Journal of

eISSN: 2377-4312

Literature Review Volume 8 Issue 3

Correspondence: Trevor Wilson R, Bartridge Partners, Bartridge House, Umberleigh, North Devon EX37 9AS, UK

Received: May 07, 2019 | Published: May 15, 2019

Citation: Trevor WR. Directors of veterinary services in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan: William (Bill) Kennedy, 9 September 1924-September 1934. J Dairy Vet Anim Res. 2019;8(3):115-122. DOI: 10.15406/jdvar.2019.08.00253

William Kennedy was born in Scotland in 1884 and was elected a Member of the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons (MRCVS) in 1908. Working in British East Africa (now largely Kenya) in the years before the First World War (!914-1918) as a Veterinary Officer he was in part responsible for ensuring the health of livestock moving from the northern Masai areas to a southern reserve and preventing disease being transmitted to the herds of white settlers. Kennedy served in the East African Veterinary Corps as a Major throughout the war, was on the Staff of the Commander in Chief when Britain was fighting the armed forces of German East Africa and where his main concern was to ensure the health of the large number of riding and transport animals. He was three times Mentioned in Despatches and awarded the Distinguished Service Order. After the war he was successively acting and then Chief Veterinary Officer of the Kenya Colony and Protectorate, issuing numerous proclamations designed to control rinderpest, contagious bovine pleuro-pneumonia and foot and mouth disease. Leaving Kenya in 1924 he was appointed Director of Veterinary Services in Sudan, the first civilian to occupy the position. He served in Sudan until 1934 during a period when disease identification, diagnosis and control made great progress. Honoured with the award of the Order of the Nile Third Class by the King of Egypt, he retired to England and died there aged 80 in 1965.

Keywords: East African veterinary corps, First World War, Kenya, German East Africa, animal diseases

A charismatic religious leader claiming to be the Mahdi (“Guided One”) led an uprising against Egyptian rule (or more accurately misrule) in the 1880s. He died in 188 and was succeeded by the Khalifa (“Successor”). Victory over the Egyptian occupiers resulted in Sudanese control of the country. A British expeditionary force attempted to rescue the British General Gordon who had been sent by the United Kingdom to rally the country but he was killed and Khartoum was captured. Some 12years later a decisive victory by British military forces with some support from Egypt at the Battle of Omdurman on 3 September 1898 resulted in the reconquest of the country. A joint government by Egypt and Britain came into being as a Condominium known as the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan.1,2 Law and order was administered to some extent by a large military presence. Enormous numbers of cavalry and transport animals (horses, mules, donkeys and camels) were required to govern and control the turbulent population. A fledgling veterinary service was established to ensure the health of these animals. (Sudan was the seventh of all tropical countries to establish a veterinary service and the fourth in Africa after Zimbabwe (1890), Lesotho (1896) and Kenya (1897)).3 In all, 12 people served as Principal Veterinary Officers (to 1910) or as Directors of Veterinary Services (1910-1956) in the 55-year being of the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan before independence as the Republic of Sudan on 1 January 1956. During the early years the small number of veterinarians were military officers who were seconded, usually for short periods, from the British to the Egyptian Army which in turn employed them directly or seconded them to the Sudan. The first seven heads of veterinary services were all British military personnel but in the early 1920s the British War Office decided it would no longer maintain this arrangement. As a result William Kennedy, formerly a Major in the East African Veterinary Corps, was appointed as the first civilian director in 1924 and as the eighth director.

William Kennedy was born in Whiting Bay, Isle of Arran at 6a.m. in the morning of 18 February 1884, the third son of David Kennedy, a Hotel Keeper, and his young wife Margaret, formerly Taylor.4 William’s parents had married in the Gorbals in Glasgow on 18 November 1879. At the census of 1891 Willie Kennedy was aged 7, described as a Scholar, and the third of four boys in the household of his parents ay the Whiting Bay Hotel on the Isle of Arran in the River Clyde downstream from Glasgow. These parents were David Kennedy, Hotel Keeper and Farmer aged 55 and Maggie Kennedy aged 33. The brothers were Daniel aged 10, David aged 9 and Alexander aged 3. One female domestic servant and one male farm servant completed the household.5 The next verified record of William Kennedy is following his graduation from the Royal Veterinary College, London and his admittance as a Member of the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons (MRCVS) on 17 July 1908.6

