Journal of

eISSN: 2377-4312

Case Report Volume 3 Issue 4

1Chungnam National University, Korea

2Laboratory of Veterinary Internal Medicine, Seoul National University, Korea

3Gangwon National University, Korea

4Honbuk National University, Korea

5Kyungpook National University, Korea

6Chonnam National University, Korea

Correspondence: Bae-Keun Park, College of Veterinary Medicine, Chungnam National University, Daejeon, Korea, Tel 823 3250 8677, Tel 824 2821 5849

Received: May 02, 2016 | Published: June 22, 2016

Citation: Park SJ, Ha NR, Ryu SY, et al. Subcutaneous canthariasis due to Tenebrio molitor larva (coleoptera: tenebrionidae) in Egretta intermedia. J Dairy Vet Anim Res. 2016;3(4):134-137. DOI: 10.15406/jdvar.2016.03.00086

Canthariasis is a phenomenon where act as parasites and infect humans and other animals temporary by ingesting the beetle larvae. This report highlights the rare subcutaneous canthariasis finding in an avian species, Egretta intermedia, due to a yellow mealworm. On August 2013, a bird was transferred to the Chungnam National University wild animal rescue center, Republic of Korea from the wild envelopment where it died and was anatomized. A single larva was detected in the space between the esophagus and trachea of bird after skinning. The larva was identified to be a yellow mealworm, Tenebrio molitor.

Keywords: subcutaneous canthariasis, yellow mealworm, tenebrio molitor l, egretta intermedia

The invasion of body tissues by beetle larva is called canthariasis, whereas invasions such tissues by adult beetles is called scarabiasis. Canthariasis by coleopteran larvae is a rare and poorly known entity. Coleoptera constitutes the largest insect order and beetles are second to Diptera in importance as invaders of the human body as well as other animals. This disease is distinguished from myiasis and scholeccisais. The terms myiasis is the invasion of living body tissue or cavities by the larva of flies. Canthariasis and scholechiasis both show similar symptoms and conditions produced by beetle larvae and moth larvae respectively. Both have a few case histories that have been reported in the literature. Also, scarabiasis is a condition where beetles temporarily infest the alimentary canal and refers to the passing of live beetles in feces.1‒4 Tenebrionids is widely represented in the fauna in steppes and deserts. The family Tenebrionidae is one of the largest in the animal kingdom, comprising approximately 15,000 described species.5 They are especially abundant in many regions of the world. Mealworms are omnivorous and can eat all kinds of plant materials as well as animal products such as meat and feathers.6

The Tenebrio species (mealworms) normally overwinters in the larval stage and pupation occurs in spring and early summer at which time adults begin to appear. Tenebrio molitor L. (yellow mealworm), commonly referred to as mealworms, is a cosmopolitan secondary pest and scavenger of many stored cereal products. T. Molitor are also found in chicken and other bird houses where feathers, food, and excrement are mixed.7 The yellow mealworms have become synathropous and occur in houses and household structures. T. Molitor L. firstly eat the germs of stored grains and can feed on a wide variety of plant products such as flour, tobacco, ground grains, and foodstuffs.6,8 Also, the larvae of T. Molitor are widely available as pet food for birds, fish, and reptiles.9 The mammalian parasitism of T. Molitor L. is uncommon in the literature and the worm is not obligate parasite of animals. Canthariasis by mealworms is rarely found in man and poorly known entity in man and animal.3,10 We report a case of subcutaneous canthariasis due to T. Molitor L., in a wild bird Egretta intermedia.

On August 2013, an intermediate egret (B.W. 150g), E. intermedia, was transferred from the wild envelopment to the Chungnam National University wild animal rescue center, Korea, died and was anatomized. An insect larva was detected in the space between the esophagus and trachea after skinning (Figure 1A). The larva was yellow in color, shading to a yellowish brown toward each end, dark brown jaw, long and cylindrical in shape, and 27 mm in size (Figure 1B). The body was hardened and segmentation of the abdomen is clearly visible. The head was visible in dorsal view without setae.

For scanning electron microscopy, the larva washed five times with 0.2 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.3), fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde and post fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide at 4°C. The specimen was dehydrated in a graded ethyl alcohol series, dried by CO2 critical point, coated with gold and examined by SEM (S-4800, Hitachi) at 15 kV.

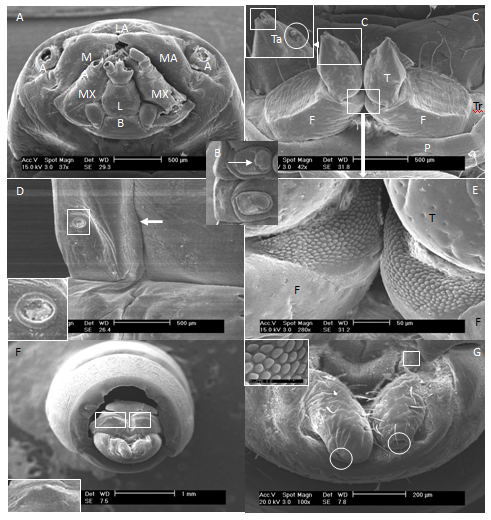

The head capsule was 2.56 mm wide and includes basement of paired antennae, mandibles, maxillae, labium and labrum (Figure 2A). The mouth part was chewing type. Antennal and mandibular bases were not widely separated. Mandible had not tubercle dorso-laterally. But, the labium had tubercle laterally. Three pairs of short legs behind the head were visible from the ventral view and all similar in size (Figure 2B). The legs had some color as body; glabrous prococoxae; femur with some of fine setae; tibia with a sensory papilla; tarsungulus (Figures 1B, 2B & 2C).

