for a long time. Apparently, the images were created over many thousands of years, rather than within one epoch. Unfortunately, this is not proved by age definitions of the drawings yet. Characteristic of the Kapova cave is the absence of palimpsests (later images superimposed on effaced earlier images), whereas in the West this is a common phenomenon. There are finishing paintings, though. There are cases that can be interpreted as ritualistic destruction of earlier images. The red bright spot, resembling a rectangle, under Bison on the western wall in the Chamber of Symbols, appears to be a diligently shaded trapezoid. Computer deciphering makes it possible to see relic trapezium lines.

Figure 9 The most representative trapezium of the composition Little Horses in the Chamber of Chaos.

A very interesting symbol, created by at least two generations, is the Lattice on the eastern wall in the Dome Chamber (Figure 10). Under the near-vertical crisscrossing red lines one can see an earlier trapezium tinted purple. In the right lower side of Lattice there are three small symbols placed separately, they resemble Cyrillic letters or runes. They look like "T", but the top of the vertical line is a triangle. They might have been created much later in the post-paleolithic time (Figure 10). It is noteworthy that there exists "morphological zoning" of the symbols from the third group on the northern wall in the Chamber of Symbols. On the western side of the wall, there are two double triangles. To the east there are small sketchy zoomorphic images (including Camel 1 and New Mammoth). In the center of the wall, there are complex symbols with blurred contours and radiating elements or trapezia derivatives. On the eastern side, there are three circular symbols with circular arcs. The row of symbols at the end of the eastern wall is crowned with a kind of trident. It is worth mentioning that there is a noticeably greater number and variety of geometric signs in the Kapova Cave than in western caves.4,10 This can be explained by the fact that the cave continued to be the largest local sanctuary for a long time, and images of different traditions and epochs found their reflection in it.

By now, around 200 images have been discovered in the Kapova Cave, zoomorphic images account for about 24%. A large number of abstract geometric symbols (about 40%), that have not been found in other Paleolithic artefacts; including specific trapezia forming a unique system have been found in the Kapova cave. Ochre spots including relic images account for 36%. The work performed enables one to assume the existence of a large number of unknown images coated with calcite sinter crusts. The existence of several groups of images attests to the fact that they were created in different epochs since the late Paleolithic and onwards. Unfavorable environmental conditions in the Kapova cave over thousands of years caused great damage to the drawings, so the images in their initial state, with rare exceptions, are gone. Initially they might have been more contrasting and polychrome. The accumulated material, as well as the discovery of numerous new drawings is convincing evidence that a peculiar center of ancient culture, resembling those in France and Spain (West Europe), although featuring its distinctive identity, existed in the Southern Urals in the Paleolithic.

None.

Author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

©2018 Lyakhnitsky. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.