East Africa 1911(??)-1924

The British administration of what is now the Republic of Kenya undertook two major forced moves of the Masai in British East Africa in the first two decades of the 20th Century. These moves had various motivating factors. White settlers had lobbied strongly to obtain land on the traditional Rift Valley and Laikipia grazing areas of the Masai; the administration wished to corral, control and tax the Masai more effectively in the ,reduced area allocated to the Masai and, through taxation to produce more labourers; to prevent the Masai from continuing to wander between two reserves; to stop the spread of “native” stock disease to European farms and to acquire an area for white pastoralists that was reportedly free of East Coast Fever (ECF).7 It is not known when William (Bill) Kennedy arrived in British East Africa but he was a Veterinary Officer on the second forced move of the Masai from their northen areas to a southern reserve in 1912-1913. One of his first tasks was to supervise the quarantine of ponies that were imported from Somalia. Kennedy was one of two vets in 1913 whose main job was to ensure that Masai stock moving from the northern areas to the southern reserve, and having to cross white settler farms on the trek, were as free from disease as possible.

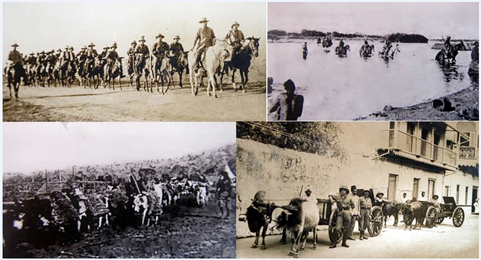

The main afflictions were contagious bovine pleuro pneumonia (CBPP) and rinderpest in 1904 to 1912. Blackquarter, ‘engamuni’ (ascribed by the Masai to "cattle rubbing against trees on which rhinoceros have scratched themselves") and ‘mbenek’ were noted in 1910 and redwater appeared in 1913. In a report of 21 April 1913 Kennedy wrote that ‘mbenek’ was “a Masai term applied to a disease resembling three day sickness or stiff sickness. This disease is seldom fatal, and several cases of it occurred during the move. That in my opinion, it is due to the cattle eating some poisonous weed or weeds”.8,1 In the same report Kennedy noted, with regard to the southern reserve, that rinderpest was prevalent there, mentioned his attention had been drawn to some bullocks which showed clinical symptoms of “'fly” (trypanosomosis) but blood slides that he had taken to confirm this had been broken in transit to Nairobi and rendered useless. He also quoted another person’s diagnosis of a sheep disease on Loita, termed by the Masai as “inginyot” (emaciation), as sheep pox. Kennedy made no additional comment and did not investigate further. The report referred to cases of anthrax in the reserve (from which many Masai died) but he also, investigated cases of pleuro-pneumonia in goats. Major William Kennedy was appointed Assistant Director of Veterinary Services of the British East Africa Protectorate dating from 26 October 2014.9 For the next four years he was occupied in fighting the enemy in German East Africa (now Tanzania). Although rinderpest was rampant there,10 Kennedy would be more concerned with the health of the many thousands of riding and transport animals used in multiple roles by the British (Figure 1).

Figure 1 The versatility of animals in the East African campaign. East African Mounted Rifles (Source: National Army Museum NAM. 2002-02-589-27); Indian Cavalry crossing a flooded river;16 Donkey supply train;18 Oxen pulling guns recovered from HMS Pegasus, sunk by German cruiser Königsburg and to be used as field guns (Source: National Army Museum NAM. 2002-02-589-23)

Kennedy appeared in the East African Veterinary Corps (EAVC) as a Major on 6 September 1914 but, on 10 February 1915, he was occupied otherwise than with his formal duties as he was inducted as a Freemason in the Progress Lodge in Nairobi.11 He soon left Nairobi to serve on the Staff of the Commander in Chief of the East African Force. This meant being with the armed forces in German East Africa (Tanzania) where his first Commander in Chief was Lieutenant General Smuts, one-time enemy of Britain in the Boer War of 1899-1902 but now fighting on the British side. Staff appointments usually meant being away from the fighting and operating from the rear but Smuts had been a Boer commander and his staff officers and quarters were mobile and close to the front. General Smuts had arrived in East Africa on 19 February 1916 but was already wiring despatches to the War Office in London only two months later on 16 April. In this early despatch, which related to fighting in the north of German East Africa around Kilimanjaro and Taveta, Temporary Major W Kennedy received a first Mention in Despatches,12 followed by a second mention seven months later13 when the action was along the central railway line and around Dar es Salaam and then a third mention by a new Commander in Chief in late 1917 when fighting had moved farther south in German Territory along the coast and around the Rufiji River14:

The accolade had, however, been conferred on Major Kennedy before his last Mention in Despatches when he was made a Companion of the Distinguished Service Order on 1 January 1918 in the King’s Birthday Honours15,2:

As soon as his arrival, or perhaps even earlier, General Smuts decided that mounted troops would play a leading role in his campaigns. This was in spite of the fact that much of the country was known to be infested with the tsetse fly with its fatal effects through its transmission of trypanosomosis most domestic animals but especially to equines. This was not just relevant to the mounted brigades but also to the overwhelmingly animal-powered supply system.16,17

There was, for example, high mortality in donkeys and porters in March 1917 as the army tried to maintain troops around Iringa. Dead mules, donkeys and carriers littered the road in various degrees of putrefaction. Animals died from exhaustion and thirst and from “horse sickness”.3 Buried carcasses were often dug up by porters for food and eventually they had to be burnt. In late April, a column left Duthumi for Tulo [in the now Mikumi National Park to the south of Morogoro in eastcentral Tanzania] but it was “doubtful if there could be a worse piece of road in the country or even in the whole of Africa. The distance is not more than 12 miles, but for nearly the whole way the road led through the worst sort of black stinking mud, it was throughout knee-deep in water, and sometimes the water was above the waist. To make matters worse, large numbers of cattle and donkeys had died in the swamp, and having rotted, the stink was too bad for words”. The donkeys were “wretched little beasts [that] seemed to be a failure in those parts owing to the tsetse fly, from the effects of which they die at the rate of about a hundred a week”. Donkeys partly obviated the need for porters but were very slow on the march and greatly increased the water needed by a body of troops and – in an ironic twist – porters occasionally had to be sent back to help the donkeys by carrying their loads.18

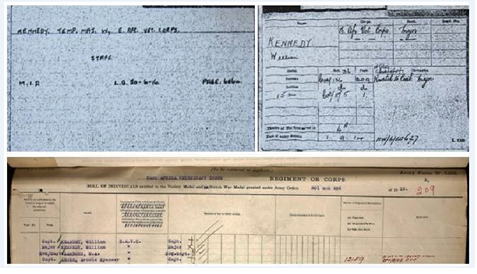

Major William Kennedy probably had a “good” war. By the time it ended in German East Africa he had obtained a DSO, had been Mentioned in Despatches three times and was later to be awarded the three campaign medals – the 1914-15 Star, the British War Medal and the Allied Victory Medal – that were usual for war service (Figure 2, Figure 3).12‒15,4 As a Staff officer, even in Smuts’ rather unconventional habit of having his Staff near the front line, it is likely that Kennedy had never actually been under the direct fire of the opposing force. The veterinary effort as a whole was also recognized in a despatch from the Commander in Chief of the East African Force in a despatch to the Secretary of State for War18a:

Figure 2 Army records of awards for William Kennedy. Medal index card for first Mention in Despatches (Source: British National Archives WO 372//24/35111); Medal index card for World War I Campaign Medals (Source: British National Archives WO 372/11/134923); Medal Roll for War and Victory Medals (Source: British National Archives WWI Service Medal and Award Rolls, 1914-1920).

Figure 3 Gallantry, campaign and honour awards of Major William Kennedy. Distinguished Service Order; 1914-15 Star; British War Medal; Allied Victory Medal with Oak Leaves Emblem for Mentions in Despatches; Order of the Nile, Third Class.

(Figure 2, Figure 3). On Kennedy’s return to the British East Africa Protectorate he resumed his position as Acting Chief Veterinary Office. He there found that livestock disease was rampant in the southern reserve to which the Masai had been largely confined. In January 1918 rinderpest had killed nearly all the calves in Narok District. There were "upwards of half a million deaths" in 1919-1920 from tick-borne diseases, CBPP and rinderpest. Two years later in 1922 between 60 and 100 per cent of all cattle in Narok and Loitokitok districts died from rinderpest. Kennedy went to Narok to discuss what could be done about controlling or confining CBPP. He concluded that inoculating the three quarters of a million or so Masai cattle in the reserve would require a staff of at least eight veterinary officers and 50 stock inspectors whereas he had only 12 vets and 11 stock inspectors in the whole Protectorate.19 Other than this his main occupation in the years to 1924 as Acting Chief Veterinary Officer (although he continued to sign himself on occasion as “Major” appears to have been to make “Proclamations” in the government’s official Gazette either imposing or rescinding restrictions on livestock movement.20:

Between 1920 and 1924, during which time the name of the country was changed from the East Africa Protectorate to the Colony and Protectorate of Kenya almost every issue of the official gazette contained several Proclamations with relevance to the Diseases of Animals Ordinance 1906. A random sample of gazettes reveals how widespread and serious was the livestock disease situation in the period. Four Proclamations in August 1920, for example, imposed quarantines for Rinderpest, CBPP and Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD) and revoked one for CBPP.21 In May 1921 there were two proclamations about Rinderpest and trypanosomiasis22 and a further six Proclamations in September regarding Rinderpest, CBPP and FMD.23 Later in 1921 the East Africa Protectorate became Kenya and the Kennedy became the substantive Chief Veterinary Officer. There were many problems in 1923 which was obviously a busy year for Kennedy and his staff with three Proclamations about Rinderpest and trypanosomiasis in January,24 further impositions and revocations in May,25 one imposition for East Coast Fever (ECF), one for Rinderpest and one revocation for ECF in October26 and two impositions for Rinderpest and FMD in November.27

Kennedy’s last Proclamations appeared in the Gazette in early May 1924 comprising a mixture of five impositions and revocations for Rinderpest and trypanosomiasis.28 Sometime before this, however, he had found time to marry a lady with the given names Jessie Wilson: as no marriage certificate has been found her surname is unknown but is possibly Macdonald. What we do know is that she was 10years his junior and was born on 9 September 1894. The SS Tanganjika of the Hamburg-Amerika Linie, in bound from Kilindini (Mombasa in Kenya), docked and was tied up at the quay at Southampton on 24 July 1924. On board having travelled First Class was William Kennedy aged 40 and a Veterinary Surgeon, Jessy Kennedy a wife, aged 30 and an infant Richard Kennedy under 12 months old, all residents of Kenya. Their intended destination was the Sports Club, 8 St James’ Square London SW1.29

Sudan September 1924-September 1934

Mr William Kennedy DSO arrived in Sudan on 10 December 1924 to take up his new appointment as the country’s Director of Veterinary Services (Table 1). He was the first civilian to be appointed to this position as well as being the first director to have had no previous experience of any kind in the country. Nor is it clear how well he got to know the country: all entries in the monthly or quarterly returns of Sudan Government senior personnel show him in Khartoum and never on tour.30 As for all other senior expatriate personnel Kennedy was provided with high quality living quarters and he and his family benefited from an annual home leave travelling in the luxury of the First Class accommodation on the world’s best ocean liners. The Sudan Veterinary Service was in a much healthier situation when William Kennedy took up the position of Director than it had been at the advent of some of his predecessors. In April 1924 there had been 13 British military vets on the establishment.31 The decision of the British War Office to cease the secondment of RAVC personnel to Sudan had not affected the numbers of personnel as some officers resigned their commissions but stayed on as pensionable civilian officials whereas others remained in the British Army but were seconded as Veterinary Inspectors to the newly formed Sudan Defence Force. Continuity of service was thus assured and the new Director now led a team of young men with the prospect of many years of useful and constructive work ahead of them.32,33 The so-called Research Section initiated in 1913 had done little other than routine diagnoses until the arrival of Captain R H Knowles as Veterinary Research Officer in 1922. He started to carry out proper research and his team was strengthened in 1925 by the arrival of S C J Bennett as Assistant Veterinary Research Officer.34 With the arrival of Bennett experimental work was much more thorough. Vaccines and prophylactic and curative measures against CBPP and Rinderpest reduced the mortality rate in some areas and were especially useful in allowing exports of cattle to Egypt to continue. Efforts were also made to control and cure camel trypanosomosis. A vaccine institute was established at Malakal as a counter measure to the import of vaccines. With limited staff and restricted mobility (the more widespread use of motor transport from 1928 improved this situation) it was not possible to control all the disease problems as many outbreaks were in the remote provinces of Kordofan and Darfur. Thus, although some success was achieved in areas where the Veterinary Department had access it could not be claimed that serum treatment had greatly reduced deaths in Darfur.35

