Journal of

eISSN: 2377-4312

Research Article Volume 13 Issue 1

1Escuela profesional de Zootecnia, Universidad Nacional de San Antonio Abad del Cusco, Peru

2Centro experimental La Raya, Universidad Nacional de San Antonio Abad del Cusco, Peru

3Escuela profesional de Medicina Veterinaria, Universidad Nacional de San Antonio Abad del Cusco, Peru

Correspondence: P Walter Bravo, Escuela de Medicina Veterinaria, Universidad Nacional de San Antonio Abad del Cusco, Cusco, Peru, Tel 51 910604344

Received: April 11, 2024 | Published: April 22, 2024

Citation: Rado C, Alarcón V, Ordoñez C, et al. Spermatic reserves in three South American camelids. J Dairy Vet Anim Res. 2024;13(1):27‒29. DOI: 10.15406/jdvar.2024.13.00343

Spermatic reserves were determined in three South American camelids: alpaca, llama, and vicuna. Reserves were determined at three different times: before the breeding season (November), after the breeding season (March and April), and during sexual rest (September). Three sexual organs: testicles, epididymis, and vas deferens were isolated from 12 alpacas, eight llamas, and a vicuna. Organs were weighed, and spermatozoa were collected into warmed tubes containing phosphate saline solution. Spermatic concentration was determined using the hemocytometer method. Data were analyzed using analysis of variance, and the Duncan test was used to assess differences, if any. There was a difference (P<0.05) in spermatic concentration and reserves between llama (41, 98), alpaca (15, 27), and vicuna (0.4 million spz/organ, and 1.4 million spz/g tissue, respectively. Likewise, in alpacas, there was a difference (P<0.05) in spermatic concentration and reserves by organs, being (47, 118 in the epididymis tail and 29 25 million for the vas deferens, respectively. Llama reproductive organs hosted more spermatozoa than alpaca and vicuna. The alpaca's spermatic reserves were not affected by the time of year. However, the epididymis tail and vas deferens contained more spermatozoa than any other reproductive organ.

Keywords: Spermatic reserves, Breeding, Llama, Alpaca, Vicuna

Reproductive management of the domesticated male South American camelid has two well-defined times. A period of intense sexual activity during the breeding season, for about two months, occurs during the summer months in South America. A second period of sexual rest for about nine months wherein males live far away from females (San Martin, 1968). By contrast, in the vicuna, breeding males live throughout the year with a group of females; however, males breed females during the summer months.1 During the spring season, November and December, transition months before breeding, males show sexual interest between them, with some males chasing others and attempting to mate. During the breeding period, January through March, males are joined to females and show intense sexual activity, with some males breeding more than four females daily. Following the breeding period, males are separated from females and maintained far away from them, which should be considered a time of sexual rest. These times of sexual activity and rest are repeated every year without any knowledge of the spermatic reserves, and they are still unknown today. Similar reproduction management is reported in dromedary camels.2

The objectives of the present study were to determine the spermatic reserves of three South American camelids, alpaca, llama, and vicuna, considering sexual activity and rest. Spermatic concentration was determined in three reproductive organs: testicles, epididymis, and vas deferens.

This study was conducted at the La Raya research center in the Southern hemisphere at 15° South latitude, 70° West longitude, and 4200 m above sea level.

Animals: Llamas and alpacas were randomly selected from a 150 herd of breeding males. Adult male alpacas, 12, were divided into three groups of 4 each: four before the breeding period, four after the breeding period, and four at the time of sexual rest. Male llamas, 3, were used after the breeding period. There were no llamas in the other two periods because of availability at the research station. All males were of reproductive age, 6 to 7 years old. They were maintained grazing on natural pastures. The adult vicuna used in this study was found dead in five vicunas kept close to the research center. The ethics committee of the research station and the University of San Antonio Abad approved all handling of animals.

Procedure: Males were euthanized following the research center's protocol before the breeding season (November), after the breeding season (March, April), and during the sexual rest (September). Three llamas were euthanized after the breeding season.