The apex of the tarsungulus was considerably more strongly sclerotised than the base, and the distinct division was characteristic (Figure 2C). Abdominal prolegs were absent. Abdominal spiracles were ovate, presented on segments 1-6 without setae. Spiracularperitreme were oval without crenulations (Figure 2D). The sternopleural sutures presented on abdominal segments 1-8 (Figures 1B & 2D). The larva has no hairs at the sides of body segments, but do have a pointed tail segment that is typically forked or notched in the center. Tergite 9 had a pair of sclerotized, prominent, bifurcated dorsal spines on the front of horizontally projecting urogomphi which have some setae on the dorsal, inner surface and basement, and have pore its each latero-teminals (Figures 2F & 2G). Also, the dorsal surface of tergite 9 had not the excavation. Urogomphi are irregularly rounded at apex and with little setae, pore at the latero-terminal, tubercle on inner surface near base (Figures 2F & 2G).

We identified the larvae by the key of identification by Watt;5

Key to the larvae of Tenebrioninae by watt

The mealworm beetle forages on plant products and causes damage to their total mass and nutritive value.11 Also, the T. Molitor L. are used as pet and human food in some parts of the world.8,12 Because they are high in protein and fat and consume large amount of fiber, they represent a good food source. Now a day, it is studied as a potential human novel-food.13 The worm not only eats stored food, but also contaminates it with exuviates excrements and dead insects. T. Molitor L. is omnivorous and originates generally from damp, dark places where cereals may be decaying.

The mealworm has a hard, shiny cuticle that gives a striking resemblance to the wireworm of family Elateridae. Wireworms are the soil-dwelling larvae of click beetles. They resemble mealworms and are slender, elongate, yellowish to brown with smooth, tough skin. There are six short legs close together near the head, and the tip of the abdomen bears a flattened plate with a pair of short hooks. But, wireworms can be differentiated from mealworms by the mouthparts. In Elateridae, the larval mouthparts face forward. The body is usually cylindrical, but flat on the lower side.6,8

Mealworms are the larvae of two species of darkling beetles in the family Tenebrionidae, the yellow mealworm beetle (Tenebrio molitor Linnaeus, 1758) and the smaller and less common dark or mini mealworm beetle (Tenebrio Obscurus Fabricius, 1792). Mealworm beetles are indigenous to Europe and are now distributed worldwide.6 T. Molitor L. are yellow in color, shading to a yellowish brown toward each end and at the articulation of each joint. The mature larva is of a light yellow-brown color, 20 to 32 mm long, and weighs 130 to 160mg.6 In our study, the larva was 27 mm in size. The tail terminates have two short spines. T. Obscurus L. also resembles very closely that of the yellow meal worm. It is of the same size and shape, but differs in color, including much darker brownish markings. Adult T. Molitor lays ovoid, elongated eggs, covered with some sticky substance with which it attaches eggs to the substrate. Small, whitish larvae hatch from the mealworm’s eggs. After a few days, they turn yellowish and produce a hard, chitinous exoskeleton. An adult larva weighs about 0.2g and is 25-35mm long. The larvae are very voracious and highly resistant to low temperature; they can remain alive for 80days at -50˚C. The pupa is a free-living creature, 12-18mm long and of creamy white color.1

The larvae of Tenebrio and other Tenebrionini have the front legs longer and stouter, and the apex of the tarsungulus considerably more strongly sclerotised than the base, although the distinct division characteristic of Blapimorpha is lacking. In our study, the apex of the tarsungulus divided into two. In larvae, as in adults, there is a series of forms intermediate between the most specialized Blapimorpha and Tenebrio, so that it is not desirable to split Blapimorpha off as a separate subfamily.5 The "Opatrinae" of Koch14 and others were Blapimorpha with a deeply emarginate clypeus in the adult. Therefore, they may be a monophyletic group, but are not worthy of subfamily status.

Beetle larvae have been recovered from human organs; tonsils,10 nose and urinary bladder,15 umbilical cord,16 and the gastro-intestine tract.3,10,17 However, the alimentary canal is the most common habitat for parasitizing beetle larvae.10 Therefore, the gastrointestinal canthariasis is usually found in humans.3 On the other hand, the cases of extra alimentary canal canthariasis are especially rare in animals same as our case. In cases of gastro-intestinal canthariasis by beetle larvae, mealworms are the ones most often implicated. Most of the time, eggs or larvae are ingested in cereals and various breakfast foods, and in either case, live larvae can eventually be passed and excreted through the feces.3 In our case, a larva of insect was detected in the space between the esophagus and trachea under the skin of neck of a wild bird, E. Intermedia. In our study, the worm was identified to be a T. Molitor L. This report is a rare case of subcutaneous canthariasis due to a yellow mealworm, T. Molitor L, in a wild bird.

This work was supported by research fund of Chungnam National University.

Author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

©2016 Park, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.