Journal of

eISSN: 2573-2897

Research Article Volume 1 Issue 2

University of Strasbourg, France

Correspondence: Jacques Connan, University of Strasbourg, France

Received: April 04, 2017 | Published: April 19, 2017

Citation: Connan J, Zumberge J, Imbus K. Identification of two bitumen pieces from the neolithic (vth millennium BC) at Al-Buhais 18 (Sharjah). J His Arch & Anthropol Sci. 2017;1(2):33-36. DOI: 10.15406/jhaas.2017.01.00010

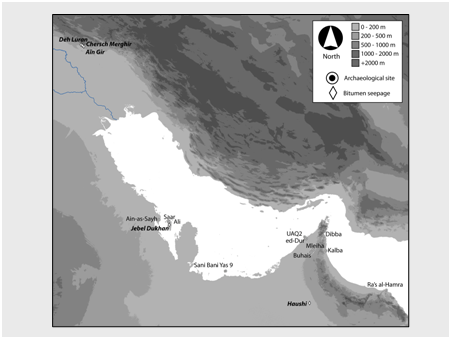

Two bitumen-like pieces (2-4cm) were found by excavators during the 2nd season of excavations at al-Buhais 18, a Neolithic burial ground and dwelling located in the desert in the central Region of the Emirate of Sharjah. Radiocarbon dates place the site into the fifth millennium BC. No bitumen beads as those unearthed in-situ around the neck of a human at UAQ 2 (end of fifth millennium BC, Figure 1) or bitumen traces on lithics or on other objects, were noticed among the excavated material. The two masses are single finds which confirm the scarcity of bitumen occurrences during this early period of the Gulf history. Bitumen remains are seldom identified in the excavations of these early periods in the Gulf.1,2 Consequently, the discovery of these isolated two pieces of bitumen at al-Buhais 18 raises two main questions:

Keywords: Bitumen, Fragments, Asphaltenes, Graveyard, Chromatography

Among the numerous fragments of charcoal under study at al-Buhais 18,3 selected two small pieces Table 1 which were expected to be bitumen. Hans-Peter Uerpmann gave the following comments about the samples:

Sample number |

Location |

Reference |

Comment |

Date |

Binocular exam |

1947 |

al-Buhais 18 |

22235 |

Bitumen? Single find |

Neolithic |

Single lump of pure black bitumen with aconchoidal fracture |

1948 |

al-Buhais 18 |

20052 |

Sediment |

Neolithic |

Lumps of pure bitumen with conchoidal fracture with incrusted stone and sand from excavation |

Table 1 Basic information on the analysed bitumens from al-Buhais 18

“Unfortunately there is little information on the two finds. For one of the pieces there is no information except that it is from the Neolithic graveyard and from a depth at least 30 cm below the modern surface. Therefore the context should be securely 5th millennium BC. The other piece is from the context of the burials DG and DH without closer specification. Unfortunately DH is disturbed, although not certainly after 4200 BC. DG was also disturbed by the same event, but seems to have been a primary burial whereas DH is a secondary burial containing the remains of at least 4 individuals. In any case there is no reason to believe that the bitumen finds are post-Neolithic, because we have no later admixtures in the graveyard”. As a key feature, the bitumen pieces are unique discoveries at al-Buhais 18. No other bitumen occurrences have been recorded.

Analytical methods are those which have been published elsewhere.4 The CH2Cl2 extract was desasphalted using hexane. The desasphalted fraction was separated into saturated hydrocarbons, aromatic hydrocarbons and resins by gravity flow column chromatography using a 100-200 mesh silica gel support activated at 400°C prior to use. Gross composition data are listed in Table 2 with carbon isotope values on bulk bitumen and chromatographic fractions.