Reproductive organs: testicles, epididymis head, epididymis body, epididymis tail, and vas deferens were isolated, weighed, and separated in warmed phosphate saline solution. Spermatic concentration was determined by the hemocytometer method and expressed in millions of spermatozoa by organ. Sperm morphology was assessed in smears stained with Diff Quick stain and expressed as a percentage per tissue. Reserves were calculated by dividing the concentration by the weight of the organ.

Data were analyzed by variance analysis under the general linear method procedure using the NCSS statistical software, Layton, UT, USA. Statistical significance (P<0.05), if any, was calculated by the Duncan method.

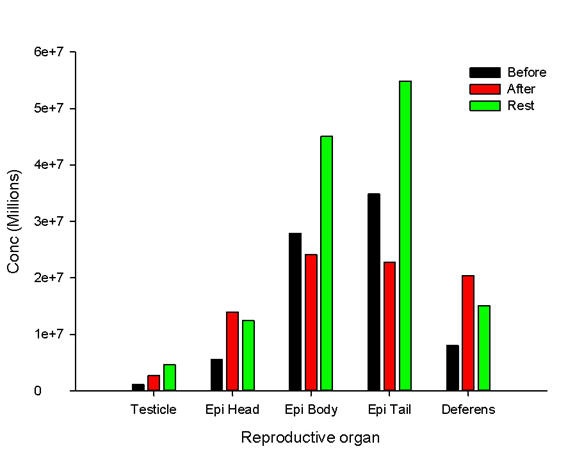

Spermatic concentration: There was no difference (P>0.05) in spermatic concentration between the left and right side in all reproductive organs; however, there was a difference (P<0.05) between reproductive organs and during the three reproductive states of the alpaca, (Figure 1). More spermatozoa (P<0.05) were determined in the epididymis tail than in any reproductive organ and the three periods considered in this study. The lower concentration (P<0.05) was found after breeding in all reproductive organs and the three study periods.

Figure 1 Spermatic concentration (millions of spermatozoa) in different reproductive organs and at three periods of the male alpaca.

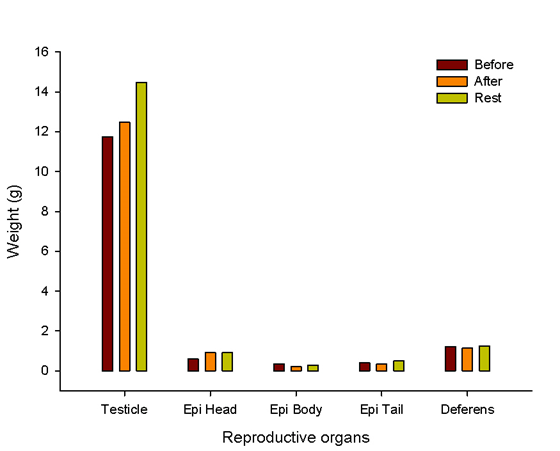

Weight of alpaca reproductive organs: There was a difference (P<0.05) in the weight of testicles (14.5 g), epididymis head (0.8 g), epididymis body (0.3 g), epididymis tail (0.4 g), and vas deferens (1.2 g) during reproductive stages (Figure 2). This difference was not apparent (P>0.05) by period.

Figure 2 Weight (g) of three different reproductive organs of the male alpaca under three observation periods, before and after breeding periods, and at the time of sexual rest.