Date |

Appointment |

Rank and name |

Location |

Notes |

10-Sep-24 |

Mr W. Kennedy DSO |

Arrived in Sudan |

||

01-Jul-25 |

Director |

Mr W. Kennedy DSO |

Khartoum |

Leave |

01-Jan-27 |

Director |

Mr W. Kennedy DSO |

||

01-Oct-27 |

Director |

Mr W. Kennedy DSO |

Khartoum |

|

01-Jan-28 |

Director |

Mr W. Kennedy DSO |

Khartoum |

|

01-Jul-28 |

Director |

Mr W. Kennedy DSO |

Khartoum |

Due from leave |

01-Jul-29 |

Director |

Mr W. Kennedy DSO |

Khartoum |

Due from leave 29 July |

01-Oct-29 |

Director |

Mr W. Kennedy DSO |

Khartoum |

|

01-Jul-30 |

Director |

Mr W. Kennedy DSO |

Khartoum |

For leave |

01-Oct-30 |

Director |

Mr W. Kennedy DSO |

Khartoum |

Due from leave 26 October |

01-Jan-31 |

Director |

Mr W. Kennedy DSO, M.R.C.V.S |

Khartoum |

|

01-Apr-31 |

Director |

Mr W. Kennedy DSO, MRCVS |

Khartoum |

|

01-Jul-31 |

Director |

Mr W. Kennedy DSO, MRCVS |

Khartoum |

For leave 21 July |

01-Jan-32 |

Director |

Mr W. Kennedy DSO, MRCVS |

Khartoum |

|

01-Apr-32 |

Director |

Mr W. Kennedy DSO, MRCVS |

Khartoum |

|

01-Jul-32 |

Director |

Mr W. Kennedy DSO, MRCVS |

Khartoum |

For leave 19 July |

01-Oct-32 |

Director |

Mr W. Kennedy DSO, MRCVS |

Khartoum |

Due from leave 24 October |

01-Jan-33 |

Director |

Mr W. Kennedy DSO, MRCVS |

Khartoum |

|

01-Apr-33 |

Director |

Mr W. Kennedy DSO, MRCVS |

Khartoum |

For leave 18 July |

01-Jul-33 |

Director |

Mr W. Kennedy DSO, MRCVS |

Khartoum |

For leave 23 July |

01-Oct-33 |

Director |

Mr W. Kennedy DSO, MRCVS |

Khartoum |

Due from leave 29 October |

01-Jan-34 |

Director |

Mr W. Kennedy DSO, MRCVS |

Khartoum |

|

01-Apr-34 |

Director |

Mr W. Kennedy DSO, MRCVS |

Khartoum |

For leave 24 June; retiring |

01-Jul-34 |

Director |

Mr W. Kennedy DSO, MRCVS, Nile 3rd Class |

Khartoum |

Due from leave 15 September; retiring |

Table 1 Outline of the career of William Kennedy in Sudan, 1924-1934.30

A horse improvement scheme had been set up in Darfur and Kordofan Provinces in 1926.36,37 The next year it was reported38:

Stallion numbers built up and by 1929 there were 25 standing in Darfur of which three were English thoroughbreds, one an Egyptian thoroughbred, 18 Arabs and three Sudan country breds. Unfortunately the early promise of the scheme was not fulfilled as it appeared that the later generations of progeny could not cope with the harsh environment and the management conditions of their nomadic owners.

Kennedy also wanted to improve the local cattle. In 1927 he considered39:

The global depression of the late 1920s and 1930s coincided with years of poor or moderate rains and difficult grazing conditions over most of the central Sudan. The worst epizootic of rinderpest for many years broke out in 1930 with over 15 000 deaths – nearly half in Kordofan Province -- reported. Most of the main cattle producing areas were affected until the epizootic was brought under control in 1932. Matters might have been much worse had it not been for three important factors: first, the cattle owners' confidence in the Department had increased and they were now regularly reporting disease occurrence; second, motor transport greatly appeased the burden on the Department from 1929; and, thirdly, local production of anti-rinderpest serum of small quantities of spleen-tissue vaccine proved beneficial. Although laboratory output never fully met the total demand sufficient serum was produced for reserves to be held at strategic points to ensure prompt action as fresh outbreaks were reported. Local authorities were also keen to have their own tribal staff and in 1929 the first tribal veterinary retainers had been trained and appointed and, as numbers grew, proved an invaluable addition to the field staff.32

