Journal of

eISSN: 2573-2897

Research Article Volume 2 Issue 2

Laboratoire Archéométrie et Archéologie, France

Correspondence: Thierry Argant, Laboratoire Archéométrie et Archéologie, France, Tel 667934848

Received: June 20, 2017 | Published: November 22, 2017

Citation: Argant T. The impact of Romanisation on Hippophagy and Cynophagy: a long-term perspective from Lyon, France. J His Arch & Anthropol Sci. 2017;2(2):59-69. DOI: 10.15406/jhaas.2017.02.00050

Lyon (Rhône, France) has been permanently occupied since the late Neolithic (c.2000 B.C.) and, up until the end of second Iron Age (mid-1st c. B.C.) at least, the site has regularly produced zoo archaeological evidence for dog and equid consumption. After the establishment of the Roman colony of Lugdunum, however such evidence disappears from faunal assemblages, a time when new phenomena such as dog burial and horse knackery emerges, particularly in suburban areas, only for it to reappear once more during the 2nd c. A.D. This paper traces the changes in human exploitation of horses and dogs during the 1st millennium A.D. and focuses, in particular, on the impact of Roman cultural attitudes towards these species.

Keywords: Romanisation; Hippophagy; Cynophagy; France; Craft working; Iron age; Sheep and goats

Lyon (Rhône, France) has been permanently occupied since the late Neolithic (c.2000 B.C.) and, up until the end of second Iron Age (mid-1st c. B.C.) at least, the site has regularly produced zoo archaeological evidence for dog and equid consumption. After the establishment of the Roman colony of Lugdunum, however such evidence disappears from faunal assemblages, a time when new phenomena such as dog burial and horse knackery emerges, particularly in suburban areas, only for it to reappear once more during the 2nd c. A.D. This paper traces the changes in human exploitation of horses and dogs during the 1st millennium A.D. and focuses, in particular, on the impact of Roman cultural attitudes towards these species.

Historical context

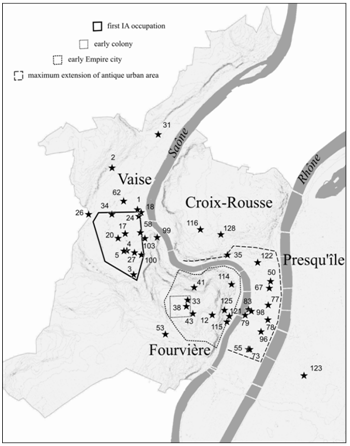

The city of Lyon is located in south-eastern France at the confluence of the River Saône, connecting from the north and the Rhône, flowing from the Alps, which together run south to the Mediterranean (Figure 1). The earliest evidence for settlement has been identified on the alluvial plain of Vaise in the northwest of the city and on the hills surrounding the Rhône in the east (Corbas, Vénissieux and Meyzieu). Since the middle of the 1980s, the development of rescue archaeology has allowed the identification of about thirty sites dating from the Hallstatt D2-D3 and La Tène Al periods and these are distributed over c.150 ha of the plain of Vaise.1 This occupation appears to have been extensive and unenclosed, with denser concentrations of structures found in the southern part of the plain (Figure 2). It is also marked by imported Mediterranean pottery associated with wine consumption. Both structures and finds provide evidence for agriculture and stock-raising alongside specialized craft-working, including iron and copper-alloy working, horn-working and textile production (Table 1).