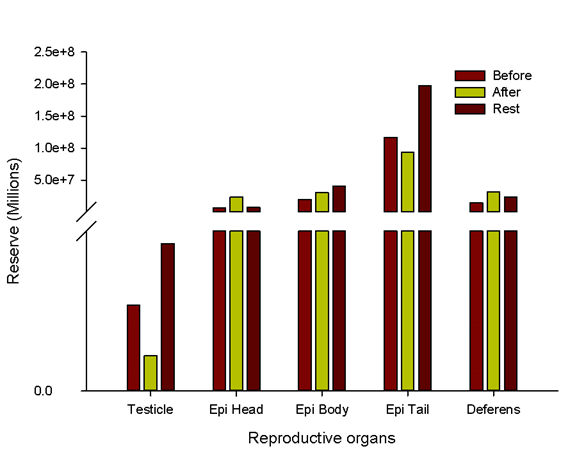

Spermatic reserves: There was a difference (P<0.05) in reproductive organs' spermatic reserves (Figure 3). There was no difference (P>0.05) in spermatic reserves by the time of the sexual period.

Figure 3 Spermatic reserves (millions of spermatozoa/g organ) in the male alpaca before, after the breeding period, and during sexual rest.

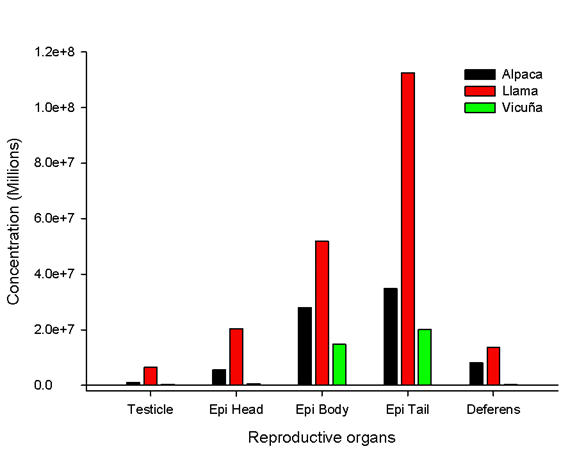

Spermatic concentration by species: There was a difference (P<0.05) in spermatic concentration and concentration by reproductive organs between llama, alpaca, and vicuna (Figure 4-6).

Figure 4 Spermatic concentrations (millions of spermatozoa) in different reproductive organs of male llamas, alpacas, and vicunas.

Reproductive organs by species: There were differences (P<0.05) in the weight of reproductive organs between llama, alpaca, and vicuna, Figure 5.

Spermatic reserves in two domesticated South American camelids, a llama, an alpaca, and a non-domesticated vicuna, were determined in this study. Sperm reserves are essential in all males and even more pronounced in species that must breed many females quickly. This is the case with llamas and alpacas; breeding occurs in two months, and males must breed at least 30 to 40 females. In this study, the reproductive organs, testicles, epididymis, and vas deferens were used. In the case of alpacas, reproductive organs were available before, after breeding periods, and during sexual rest. The order of reproductive organs that store more spermatozoa were the epididymis tail, epididymis body, and epididymis head (Figure 1) regardless of the reproductive period. Then, the vas deferens and, finally, the testicle. This is also the case for rams,3 goats,4 and bulls.5

Spermatic reserves in the reproductive periods of the alpaca demonstrated that reproductive organs accumulate spermatozoa before the breeding season in all of them. This is natural, considering male alpacas have a sexual rest of about ten months. Similar results have been reported in bulls6 and rams.7 There is no difference (P>0.05) in the concentration between the left and right sides among all reproductive organs. However, there was a difference (P<0.05) between the three study periods. The minor concentration was after the breeding season because of the intense work that males breed many females. Even though males are used in alternate groups, they are still subjected to intense breeding lasting 2 - 3 months. In addition, alpaca spermatic concentration is lower than other livestock species. In rams,3,8 angora goats,4 and stallions,9 billions of spermatozoa per ejaculate are reported. This is unique to the alpaca, llama, and camels.2

Spermatic reserves of adult male alpacas decreased following a breeding period and increased during sexual rest. There were no significant changes in the weight of testicles, epididymis, or vas deferens before and after the breeding periods and sexual rest.

The authors thank the Centro Experimental La Raya and the Universidad Nacional de San Antonio Abad del Cusco for providing animals for this study.

The authors do not have any conflict of interest.

©2024 Rado, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.