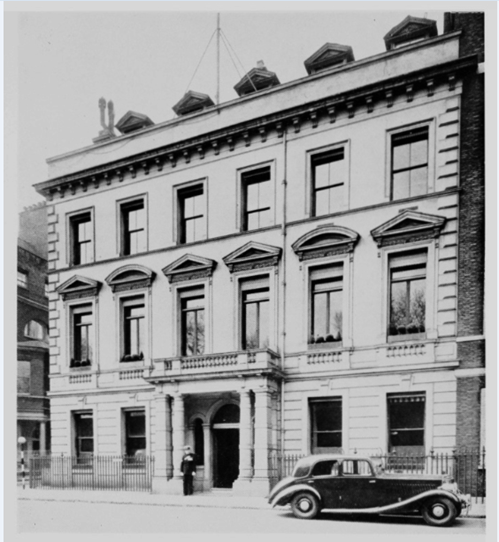

Regular home leave for Kennedy and his family continued. On 13 October 1933, William Kennedy, Veterinary Surgeon aged 49 with wife Jessie age 39 (but without children) whose home address was The Sports Club St James Square, London SW1 with permanent residence in Sudan, departed Liverpool bound for Port Sudan on board the MV Staffordshire of the Bibby Line.40 Kennedy, aged 50, Veterinary Surgeon, departed Port Sudan on final leave in late June 1934 and arrived London on 9 July on board MV Staffordshire with wife Jessie Wilson Kennedy, aged 40. Their home address was now 17 Earls Court Square, London SW5 (Figure 5).41

Figure 4 Number 8, St James’ Square, London: the premises of the Sports Club and the pied-à-terre of William Kennedy on arriving from leave or departing for duty in Kenya and Sudan.

Figure 5 Number 17 Earl’s Court Square, London: the home address of William and Jessie Kennedy in the early 1930s.

Kennedy probably returned to Sudan for a final time as Director to as Director Mr W Kennedy DSO MRCVS Nile 3rd class who was retiring was due back from leave on 15 September 1934. Shortly before this he received one of the perks of his job when he was awarded the Order of the Nile Third class by the King of Egypt42:

Later life 1934-1965

Little is known of Kennedy after his retirement. In November 1934, however, he was a petitioner in a court case, along with his eldest brother Daniel, who had followed in his father’s footsteps as a pub landlord as he was the licensee of the Castle Inn in Dundonald, This concerned a petition to have their youngest brother Alexander to be presumed dead. Alexander had been crew on a ship to the United states and then on another ship from Galveston in Texas bound for South America in 1926. Nothing having been heard since and seven ears having past the judge granted the petition. In this case Kennedy was described as working in the Veterinary Services, Sudan Government, Khartoum.43

Mr and Mrs Kennedy next appear in the Register for 1939. William Kennedy, born 18 February 1884, describes as Director Sudan Veterinary Services Retired and an ARP Warden plus Jessie Kennedy born 7 July 1894 (plus one record officially closed) were living in Swanage Road, Registration District EDNA, Gosport Municipal Borough.44 William Kennedy died in the Portsmouth area in the autumn of 1965 aged 80.45 His wife Jessie W Kennedy outlived him by almost three years before she died in the summer of 1968 aged 74.46

1Now known as ephemeral fever: outbreaks are usually associated with very heavy or prolonged rainfall.

2The Distinguished Service Order was initially awarded for individual acts of meritorious or distinguished service in war for service under fire or in conditions equivalent to service in actual combat with the enemy. It was usually awarded to officers of the rank of major or higher but there were many exceptions to this. A rule that the DSO could only be gained by a person who had already been mentioned in Despatches was rescinded in 1943. In World War I some DSOs were awarded under circumstances not under fire and often to Staff officers. It is probable that Kennedy’s award was a case of the latter and for the King’s Birthday and New Year’s Honours lists no individual citations were made.

3This was presumably trypanosomosis rather than African Horse Sickness. ‘Surra’, a disease of horses and camels due to Trypanoma evansi is not transmitted by tsetse but by biting flies of the family Tabanidae outside the tsetse belt: nowadays most Tanzanian horses (but not donkeys) are given regular prophylaxis against it.

4The 1914 Star was awarded only to personnel who had served in France or Belgium between the outbreak of war on 5 August 1914 and 22 November 1914. The 1914-15 star was awarded officers and men of British and Imperial forces who served against the Central European Powers in any theatre of the Great War between 5 August 1914 and 31 December 1915 provided they had not already received the 1914 Star. The Medals differed only in the central medallion inscription which was “1914" for the 1914 Star and “1914-15" for the 1914-15 Star.

None.

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

©2019 Trevor. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.