N° |

Site |

Equids |

Dogs |

Remarks |

Source |

|||||||

Total NISP |

NISP |

Consumption |

Craftwork |

Burial/Knackery |

NISP |

Consumption |

Craftwork |

Burial/Knackery |

||||

Late Neolithic |

||||||||||||

1 |

11-13 rue Roquette |

5 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Argant [18] |

|

2 |

BPNL |

96 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Forest [19] |

|

3 |

Station métro GDL |

14 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Méniel [20] |

|

Early Bronze Age |

||||||||||||

4 |

17-21 rue GDL |

251 |

3 |

? |

? |

- |

2 |

? |

? |

- |

Argant [3] |

|

5 |

29-31 rue GDL |

40 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

? |

? |

- |

Argant [21] |

|

2 |

BPNL |

262 |

4 |

? |

? |

- |

2 |

? |

? |

- |

Forest [19] |

|

3 |

Station métro GDL |

15 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Méniel [20] |

|

Late Bronze Age |

||||||||||||

5 |

29-31 rue GDL |

12 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

? |

? |

- |

Argant [21] |

|

2 |

BPNL |

639 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

22 |

? |

? |

- |

Forest [19] |

|

10 |

Corbas - Grand Champ |

66 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Argant [3] |

|

10 |

Corbas - Grand Champ |

17 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Argant [3] |

|

12 |

Hôpital de l'Antiquaille |

5 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

+ |

- |

- |

radius |

Argant [22] |

13 |

Meyzieu - Les Hernières |

129 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

? |

? |

- |

3 month puppy |

Forest [23] |

3 |

Station métro GDL |

71 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Méniel [20] |

|

15 |

Vénissieux |

100 |

2 |

? |

? |

- |

2 |

? |

? |

- |

Forest [24] |

|

First Iron Age |

||||||||||||

1 |

11-13 rue Roquette |

353 |

1 |

? |

- |

- |

4 |

+ |

- |

- |

clear cutmarks on dog |

Argant [18] |

17 |

14, rue des Tuileries |

731 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

6 |

? |

- |

c |

puppy and old dog |

Argant [25] |

18 |

4-6 rue du Mont d'Or |

500 |

1 |

? |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

not studied yet ! |

unpublished |

2 |

BPNL |

158 |

2 |

+ |

- |

- |

0 |

+ |

- |

- |

Forest [19] |

|

20 |

Horand 1 |

973 |

7 |

+ |

- |

- |

90 |

+ |

+ |

- |

young dogs, skinning |

Argant [7] |

20 |

Horand 2 |

540 |

5 |

+ |

- |

- |

11 |

+ |

- |

- |

Argant [7] |

|

20 |

Horand 3 |

125 |

1 |

+ |

- |

- |

1 |

+ |

- |

- |

Argant [7] |

|

20 |

Horand 4 |

239 |

2 |

+ |

- |

- |

0 |

+ |

- |

- |

Argant [7] |

|

24 |

10, rue Marietton |

522 |

2 |

+ |

- |

- |

3 |

+ |

- |

- |

Argant [7] |

|

25 |

Sérézin du Rhône |

146 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Poulain [26] |

|

26 |

65, rue du Souvenir |

193 |

1 |

+ |

- |

- |

1 |

+ |

- |

- |

Argant [7] |

|

3 |

Station métro GDL |

1083 |

15 |

+ |

- |

- |

8 |

+ |

- |

- |

Méniel [20] |

|

15 |

Vénissieux |

231 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

? |

? |

? |

Forest [24] |

|

27 |

Rue Berthet/Cottin |

692 |

1 |

? |

- |

- |

5 |

? |

+ |

- |

skinning on dog |

Lalaï [27] |

Second Iron Age |

||||||||||||

24 |

10, rue Marietton |

206 |

17 |

? |

? |

? |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

in a ditch |

Argant [7] |

18 |

4-6 rue du Mont d'Or |

500 |

1 |

+ |

- |

- |

1 |

+ |

- |

- |

not studied yet, big dog |

unpublished |

31 |

Chais Beaucairois |

3000 |

3 |

- |

- |

+ |

3 |

+ |

- |

+ |

in tombs : offering food and sacrified individuals |

Argant [10] |

32 |

Clos des Frères Maristes |

6 |

1 |

? |

- |

- |

1 |

? |

- |

- |

Argant [14] |

|

33 |

Hôpital Sainte-Croix |

502 |

2 |

? |

? |

? |

15 |

? |

? |

? |

Krauz [8] |

|

34 |

Îlot Cordier |

687 |

108 |

+ |

- |

- |

6 |

? |

- |

? |

in a ditch |

Jacquet [9] |

35 |

Quartier Saint-Vincent |

478 |

1 |

i |

- |

- |

8 |

+ |

- |

- |

young equids and dogs |

Argant [7] |

26 |

Rue du Souvenir |

1347 |

51 |

? |

? |

? |

4 |

? |

? |

? |

Forest [28] |

|

15 |

Vénissieux |

24 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

+ |

- |

- |

cutmarks on coxal bone |

Forest [24] |

38 |

Verbe Incarné |

2624 |

20 |

? |

? |

? |

1 |

? |

? |

? |

in a ditch |

Goudineau [29] |

Table 1 Location of sites from Late Neolithic to Second Iron Age.