Sample number in data bank |

Lab number |

Location |

Organic extract (W% / sample) |

Sat (% ) |

Aro. (%) |

Res.(%) |

Asp. (%) |

d13cech.brut |

d13csat. |

d13caro. |

d13casp. |

1947 |

JCUE1947 |

al-Buhais 18 |

90.5 |

8.3 |

38.8 |

27.3 |

25.6 |

-26.4 |

-26.7 |

-26.4 |

-26.9 |

1948 |

JCUE1948 |

al-Buhais 18 |

64.5 |

8.1 |

39.9 |

27.3 |

24.7 |

-25.2 |

-26.7 |

-26.4 |

-26.9 |

Table 2 Gross composition of the extractable organic matter and carbon isotopic data on bulk and chromatographic fractions

Dichloromethane yields confirm that both samples are pure bitumen, with sample n°1948 contaminated by sand and gravels from the excavation (Figure 4). Both appear not to have been processed and mixed with fillers to prepare bituminous mastic. The geological character of the samples, well preserved, clearly appears in the gross composition which shows a very high amount of aromatic hydrocarbons (39-40%) and a moderate amount of asphaltenes (around 25%). These bitumens are significantly different from archaeological ones in which asphaltenes strongly predominate (>75 %) and aromatics are generally drastically reduced (between 0 and 5 %) by oxidation.5 One should notice that the gross composition of the two samples is almost identical; consequently, both bitumens are likely from the same source.

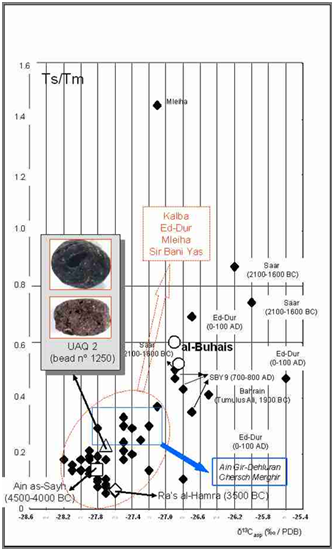

Carbon isotopic data on bulk bitumen and associated fractions are given in Table 2. Bulk isotopic values (-26.4 and -25.2‰/PDB) suggest that the bitumen may originate from Iran. Differences between bulk values may be due to occurrence of carbonates in samplesn° 1948. As noted later, molecular chemistry did not show any 18a(H)-oleanane in the samples. This diagnostic molecule of Iranian oil seeps from Khuzistan and Fars occurs in oils having similar bulk carbon isotopic values. Isotopic values, measured on fractions and especially on asphaltenes (-26.9‰/PDB) rules out the Haushi tar seep (Figure 1) in Oman (-34.4‰ / PDB,2 as the potential source. Isotopic values of asphaltenes (-26.9‰/PDB) falls close to the average value (-26.7‰ / PDB) of asphaltenes from 10 crude oils and tars from the Awali oil field in Bahrain. However the molecular chemistry, especially Ts/Tm, reveals that the Bahraini oils and tars are more mature than the al-Buhais bitumen (Ts/Tm between 0.77−1.33 instead of 0.52-0.60 at al-Buhais). Therefore the oil seeps of Bahrain which are located at Jebel Dukhan (Figure 1) in the central part of the island, seem not to be the source of the al-Buhais bitumen.

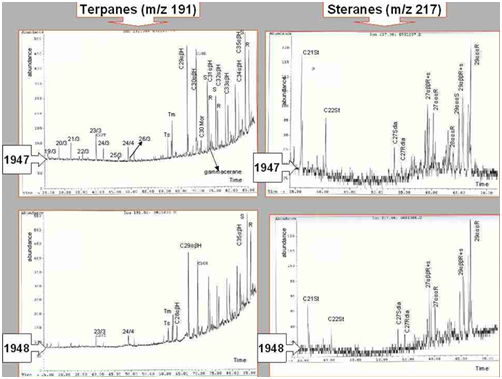

Investigations were completed using molecular chemistry on saturated and aromatic hydrocarbons analysed by GC-MS. Both bitumen’s are biodegraded oils with reduced n-alkanes in samplen° 1947 and no n-alkanes in samplen° 1948. Aromatic hydrocarbons did not provide any exploitable signals especially for biomarkers like steroids, secohopanoids and benzohopanoids. Saturated hydrocarbons contain significant amount of steranes and terpanes which fingerprints are reproduced in Figure 2. These fingerprints, very much alike, confirm that both bitumens originated from the same source. Terpanes are without 18a(H)-oleanane as was expected on the basis of the carbon isotope values, measured on bulk samples. Steranes are dominated by regular steranes in which C28 compounds are very low. Steranes show a fairly immature pattern and isomerisation, as seen in C27 and C29 compounds is not completed (C29aaaS/C29aaaR = 0.5).