At the end of the second Iron Age, in the middle of the 2nd c. B.C., Vaise remained an important meeting place with large ditches in which waste from feasts has been found discarded and these appear to correspond to a large, enclosed, high-status settlement.2 In 43 B.C., the Senator and Consul, Munatius Plancus, established the Colonia Copia Felix Munatia Lugdunum with the status of Roman Colony of Right (optimo iure) on the summit of the hill of Fourvière. This represented the beginning of an era of prosperity which lasted about two centuries. The city rapidly expanded from the hillside onto the Presqu'île and in 12 B.C., became the provincial capital of the Three Gauls. Thereafter, Christianity gradually became more influential after it was introduced to Lugdunum by large numbers of Greek settlers from Asia Minor. In AD 177, the martyrdom of the Christians of Lyon took place, a point which marked the beginning of a period of decline for the city and by the end of the 3rd c. AD it had lost its status as provincial capital to Treves. The church recovered quickly, however and by the 5th c. A.D. the first cathedral was established in the city whilst the Burgondes occupied the region.

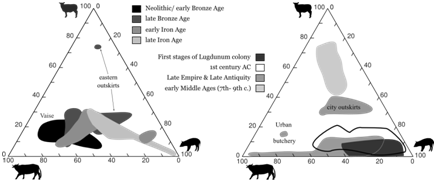

Meat-based diet

To a large extent, cattle (Bos taurus) bones dominate many assemblages from Lyon dating between the late Neolithic and the end of first Iron Age.3 This pattern, particularly during first Iron Age, is quite similar to that recorded for the Saône valley, an area with similar geographical characteristics, while in south-eastern France, with its drier landscape, sheep/goat (Caprinae) remains are more common.4 By the end of second Iron Age in Lyon, pig (Suss domesticus) bones become more common (Figure 3). At the same time, red deer (Cervus elaphus) remains become less frequently identified than brown hare (Lepus europaeus), a change which appears to mirror a decline in the forest in the vicinity, as is shown by pollen analysis.5 At the beginning of the Roman period, pig remains continue to dominate many assemblages, though cattle become increasingly important again over time, a trend which correlates with the establishment of slaughterhouses and butcheries in the Roman town.3 For example, the site of Tramassac Street at the southern gate of the late Roman town revealed a striking example of one of these establishments, producing quantities of processed cattle remains.6 Outside the town limits, sheep/goat bones are more commonly recovered, together with pigs, whilst cattle remains are less frequently identified and later, during the Early Middle Ages, sheep/goats continue to dominate (Table 2) (Table 3).

N° |

Site |

Equids |

Dogs |

Remarks |

Source |

|||||||

Early Empire-Augustean |

||||||||||||

1 |

11-13 rue Roquette |

109 |

3 |

- |

- |

? |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Argant [18] |

|

18 |

4-6 rue du Mont d'Or |

218 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Argant [30] |

|

32 |

Clos des Frères Maristes |

40 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Argant [18] |

|

32 |

Clos des Frères Maristes |

4 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Argant [18] |

|

43 |

Cybèle - D1 |

3587 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

31 |

? |

? |

+ |

Forest [31] |

|

43 |

Cybèle - F2 |

640 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Forest [32] |

|

43 |

Cybèle - F2 |

647 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

? |

- |

? |

gracil tibia's diaphysis : might be fox |

Forest [32] |

43 |

Cybèle - B14 |

3185 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

30 |

? |

+ |

? |

3 individual, healed fracture,cutmark on femur, puppy |

Argant [3] |

46 |

Genas |

71 |

1 |

? |

- |

- |

1 |

? |

- |

- |

beheaded horse, old dog |

Argant [33] |

47 |

Hôpital de Fourvière |

229 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Argant [34] |

|

47 |

Hôpital de Fourvière |

41 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Argant [34] |

|

12 |

Hôpital de l'Antiquaille |

95 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Argant [22] |

|

50 |

Place de la Bourse |

111 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Forest [32] |

|

Early Empire-1st . AD |

||||||||||||

1 |

11-13 rue Roquette |

113 |

5 |

? |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Suspicious marks |

Argant [18] |

1 |

11-13 rue Roquette |

60 |

5 |

? |

- |

+ |

1 |

? |

- |

- |

Equids in well |

Argant [18] |

53 |

19-21 rue Fossés de Trion |

16 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Lalaï [27] |

|

54 |

27 rue Auguste Comte |

45 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Argant [35] |

|

54 |

27 rue Auguste Comte |

308 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Argant [35] |

|

54 |

27 rue Auguste Comte |

107 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

10 |

- |

- |

+ |

Young dog in well |

Argant [35] |

54 |

27 rue Auguste Comte |

52 |

1 |

? |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

3rd phalanx |

Argant [35] |

58 |

4 rue Saint-Didier |

208 |

17 |

- |

- |

+ |

8 |

- |

- |

+ |

Pathology |

Argant [36] |

58 |

4 rue Saint-Didier |

106 |

19 |

- |

- |

+ |

36 |

- |

- |

+ |

Dwarf hound (type 1b) |

Argant [36] |

18 |

4-6 rue du Mont d'Or |

221 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Argant [30] |

|

2 |

BPNL |

589 |

90 |

? |

? |

? |

22 |

? |

? |

? |

Forest [19] |

|

62 |

Clos des Arts |

274 |

53 |

- |

- |

+ |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Funerary context |

Schmitt et al. [37] |

32 |

Clos des Frères Maristes |

167 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Argant [14] |

|

32 |

Clos des Frères Maristes |

29 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Argant [14] |

|

32 |

Clos des Frères Maristes |

57 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Argant [14] |

|

43 |

Cybèle - D1 |

2137 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

+ |

Medora |

Forest [31] |

67 |

Grand Bazar |

300 |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Mandible in pit |

Lalaï [27] |

47 |

Hôpital de Fourvière |

354 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Argant [34] |

|

47 |

Hôpital de Fourvière |

83 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Argant [34] |

|

47 |

Hôpital de Fourvière |

424 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Argant [34] |

|

47 |

Hôpital de Fourvière |

658 |

1 |

? |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

1 limb |

Argant [34] |

12 |

Hôpital de l'Antiquaille |

294 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Argant [22] |

|

73 |

Hôtel de Cuzieu |

95 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Argant [25] |

|

73 |

Hôtel de Cuzieu |

163 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

5 |

? |

- |

- |

Young and adult gracil dogs |

Argant [25] |

75 |

La Boisse |

106 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

+ |

Canid in incineration |

Silvino [38] |

50 |

Place de la Bourse |

42 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Arlaud [39] |

|

77 |

Place de la République |

79 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Arlaud [39] |

|

78 |

Rue Bellecordière |

155 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Argant [3] |

|

79 |

rue Colonel Chambonnet |

209 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Argant [3] |

|

79 |

rue Colonel Chambonnet |

135 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Argant [3] |

|

79 |

rue Colonel Chambonnet |

50 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Argant [3] |

|

79 |

rue Colonel Chambonnet |

439 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

? |

? |

? |

Argant [3] |

|

83 |

Théâtre des Célestins |

179 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

4 |

? |

? |

? |

Argant [5] |

|

83 |

Théâtre des Célestins |

334 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

? |

? |

? |

Argant [5] |

|

15 |

Vénissieux |

143 |

1 |

? |

- |

? |

4 |

? |

- |

? |

3 dogs |

Forest [24] |

Table 2 Location of sites in Early empire-augustean.