In order to investigate the question of the source of the al-Buhais bitumens, a comparison of their chemical data was achieved using diagnostic parameters from other sites in the Gulf (Figure 1)). As was underlined previously, carbon isotope data suggests an Iranian origin for Bahrain oil seep has already been discarded. A plot of Ts/Tm vs. d13C of asphaltenes (Figure 3) shows several features:

Sample number |

Location |

Ts/Tm |

Ga/C3 1HR |

Rearr/Reg |

Ster/Terp |

%C27 |

%C28 |

%C29 |

1947 |

al-Buhais 18 |

0.6 |

0.18 |

0.55 |

0.12 |

34 |

23.7 |

42.3 |

1948 |

al-Buhais 18 |

0.52 |

0.16 |

0.5 |

0.1 |

31 |

23.9 |

45.1 |

Table 3 Some biomarker ratios on steranes and terpanes

Ts=18α-22,29,30-Trisnorneohopane, Tm=17α-22,29,30-Trisnorhopane, GA=Gammacerane, C31HR=17 α,21 β -22R-C31Hopane, Rear/Reg = Rearranged Steranes/Regular Steranes, Ster/Terp = Steranes/Terpanes, %C27 = %5 α,14,17β-20S+20R-Cholestane, %C28=%5 α,14β,17 β -20S+20R-Methylcholestane, %C29=%5 α,14 β,17 β -20S+20R-Ethylcholestane.

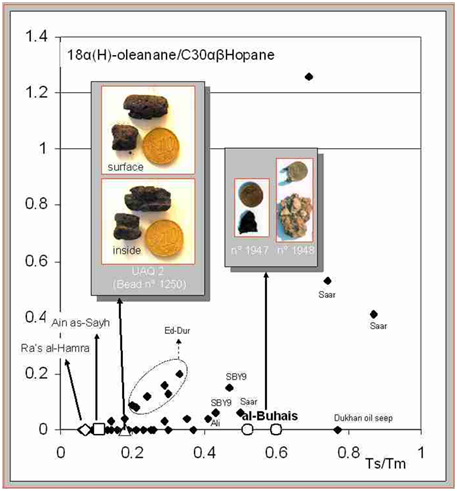

To investigate a possible genetic relationship of al-Buhais bitumens with some bitumens from other sites in Bahrain and the Emirates, a plot of Ts/Tm vs. 18a(H)-oleanane has been examined. Figure 4 gathers the results and shows that the bitumens from Saar, Ali and Sir Bani Yas, which were possibly correlated to the bitumens of al-Buhais, contain 18a(H)-oleanane and therefore do not belong to the same genetic family as al-Buhais bitumen. These bitumens undoubtedly originate from the Khuzistan and Fars provinces in Iran. The oil seep from a geode collected at Jebel Dukhan in Bahrain Island also does not match since its Ts/Tm is too high and indicates a higher degree of maturity.

As a consequence of the combined integration of isotopic and molecular data, it must be concluded that the origin of the two pieces of bitumen, discovered at al-Buhais remains unknown. Carbon isotopic data favours an Iranian origin but the absence of 18a(H)-oleanane has not validated this hypothesis. The bitumen masses may have a local carbonate source as a minute solid bitumen show in fractures. This source should be older than Cretaceous as suggested by the low C28/C29 sterane ratios. The Jebel Faya anticline is built up of metamorphic rocks overlain with Upper Cretaceous marine limestone.9 Therefore this carbonate hill in the vicinity of al-Buhais, does not appear as the likely source of bitumen pieces.

There is no indication to what utilisation these bitumen masses were devoted. These bitumen pieces are single discoveries in a cemetery context and were found among charcoals. Was bitumen used for ignition of fire? Perhaps but the bitumen remains are scarce and only limited to two pieces. The bitumen, at a pure state, is a pristine geological sample which has not been processed as in the UAQ2 cemetery where bitumen is mixed with other fillers to prepare a bituminous mastic in which the beads, found in-situ around the neck of one individual, was shaped. At present, the bitumens of al-Buhais 18 keep their secret and remain an enigma by several key aspects: for what purpose was the bitumen used was brought and from where was it imported?

None.

Authors declare there is no conflict of interest in publishing the article.

©2017 Connan, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.