N° |

Site |

Equids |

Dogs |

Remarks |

Source |

|||||||

Early empire - 2nd c. |

||||||||||||

1 |

11-13 rue Roquette |

18 |

2 |

? |

- |

? |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Argant [18] |

|

1 |

11-13 rue Roquette |

44 |

6 |

+ |

- |

+ |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Cutmarks on humerus |

Argant [18] |

17 |

14, rue des Tuileries |

774 |

11 |

+ |

+ |

- |

14 |

- |

- |

? |

Sawed bones |

Argant [40] |

2 |

BPNL |

544 |

133 |

? |

? |

+ |

33 |

? |

? |

? |

Forest [19] |

|

27 |

Rue Berthet/Cottin |

47 |

4 |

? |

? |

? |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

Lalaï [13] |

|

32 |

Clos des Frères Maristes |

1008 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

3 |

- |

- |

+ |

Argant [14] |

|

32 |

Clos des Frères Maristes |

117 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Argant [14] |

|

46 |

Genas |

2 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

+ |

Dwarf hound (type 1b) |

Argant [33] |

47 |

Hôpital de Fourvière |

194 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

? |

- |

? |

Argant [34] |

|

12 |

Hôpital de l'Antiquaille |

1938 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Feast's wastes |

Argant [22] |

73 |

Hôtel de Cuzieu |

45 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Argant [25] |

|

96 |

Place Antonin Poncet |

1 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

+ |

Dog's grave in little channel |

unpublished |

50 |

Place de la Bourse |

91 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

4 |

? |

? |

? |

Arlaud [39] |

|

98 |

Place des Célestins |

102 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Arlaud [39] |

|

99 |

Quai Arloing |

730 |

3 |

- |

+ |

+ |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Horse's patella in a child grave |

Delaval [11] |

100 |

Quartier Saint-Pierre |

1 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

+ |

Dog's grave with its bowl |

Delaval [11] |

100 |

Quartier Saint-Pierre |

1 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

+ |

- |

Dismembered dog, thrown on the road side |

Delaval [11] |

100 |

Quartier Saint-Pierre |

5 |

5 |

- |

- |

+ |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Mass grave |

Delaval [11] |

103 |

rue du Chapeau Rouge |

1 |

1 |

- |

- |

+ |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Foal in the filling of a room of a ceramic workshop. |

unpublished |

83 |

Théâtre des Célestins |

263 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

? |

? |

? |

Argant [5] |

|

83 |

Théâtre des Célestins |

21 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

? |

? |

? |

Argant [5] |

|

83 |

Théâtre des Célestins |

23 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Argant [5] |

|

46 |

Genas |

2 |

1 |

- |

- |

+ |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Foal ABG associated with calf |

Argant [33] |

83 |

Théâtre des Célestins |

110 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Argant [5] |

|

53 |

19-21 rue Fossés de Trion |

8 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Rémy [27] |

|

Late Empire |

||||||||||||

54 |

27 rue Auguste Comte |

199 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

+ |

Young dog in well |

Argant [35] |

54 |

27 rue Auguste Comte |

376 |

2 |

- |

- |

+ |

2 |

? |

- |

? |

Equids and dogs in well. Pathological and gnawed dog |

Argant [35] |

47 |

Hôpital de Fourvière |

658 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

4 |

- |

- |

? |

Small dog |

Argant [34] |

73 |

Hôtel de Cuzieu |

37 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

Argant [25] |

|

114 |

Hôtel de Gadagne |

79 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

? |

? |

+ |

Argant [3] |

|

115 |

Parking Saint-Georges |

1151 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

? |

? |

? |

Ayala [41] |

|

98 |

Place des Célestins |

457 |

6 |

? |

? |

? |

2 |

? |

? |

? |

Arlaud [39] |

|

78 |

Rue Bellecordière |

100 |

3 |

? |

? |

? |

2 |

? |

? |

? |

Argant [3] |

|

83 |

Théâtre des Célestins |

324 |

1 |

? |

? |

? |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Argant [5] |

|

116 |

7-11 rue des Chartreux |

66 |

36 |

- |

+ |

+ |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Sawed horses bones, exposition |

Argant et al. [42] |

Late antiquity |

||||||||||||

58 |

4 rue Saint-Didier |

57 |

19 |

? |

- |

+ |

1 |

+ |

- |

- |

Cutmarks on equid vertebra ?, elbow dislocation on dog |

Argant [36] |

114 |

hôtel de Gadagne |

865 |

2 |

? |

? |

? |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Argant [3] |

|

115 |

Parking Saint-Georges |

574 |

11 |

+ |

- |

? |

4 |

? |

? |

? |

Donkey and horse |

Ayala [41] |

122 |

Place des Terreaux |

412 |

3 |

? |

? |

? |

5 |

? |

? |

? |

Arlaud [39] |

|

123 |

rue du Père Chevrier |

94 |

4 |

? |

? |

? |

5 |

? |

? |

? |

Blaizot et al. [43] |

|

124 |

rue Mgr Lavarenne |

764 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Argant [44] |

|

125 |

Tramassac |

8815 |

20 |

+ |

? |

- |

43 |

? |

? |

? |

Arbogast [6] |

|

15 |

Vénissieux |

66 |

2 |

? |

? |

? |

4 |

? |

? |

? |

Forest [24] |

|

Early Middle Age |

||||||||||||

58 |

4 rue Saint-Didier |

69 |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

46 |

- |

- |

+ |

Erratic distribution of equids, dog ABG |

Argant [36] |

128 |

41-43 rue des Chartreux |

663 |

1 |

? |

? |

? |

2 |

? |

? |

? |

Ayala et al. [45] |

|

129 |

Décines- Montout |

120 |

23 |

+ |

- |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

Ferber [46] |

|

114 |

Hôtel de Gadagne |

246 |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

? |

? |

? |

Argant [3] |

|

98 |

Place des Célestins |

2029 |

9 |

? |

? |

? |

2 |

? |

? |

? |

Arlaud [39] |

|

Table 3 Location of sites from Early empire - 2nd c. to Early middle age.

History of the horse (Equidae)

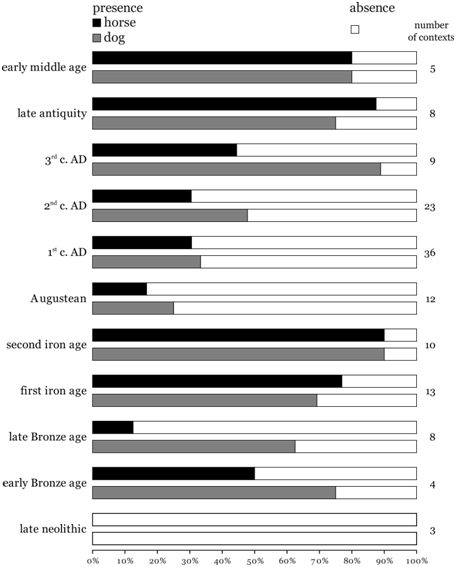

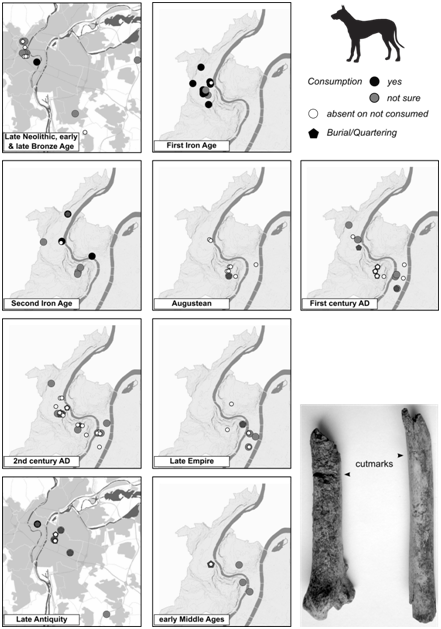

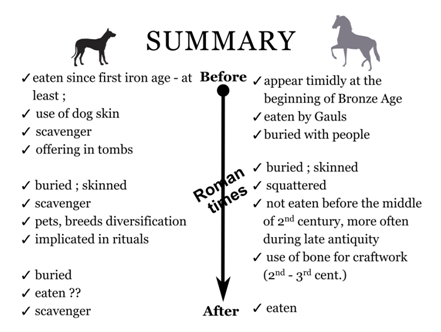

Horse remains occur in zooarchaeological assemblages continuously from the early Bronze Age to the second Iron Age (Figure 4). During the Roman period, for about a century and notably in the town centre, their bones are only recovered from a very limited number of contexts, but gradually become more frequent again from the 2nd c. A.D.

During the first Iron Age, evidence for butchery on equid bones is rare, though a thoracic vertebra from rue du docteur Horand displays clear cut marks.7 In addition, pathologies are also witnessed on some horse bones in this period, indicating their difficult living conditions at that time (Figure 5). In the second Iron Age, horse consumption is more evident, though evidence that horses were also exploited in other ways is also detectable. On some sites, such as rue Roquette in Vaise, cut marks have been observed on meat-baring parts of the skeleton, as well as patterns of bone breakage similar to that seen on cattle in particular. On the top of the hill of Fourvière, many complete horse bones were discovered in a ditch at Verbe Incarné in association with a high number of pig bones, remains which were interpreted as the debris from a large feast,8 though here it is uncertain whether horse flesh was consumed. A similar pattern was also recorded at îlot Cordier, though this time horse bones were predominantly found in association with cattle remains and were butchered in a similar manner, suggesting that horse consumption had taken place.9

In the necropolis of Chais Beaucairois, four tombs contained the bones of both humans and domestic mammals. Among them, elderly stallions (more than 10 years old) were found lying on their side in the funeral chamber.10 These aged animals showed pathologies associated with the carrying of heavy loads and we can suppose that these were used as mounts, perhaps belonging to the deceased. Alternatively, they may have been chosen from animals unfit for service, as a symbolic gesture, in a context where they were of great value.

In the initial period of the Roman colony, horse bones are lacking from most sites, especially in the centre of the city (Figure 6). At the same time, however, the first evidence for knackery is also identified from the remains of complete long bones plus some associated bone groups discovered, notably in ditches located around the necropolis, outside of the compendium in the Vaise suburbs. During the 2nd c. A.D., evidence for horse consumption returns, once again in the form of fractured bones which display cut marks from meat-baring parts of the skeleton. However, this evidence is still restricted to suburban areas, whereas horse bones remain completely absent from within the colony. Occurrences of horse butchery in funerary areas is also fairly common from this phase, along with more rarely horses buried in pits, such as at boulevard périphérique nord de Lyon. At the quartier Saint-Pierre, an exceptional burial of humans and horses were found together in a pit along a suburban street.11

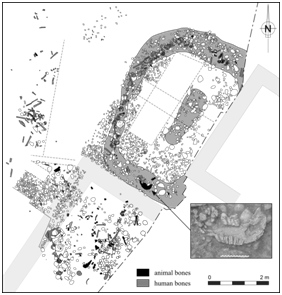

The occurrence of equid bones amongst craft-working waste became more common during the 3rd c. A.D., whilst in the early Roman period only cattle bones were used for this purpose. This may indirectly indicate evidence for horse consumption if the retrieval of long bones for craft-workers was integrated with the butchering process. On the site of rue des Chartreux, bone-working waste was found deposited in a rectangular ditch which surrounded an empty ‘inhumation’ pit. Within the ditch, disarticulated human skulls and long bones were identified along with a very poorly preserved horse skull, a lion tibia and a bear molar (Figure 7). The interpretation of the feature, possibly a structure, is difficult to determine. It may have been a monument erected to commemorate an event, perhaps associated with the amphitheatre, which may explain the association of people and wild animals in this context, or perhaps a trophy erected following one of the battles of 197 between the armies of the rival emperors Albinus and Septimus Severus which took place around Lyon.12

By the end of Roman period, horse bones continued to be recovered in very small amount from the slaughterhouses and urban butcheries at Tramassac, perhaps indicating that the consumption of horse meat also continued, though direct evidence is lacking.6 Similarly, in the Early Middle Ages, the consumption of horse meat is suspected from remains on some sites, whilst only a few centuries later, it became very common in the countryside around Lyon, especially on agriculturally-poor land on the Dombes plateau to the north-east.

History of the dog (Canis familiaris)

Canid bones have been recovered from the majority of sites in Lyon dating from the early Bronze Age and, similar to horses, the Roman period appears to be an exception in that continuum (Figure 4). It is difficult to identify evidence for dog consumption from Bronze Age sites, notwithstanding the possibility that some bones from that period might have derived from wolves. Contrastingly, cynophagy is frequently mentioned dating to the first Iron Age. At Rue Roquette, for example, scapula and os coxae bones exhibited clear evidence for cut marks, suggesting that dog meat had been consumed. On other sites, as at rue du Docteur Horand and rue Berthet, butchered phalanx and metapodials suggest the exploitation of skins, whilst the first evidence for the inhumation of a dog is also testified at rue Berthet.13

During the second Iron Age, evidence for dog consumption continues. For example, at Saint-Vincent, clear and deep cut marks appear on dog tibiae. Other specimens were associated with inhumation burials of the Chais beaucairois14 (Figure 8). At this site, two matching mandibles from a puppy were placed on top of a funerary vessel, possibly as a food offering. Notably, a similar deposit was identified at the necropolis of Lamadelaine in Luxembourg, where Méniel noted the presence of puppy and chicken bones placed on top of a pot as possible food items.15

During the early Roman period, evidence for canids scavenging on carcass parts is regularly observed from gnaw marks on bones, suggesting that dogs were common on the streets and around rubbish dumps. However, evidence for dog consumption disappears during this period (Figure 8), whilst dog burials become more prolific within the city. A more exceptional find includes the identification of dog bones amongst burned offerings in a funeral pyre at the villa of La Boisse. There is also evidence for small dog breeds in the Roman town, for example at Verbe Incarné, whilst evidence for dwarf hounds have been found close to the town at Rue Saint-Didier and at nearby rural settlements such as Genas. Similarly, in the 2nd c. A.D., no evidence for the consumption of dog meat has been identified, though dog burials continue to be common. However, some remains demonstrate that individual dogs may have been treated quite differently by people in the town. One dog, with poorly-healed fractures, had been skinned before being disposed of along a street in the quartier Saint-Pierre.11 In contrast, on the same site, another individual was carefully buried with a vessel, which may have been the dog’s bowl. On this specimen, the right humerus demonstrated a healed fracture, though this appeared to have mended well, perhaps with the help of a thoughtful master.[1]

During Late Antiquity (mid-4th c. A.D.), in the suburban Vaise area, at rue Saint-Didier, an adult ulna shows cut marks on the proximal end, perhaps indicating that the dog had been consumed. At Hôtel de Gadagne, a dog was found partially burned and deposited with coins in the foundations of a hypocaust, just prior to being sealed by a concrete slab.16 By the Early Middle Ages, some instances of dog burial continue, whilst isolated bones may be more ephemeral evidence for dog consumption, though this remains to be proven.

[1]Ibid 65.

To conclude, evidence that dogs and horses were eaten before the establishment of the Roman colony at Lyon is found at a number of sites. However, a Roman taboo17 over the consumption of dogs and horses appears to have been exercised from the beginning of that period (Figure 9). At the same time, a diversification of dog breeds occurred when they also began to appear in a range of ritual practices and some may have been cared for. Contrastingly, evidence for stray dogs scavenging in the town streets also becomes more common, with a number exhibiting pathologies suggesting that they had been poorly treated.

For horses and other equids, a different history is evident. Horses were eaten by the Gauls, but also buried alongside people and other domestic species. If their consumption stopped strictly with the arrival of the Romans, it appears to have started once more from the middle of the 2nd c. A.D. At this time, horse bones were also exploited for craft-working and raw resources may have been supplied through knackers. And, since they were not eaten, their carcasses appear to have been scattered in the suburbs and in the neighbourhood of the necropolis.47,48

I am grateful to Martyn Allen who helped me with the composition of this article, after I was unable to attend the 2014 Roman Archaeology Conference session on which it is based, and also to Rowan Lacey (Éveha) for his helpful review of my English.

Author declares there is no conflict of interest.

©2017 Argant. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.